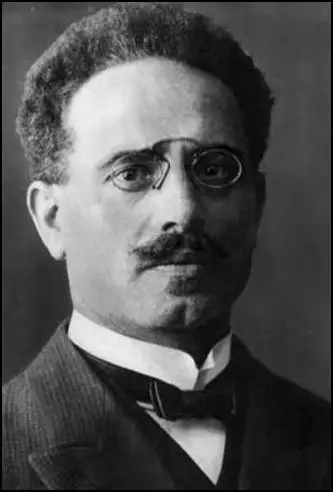

Karl Liebknecht

Karl Liebknecht, the son of Wilhelm Liebknecht and Natalie Reh, was born in Leipzig on 13th August, 1871. Two years previously, Liebknecht and August Bebel formed the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP) together. They also established a newspaper, Der Volksstaat.

In 1870 the two men used the newspaper to promote the idea that Otto von Bismarck had provoked France into war and called on workers from both countries to unite in overthrowing the ruling class. As a result, Bebel and Liebknecht were arrested and charged with high treason. In 1872, both men were convicted and sentenced to two years in the Königstein Fortress. (1)

Natalie Liebknecht was also heavily involved in politics. Her father, Karl Reh, was a member of the Frankfurt Parliament during the German Revolutions of 1848. On his release in 1874 Wilhelm Liebknecht was once again elected to the Reichstag. The following year he helped the SDAP merge with the General German Workers' Association (ADAV), an organisation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). In the 1877 General Election in Germany the SDP won 12 seats. This worried Otto von Bismarck, and in 1878 he introduced an anti-socialist law which banned Social Democratic Party meetings and publications. (2)

After the anti-socialist law ceased to operate in 1890, the SDP grew rapidly. However, Wilhelm Liebknecht had trouble from the left of the SDP. He came into conflict with Rosa Luxemburg over her militant articles in Vorwarts. Her biographer, Paul Frölich, has pointed out in his book, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940): "When Luxemburg published her articles on the Oriental question, even old Wilhelm Liebknecht set upon her with a letter which failed to refute any of her arguments, but which let fly at her a whole quiver of choice invectives, going so far as to make the scarcely veiled accusation that she had been bought by the Russian Okhrana - an action which, somewhat later, the old man admitted to be wrong and regretted." (3)

Karl Liebknecht and the Social Democratic Party

Karl Liebknecht studied law and political economy in Leipzig. He earned his doctorate at the University of Würzburg in 1897 and moved to Berlin in 1899, where he opened a lawyer's office with his brother, Theodor Liebknecht. In the dispute that took place in the Social Democratic Party, Liebknecht took the side of Rosa Luxemburg against his father. He also worked closely with the veteran left-winger, Franz Mehring. (4)

Liebknecht married Julia Paradies on 8th May 1900. Over the next couple of years the couple had two sons and a daughter. His father died on 7th August 1900 and now August Bebel became the dominant figure in the Social Democratic Party. Liebknecht began to argue for more radical action. In 1904 he joined forces with Clara Zetkin to suggest the use of the political mass strike to overthrow capitalism.

Paul Frölich, a fellow member of the SDP has argued: "He (Liebknecht) threw himself into the struggle with passionate intensity, displaying much independence and initiative which the party leaders tried to bridle, but in vain. He was one of the creators of the socialist youth movement, and was, in fact, the one who assigned it political tasks which went beyond purely educational objectives, namely the struggle against militarism." (5)

Anti-Militarism

Karl Liebknecht was in direct opposition to Eduard Bernstein. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands. His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Lenin and Leon Trotsky.

These views were not well received by August Bebel and other party leaders. Rosa Luxemburg explained to Clara Zetkin: "The situation is simply this: August Bebel, and still more so the others, have completely spent themselves on behalf of parliamentarism and in parliamentary struggles. Whenever anything happens which transcends the limits of parliamentarism, they are completely hopeless - no, even worse than that, they try their best to force everything back into the parliamentary mould, and they will furiously attack as an enemy of the people anyone who wants to go beyond these limits." (6)

Paul Frölich has argued: "The SPD divided into three clear tendencies: the reformists, who tended increasingly to espouse the ruling-class imperialist policy; the so-called Marxist Centre, which claimed to maintain the traditional policy, but in reality moved closer and closer to Bernstein's position; and the revolutionary wing, generally called the Left Radicals (Linksradikale)." (7)

At the Social Democratic Party Congress in September 1905, Luxemburg called for party members to be inspired by the attempted revolution in Russia. "Previous revolutions, especially the one in 1848, have shown that in revolutionary situations it is not the masses who have to be held in check, but the parliamentarians and lawyers, so that they do not betray the masses and the revolution." She then went onto quote from The Communist Manifesto: "The workers have nothing to lose but their chains; they had a world to win." (8)

August Bebel, the leader of the SDP, did not share Luxemburg's views that now was the right time for revolution. He later recalled: "Listening to all that, I could not help glancing a couple of times at the toes of my boots to see if they weren't already wading in blood." However, he preferred Luxemburg to Eduard Bernstein and he appointed her to the editorial board of the SPD newspaper, Vorwarts (Forward). In a letter to Leo Jogiches she wrote: "The editorial board will consist of mediocre writers, but at least they'll be kosher... Now the Leftists have got to show that they are capable of governing." (9)

Anti-Militarism of Karl Liebknecht

Karl Liebknecht became a leading figure in the anti-militarist section of the SDP. In 1907 he published Militarism and Anti-Militarism. In the book he argued: "Militarism is not specific to capitalism. It is moreover normal and necessary in every class-divided social order, of which the capitalist system is the last. Capitalism, of course, like every other class-divided social order, develops its own special variety of militarism; for militarism is by its very essence a means to an end, or to several ends, which differ according to the kind of social order in question and which can be attained according to this difference in different ways. This comes out not only in military organization, but also in the other features of militarism which manifest themselves when it carries out its tasks. The capitalist stage of development is best met with an army based on universal military service, an army which, though it is based on the people, is not a people’s army but an army hostile to the people, or at least one which is being built up in that direction."

He then went on to argue why the socialist movement should concentrate on persuading young people to adopt the philosophy of anti-militarism: "Here is a great field full of the best hopes of the working-class, almost incalculable in its potential, whose cultivation must not at any cost wait upon the conversion of the backward sections of the adult proletariat. It is of course easier to influence the children of politically educated parents, but this does not mean that it is not possible, indeed a duty, to set to work also on the more difficult section of the proletarian youth. The need for agitation among young people is therefore beyond doubt. And since this agitation must operate with fundamentally different methods – in accordance with its object, that is, with the different conditions of life, the different level of understanding, the different interests and the different character of young people – it follows that it must be of a special character, that it must take a special place alongside the general work of agitation, and that it would be sensible to put it, at least to a certain degree, in the hands of special organizations." (10)

A fellow member of the SDP, Paul Frölich has argued: "He (Liebknecht) never seemed to get tired... besides speaking at meetings, doing office work, and acting as defence counsel in court, he could still spend whole nights debating and drinking merrily with the comrades. And even if the street dust did cover his soul at times, it could not stifle the genuine enthusiasm which imbued all his activities. It was this devotion to the cause, the passionate temperament and this capacity for enthusiasm that Rosa valued. She recognised the true revolutionary in him, even if they sometimes disagreed on details of party tactics. They worked together and complemented each other very well, especially in the struggle against militarism and the danger of war." (11)

Rosa Luxemburg described Liebknecht to her friend, Hans Diefenbach. "Liebknecht... spent nearly all his time in parliament, meetings, commissions, conferences; running and rushing, always ready to jump from the commuter-train into the tram, and from the tram into a car; every pocket stuffed full of memo pads, his arms full of the latest newspapers which, of course, he never finds time to read; body and soul covered with street dust, and yet always with a kind and youthful smile on his face." (12)

At this time Germany became involved in an arms race with Britain. The Royal Navy built its first dreadnought in 1906. It was the most heavily-armed ship in history. She had ten 12-inch guns (305 mm), whereas the previous record was four 12-inch guns. The gun turrets were situated higher than user and so facilitated more accurate long-distance fire. In addition to her 12-inch guns, the ship also had twenty-four 3-inch guns (76 mm) and five torpedo tubes below water. In the waterline section of her hull, the ship was armoured by plates 28 cm thick. It was the first major warship driven solely by steam turbines. It was also faster than any other warship and could reach speeds of 21 knots. A total of 526 feet long (160.1 metres) it had a crew of over 800 men. It cost over £2 million, twice as much as the cost of a conventional battleship.

Germany built its first dreadnought in 1907 and plans were made for building more. The British government believed it was necessary to have twice the number of these warships than any other navy. David Lloyd George had a meeting with the German Ambassador, Count Paul Metternich, and told him that Britain was willing to spend £100 million to frustrate Germany's plans to achieve naval supremacy. That night he made a speech where he spoke out on the arms race: "My principle is, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, less money for the production of suffering, more money for the reduction of suffering." (13)

Kaiser Wilhelm II gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph in October 1908 where he outlined his policy of increasing the size of his navy: "Germany is a young and growing empire. She has a world-wide commerce which is rapidly expanding and to which the legitimate ambition of patriotic Germans refuses to assign any bounds. Germany must have a powerful fleet to protect that commerce and her manifold interests in even the most distant seas. She expects those interests to go on growing, and she must be able to champion them manfully in any quarter of the globe. Her horizons stretch far away. She must be prepared for any eventualities in the Far East. Who can foresee what may take place in the Pacific in the days to come, days not so distant as some believe, but days at any rate, for which all European powers with Far Eastern interests ought steadily to prepare?" (14)

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, had consistently described Germany as Britain's "secret and insidious enemy". He used his newspapers to urge an increase in defence spending and in October 1909 he commissioned Robert Blatchford, to visit Germany and then write a series of articles setting out the dangers. The German's, Blatchford wrote, were making "gigantic preparations" to destroy the British Empire and "to force German dictatorship upon the whole of Europe". He complained that Britain was not prepared for was and argued that the country was facing the possibility of an "Armageddon". (15)

Karl Liebknecht led the campaign against the building of more dreadnoughts. Other members of the Social Democratic Party who supported Liebknecht included Leo Jogiches, Franz Mehring, Clara Zetkin, Paul Frölich, Hugo Eberlein, August Thalheimer, Bertha Thalheimer, Käte Duncker, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck, Julian Marchlewski, Hermann Duncker and Anton Pannekoek. The leadership of the SDP agreed with the build-up of the armed forces in Germany and they saw a significant growth in their popularity. For example, in 1907 they won 43 seats in the Reichstag. Four years later they increased this to 110 seats. (16)

The First World War

On 4th August, 1914, Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy." (17)

Paul Frölich, a supporter of Liebknecht in the Social Democratic Party (SDP), argued: "On the day of the vote only one man was left: Karl Liebknecht. Perhaps that was a good thing. That only one man, one single person, let it be known on a rostrum being watched by the whole world that he was opposed to the general war madness and the omnipotence of the state - this was a luminous demonstration of what really mattered at the moment: the engagement of one's whole personality in the struggle. Liebknecht's name became a symbol, a battle-cry heard above the trenches, its echoes growing louder and louder above the world-wide clash of arms and arousing many thousands of fighters against the world slaughter." (18)

John Peter Nettl claims that two left-wing members of the SDP, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin, were horrified by these events. They had great hopes that the SDP, the largest socialist party in the world with over a million members, would oppose the war: "Both Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin suffered nervous prostration and were at one moment near to suicide. Together they tried on 2 and 3 August to plan an agitation against the war; they contacted 20 SPD members with known radical views, but they got the support of only Liebknecht and Mehring... Rosa sent 300 telegrams to local officials who were thought to be oppositional, asking their attitude to the vote in the Reichstag and inviting them to Berlin for an urgent conference. The results were pitiful." (19)

The Spartacus League

Karl Liebknecht campaigned against the war but decided against forming a new party and agreed to continue working within the SPD. Clara Zetkin was initially reluctant to join this anti-war faction. She argued: "We must ensure the broadest relationship with the masses. In the given situation the protest appears more as a personal beau geste than a political action... It is justified and nice to say that everything is lost, except one's honour. If I wanted to follow my feelings, then I would have telegraphed a yes with great pleasure. But now we must more than ever think and act coolly." (20)

However, by September, 1914, Zetkin was playing a significant role in the anti-war movement. She co-signed with Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Mehring, letters that appeared in socialist newspapers in neutral countries condemning the war. Above all Zetkin used her position as editor-in-chief of the Glieichheit and as Secretary of the Women's Secretariat of the Socialist International to propagate the positions of the anti-war movement. (21)

Clara Zetkin who later recalled: "The struggle was supposed to begin with a protest against the voting of war credits by the social-democratic Reichstag deputies, but it had to be conducted in such a way that it would be throttled by the cunning tricks of the military authorities and the censorship. Moreover, and above all, the significance of such a protest would doubtless be enhanced, if it was supported from the outset by a goodly number of well-known social-democratic militants." (22)

Karl Liebknecht continued to make speeches in public about the war: "The war is not being waged for the benefit of the German or any other peoples. It is an imperialist war, a war over the capitalist domination of the world market... The slogan 'against Tsarism' is being used - just as the French and British slogan 'against militarism' - to mobilise the noble sentiments, the revolutionary traditions and the hopes of the people for the national hatred of other peoples." (23)

In May 1915, Liebknecht published a pamphlet, The Main Enemy Is At Home! He argued that: "The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists. We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity." (24)

In December, 1915, 19 other deputies joined Karl Liebknecht in voting against war credits. The following year a series of demonstrations took place. Some of these were "spontaneous outbursts by unorganised groups of people, usually women: anger would flare when a shop ran out of food, or put its prices up, or when rations were suddenly cut." These demonstrations often led to bitter clashes between workers and the police. (25)

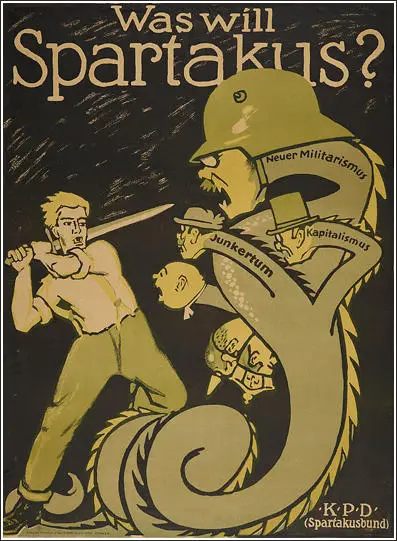

Over the next few months members of this group were arrested for their anti-war activities and spent several short spells in prison. This included Rosa Luxemburg, Ernest Meyer, Wilhelm Pieck and Hugo Eberlein. Other activists included Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi, Franz Mehring, Julian Marchlewski and Hermann Duncker. On the release of Luxemburg in February 1916, it was decided to establish an underground political organization called Spartakusbund (Spartacus League). The Spartacus League publicized its views in its illegal newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Like the Bolsheviks in Russia, they argued that socialists should turn this nationalist conflict into a revolutionary war. (26)

The group published an attack on all European socialist parties (except the Independent Labour Party): "By their vote for war credits and by their proclamation of national unity, the official leaderships of the socialist parties in Germany, France and England (with the exception of the Independent Labour Party) have reinforced imperialism, induced the masses of the people to suffer patiently the misery and horrors of the war, contributed to the unleashing, without restraint, of imperialist frenzy, to the prolongation of the massacre and the increase in the number of its victims, and assumed their share in the responsibility for the war itself and for its consequences." (27)

Eugen Levine was one of the first people to join the Spartacus League. He had been disturbed by the "new wave of national prejudice and chauvinism". His wife, Rosa Levine-Meyer, was shocked when he stated that the war would last "at least eighteen months or two years". This upset his mother who had been convinced by government propaganda that "the war would end by Christmas". Levine told Rosa Luxemburg that the "war would be accompanied by a severe world crisis and revolutionary shocks". He added that during a war "it is easier to convert thousands of workers than one single well-meaning intellectual". (28)

On 1st May, 1916, Liebknecht and Luxemburg, organised a anti-war demonstration on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. It was a great success and by eight o'clock in the morning around 10,000 people assembled in the square. The police charged at Karl Liebknecht who was about to speak to the large crowd. "For two hours after Liebknecht's arrest masses of people swirled around Potsdamer Platz and the neighbouring streets, and there were many scuffles with the police. For the first time since the beginning of the war open resistance to it had appeared on the streets of the capital." (29)

As a member of the Reichstag, Liebknecht had parliamentary immunity from prosecution. When the military judicial authorities demanded that this immunity was removed, the Reichstag agreed and he was placed on trial. On 28th June 1916, Liebknecht was sentenced to two years and six months hard labour. The day Liebknecht was sentenced, 55,000 munitions workers went on strike. The government responded by arresting trade union leaders and having them conscripted into the German Army.

Luxemburg responded by publishing a handbill defending Liebknecht and accusing members of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) who had removed his parliamentary immunity as being "political dogs". She claimed that: "A dog is someone who licks the boots of the master who has dealt him kicks for decades. A dog is someone who gaily wags his tail in the muzzle of martial law and looks straight into the eyes of the lords of the military dictatorship while softly whining for mercy... A dog is someone who, at his government's command, abjures, slobbers, and tramples down into the muck the whole history of his party and everything it has held sacred for a generation." (30)

Rosa Luxemburg was re-arrested on 10th July, 1916. So also was the seventy-year-old Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer and Julian Marchlewski. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics. (31)

The German Revolution

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (32)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (33)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Kiel soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (34)

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (35)

Karl Liebknecht, who had been released from prison on 23rd October, climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (36)

The Social Democratic Party press, fearing the opposition of the left-wing and anti-war Spartacus League, proudly trumpeted their achievements: "The revolution has been brilliantly carried through... the solidarity of proletarian action has smashed all opposition. Total victory all along the line. A victory made possible because of the unity and determination of all who wear the workers' shirt." (37)

Rosa Luxemburg was released from prison in Breslau on 8th November. She went to Cathedral Square, in the centre of the city, where she was cheered by a mass demonstration. Two days later she arrived in Berlin. Her appearance shocked her friends in the Spartacus League: "They now saw what the years in prison had done to her. She had aged, and was a sick woman. Her hair, once deep black, had now gone quite grey. Yet her eyes shone with the old fire and energy." (38)

Eugen Levine went on speaking tours in support of the Spartacus League and was encouraged by the response he received. According to his wife: "His first propaganda tour through the Ruhr and Rhineland was crowned with almost legendary success... They did not come to get acquainted with Communist ideas. At best they were driven by curiosity, or a certain restlessness characteristic of the time of revolutionary upheavels... Levine was regularly received with catcalls and outbursts of abuse but he never failed to calm the storm. He told me jokingly that he often had to play the part of a lion-tamer." (39)

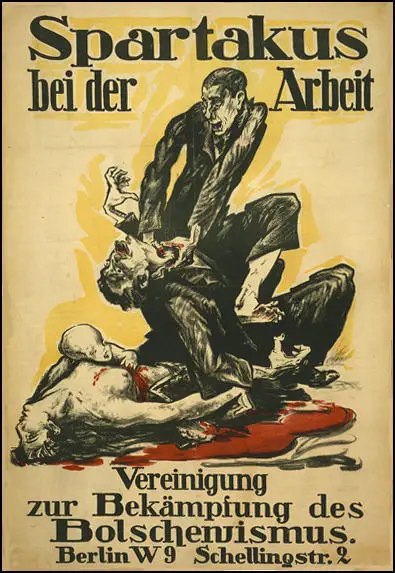

Ebert became concerned about the growing support for the Spartacus League and gave permission for the publishing of a Social Democratic Party leaflet that attacked their activities: "The shameless doings of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg besmirch the revolution and endanger all its achievements. The masses cannot afford to wait a minute longer and quietly look on while these brutes and their hangers-on cripple the activity of the republican authorities, incite the people deeper and deeper into a civil war, and strangle the right of free speech with their dirty hands. With lies, slander, and violence they want to tear down everything that dares to stand in their way. With an insolence exceeding all bounds they act as though they were masters of Berlin." (40)

Heinrich Ströbel, a journalist based in Berlin believed that some leaders of the Spartacus League overestimated their support: "The Spartakist movement, which also influenced a section of the Independents, succeeded in attracting a fraction of the workers and soldiers and keeping them in a state of constant excitement, but it remained without a hold on the great mass of the German proletariat. The daily meetings, processions, and demonstrations which Berlin witnessed... deceived the public and the Spartakist leaders into believing in a following for this revolutionary section which did not exist." (41)

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote. (42)

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League." (43)

Luxemburg was aware that the Spartacus League only had 3,000 members and not in a position to start a successful revolution. The Spartacus League consisted chiefly of innumerable small and autonomous groups scattered all over the country. John Peter Nettl has argued that "organisationally Spartakus was slow to develop... In the most important cities it evolved an organised centre only in the course of December... and attempts to arrange caucus meetings of Spartakist sympathisers within the Berlin Workers' and Soldiers' Council did not produce satisfactory results." (44)

Pierre Broué suggests that the large meetings helped to convince Karl Liebknecht that a successful revolution was possible. "Liebknecht, an untiring agitator, spoke everywhere where revolutionary ideas could find an echo... These demonstrations, which the Spartakists had neither the force nor the desire to control, were often the occasion for violent, useless or even harmful incidents caused by the doubtful elements who became involved in them... Liebknecht could have the impression that he was master of the streets because of the crowds which acclaimed him, while without an authentic organisation he was not even the master of his own troops." (45)

A convention of the Spartacus League began on 30th December, 1918. Karl Radek, a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee, argued that the the Soviet government should help the spread of world revolution. Radek was sent to Germany and at the convention he persuaded the delegates to change the name to the German Communist Party (KPD). The convention now discussed whether the KPD should take part in the forthcoming general election.

Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". (46) As Rosa Levine-Mayer explained the election "had the advantage of bringing the Spartakists closer to the broader masses and acquainting them with Communist ideas. Nor could a set-back, followed by a period of illegality, even if only temporary, be altogether ruled out. A seat in the Parliament would then be the only means of conducting Communist propaganda openly.It could also be foreseen that the workers at large would not understand the idea of a boycott and would not be persuaded to stay aloof; they would only be forced to vote for other parties." (47)

Luxemburg, Levi and Jogiches and other members who wanted to take part in elections were outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising." (48)

Emil Eichhorn had been appointed head of the Police Department in Berlin. One activist pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces." (49)

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other." (50)

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten." (51)

Paul Levi later reported that even with this provocation, the Spartacus League leadership still believed they should resist an open rebellion: "The members of the leadership were unanimous; a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat." (52)

Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck published a leaflet calling for a revolution. "The Ebert-Scheidemann government has become intolerable. The undersigned revolutionary committee, representing the revolutionary workers and soldiers, proclaims its removal. The undersigned revolutionary committee assumes provisionally the functions of government." Karl Radek later commented that Rosa Luxemburg was furious with Liebknecht and Pieck for getting carried away with the idea of establishing a revolutionary government." (53)

Although massive demonstrations took place, no attempt was made to capture important buildings. On 7th January, Luxemburg wrote in the Die Rote Fahne: "Anyone who witnessed yesterday's mass demonstration in the Siegesalle, who felt the magnificent mood, the energy that the masses exude, must conclude that politically the proletariat has grown enormously through the experiences of recent weeks.... However, are their leaders, the executive organs of their will, well informed? Has their capacity for action kept pace with the growing energy of the masses?" (54)

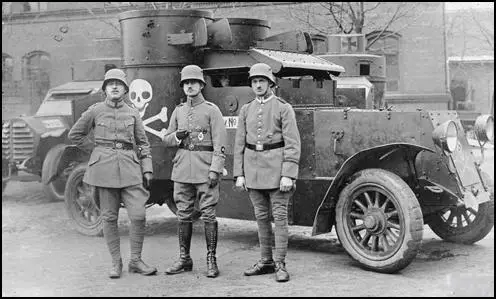

General Kurt von Schleicher, was on the staff of Paul von Hindenburg. In December 1919 he helped organize the Freikorps, in an attempt to prevent a German Revolution. The group was composed of "former officers, demobilized soldiers, military adventurers, fanatical nationalists and unemployed youths". Holding extreme right-wing views, von Schleicher blamed left-wing political groups and Jews for Germany's problems and called for the elimination of "traitors to the Fatherland". (55)

The Freikorps appealed to thousands of officers who identified with the upper class and had nothing to gain from the revolution. There were also a number of privileged and highly trained troops, known as stormtroopers, who had not suffered from the same rigours of discipline, hardship and bad food as the mass of the army: "They were bound together by an array of privileges on the one hand, and a fighting camaraderie on the other. They stood to lose all this if demobilised - and leapt at the chance to gain a living by fighting the reds." (56)

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, was also in contact with General Wilhelm Groener, who as First Quartermaster General, had played an important role in the retreat and demobilization of the German armies. According to William L. Shirer, the SDP leader and the "second-in-command of the German Army made a pact which, though it would not be publicly known for many years, was to determine the nation's fate. Ebert agreed to put down anarchy and Bolshevism and maintain the Army in all its tradition. Groener thereupon pledged the support of the Army in helping the new government establish itself and carry out its aims." (57)

On the 5th January, Ebert called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. Groener later testified that his aim in reaching accommodation with Ebert was to "win a share of power in the new state for the army and the officer corps... to preserve the best and strongest elements of old Prussia". Ebert was motivated by his fear of the Spartacus League and was willing to use "the armed power of the far-right to impose the government's will upon recalcitrant workers, irrespective of the long-term effects of such a policy on the stability of parliamentary democracy". (58)

The soldiers who entered Berlin were armed with machine-guns and armoured cars and demonstrators were killed in their hundreds. Artillery was used to blow the front off the police headquarters before Eichhorn's men abandoned resistance. "Little quarter was given to its defenders, who were shot down where they were found. Only a few managed to escape across the roofs." (59)

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal." (60)

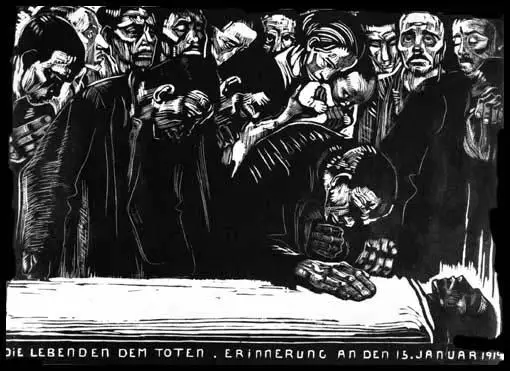

On the morning of Liebknecht's funeral Käthe Kollwitz visited the Liebknecht home to offer sympathy to the family. At their request, she made drawings of him in his coffin. She noted that there were red flowers around his forehead, where he had been shot. She wrote in her journal: "I am trying the Liebknecht drawing as a lithograph... Lithography now seems to be the only technique I can still manage. It's hardly a technique at all, its so simple. In it only the essentials count." (61)

Primary Sources

(1) Karl Liebknecht, Militarism and Anti-Militarism (1907)

Militarism is not specific to capitalism. It is moreover normal and necessary in every class-divided social order, of which the capitalist system is the last. Capitalism, of course, like every other class-divided social order, develops its own special variety of militarism; for militarism is by its very essence a means to an end, or to several ends, which differ according to the kind of social order in question and which can be attained according to this difference in different ways. This comes out not only in military organization, but also in the other features of militarism which manifest themselves when it carries out its tasks.

The capitalist stage of development is best met with an army based on universal military service, an army which, though it is based on the people, is not a people’s army but an army hostile to the people, or at least one which is being built up in that direction.

Sometimes it appears as a standing army, sometimes as a militia force. The standing army, which is not peculiar to capitalism appears as its most developed, even as its normal form.

The army of the capitalist social order, like the army of any other class-divided social order, fulfils a double role.

It is first of all a national institution, designed for external aggression or for protection against an external danger; in short designed for use in cases of international complication or, to use a military phrase, for use “against the external enemy”.

This function of the army is in no sense eliminated by the latest developments. For capitalism war is in fact, to use the words of Moltke, “a link in God’s world order”. In Europe itself there is admittedly something of a tendency for certain causes of war to be eliminated: the probability of war breaking out in Europe is decreasing, in spite of Alsace-Lorraine and the anxiety caused by the French trinity of Clemenceau, Pichon and Picquart, in spite of the Eastern question, in spite of Pan-Islamism and in spite of the revolution taking place in Russia. On the other hand new and highly dangerous sources of tension have arisen in consequence of the aims of commercial and political expansion pursued by the so-called civilized states, sources which have been handed down to us by the Eastern question and Pan-Islamism in the first instance, and as a consequence of world policy, and especially colonial policy, which - as Billow himself unreservedly acknowledged in the German Reichstag on November 14, 1906 - conceals countless possibilities of conflict. This policy has at the same time pushed forward ever more energetically two other forms of militarism: naval militarism and colonial militarism. We Germans know a few things about this development!

Navalism, naval militarism, is the twin brother of militarism on land and bears all its repulsive and virulent features. It is at present, to a still higher degree than militarism on land, not only the consequence but also the cause of international dangers, of the danger of a world war.

(2) Karl Liebknecht, Militarism and Anti-Militarism (1907)

The attempt to develop special anti-militarist propaganda in Germany has been resisted by influential leaders of the movement, who say that there is no Social-Democratic Party in the whole world which fights militarism as hard as German Social-Democracy. There is much truth in this. Ever since the German Reich has existed ruthless and tireless criticism has been levelled by the German Social-Democrats in parliament and in the press against militarism, the whole of its content and its harmful effects. It has collected material to indict militarism, enough to build a gigantic funeral pyre, and has waged the struggle against militarism as part of its general agitation with great energy and tenacity. In this respect our Party needs neither defence nor praise. Its deeds speak for themselves. Nevertheless, there is more to be done.

We by no means deny that the struggle waged against militarism has met with great success and that the form of the struggle has been well adapted to the goal. Nor do we deny that this kind of struggle will remain useful, and even indispensable, in the future, and bring more successes. But that does not settle the question. It does not resolve the problem of the education of young people, which is the most important part of the fight against militarism.

It is of course true that our general agitation opens people’s eyes, and every anti-capitalist and Social-Democrat is per se an excellent and reliable anti-militarist. The anti-militarist side of our general educational work leaves no doubt on this point. But to whom is our general agitation directed? It is and was rightly and necessarily designed for the adult man and woman worker. But we want to win over not only the adult workers, but also the children of the proletariat, the working-class youth. For the working-class youth is the working class-to-be, he is the future of the proletariat. “He who has the youth, has the future.”

At this point someone will retort: He who has the parents has the children of these parents, he has the youth! In any case it would be a wretched Social-Democrat who did not try his best to fill his children with the Social-Democratic spirit, and bring them up as Social-Democrats. It may be that the influence of the parents – together with the influence of the economic, social and political conditions under which the working-class youth grows up, but which, though the most important and obvious means of agitation and enlightenment, cannot be influenced by Party activity and must therefore be disregarded here – can easily overcome all the cunning of the attempts of reaction and capitalism to capture the child’s mind. But this fact clearly does not refute our point. One cannot settle things so easily. In fact it is precisely a careful examination of the above trend of thought which shows where the failing in our present agitation lies, a failing which is growing continually more serious and urgently demands a solution.

“Every Social-Democrat brings up his children as Social-Democrats.” But only to the best of his ability. This is the basis of the first important failing. How many people have a general understanding of how to teach, even if they have the time and inclination, and how many Social-Democratic workers, even if they have the best of intentions, have the necessary leisure and the necessary knowledge to educate their children? And in how many cases do the women and other politically backward members of the family rather unfortunately constitute a serious counterweight to whatever educational influence the class-conscious father may possess? If the Party wants to do its duty properly it must go into every nook and corner to help with home education. What is required is general educational and especially agitational work among young people, which must have an anti-militarist aspect.

But further: how many proletarians are really educated in Social-Democracy, educated to the point where they themselves can educate others on the fundamental principles of the standpoint and goals of the movement? How many workers are there in time of peace so ready for sacrifice and so tireless that they are even willing to undertake, to the best of their ability, the tough, painful, continuous hourly and daily work of education? And apart from those who are a quarter or half-educated, and the lukewarm who form an enormous mass: what a huge number of workers are total strangers to Social-Democracy! Here is a great field full of the best hopes of the working-class, almost incalculable in its potential, whose cultivation must not at any cost wait upon the conversion of the backward sections of the adult proletariat. It is of course easier to influence the children of politically educated parents, but this does not mean that it is not possible, indeed a duty, to set to work also on the more difficult section of the proletarian youth.

The need for agitation among young people is therefore beyond doubt. And since this agitation must operate with fundamentally different methods – in accordance with its object, that is, with the different conditions of life, the different level of understanding, the different interests and the different character of young people – it follows that it must be of a special character, that it must take a special place alongside the general work of agitation, and that it would be sensible to put it, at least to a certain degree, in the hands of special organizations. Our agitational work, with the growth in its volume and the increase in the Party’s tasks, and at a time when the decisive struggles are drawing ever nearer, has become so extraordinarily extensive and complex that the need for it to be divided up becomes more pressing – a division of labour of whose relative, but only relative, difficulties we are not by any means ignorant.

(3) Justice (17th December 1914)

The Berner Tagewacht publishes the full text of Karl Liebknecht’s protest in the Reichstag against the voting of the war credits. The protest was suppressed in the Reichstag, and no German paper has published it. It appears that seventeen Social-Democratic members expressed their opposition to the credits on December 2, but Karl Liebknecht’s was the only vote recorded against them.

(4) Karl Liebknecht, The Main Enemy Is At Home!, leaflet (May 1915)

The main enemy of the German people is in Germany: German imperialism, the German war party, German secret diplomacy. This enemy at home must be fought by the German people in a political struggle, cooperating with the proletariat of other countries whose struggle is against their own imperialists.

We think as one with the German people – we have nothing in common with the German Tirpitzes and Falkenhayns, with the German government of political oppression and social enslavement. Nothing for them, everything for the German people. Everything for the international proletariat, for the sake of the German proletariat and downtrodden humanity.

The enemies of the working class are counting on the forgetfulness of the masses – provide that that be a grave miscalculation. They are betting on the forbearance of the masses – but we raise the vehement cry: "How long should the gamblers of imperialism abuse the patience of the people? Enough and more than enough slaughter! Down with the war instigators here and abroad!"

(5) Rosa Luxemburg, letter to Hans Diefenbach (30th March 1917)

You probably know how he (Karl Liebknecht) has lived for many years: practically only in parliament, meetings, commissions, conferences; running and rushing, always ready to jump from the commuter-train into the tram, and from the tram into a car; every pocket stuffed full of memo pads, his arms full of the latest newspapers which, of course, he never finds time to read; body and soul covered with street dust, and yet always with a kind and youthful smile on his face.

(6) Paul Frölich, Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940)

He (Liebknecht) never seemed to get tired... besides speaking at meetings, doing office work, and acting as defence counsel in court, he could still spend whole nights debating and drinking merrily with the comrades. And even if the street dust did cover his soul at times, it could not stifle the genuine enthusiasm which imbued all his activities. It was this devotion to the cause, the passionate temperament and this capacity for enthusiasm that Rosa valued. She recognised the true revolutionary in him, even if they sometimes disagreed on details of party tactics. They worked together and complemented each other very well, especially in the struggle against militarism and the danger of war.

(7) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

Karl Radek had furnished me in Moscow with introductions to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, the famous Spartakist leaders in Germany. So I began to search for them and, after a while, I found the headquarters of the Spartakusbund, the most revolutionary of all the German Left parties. After my credentials had been carefully inspected, I was taken to see Rosa Luxemburg.

A slight little woman, she showed at once a powerful intellect and a quiet grasp of any given situation. She had heard about me and of the fact that I had taken up a strong stand against the Allied intervention in Russia. She proceeded to question me about the situation in Russia. I told her how the White Counter-Revolution had been beaten on the Volga and thrown back to Siberia, but that Lenin had spoken to me not long before with some apprehension of the possibility of Allied military support for the Russian Whites in South Russia, now that the Dardanelles and Black Sea were open to British and French warships. Then she asked me a question, the significance of which I did not appreciate at the time. She asked me if the Soviets were working entirely satisfactorily. I replied, with some surprise, that of course they were. She looked at me for a moment, and I remember an indication of slight doubt on her face, but she said nothing more. Then we talked about something else and soon after that I left.

Though at the moment when she asked me that question I was a little taken aback, I soon forgot about it. I was still so dedicated to the Russian Revolution, which I had been defending against the Western Allies' war of intervention, that I had had no time for anything else. But a week or two later I began to hear that Rosa Luxemburg differed from Lenin on several matters of revolutionary policy, and especially about the role of the Communist Party in the Workers' and Peasants' Councils, or Soviets. She did not like the Russian Communist Party monopolizing all power in the Soviets and expelling anyone who disagreed with it. She feared that Lenin's policy had brought about, not the dictatorship of the working classes over the middle classes, which she approved of but the dictatorship of the Communist Party over the working classes. The dictatorship of a class - yes, she said, but not the dictatorship of a party over a class. Later, I began to see that Luxemburg had much wisdom in her attitude, though it was not apparent to me at the time. Looking back, it seems that she was not so critical of Lenin's tactics for Russia. She did not want them applied to Germany. Alas, she never lived to use her influence on her colleagues in the Spartakusbund for more than a few weeks after I saw her.

(8) Karl Liebknecht, speech (January, 1919)

Friends, Comrades, Brothers! From under the blows of the world war, amidst the ruin which has been created by Tzarist Imperialist society - the Russian Proletariat erected its State - the Socialist Republic of Workers, Peasants and Soldiers. This was created in spite of an attitude of misconception, hatred and calumny. This republic represents the greatest basis for that universal socialist order, the creation of which is at the present time the historic task of the International Proletariat. The Russian revolution was to an unprecedented degree the cause of the proletariat of the whole world becoming more revolutionary. Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary are already in the throes of revolution; revolution is awakening in Germany. But there are obstacles in the way of the victory of the German proletariat. The mass of the German people are with us, the power of the accused enemies of the working class has collapsed; but they are nevertheless making all attempts to deceive the people, with a view of protracting the hour of the liberation of the German people. The robbery and violence of German Imperialism in Russia, as well as the violent Brest-Litovsk peace and the Bucharest peace have consolidated and strengthened the Imperialists of the Allied countries; - and this is the reason why the German Government are endeavouring to utilize the Allied attack upon Socialist Russia for the purpose of retaining power. You have no doubt heard how Willhelm II, who, now that Tzarism has perished, is the representative of the basest form of reaction, - a few days ago made use of intervention in the affairs of proletarian Russia by the Allied Empires for the purpose of raising a new war agitation amongst the working masses. We must not permit our ignoble enemies to make use of any democratic means and institutions for their purpose; the proletariat of the Allied countries must allow no such thing to occur. We know that you have already raised your voice to protest against the machinations of your governments; but the danger is growing ever greater and greater. A united front of world Imperialism against the proletariat is being realised, in the first instance, in the struggle aga inst the Russian Soviet Republic. This is what I warn you against. The proletariat of the world must not allow the flame of the Socialist Revolution to be extinguished, or all its hopes and all its powers will perish. The failure of the Russian Socialist Republic will be the defeat of the proletariat of the whole world. Friends, comrades, brothers arise against your rulers! Long live the Russian workers, soldiers and peasants! Long live the Revolution of the French, English, American proletariat! Long live the liberation of the workers off all countries from the infernal chasm of war, exploitation and slavery!

(9) Bertram D. Wolfe, Strange Communists I Have Known (1966)

In the third week of December, the masses, as represented in the First National Congress of the Councils of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, rejected by an overwhelming majority the Spartacan motion that the Councils should disrupt the Constituent Assembly and the Provisional Democratic Government and seize power themselves.

In the light of Rosa's public pledge, the duty of her movement seemed clear: to accept the decision, or to seek to have it reversed not by force but by persuasion. However, on the last two days of 1918 and the first of 1919, the Spartacans held a convention of their own where they outvoted their "leader" once more. In vain did she try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising. Almost alone in her party, Rosa Luxemburg decided with a heavy heart to lend her energy and her name to their effort.

The Putsch, wth inadequate forces and overwhelming mass disapproval except in Berlin, was as she had predicted, a fizzle. But neither she nor her close associates fled for safety as Lenin had done in July, 1917. They stayed in the capital, hiding carelessly in easily suspected hideouts, trying to direct an orderly retreat. On January 16, a little over two months after she had been released from prison, Rosa Luxemburg was seized, along with Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck. Reactionary officers murdered Liebknecht and Luxemburg while "taking them to prison." Pieck was spared, to become, as the reader knows, one of the puppet rulers of Moscow-controlled East Germany.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Who Set Fire to the Reichstag? (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)