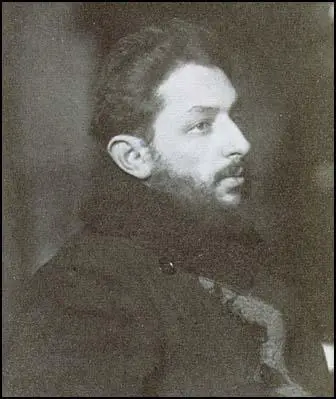

Eugen Levine

Eugen Levine, the son of wealthy Jewish parents, was born in St Petersberg, Russia, on 10th May 1883. His father, Julius Levine, was a self-made man who had amassed a large fortune. It was claimed that "Levine's mother, Rosalia, was a woman of great beauty and charm, intelligent and determined, the perfect hostess in an elegant and cultured home."

In 1886, when he was only three years old, his father died of smallpox. His mother arranged for him to be educated at an exclusive boarding school in Wiesbaden. Levine became interested in politics. At the age of fifteen he wrote: "I should like to serve the people... Not by sham but by genuine service, not by offering them crumbs like the councillors of Rome to gain the sympathy of the masses, but by sincere work for their welfare... I wish to denounce the enemies of the people from the council tribunals, to protect the oppressed and to help them to establish their rights... That is my aim. That is what I vow to fulfill."

Levine moved to Heidelberg where he came into contact with Russians living in exile. They were members of the Social Revololutionaries. The main policy of the SR was the confiscation of all land. This would then be distributed among the peasants according to need. The party was also in favour of the establishment of a democratically elected constituent assembly and a maximum 8-hour day for factory workers.

The SR, was influenced by the tactics used by the People's Will and had a terrorist wing, the SR Combat Organization. Membership of this group was secret and independent of the rest of the party. Gregory Gershuni, became its head and was responsible for planning the assassination of the Minister of the Interior, Dmitry Sipyagin. The following year he arranged the assassination of N. M. Bogdanovich, the Governor of Ufa. Gershuni was unaware that his deputy, Evno Azef, was in the pay of the Okhrana. In 1904 Azef secretly provided the secret police with the information needed to arrest and try Gershuni with terrorism.

As the author of Levine: The Life of a Revolutionary (1973) pointed out: "He (Levine) received his first revolutionary ideas from the Social Revolutionaries whose programme included acts of individual terror. They believed that by assassinating certain dignitaries of state, above all the Czar, they could shatter the foundation of the existing system and bring about socialism. This programme called for a great deal of individual gallantry and self-sacrifice. It was only too natural that the young and inexperienced Levine should be fascinated by its heroic aspects. To correct injustice, to give his life for the oppressed - had this not been his dream since childhood? He became an enthusiastic member of that party."

Levine returned to Russia to take part in the 1905 Revolution. He was arrested, imprisoned and exiled to Siberia where he worked in a lead mine. After escaping he wrote to his mother in 1906: "If you try again to persuade me to give up my way of life, my visit will be quite senseless. The result would only be bitterness and misunderstanding. Only if you are really reconciled to realities, if you have given up hope of changing me, could I come."

Levine now became a full-time agent of the Social Revololutionaries. He wrote to his sister: "I am now in Bryansk province Orlov, one of the most important economic centres. It has a strong organisation but I am the only intellectual. And since the factories are scattered between forests and swamps hundreds of miles apart, I am always on the move."

Levine eventually left Russia and studied at Heidelberg University. He joined the Social Democrat Party (SDP) and gave lectures on the 1905 Revolution. In 1914 he met Rosa Broido. She later recalled: "For me it was love at first sight." Rosa, the daughter of a rabbi, was born in Gródek, Poland, in 1890.

Fjodor Stepun, was a fellow student who met Levine during this period: "By his faith he was a humanitarian atheist; in his appearance a typical Jew, with an almost aristocratic long face, beautiful melancholy eyes, moving with a slightly protruded shoulder, resembling an Egyptian relief. During our friendship he was an uncommonly soft, even sentimental young man who wrote poems about the autumn rain drumming on the roofs of the workers. His socialism, not enlivened by any personal experience and devoid of any fanaticism and dogmatism, was clearly marked by ethical and pedagogical features."

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter."

Immediately after the vote on war credits in the Reichstag, a group of SDP anti-militarist activists, including Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Hugo Eberlein met at the home of Rosa Luxemburg to discuss future action. They agreed to campaign against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Levine became a supporter of this group.

In May 1915 Levine married Rosa Broido. Levine told her: "We have reached a degree of happiness which will never be surpassed". In a letter he wrote to Rosa: "Everything seems to attain sense and meaning. I wake up with you, I walk with you all day long, I lie down and my right arm waits for you with joy and tenderness... I thank you for making me young again, for teaching me to love so deeply, to glow and to love; and for loving me, for the gift of your tender, delicate-passionate love."

Soon after the wedding Levine was called up into the German Army and appointed as an interpreter in a camp for high-ranking allied prisoners of war, situated on the outskirts of Heidelberg. Rosa later recalled: "It was an easy assignment. He was allowed to live out and report for duty like any other civilian. Yet he soon came to hate his work. His obligations included the censorship of the incoming and outgoing letters, which made him an involuntary participant in the intimate life of the camp inmates. He felt like an intruder and when he had to deliver particularly sad or emotional letters could not look the recipient in the eye. They were class-enemies, military men who in a given situation would shoot him - or he them for the matter. But he always knew where to draw the line between revolutionary necessity and his innate humanitarian feelings, and never refused anybody help or sympathy in his private life."

Levine was eventually denounced as a security risk and was moved to other duties. Later he worked as an interpreter at war-prisoners' courts. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "The offences varied from petty thefts and disobedience to more serious, sexual assaults. The predominantly illiterate convicts were often not even able to state their case, and much skill was needed to unravel the actual proceedings." In 1916 Levine was invalided out of the German Army. He returned to Heidelberg University where he lectured on Russia.

Levine remained a member of the undercover Spartacus League. On 1st May, 1916, the group decided to come out into the open and organized a demonstration against the First World War in the Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. One of those who attended reported: "It was a great success. At eight o'clock in the morning a dense throng of workers - almost ten thousand - assembled in the square, which the police had already occupied well ahead of time. Karl Liebknecht, in uniform, and Rosa Luxemburg were in the midst of the demonstrators and greeted with cheers from all sides." Several of its leaders, including Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were arrested and imprisoned.

After the Russian Revolution, Levine became the Russian Ambassador's adviser on German affairs in the Embassy in Berlin. Rosa was also employed as a Russian-German interpreter. Levine remained a member of the Social Revololutionaries until it staged a putsch to reverse the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. Levine now joined the Bolsheviks.

In 1918 Levine joined ROSTA, the Soviet News Agency, as head of its Russian section. Rosa became his private secretary. She later recalled: "This was the start of my political awakening. My job consisted in correcting the Russian translations. I had to deal with matters which I had to deal with matters which had never interested me before and to absorb daily a great deal of knowledge of what was going on around me." He also went on speaking tours

Karl Liebknecht was released from prison in October, 1918, when Max von Baden granted an amnesty to all political prisoners. Rosa commented: "In those faraway days the Soviet Embassy was not afraid openly to associate itself with Communists. Liebknecht's release from prison was celebrated with a lavish reception and Levine and I were among the guests. The occasion was also memorable for food and drink and healthy, uncrippled men - another rarity in the last year of the war."

Levine also went on speaking tours in support of the Spartacus League. According to Rosa Levine: "His first propaganda tour through the Ruhr and Rhineland was crowned with almost legendary success... They did not come to get acquainted with Communist ideas. At best they were driven by curiosity, or a certain restlessness characteristic of the time of revolutionary upheavels... Levine was regularly received with catcalls and outbursts of abuse but he never failed to calm the storm. He told me jokingly that he often had to play the part of a lion-tamer."

Karl Radek, a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee, argued that the the Soviet government should help the spread of world revolution. At the end of the First World War Radek was sent to Germany and with a group of radicals who had been members of the Spartacus League, including Eugene Levine, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Max Levien, Eugen Levine, Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring and Clara Zetkin, helped to establish the German Communist Party (KPD) in December, 1918.

In Germany elections were held for a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution for the new Germany. As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League."

As Rosa Levine pointed out: "It had the advantage of bringing the Spartacists closer to the broader masses and acquainting them with Communist ideas. Nor could a set-back, followed by a period of illegality, even if only temporary, be altogether ruled out. A seat in the Parliament would then be the only means of conducting Communist propaganda openly.It could also be foreseen that the workers at large would not understand the idea of a boycott and would not be persuaded to stay aloof; they would only be forced to vote for other parties."

On 9th November, 1918, Emil Eichhorn was appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces."

At a convention of the Spartacus League, on 1st January, 1919, Luxemburg was outvoted on the issue of elections. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising. Almost alone in her party, Rosa Luxemburg decided with a heavy heart to lend her energy and her name to their effort."

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other."

Members of the Independent Socialist Party and the German Communist Party jointly called for a protest demonstration. They were joined by members of the Social Democratic Party who were outraged by the decision of their government to remove a trusted socialist. Eichhorn remained at his post under the protection of armed workers who took up quarters in the building. A leaflet was distributed which spelt out what was at stake: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers. The blow which is aimed at the Berlin police chief will affect the whole German proletariat and the revolution."

One of the organisers of the protests, Paul Levi, argued: "The members of the leadership were unanimous: a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat. None of these slogans implied an overthrow of the government."

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck on 16th January. Paul Frölich, the author of Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940) has explained what happened next: "A short while after Liebknecht had been taken away, Rosa Luxemburg was led out of the hotel by a First Lieutenant Vogel. Awaiting her before the door was Runge, who had received an order from First Lieutenants Vogel and Pflugk-Hartung to strike her to the ground. With two blows of his rifle-butt he smashed her skull. Her almost lifeless body was flung into a waiting car, and several officers jumped in. One of them struck Rosa on the head with a revolver-butt, and First Lieutenant Vogel finished her off with a shot in the head. The corpse was then driven to the Tiergarten and, on Vogel's orders, thrown from the Liechtenstein Bridge into the Landwehr Canal, where it was not washed up until 31 May 1919."

Paul Frölich, the author of Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940) has explained what happened: "A short while after Liebknecht had been taken away, Rosa Luxemburg was led out of the hotel by a First Lieutenant Vogel. Awaiting her before the door was Runge, who had received an order from First Lieutenants Vogel and Pflugk-Hartung to strike her to the ground. With two blows of his rifle-butt he smashed her skull. Her almost lifeless body was flung into a waiting car, and several officers jumped in. One of them struck Rosa on the head with a revolver-butt, and First Lieutenant Vogel finished her off with a shot in the head. The corpse was then driven to the Tiergarten and, on Vogel's orders, thrown from the Liechtenstein Bridge into the Landwehr Canal, where it was not washed up until 31 May 1919."

Emil Eichhorn later commented: "The Berlin proletariat was sacrificed to the carefully calculated and artfully executed provocation of the government of the day. The government sought the opportunity to deal the revolution its death blow... Although to some extent armed, the proletariat was in no way equipped for serious fighting; it fell into the trap of the pacification negotiations and allowed its strength, time and revolutionary fervour to be destroyed. In the meantime, the government, having at its disposal all the resources of the state, could prepare for its final subjugation."

Eugen Levine went into hiding. Under the assumed name of Berg, he worked for the German Communist Party in the Ruhr. He then attempted to travel to Moscow with Hugo Eberlein. Eugen's wife commented: "The very German Eberlein, blonde, blue-eyed, handsome, highly intelligent, had his own way of dealing with the problem. He demonstrated it to us by pulling a face so harmless and dull as to put off the most experienced investigator. Levine's appearance was less fit for an illegal journey. He was duly picked out in Kovno, the border town, and was ordered to leave the train for further investigation." Levine managed to escape and returned to Berlin.

Left-wing socialists remained in control in Bavaria, where Kurt Eisner formed a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party. During this period the living conditions of the Munich workers and soldiers were rapidly deteriorating. It was not a surprise when at the election on 12th January, 1919, in Bavaria, Eisner and the Independent Socialist Party received only 2.5 per cent of the total vote. Eisner remained in power by granting concessions to the SDP. This included agreeing to the establishment of a regular security force to maintain order. As Chris Harman pointed out: "In office without any power base of his own, he was forced to behave in an increasingly arbitrary and apparently irrational manner".

On 21st February, 1919, Kurt Eisner decided to resign. On his way to parliament he was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria.

One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city. Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rose Levine argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency."

Levine received instructions to go to Munich to take control of the situation. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganising the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control.

Eugen Levine pointed out that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed.

Inspired by the events of the October Revolution, Levine ordered the expropriated of luxury flats and gave them to the homeless. Factories were to be run by joint councils of workers and owners and workers' control of industry and plans were made to abolish paper money. Levine, like the Bolsheviks had done in Russia, established Red Guard units to defend the revolution. He also argued that: "We must speed up the building of revolutionary workers' organisations... We must create workers' councils out of the factory committees and the vast army of the unemployed."

Johannes Hoffmann and other leaders of the Social Democratic Party in Munich fled to the town of Bamberg. Hoffman blocked food supplies to the city and began looking for troops to attack the Bavarian Soviet Republic. By the end of the week he had gathered 8,000 armed men. On 20th April Hoffmann's forces clashed with troops led by Ernst Toller at Dachau in Upper Bavaria. After a brief battle, Hoffmann's army was forced to retreat.

Sebastian Haffner wrote in his book, Failure of a Revolution: Germany, 1918-19 (1973), that Levine was the communists best hope for leading the revolution: "Eugen Levine, a young man of impulsive and wild energy who, unlike Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, probably possessed the qualities of a German Lenin or Trotsky."

Levine announced that the German Communist Party had doubts about the proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, but that the party would be in "the forefront of the fight" against any counter-revolutionary attempt and urged the workers to elect "revolutionary shop stewards" in order to defend the revolution. Levine argued that they should "elect men consumed with the fire of revolution, filled with energy and pugnacity, capable of rapid decision-making, while at the same time possessed of a clear view of the real power relations, thus able to choose soberly and cautiously the moment for action."

Francis Ludwig Carsten, the author of Revolution in Central Europe: 1918-1919 (1972), has argued: "From 14 to 22 April there was a general strike, with the workers in the factories ready for any alarm. The Communists sent their feeble forces to the most important points... The administration of the city was carried on by the factory councils. The banks were blocked, each withdrawal being carefully controlled. Socialisation was not only decreed, but carried through from below in the enterprises."

Some of the revolutionaries realised that it was not possible to create a successful Bavarian Soviet Republic. Paul Frölich argued: "Bavaria is not economically self-sufficient. Its industries are extremely backward and the predominant agrarian population, while a factor in favour of the counter-revolution, cannot at all be viewed as pro-revolutionary. A Soviet Republic without areas of large scale industry and coalfields is impossible in Germany. Moreover the Bavarian proletariat is only in a few giant industrial plants genuinely disposed towards revolution and unhampered by petty bourgeois traditions, illusions and weaknesses."

Johannes Hoffmann now arranged for a new propaganda campaign to take place in Bavaria. All over the region posters appeared saying: "The Russian terror rages in Munich unleashed by alien elements. This shame must not endure for another day, another hour... Men of the Bavarian mountains, plateaux and woods, rise like one man... Head for the recruiting depots. Signed Johannes Hoffman."

Rosa Levine argued: "The streets were filled with workers, armed and unarmed, who marched by in detachments or stood reading the proclamations. Lorries loaded with armed workers raced through the town, often greeted with jubilant cheers. The bourgeoisie had disappeared completely; the trams were not running. All cars had been confiscated and were being used exclusively for official purposes. Thus every car that whirled past became a symbol, reminding people of the great changes. Aeroplanes appeared over the town and thousands of leaflets fluttered through the air in which the Hoffmann government pictured the horrors of Bolshevik rule and praised the democratic government who would bring peace, order and bread."

On 26th April, Ernst Toller made an attack on the leaders of the German Communist Party in Munich that had established the Second Bavarian Soviet Republic. "I consider the present government a disaster for the Bavarian toiling masses. To support them would in my view compromise the revolution and the Soviet Republic."

The Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, has argued: "Levine, a lucid, sceptical, efficient professional of revolution among noble amateurs living out the dream of liberation and confused militants, knew that it was lost, but also that it had to fight. Though not lacking in at least passive support among the Munich workers, the Soviet Republic horrified the conservative and Catholic peasantry and the notably reactionary middle class of Bavaria to the point where they welcomed the joint invasion of government troops and Free Corps from all over Germany (including a Bavarian Free Corps)."

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, eventually arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly."

Levine pointed out that Colonel Franz Epp posed a serious threat to the revolution: "Colonel Epp is already recruiting volunteers. Students and other bourgeois youths are flocking to him from all sides. Nuremberg declared war on Munich. The gentlemen in Weimar recognise only Hoffmann's government. Noske is already whetting his butcher's knife, eager to rescue his threatened party friends and the threatened capitalists."

With Ebert's troops massing on Bavaria's northern borders, the Red Guards began arresting people they considered to be hostile to the new regime. On 29th April, 1919, eight men were executed after being found guilty of being right-wing spies. Rosa Levine, the author of Levine: The Life of a Revolutionary (1973) wrote: "It was never established who ordered the shooting. None of the Communist leaders were at that time in the building. Levine for one left it long in advance of the deplorable act." Ten members of the Thule Society, the anti-Semitic precursor of Nazism, were also murdered.

The Freikorps entered Munich on 1st May, 1919. Over the next two days the Freikorps easily defeated the Red Guards. Gustav Landauer was one of the leaders who was captured during the first day of fighting. Rudolf Rocker explained what happened next: "Close friends had urged him to escape a few days earlier. Then it would have still been a fairly easy thing to do. But Landauer decided to stay. Together with other prisoners he was loaded on a truck and taken to the jail in Starnberg. From there he and some others were driven to Stadelheim a day later. On the way he was horribly mistreated by dehumanized military pawns on the orders of their superiors. One of them, Freiherr von Gagern, hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim.... He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer - one of Germany's greatest spirits and finest men."

Allan Mitchell, the author of Revolution in Bavaria (1965), pointed out: "Resistance was quickly and ruthlessly broken. Men found carrying guns were shot without trial and often without question. The irresponsible brutality of the Freikorps continued sporadically over the next few days as political prisoners were taken, beaten and sometimes executed." An estimated 700 men and women were captured and executed."

Levine went into hiding. On 12th May he wrote to Rosa Levine: "At last I can send you a few words, my love, my dear. You were all the time beside me and my heart rejoiced when I thought of the last period of our life. During all those desperate hours, hours of terror, I was full of those memories. I recalled our talks, your words, your kisses and caresses. Don't be sad Oslishechko. I am cheerful and full of energy. In spite of all the distress, I am looking to the future with confidence. As to us, I firmly hope that we shall be together very soon. And together with the child before my departure."

Later that day Levine was arrested by the authorities. Levine's cell was left open in the hope that he would be beaten to death. According to his wife: "Soldiers were constantly patrolling the corridors, entering his cell and keeping him in a state of great suspense." A warder told his wife that "we were told that your husband ordered the execution of 10,000 prison warders and policeman."

In court Levine defended his actions: "The Proletarian Revolution has no need of terror for its aims; it detests and abhors murder. It has no need of these means of struggle, for it fights not individuals but institutions. How then does the struggle arise? Why, having gained power, do we build a Red Army? Because history teaches us that every privileged class has hitherto defended itself by force when its privileges have been endangered. And because we know this; because we do not live in cloud-cuckoo-land; because we cannot believe that conditions in Bavaria are different - that the Bavarian bourgeoisie and the capitalists would allow themselves to be expropriated without a struggle - we were compelled to arm the workers to defend ourselves against the onslaught of the dispossessed capitalists."

Levine accepted that the court would order his execution: "We Communists are all dead men on leave. Of this I am fully aware. I do not know if you will extend my leave or whether I shall have to join Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In any case I await your verdict with composure and inner serenity. For I know that, whatever your verdict, events cannot be stopped... Pronounce your verdict if you deem it proper. I have only striven to foil your attempt to stain my political activity, the name of the Soviet Republic with which I feel myself so closely bound up, and the good name of the workers of Munich. They - and I together with them - we have all of us tried to the best of our knowledge and conscience to do our duty towards the International, the Communist World Revolution."

The Münchener Post reported: "Levine faced the Court on the second day of the trial with an indifference to the fate hanging over him which alone could shatter the indictment of cowardice by the Public Prosecutor. The unstudied posture of the defendant undoubtedly impressed many of those who had not experienced the Levine of the second Soviet Republic. Levine relieved his Counsel of the task of defending him. In his final speech, which put into the shade all the rhetoric of his professional advocates, he resolutely swept aside all the little tricks which his Counsel brought forward in his favour. Lucid, calm and to the point the speech was more effective than all that had been said in his defence during the long preceding hours. Once again it became evident that he possessed courage wrongfully denied to him, that he skilfully remained master of the situation, that he succeeded with a superiority of his own, in crystallising all those points which ensured him his influence on the masses."

In court Levine was defended by Count Pestalozza, a member of the Catholic Centre Party. He argued: "Don't send this man to his death, for should you do so, he would not die, he would start to live again. The life of this man would lie on the conscience of the entire community and his ideas would generate the seed of terrible revenge."

Levine was sentenced to death on 3rd June, 1919. Soon afterwards he had his last meeting with Rosa Levine. He told her: "It will soon be over. It is you who will suffer more. But don't forget: you must not live a joyless life. You must think of our boy. He must not be burdened with an unhappy mother."

The Frankfurter Zeitung wrote that it was the duty of the Social Democrat Party government to prevent the execution "by every means, even at the risk of evoking a cabinet crisis." The Neue Zeitung, which denounced Levine as "the seducer of the Munich proletariat" called for him to be reprieved: "Wide circles, from the government down to the non-socialist community, left no doubt that under the prevailing political conditions, which were the background of Levine's crimes, the application of mercy and political wisdom would be more more appropriate than punishment. Both socialist parties, usually at loggerheads, agreed that this was a case which simply cried out for a reprieve."

Eugen Levine was shot by firing squad in Stadelheim Prison on 5th July, 1919.

Primary Sources

(1) Rosa Levine-Meyer, Levine: The Life of a Revolutionary (1973)

It was in Heidelberg, in 1903, at the age of twenty, that Levine for the first time in his life came into contact with Russian intellectuals, and became acquainted with revolutionary ideas. They found a powerful response in his restless mind, and no distractions or attempts at reconciliation with his society were ever able to stifle them.

He received his first revolutionary ideas from the Social Revolutionaries whose programme included acts of individual terror. They believed that by assassinating certain dignitaries of state, above all the Czar, they could shatter the foundation of the existing system and bring about socialism. This programme called for a great deal of individual gallantry and self-sacrifice. It was only too natural that the young and inexperienced Levine should be fascinated by its heroic aspects. To correct injustice, to give his life for the oppressed - had this not been his dream since childhood? He became an enthusiastic member of that party.

(2) Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution (1982)

On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralysed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind.

(3) Eugen Levine, speech (4th April, 1919)

I have just learned of your plans. We Communists harbour profound suspicion of a soviet republic initiated by the Social Democrat minister Schneppenhorst and men like Durr, who up to now have combated the soviet system with all their power. At best we can interpret their attitude as the attempt of bankrupt leaders to ingratiate themselves with the masses by seemingly revolutionary action, or worse, as a deliberate provocation.

We know from our experience in northern Germany that the Social Democrats often attempted to provoke premature actions which are the easiest to crush.

A soviet republic cannot be proclaimed at a conference table. It is founded after a struggle by a victorious proletariat. The proletariat of Munich has not yet entered the struggle for power.

After the first intoxication the Social Democrats will seize upon the first pretext to withdraw and thus deliberately betray the workers. The Independents will collaborate, then falter, then begin to waver, to negotiate with the enemy and turn unwittingly into traitors. And we as Communists will have to pay for your undertaking with blood?

(4) Eugen Levine, letter to Rose Levine (April 1919)

The workers, the best of them, will fight whatever our instructions. A revolutionary is no less ready to give his life in upholding the honour of his cause than the patriot who fights to the last ditch preferring death to surrender. The workers would only despise a leader who fell below their own standards of revolutionary honour and preached, in advance, the laying down of arms. It might seem irrational but then no great achievements were ever accomplished without this spirit.

The White Army will, in any case, find a pretext for a bloodbath. They need this, and the extent of the slaughter will be determined by political calculations alone, by nothing else. Is workers' blood so cheap as to let it flow unopposed for the satisfaction of newly converted pacifists?

I know it is difficult to accept this hard truth. Toller's protestations of his abhorrence of bloodshed are much more appealing. Yet during the war our roles were reversed: The party of the soft-hearted Independents was not afraid of bloodshed and supported the capitalist government in the alleged "defensive war," and we were in the front lines of the fight against such carnage. It all depends on your aims and on where you stand. Could there be a more clear-cut defensive war than the one which is forced upon us? No one would be happier than the bloodthirsty Communists if the Independents could persuade the White Army to abstain from fighting. We don't want the fight, nor do we need it.

Are you convinced? Hard days lie ahead. We must at least be able to feel that they could not be averted.

(5) Eric Hobsbawm, The German Revolution (1973)

In Bavaria, hardly a stronghold of the labour movement, the revolution under the leadership of the Independent Social Democrat Kurt Eisner and a peasant leader, each representing quite small organisations, had demonstrated what it might have achieved in Germany. Eisner became prime minister of a Bavarian Republic, supported by all sections of the left, and attempted a sort of combination of a democratic constitution with a republic of the councils. This left-wing regime survived the collapse of the revolution in Berlin and most other parts of the country, but Eisner was assassinated in February 1919 by an ultra-reactionary, Count Arco. To this part of Germany the Communist Party sent Eugen Levine. Here he participated in, and attempted to introduce some element of serious organisation and effectiveness into, the Bavarian Soviet Republic of April 1919.

It is possible, though perhaps not very likely, that Bavaria could have maintained itself as an autonomous and relatively left-wing regime, based on the unity of its labour movement and the proverbial dislike of Bavarians for going the way of the rest of Germany. At all events Berlin hesitated to intervene against it. But a Soviet Republic was doomed. Levine himself was opposed to it. After the proclamation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 21, 1919, however a wave of utopian hope swept across the Bavarian movement. If they gave another signal, would not Austria also rise and a central European soviet zone come into existence? A Soviet Republic was proclaimed in Munich and enthusiastically joined by the numerous, often anarchist and semi-anarchist writers and intellectuals of what was Germany's most celebrated Latin Quarter. Levine, a lucid, sceptical, efficient professional of revolution among noble amateurs living out the dream of liberation and confused militants, knew that it was lost, but also that it had to fight. Though not lacking in at least passive support among the Munich workers, the Soviet Republic horrified the conservative and Catholic peasantry and the notably reactionary middle class of Bavaria to the point where they welcomed the joint invasion of government troops and Free Corps from all over Germany (including a Bavarian Free Corps). The Soviet Republic ended on May 1 and was drowned in blood. Eugen Levine its ablest leader, was one of the victims.

He died comparatively young, and it is impossible to say what this impressive Russian, a figure closer by origin and sympathy to Lenin's Bolsheviks than to most German revolutionaries of the time, would have achieved had he lived. There is little point in speculating about it. We can only welcome this most valuable memoir in which his widow has made him live again for us, and incidentally provided a notable addition to our knowledge of the German tragedy of 1918-19, and to our understanding of the revolutionaries and revolutions of our century.

(6) Sebastian Haffner, Failure of a Revolution: Germany, 1918-19 (1973)

Never before was a revolutionary party forced into action in an inflammable situation against its will and with such cynicism. Never were the militant workers so severely punished for it. Never was a game so clearly envisaged by a superior, not only "equal" opponent. Never had a revolutionary party resisted with such determination taking part in an ostensibly revolutionary action. Never had a revolutionary party to master such a bizarre, daily changing situation.

(7) Eugen Levine, letter to Rose Levine (12th May, 1919)

At last I can send you a few words, my love, my dear. You were all the time beside me and my heart rejoiced when I thought of the last period of our life.

During all those desperate hours, hours of terror, I was full of those memories. I recalled our talks, your words, your kisses and caresses. Don't be sad Oslishechko. I am cheerful and full of energy. In spite of all the distress, I am looking to the future with confidence. As to us, I firmly hope that we shall be together very soon. And together with the child before my departure.

I am writing in a great hurry, my own one. The deliverer of the letter has to leave. I kiss you, kiss your eyes, lips, shoulders, kiss you, fondle you and feel the joy of your presence. Don't despair Oslishechko. Your flowers gave me great pleasure. I knew they would come, relished them in advance and enjoyed them when they really arrived. They were brought to me by the deliverer of this letter. I am fond of him and trust him like a brother. Speak to him freely.

I kiss you, kiss you my love. I thank you again for the last days. I am waiting, waiting ardently for more and more of them.

(8) Eugen Levine, letter to Rose Levine (29th May, 1919)

It is getting serious. On Monday the trial begins. This sudden haste is disquieting. It was intended to interrogate innumerable witnesses - but it suddenly seems unnecessary.

And so it is coming to an end, dearest, dearest, dearest! Daily, hourly I am thinking of you. I speak to you, hold you in my arms, console you, Oslik, little Oslik! I could not write all those days. I had a tiny little flame of hope. And to keep my chin up, I artificially fanned it. Lived as if nothing was looming over me. Ate, drank, read. But in these pages I must be honest. Should I continue my self-deception here? No, I could not do it. I was writing to you! To you I could not lie. And had I told you the truth? Then all my laboriously constructed house of cards would have collapsed. And so I gave up writing. And yet I was always with you and waited daily, hourly to see you, yourself. In vain. Shall I see you again? Darling, darling, dearest darling!

I am writing with clenched teeth. When the warder looks through the iron bars, he must not see how I feel. Dearest, dearest, I kiss you!

I am very sad, I am filled with such deep sadness. Death itself does not concern me. A few last minutes, the rattle of the guns, perhaps my last salute to the world revolution. Oh, it is not that. Not death, not dying, but parting with life. But how terrible when life is meaningless and one is only obsessed with the fear of death. No, in spite of my sadness, I am serene and happy. And for this I thank you, dearest.

Without you my life would not be complete. Yes, it was made rich and purposeful through my work, through the privilege of taking part in this struggle. But you have brought fulfilment. Dearest, dearest, dearest. I kiss your forehead, eyes and lips and thank you for everything, everything. Thank you for your gift to me of yourself; thank you for my little boy who will live on as part of me; thank you also for myself whom you have changed and improved. Thank you above all for yourself for you, for you.

(9) Eugen Levine, speech in court (2nd June, 1919)

The Proletarian Revolution has no need of terror for its aims; it detests and abhors murder. It has no need of these means of struggle, for it fights not individuals but institutions. How then does the struggle arise? Why, having gained power, do we build a Red Army? Because history teaches us that every privileged class has hitherto defended itself by force when its privileges have been endangered. And because we know this; because we do not live in cloud-cuckoo-land; because we cannot believe that conditions in Bavaria are different - that the Bavarian bourgeoisie and the capitalists would allow themselves to be expropriated without a struggle - we were compelled to arm the workers to defend ourselves against the onslaught of the dispossessed capitalists...

I am coming to a close. During the last six months I have no longer been able to live with my family. Occasionally my wife could not even visit me. I could not see my three-year-old boy because the police have kept a vigilant watch on us.

Such was my life and it is not compatible with lust for power or with cowardice. When Toller, who tried to persuade me to proclaim the Soviet Republic, in his turn accused me of cowardice, I said to him: "What do you want? The Social Democrats start, then run away and betray us; the Independents fall for the bait, join us, and later let us down, and we Communists are stood up against the wall."

We Communists are all dead men on leave. Of this I am fully aware. I do not know if you will extend my leave or whether I shall have to join Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In any case I await your verdict with composure and inner serenity. For I know that, whatever your verdict, events cannot be stopped. The Prosecuting Counsel believes that the leaders incited the masses. But just as leaders could not prevent the mistakes of the masses under the pseudo-Soviet Republic, so the disappearance of one or other of the leaders will under no circumstances hold up the movement.

And yet I know, sooner or later other judges will sit in this Hall and then those will be punished for high treason who have transgressed against the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Pronounce your verdict if you deem it proper. I have only striven to foil your attempt to stain my political activity, the name of the Soviet Republic with which I feel myself so closely bound up, and the good name of the workers of Munich. They - and I together with them - we have all of us tried to the best of our knowledge and conscience to do our duty towards the International, the Communist World Revolution.