Ernst Toller

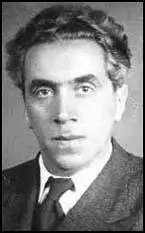

Ernst Toller, the son of Mendel Toller, a successful Jewish wholesale grain merchant, was born in Samotschin in 1893. His father became one of the town's councillors. "The Samotschin of Toller's childhood was an intensely German town. Its proximity to Poland heightened German national feeling even among the town's Jewish inhabitants." (1)

Toller admitted: "We children called the Poles 'Polacks' and firmly believed that they were the descendants of Cain, who slew Abel and was branded by God. Against the Poles, Jews and Germans showed a united front. The Jews looked upon themselves as the pioneers of German culture, and their houses in these little towns became cultural centers where German literature, philosophy and art were cultivated with a pride and an assiduousness which bordered on the ridiculous. The Poles were declared to be no patriots - the poor Poles whose children at school were forbidden their mother-tongue, whose lands had been confiscated by the German State." (2)

At the age of ten Toller became seriously ill and had to undergo a major operation. For a period he was only able to walk with the aid of crutches. In 1905 he was sent to boarding school in Bromberg. Later Toller described it as a "school of miseducation and militarization". The values it propagated were nationalistic, militaristic and socially conservative. "It was a system which only succeeded in nourishing his spirit of rebellion, an experience which prompted his later interest in socialist education." (3)

Toller wrote in his autobiography: "Preparation for practical life is called mathematics. We learn formulae which we do not understand and soon forget. We learn history for the sake of dates. It is quite unimportant to see the history of the world in proper perspective, to understand the relation of cause and effect; but it is the greatest possible importance that we should know the dates of battles and coronations. Napoleon was a thief who robbed Germany of her treasures, taking even the tiles from the roofs of the churches. If you do not answer the master's questions in that spirit you are a marked man, and will come to a bad end. The masters give us the same subjects for essays that they were given when they were at school, time-honoured phrases, rusty with age. And woe betide the pupil who brings his own original ideas to them. Henceforward he is a suspected person, a revolutionary. He must learn the fear of God, he must learn submission and obedience." (4)

Toller was not a good student but developed a strong interest in literature and by the age of eighteen was writing stories, plays and poems and had several articles published in the local newspaper. However, he later admitted that he was not interested in politics and was as receptive as most of his contemporaries for the prevailing atmosphere of strident nationalism. In 1911 the German government ordered a gunboat to the port of Agadir, allegedly to protect German interests threatened by French expansion in Morocco. War fever spread rapidly. Toller remembered that he and his school-mates greeted the crisis with excitement and enthusiasm. (5)

In 1914 Toller moved to France where he studied at the University of Grenoble. Toller spent little time attending lectures: "I preferred to spend my time in the German Students' Union. We used to discuss Nietzsche and Kant, and sitting upright on our stools we drank glass after glass of light beer... I rarely went to the University. The lectures bored me, and most of the professors reminded me of shop-walkers: they praised the various aspects of the official culture in phrases that sounded like advertising slogans. Grenoble is a regular French propaganda factory." (6)

Six months after arriving, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. On 28th July, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The following day the Kaiser Wilhelm II promised to Britain that he would not annex any French territory in Europe provided the country remained neutral. This offer was immediately rejected by Sir Edward Grey in the House of Commons. On 3rd August, 1914, Germany declared war on France and the following day Britain declared war on Germany. (7)

Toller headed back home and was in one of the last trains to be allowed out of France before the border was closed. Toller, like most Germans, accepted that it was his duty to join the German Army and defend the Fatherland. At first he was rejected: "The barracks were overflowing with recruits, and I was rejected by both infantry and cavalry. I had to wait. No more volunteers were required. I wandered about the streets of Munich, and in the Stachusplatz I found a raging mob. Somebody had heard two women speaking French, and they were immediately surrounded and set upon. They protested that they were Germans, but it did not avail them in the least; with torn clothes, disheveled hair and bleeding faces they were taken off by the police." (8)

Ernst Toller and the First World War

Eventually he was allowed to enlist in the First Bavarian Foot Artillery Regiment. Richard Dove has argued that Toller's patriotic commitment was typical of the Jewish community in general. Prominent liberal Jewish intellectuals, such as Alfred Kerr, Maximilian Harden, Siegfried Jacobsohn and Kurt Tucholsky were converted overnight to a militant patriotism. "The number of Jews who died fighting for Kaiser and country was proportionally greater than any other racial group in the Reich, including the 'pure' Germans: it was their last desperate attempt at assimilation." (9)

In March 1915, he was sent to the Western Front. When he heard the news he wrote in his diary: "How happy I am to go to the front at last. To do my bit. To prove with my life what I think I feel." (10) After six months working as an observer with an artillery unit, Toller asked to transferred to the front-line trenches. One reason for this request was that because he felt he was being victimized by his platoon commander. Like at school, Toller believed he was being persecuted because he was Jewish. Toller was also anxious to see more action. (11)

Toller served at Bois-le-Pretre and then at Verdun. In his autobiography, I Was a German (1933), Toller describes the misery of serving on the front-line: "One night we heard a cry, the cry of one in excruciating pain; then all was quiet again. Someone in his death agony, we thought. But an hour later the cry came again. It never ceased the whole night. Nor the following night. Naked and inarticulate the cry persisted. We could not tell whether it came from the throat of German or Frenchman. It existed in its own right, an agonized indictment of heaven and earth. We thrust our fingers into our ears to stop its moan; but it was no good; the cry cut like a drill into our heads, dragging minutes into hours, hours into years. We withered and grew old between those cries. Later we learned that it was one of our own men hanging on the wire. Nobody could do anything for him; two men had already tried to save him, only to be shot themselves. We prayed desperately for his death. He took so long about it, and if he went on much longer we should go mad. But on the third day his cries were stopped by death." (12)

Appalled by the physical slaughter that he witnessed in the trenches, Toller began to question the nationalistic propaganda that he had experienced since his schooldays. He wrote an article for the arts journal, Der Kunstwart, that was rejected as being unsuitable "in view of the current state of public opinion". It included the passage: "Most people have no imagination. If they could imagine the sufferings of others, they would not make them suffer so. What separated a German mother from a French mother? Slogans which deafened us so that we could not hear the truth." (13)

Unable to get his prose published in journals, he began writing poems: "A dung heap of rotting corpses: Glazed eyes, bloodshot, Brains split, guts spewed out. The air poisoned by the stink of corpses. A single awful cry of madness. Oh, women in France, Women of Germany. Regard your men folk! They fumble with torn hands. For the swollen bodies of their enemies. Gestures, stiff in death, become the touch of brotherhood. Yes, they embrace each other, Oh, horrible embrace! I see and see and am struck dumb. Am I a beast, a murderous dog? Men violated. Murdered. (14)

Toller later recalled an incident that converted him to pacifism and internationalism: "I saw the dead without really seeing them. As a boy I used to go to the Chamber of Horrors at the annual fair, to look at the wax figures of Emperors and Kings, of heroes and murderers of the day. The dead now had that same unreality, which shocks without arousing pity." Then one day: "I stood in the trench cutting into the earth with my pick. The point got stuck, and I heaved and pulled it out with a jerk. When it came a slimy, shapeless bundle, and when I bent down to look I saw that wound round my pick were human entrails. A dead man was buried there. A dead man. What made me pause then? Why did those words so startle me? They closed upon my brain like a vice; they choked my throat and chilled my heart. Three words, like any other three words. A dead man. I tried to thrust the words out of my mind; what was there about them that they should so overwhelm me? And suddenly, like light in darkness, the real truth broke in upon me; the simple fact of Man, which I had forgotten, which had lain deep buried and out of sight; the idea of community, of unity. A dead man. Not a dead Frenchman. Not a dead German. A dead man. All these corpses had been men; all these corpses had breathed as I breathed; they had a father, a mother, a woman whom they loved, a piece of land which was theirs, faces which expressed their joys and their sufferings, eyes which had known the light of day and the colour of the sky. At that moment of realization I knew that I had been blind because I had wished not to see; it was only then that I realised, at last, that all these dead men, French and Germans, were brothers, and I was the brother of them all." (15)

In May 1916 Toller suffered a physical and nervous breakdown. Taken to a hospital near Strasbourg, where he remained for about two months before being transferred to a sanatorium near Munich for further treatment. His doctor diagnosed him as suffering from "physical exhaustion and a complete nervous breakdown". In other words, shellshock. After being transferred to a hospital near Mainz, and on 4th January 1917, he was discharged from the German Army as "unfit for active service". (16)

Toller returned to his studies and now went to Heidelberg University where he met the pioneering sociologist, Max Weber. Although the two men became close friends, they disagreed about the war. Weber believed that Germany must continue to prosecute the war, whereas Toller favoured a negotiated peace. (17) Toller also returned to writing poetry. His views on the subject had been dramatically changed by his experiences on the Western Front. He completely rejected the idea of "art for art's sake". The purpose of art was no longer simply aesthetic. Poetry had to confront the issues of the day, and in a time of mass slaughter, the only issue was the war. (18)

Toller believed that it was his duty as a human being to write political poetry. The role of the poet was not only to "decry the war, but to lead humanity towards his vision of a peaceful, just and communal society". In the poem, To the Mothers, he included this message to poets writing about the war: "Dig deeper into your pain, Let it strain, etch, gnaw. Stretch out arms raised in grief. Be volcanoes, glowing sea: let pain bring forth deeds... I accuse you, you poets, wanton with words, words, words... Cowardly hiding in your paper-basket. On to the rostrum, accused!" (19)

Toller, who by 1917 was both a socialist and pacifist, formed the Cultural and Political League of German Youth, an organisation which called for an end to the war. The main socialist party, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), supported the war and so Toller joined the anti-war Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). At this time he came under the influence of Gustav Landauer, the author of Call to Socialism (1911). Landauer was an anarcho-socialist, whose ideas derived from Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Peter Kroptkin. (20)

Toller was especially hostile to the nationalist and anti-semitic, German Fatherland Party, who had accused him of betraying his country: "You misuse the word Fatherland. Your private interests are not the interests of the people. We know no foreign power can crush our culture, but we repudiate any attempt to force our own culture upon another nation. Our goal is not aggrandizement, but cultural enrichment; it is spiritual not material development. We want to rouse the apathetic and indifferent into action, and we heartily respect those students in other countries who have already begun to protest against the unthinkable stupidity and horror of the war." (21)

Landauer rejected the theories of Karl Marx and described Marxism as "the bane of our time and the curse of the socialist movement". He disagreed with Marx's scientific approach to socialism. Socialism, he maintained, was not the result of a particular stage of material development, but the product of human will: "The possibility of socialism does not depend on any form of technology or the satisfaction of material needs. Socialism is possible at any time, if enough people want it." Landauer argued that: "It is essential that we understand socialism, the struggle for new relations between men, as a spiritual movement... that there can only be new relations between men in so far as men who are moved by the spirit create them for themselves." (22)

Toller's political activities soon resulted in him being expelled from Heidelberg University. Toller now moved to Munich where he helped Kurt Eisner, a veteran of anti-war demonstrations, to organize a munitions workers' strike. Eisner told the workers: "Unite with us to enforce a peace which will ensure freedom and happiness for all mankind in the building of a new world... The struggle for peace has begun. Workers of the world unite!" (23)

On 1st February, 1918, 8,000 workers withdrew their labour in Munich from factories producing war materials. A mass meeting the following day attracted over 6,000 strikers. Toller, Eisner and Sonja Lerch were the three main speakers and therefore become a leading figure in the strike movement. He later reported that "what attracted me was their struggle against the war". On 4th February, police arrested Toller at gunpoint. Toller, Eisner, Lerch and other trade union leaders were sent to Leonrodstrasse military prison and charged with "attempted treason". On 29th March, Lerch hanged herself in prison. Toller was released in May and was forced to serve in the army for the final months of the war. (24)

The Transformation (1918)

In the summer of 1917 Toller began work on the play, The Transformation. He finished the work while in prison during the early months of 1918. The play makes use of his experiences during the First World War and the political conflict he was having with his father. In the opening scene Friedrich, a young sculptor, feels that he is a social outcast. He is cut off from society by his Jewish race and from the attitudes of his family. To break out of this isolation, he volunteers for a colonial war, in which he sees an opportunity to prove himself: "Oh, the struggle will unite us all. The greatness of the times will make us all great... Now I can do my duty. Now I can prove that I am one of them." (25)

Richard Dove has pointed out: "Friedrich volunteers for a dangerous mission in order to prove his devotion to the Fatherland. It is only after the successful conclusion of this mission that he begins to perceive the brutal reality behind the fine words of patriotism. His realization is prefigured in the dream scene... in which four skeletons, representing humanity used and abused by war, are united in death, as they hang in the barbed wire in No Man's Land... At the end of the scene, they perform a 'danse macabre' to the music of the rattling bones of other corpses." (26)

In the final scene, Friedrich addresses the people who have gathered on the church square. He tells his audience that he is aware of the suffering and deprivation of their daily lives. The existing social order has twisted their lives. They are no longer men and women, merely the distorted likenesses of their true selves. To become men and women again, they must believe in themselves and their own humanity. "Now go to your rulers and proclaim to them with roaring organ voices that their power is only an illusion. Go to the soldiers and tell them to beat their swords into ploughshares. Go to the rich and show them their hearts, buried beneath rubbish. But be kind to them, for they too are poor and gone astray." (27)

The publisher, Kurt Wolff, congratulated Toller on writing an important play: "The whole work is of such compelling authenticity and honesty and contains so much blood, breath and pain of these times, that you will certainly have no need to be ashamed of the work - now or later. The Transformation will, in a very special sense, belong to the history of contemporary literature and the German revolution." (28)

The German Revolution

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (29)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (30)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon traveled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (31)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt, claimed: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (32)

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution. (33)

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (34)

Eisner made a speech pointing out the connections between art and revolution: "A politician who is not an artist is also no politician. It is a delusion of our unpolitical German people to believe you can achieve something in the world without such poetic power. The poet is no unpractical dreamer: he is the prophet of the future… Art should no longer be a refuge for those who despair of life, for life itself should be a work of art, and the state the greatest work of art." (35)

Chancellor, Max von Baden, decided to hand over power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy: "You have no right to proclaim the republic." (36)

Karl Liebknecht climbed to a balcony in the Imperial Palace and made a speech: "The day of Liberty has dawned. I proclaim the free socialist republic of all Germans. We extend our hand to them and ask them to complete the world revolution. Those of you who want the world revolution, raise your hands." It is claimed that thousands of hands rose up in support of Liebknecht. (37)

Bavarian Soviet Republic

In Bavaria, Kurt Eisner formed a coalition with the German Social Democrat Party (SDP) in the National Assembly. The Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) only received 2.5% of the total vote and he decided to resign to allow the SDP to form a stable government. He was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. (38)

It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria. One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city. (39)

Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency." (40) Ernst Toller was determined to support the revolution: "If our elders leave us in the lurch, the youth of all nations will establish the social commonwealth… We shall live for a new society, a new pure relationship between man and man, people and people." (41)

On 7th April, 1919, Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A fellow revolutionary, Paul Frölich later commented: "The Soviet Republic did not arise from the immediate needs of the working class... The establishment of a Soviet Republic was to the Independents and anarchists a reshuffling of political offices... For this handful of people the Soviet Republic was established when their bargaining at the green table had been closed... The masses outside were to them little more than believers about to receive the gift of salvation from the hands of these little gods. The thought that the Soviet Republic could only arise out of the mass movement was far removed from them. While they achieved the Soviet Republic they lacked the most important component, the councils." (42)

Ernst Toller, became a growing influence in the revolutionary council. Rosa Levine-Meyer claimed that: "Toller was too intoxicated with the prospect of playing the Bavarian Lenin to miss the occasion. To prove himself worthy of his prospective allies, he borrowed a few of their slogans and presented them to the Social Democrats as conditions for his collaboration. They included such impressive demands as: Dictatorship of the class-conscious proletariat; socialisation of industry, banks and large estates; reorganisation of the bureaucratic state and local government machine and administrative control by Workers' and Peasants' Councils; introduction of compulsory labour for the bourgeoisie; establishment of a Red Army, etc. - twelve conditions in all." (43)

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Meanwhile, conditions for the mass of the population were getting worse daily. There were now some 40,000 unemployed in the city. A bitterly cold March had depleted coal stocks and caused a cancellation of all fuel rations. The city municipality was bankrupt, with its own employees refusing to accept its paper currency." (44)

Toller was elected as the Commander of the first Red Army to be formed on German soil. Richard Dove has pointed out: "The paradox of a pacifist poet as military commander is one which has continued to fascinate the imagination up to the present day... In fact, all his actions as military commander reveal the inherent ambivalence of his position, torn between the principle of non-violence and the imperative of revolutionary solidarity. He had joined the spontaneous defence of Munich without hesitation but not without misgiving. He saw the prospect of armed conflict as 'a tragic necessity', a phrase which runs through all his subsequent accounts. He felt 'obliged' to join the workers; the same sense of moral obligation made him accept command of the Red Army". (45)

Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganising the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control. In a letter to his wife he commented that "in a few days the adventure will be liquidated". (46)

Levine argued that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed. (47)

Inspired by the events of the October Revolution, Levine ordered the expropriated of luxury flats and gave them to the homeless. Factories were to be run by joint councils of workers and owners and workers' control of industry and plans were made to abolish paper money. Levine, like the Bolsheviks had done in Russia, established Red Guard units to defend the revolution. (48)

Levine also suggested that: "We must speed up the building of revolutionary workers' organisations... We must create workers' councils out of the factory committees and the vast army of the unemployed." However, he urged caution: "We know from our experience in northern Germany that the Social Democrats often attempted to provoke premature actions which are the easiest to crush. A soviet republic cannot be proclaimed at a conference table. It is founded after a struggle by a victorious proletariat. The proletariat of Munich has not yet entered the struggle for power. After the first intoxication the Social Democrats will seize upon the first pretext to withdraw and thus deliberately betray the workers. The Independents will collaborate, then falter, then begin to waver, to negotiate with the enemy and turn unwittingly into traitors. And we as Communists will have to pay for your undertaking with blood?" (49)

Sebastian Haffner wrote in his book, Failure of a Revolution: Germany, 1918-19 (1973), that Eugen Levine was the communists best hope for leading a successful revolution as he had the same qualities as Leon Trotsky: "Eugen Levine, a young man of impulsive and wild energy who, unlike Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, probably possessed the qualities of a German Lenin or Trotsky." (50)

Johannes Hoffmann and other leaders of the Social Democratic Party in Munich fled to the town of Bamberg. Hoffman blocked food supplies to the city and began looking for troops to attack the Bavarian Soviet Republic. By the end of the week he had gathered 8,000 armed men. On 20th April, Hoffmann's forces clashed with troops led by Ernst Toller at Dachau in Upper Bavaria. After a brief battle, Hoffmann's army was forced to retreat. (51)

Eugen Levine announced that the German Communist Party had doubts about the proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, but that the party would be in "the forefront of the fight" against any counter-revolutionary attempt and urged the workers to elect "revolutionary shop stewards" in order to defend the revolution. Levine argued that they should "elect men consumed with the fire of revolution, filled with energy and pugnacity, capable of rapid decision-making, while at the same time possessed of a clear view of the real power relations, thus able to choose soberly and cautiously the moment for action." (52)

Paul Frölich pointed out: "From 14 to 22 April there was a general strike, with the workers in the factories ready for any alarm. The Communists sent their feeble forces to the most important points... The administration of the city was carried on by the factory councils. The banks were blocked, each withdrawal being carefully controlled. Socialisation was not only decreed, but carried through from below in the enterprises." (53)

Hoffmann's spies were providing him with worrying reports about what was taking place in Bavaria: "Time and again one could hear in the discussions in the streets that Bavaria was called upon to promote the world revolution... These speakers were often quite reasonable people... It would be a fateful error if it were assumed that in Munich the same clear division between Spartakists and other socialists exists as for example in Berlin. For the present policy of the Communists aims constantly at uniting the whole working class against capitalism and in favour of world revolution." (54)

Johannes Hoffmann reacted by arranging for posters to appear all over Munich that proclaimed: "The Russian terror rages in Munich unleashed by alien elements. This shame must not endure for another day, another hour... Men of the Bavarian mountains, plateaux and woods, rise like one man... Head for the recruiting depots. Signed Hoffmann, Schneppenhorst." (55)

Eugen Levine pointed out that Colonel Franz Epp posed a serious threat to the revolution: "Colonel Epp is already recruiting volunteers. Students and other bourgeois youths are flocking to him from all sides. Nuremberg declared war on Munich. The gentlemen in Weimar recognise only Hoffmann's government. Noske is already whetting his butcher's knife, eager to rescue his threatened party friends and the threatened capitalists." (56)

Some of the revolutionaries realised that it was not possible to create a successful Bavarian Soviet Republic. Paul Frölich argued: "Bavaria is not economically self-sufficient. Its industries are extremely backward and the predominant agrarian population, while a factor in favour of the counter-revolution, cannot at all be viewed as pro-revolutionary. A Soviet Republic without areas of large scale industry and coalfields is impossible in Germany. Moreover the Bavarian proletariat is only in a few giant industrial plants genuinely disposed towards revolution and unhampered by petty bourgeois traditions, illusions and weaknesses." (57)

Rosa Levine-Meyer pointed out: "The streets were filled with workers, armed and unarmed, who marched by in detachments or stood reading the proclamations. Lorries loaded with armed workers raced through the town, often greeted with jubilant cheers. The bourgeoisie had disappeared completely; the trams were not running. All cars had been confiscated and were being used exclusively for official purposes. Thus every car that whirled past became a symbol, reminding people of the great changes. Aeroplanes appeared over the town and thousands of leaflets fluttered through the air in which the Hoffmann government pictured the horrors of Bolshevik rule and praised the democratic government who would bring peace, order and bread." (58)

Munich suffered terrible food shortages. The Red Guards sent out food patrols and did manage to steal a certain amount from the rich, but it was not enough to feed the soldiers, let alone the mass of workers. "Efforts to get more food for the poorest could lead only to clashes with the lower middle classes, which the counter-revolution was only too happy to exploit. By the end of the second week resentment began to build up even among the most radical sections of workers." (59)

On 10th April Ernst Toller made an attack on the leaders of the German Communist Party in Munich that had established the Second Bavarian Soviet Republic. He also accused Eugen Levine and Max Levien of having "absconded with the funds of the crippled war-veterans". (60) A few days later he argued: "I consider the present government a disaster for the Bavarian toiling masses. To support them would in my view compromise the revolution and the Soviet Republic." (61)

On the night of 29th April, ten prisoners, members of the Thule Society, an early fascist group, whose membership included Rudolf Hess, who had been accused of counter-revolutionary activity, were executed in the cellar of the Luitpold College. None of the Communist leaders were at that time in the building. According to Rosa Levine-Meyer this incident "unleashed tales of cut off fingers, put out eyes: the entire vocabulary of wartime atrocity came back to life... the fury within and outside the town reached its pitch." (62)

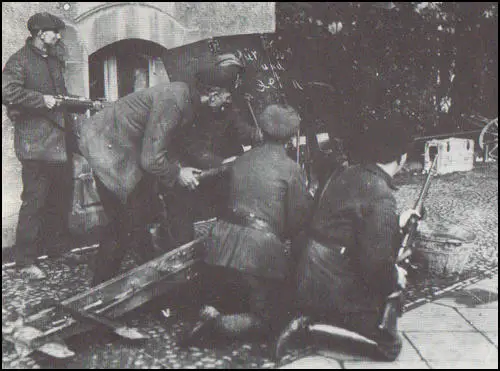

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly." (63)

The Freikorps entered Munich on 1st May, 1919. Over the next two days the Freikorps easily defeated the Red Guards. Gustav Landauer was one of the leaders who was captured during the first day of fighting. Rudolf Rocker explained what happened next: "Together with other prisoners he was loaded on a truck and taken to the jail in Starnberg. From there he and some others were driven to Stadelheim a day later. On the way he was horribly mistreated by dehumanized military pawns on the orders of their superiors. One of them, Freiherr von Gagern, hit Landauer over the head with a whip handle. This was the signal to kill the defenseless victim.... He was literally kicked to death. When he still showed signs of life, one of the callous torturers shot a bullet in his head. This was the gruesome end of Gustav Landauer - one of Germany's greatest spirits and finest men." (64)

Allan Mitchell, the author of Revolution in Bavaria (1965), pointed out: "Resistance was quickly and ruthlessly broken. Men found carrying guns were shot without trial and often without question. The irresponsible brutality of the Freikorps continued sporadically over the next few days as political prisoners were taken, beaten and sometimes executed." An estimated 700 men and women were captured and executed. (65)

Toller, who served as President of the Bavarian Soviet Republic between 6th and 12th April and was expected to be found guilty and sentenced to death but his friends began an international campaign to save his life. Max Weber, Thomas Mann and Max Halbe, gave evidence on his behalf in court. Wolfgang Heine, a leading figure in the Social Democratic Party and the Prussian Minister of the Interior, wrote to the court that he could "say nothing but good about Toller's character", calling him "an incorrigible optimist... who rejects all violence" and concluding that "his execution could have only the most unfortunate consequences". (66)

Ernst Toller was arrested and charged with high treason. At his trial Toller argued: "We revolutionaries acknowledge the right to revolution when we see that the situation is no longer tolerable, that it has become a frozen. Then we have the right to overthrow it. The working class will not halt until socialism has been realized. The revolution is like a vessel filled with the pulsating heartbeat of millions of working people. And the spirit of revolution will not die while the hearts of these workers continue to beat. Gentlemen! I am convinced that, by your own lights, you will pronounce judgement to the best of your knowledge and belief. But knowing my views you must also accept that I shall regard your verdict as the expression, not of justice, but of power." (67)

Although Toller was found guilty of high treason, the judge acknowledged his "honourable motives" and sentenced him to only five years in prison. The trial had made him a hero of the left and his play, The Transformation was produced at the Der Tribune Theatre, in Berlin on 30th September 1919, running for well over a hundred performances and attracting the enthusiasm of audiences and critics alike. Alfred Kerr, the most important theatre critic in Germany, hailed it as the victory of the "theatre of Suggestion" over the "theatre of illusion". The success of the production established Toller's fame as a dramatist. (68)

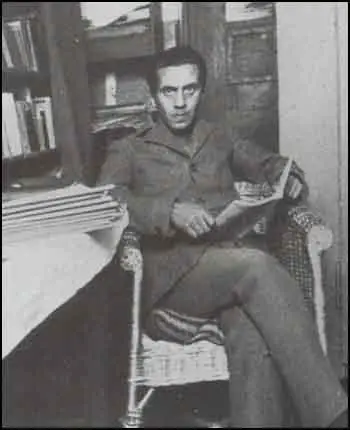

Life in Prison

Ernst Toller hated the impersonal and routine of prison life. He told his friend, Netty Katzenstein: "It is dreadful to be exposed day after day to the monotonous, repetitive noises of this place, where the walls are so thin you can hear every noise from the cells above, below and on either side of you. Noise in the corridors, the rattling of keys, slamming of the iron doors, warders calling the roll, hob-nailed boots stamping on the stone floors, or worse still, the shuffling of rubber soles." (69)

After spending six months in prison the government offered Toller a pardon. He refused saying he should not be free when others were not. (70) "The Bavarian Minister of Justice wanted to make a grand gesture and set me free. I refused; to have accepted would have meant supporting the hypocrisy of the Government; besides I stuck at the idea of being freed while others remained behind in prison." However, life was extremely difficult in prison and "sometimes I deeply regretted having refused the offer of a pardon that was extended to me in 1919 after six months in prison." (71)

The authorities made life difficult for Toller. During his time in prison he spent a total of 149 days in solitary confinement, 243 days deprived of writing materials and 24 days without food. Censorship made letter-writing a burden. He told Romain Rolland: "You become a tightrope walker of the word. Even as you write, you feel the malicious hand of the censor". (72)

Toller was disappointed when left-wing members of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) left to join the German Communist Party (KPD). The USPD continued until 1922 when it merged with the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Toller rejected the reformism of the SPD and the sectarianism of the KPD. (73) He also disliked the cult of the personality" taking place in the Soviet Union: "To be able to live without idols, that’s one of the decisive things. Idols are the fictions which are supposed to be ‘necessary to life’. To be as devout as those who believe in idols and yet not to need any. None at all. Nonetheless to want, nonetheless to act. Whoever can do that is free." (74)

While in prison Toller wrote a series of plays. It has been suggested that he would never have been a successful dramatist but for his imprisonment. It was definitely the most creatively productive period of his life. However, he found the constant noise in prison made it difficult to concentrate. He admitted to Kurt Wolff that he often felt oppressed by the enforced community of prison life: "If I have to be in prison, I often wish I could be allowed to live much more alone." (75) Toller's most creative time was at night, but prison regulations did not permit prisoners to use artificial light, so that he was often forced to drape a blanket over his table and creep under it to write by the light of a hidden candle. (76)

Masses and Man

The first play he wrote in the Eichstätt Prison was Masses and Man. In the months following the defeat of the revolution in Bavaria, he had been troubled by feelings of guilt and remorse which had almost overwhelmed him. He completed the play in a single creative burst of three days, without any preliminary drafts. Toller told his friend, Theodor Lessing: "After experiences the force of which a man can perhaps stand only once without breaking, Masses and Man was a liberation from spiritual anguish." (77)

Toller explained to another friend, Netty Katzenstein, that his experience of revolution had confronted him with the conflict between revolutionary ends and means, between moral principal and political expediency. He now saw this conflict as inevitable and the situation of the revolutionary himself as inherently tragic. "The ethical man: living solely according to his own principles. The political man: fighter for social forms which are the prerequisite of a better life for others. Fighter, even if he violates his own principles. If the ethical man becomes a political man, what tragic road is spared him?" (78)

Toller wrote the play in a a few days: "The lights were turned out every evening at nine o'clock, and we were not allowed candles; so I lay on the floor under the table and hung a cloth over it to conceal the light of my candle. All night until morning I wrote in that way." In his autobiography he explained why he selected this subject: "The masses, it seemed, were impelled by hunger and want rather than by ideals. Would they still be able to conquer if they renounced force for the sake of an ideal?... It was this conflict that inspired my play Masses and Men. I was so oppressed by the problem, it so harassed and bewildered me, that I had to get it out of my system, to clarify the conflict by the dramatic presentation of all the issues involved." (79)

The play's protagonist, the Woman, calls for revolution, but believes it can be achieved through the non-violent means of the mass-strike. She is opposed by the Nameless One, who declares that only revolutionary force can free the masses from oppression. The dramatic conflict consists in the clash between their two points of view. It has been claimed that what Toller is presenting is essentially the clash between himself and Eugen Levine, and therefore also between Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) and German Communist Party (KPD).

Masses and Man had a remarkable reception when it was first put on by the Municipal Theatre at Nuremberg. Some critics said it was pure Bolshevism whereas others saw it as counter-revolutionary. "Some critics also accused the play of tendentiousness; but what would not have been tendentious in their eyes? Only a play which implied whole-hearted acceptance of the existing order. There is only one form of tendentious which the artist must avoid, and that is to make the issue simply between good and evil, black and white. The artist's business is not to prove theses (a theory) but to throw light upon human conduct. Many great works of art have also a political significance; but these must never be confused with mere political propaganda in the guise of art. Such propaganda is designed exclusively to serve an immediate end, and is at the same time something more and something less than art. Something more because, at its best, it may possibly stimulate the public to immediate action; something less because it can never achieve the profundity of art, can never awaken in us the tragic sense of life... Art is its greatest, purest manifestations is always timeless; but the poet who wishes to reach the heights and penetrate the depths must take care to specify particular heights and particular depths, or he will never catch the public ear, and will remain incomprehensible to his own generation." The play was eventually banned by the government after a complaint from the German-Jewish Citizen's Union which took offence at the scene in the Stock Exchange that they believed was anti-semitic. (80)

The Machine Wreckers

Toller's efforts to place his experience into an historical framework dictated the choice of historical subject-matter for his next play, The Machine Wreckers, that was written in the winter of 1920-1921. It was based on events that took place in England during the early days of the Industrial Revolution. In the early months of 1811 the first threatening letters from General Ned Ludd and the Army of Redressers, were sent to employers in Nottingham. Workers, upset by wage reductions and the use of unapprenticed workmen, began to break into factories at night to destroy the new machines that the employers were using. In a three-week period over two hundred stocking frames were destroyed. In March, 1811, several attacks were taking place every night and the Nottingham authorities had to enroll four hundred special constables to protect the factories. To help catch the culprits, the Prince Regent offered £50 to anyone "giving information on any person or persons wickedly breaking the frames". These men became known as Luddites. (81)

In February 1812 the government of Spencer Perceval proposed that machine-breaking should become a capital offence. Lord Byron made a speech in the House of Lords on the subject of machine-breaking. "During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the the county I was informed that forty Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection.... But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community.... As the sword is the worst argument than can be used, so should it be the last. In this instance it has been the first; but providentially as yet only in the scabbard. The present measure will, indeed, pluck it from the sheath; yet had proper meetings been held in the earlier stages of these riots, had the grievances of these men and their masters (for they also had their grievances) been fairly weighed and justly examined, I do think that means might have been devised to restore these workmen to their avocations, and tranquility to the country." (82)

Despite the warnings made by Byron, Parliament passed the Frame Breaking Act that enabled people convicted of machine-breaking to be sentenced to death. As a further precaution, the government ordered 12,000 troops into the areas where the Luddites were active. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) suggested that "masses of workers were coming to realise as the result of ferocious class legislation... that the state apparatus was in the hands of their oppressors." (83)

In Toller's play, Jimmy Cobbett, a politically conscious workman, returns to his native Nottingham to find the weavers on strike against the introduction of new machinery by the factory owner, Ure. He also discovers that his brother Henry has worked his way up to become the manager of the factory. John Wible, the leader of the strikers, is a Luddite, and wants the workers to destroy the new machines. Cobbett addressed the workers and attempted to persuade them their enemy is not the machine, but the economic system which exploits it. (84)

Cobbett told the weavers: "There is a dream within you! A dream of a wondrous world... a world of justice... a world of justice... a world of communities united in labour... of people united in labour... Brothers join together... If you will the community of all workers, you can achieve it." (85) Instead of destroying machines he urges them to work for political change through the nationwide trade union which is now being formed. Wible urges the workers to destroy the machines. When Cobbett attempts to stop them, Wible incites the mob to kill Cobbett as a traitor. After the killing, the workers realise they have attacked the wrong enemy. (86)

Toller had been reading books on the history of socialism in Britain. This included books by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Max Beer. He found Engels' book, Condition of the Working Class in England (1844). During his research he became interested in the Luddite Revolt as he saw it as an early example of concerted working-class action that resulted in a historical turning-point. He told the German historian, Gustav Mayer, that he had consciously set out to write "the drama of a social class" and the real protagonist of his play was the "weavers". (87)

Hinkemann

Toller's next play was Hinkemann. In his autobiography, I Was a German (1933) Toller pointed out that while writing the play he had the opportunity to escape with a friend. They decided it would be possible if they pretended they wanted to visit the dentist: "I was in the middle of the third act; I intended to write the final scene early the following morning. I had built it up in my mind; I saw every detail vividly; tomorrow I would be able to do it. I knew it. Tomorrow or not at all. I daren't leave it; I daren't interrupt it. I couldn't sleep: should I escape or should I write my play? I chose my play, and my friend went to the dentist without me and escaped quite easily. That day the Minister of Justice forbade further visits to the dentist." (88)

Hinkemann has been cruelly emasculated during the First World War. His wife, Grete, leaves him and begins a relationship with Grosshahn, a womaniser, to whom she confides the secret of Hinkemann's impotence. Desperate for work, Hinkemann finds a job as a fairground strongman, where he has to suck the blood of live rats to amuse a bloodthirsty and degenerate public. In a chance visit to the fair with Grosshahn, Grete sees Hinkemann performing and realising how much he loves her, she breaks off her relationship with Grosshahn. He is angry about this and tells Hinkemann's friends of his impotence. They react by laughing at Hinkemann. (89)

Hinkemann rounds on them, bitterly denouncing their cruelty: "You fools! What do you know about the suffering of a poor miserable creature? How you'd have to change before you could build a new world. You fight the bourgeoisie and yet you are just as puffed up, just as self-righteous, just as uncaring. Each of you hates the other because he's in a different party and swears by a different programme. None of you trusts the next man, none of you even trusts himself." (90)

This incident causes Hinkemann to suffer from depression and this drives Grete to suicide. At the end of the play Hinkemann prepares to hang himself. Hinkemann says: "I don't have the strength to go on. The strength to struggle, the strength to dream. A man who has no strength to dream has lost the strength to live. All seeing becomes knowing, all knowing suffering... I don't want to go on." (91)

When Hinkemann was performed at the Dresden State Theatre on 17th January, 1924, there was a riot. "It was instigated by a National Socialist manufacturer who appropriated the funds of a welfare club and bought eight hundred tickets, which he distributed among students, clerks, and schoolboys. Each of the eight hundred was given a paper with the anti-war sentences from my play on it, which were to be signals for general uproar. The first scene came to an end and the eight hundred stared at each other in dismay; their cue was missing; the producer had cut it. But in the second scene their chance came and there was no holding them; they yelled and whistled and bawled the national anthem." (92)

Attempts by the director and the cast to calm the audience only succeeded in inciting it still further. The police showed uncharacteristic restraint, contenting themselves with removing a few ring-leaders and taking their names and addresses before allowing them to return to their seats. Eventually there was a trial of seven nationalists for their part in the disturbances. The judge acquitted them, ruling that the play constituted an affront to their patriotic feelings and their personal honour, and that they had therefore acted in self-defence. (93)

It has been argued that this play reflected the deep state of despair Toller was felling during this period. He told Netty Katzenstein that after reading Max Beer's, General History of Socialism (1920) he came to the conclusion: "The same struggles repeated, the same ideas, the same clash between ideal and reality, the same heroism, the same blind alleys, the same confusion between the needs of the masses and those of the intellectuals... from revolution to reaction, from reaction to revolution, the same cycle. What for? Where to? I have a deep, deep homesickness and the home is called: Nothingness." (94)

The Swallow Book

In 1923 Toller wrote the lyric cycle that became known as The Swallow Book. It was inspired by the swallows which nested in Toller's cell in 1922. "In the spring a pair of swallows nested in my cell; they lived with me all the summer. The nest was built, and the female brooded on her eggs while the male sang his little twittering song to her. The eggs were hatched and the peasants fed their young and taught them to fly, until one day they flew away and did not come back. The parents had a second brood, but a premature frost killed the young, and they huddled close together silently mourning their dead children. With the coming of autumn they flew away to the southern sun." (95)

At this time Toller was contemplating suicide. However, the song of the swallows, a token of the coming spring and hence of the renewal and regeneration which are both the cause and the object of revolution. "The swallows symbolize freedom in an environment of repression." (96) The opening poem is about August Hagemeister, a fellow member of the Independent Social Democratic Party who had been sentenced to ten years in prison for his role in the German Revolution. He died on 16th January, 1923, through lack of proper medical attention. His death emphasizes the monotony and isolation of imprisonment. "Everywhere you see iron bars. Even the child playing in the distant, oh, so distant field, blooming with lupins, is forced within the bars that divide your eyes." (97)

The Swallow Book The manuscript became the object of a long and bitter dispute between Toller and the prison authorities. Some parts of the cycle, notably the poem inspired by the death of Hagemeister and that celebrating revolutionary youth, were considered by the prison censor to contain "so many provocative passages that the total effect is agitational... In accordance with Section 22 of the prison regulations, The Swallow Book has been confiscated, since it contains much which, if published, would be detrimental to prison discipline." (98)

Toller had made a copy of his work and he had it smuggled out of prison and The Swallow Book was published in 1924. The authorities were furious and moved Toller from his east-facing cell to one which faced north and which swallows would not frequent. The following April, the birds returned to build their nest in his former cell, but the prison authorities, angered by the publication of the book ordered the nest to be destroyed. The swallows built their nest again - and again it was destroyed. (99)

According to Toller: "The swallows, bewildered and passionately eager, began to build three nests simultaneously in three different cells. But they were only half finished when the warders discovered them and repeated the outrage... The struggle lasted for seven weeks; a glorious and heroic struggle between the united forces of Bavarian law and order and two tiny birds. After the nests were torn down for the last time some days went by without a new nest being discovered; evidently the swallows had given up. But soon whispers were going round among the prisoners that the swallows had found a new place in the wash-house behind the overflow pipes where nobody would find them - neither the spying warders without, nor the spying warders within. Rarely had we experienced a purer happiness. The swallows had won after all in their fight against human beastliness. Their victory was ours too." (100)

The Weimar Republic

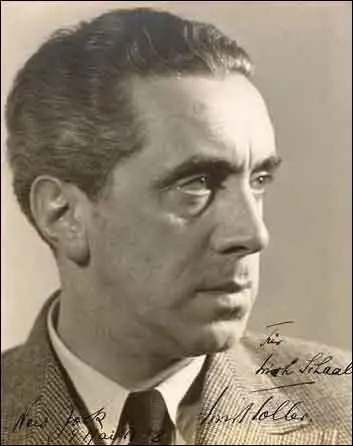

Ernst Toller was released in 1924. He had entered prison as a promising young writer and by the time he left he had become the most famous German dramatist of his generation and his plays had been performed all over the world. Although he did not join a political party he was a leading member of the Group of Revolutionary Pacifists. He argued: "All true pacifism is revolutionary. Pacifism which believes it can pacify the world on the foundation of the capitalism is blind. We must fight this dangerous blindness." (101)

In 1926 Toller visited the Soviet Union and wrote about it in Russian Travel Sketches (1926). He became concerned about what he considered to worship of Lenin, the former leader of the country: "In Russian universities the most important subject is Leninism… A cult always has a crippling effect on individual responsibility, the development of one's own faculties, its adherents believing that what must be recognized and done has already been recognized and done by their idol… We should not underestimate the danger that socialist teachings may become articles of faith which are accepted without thinking, as the Catholic accepts his dogma, especially if it also brings a few State benefits." (102)

Toller was also an active member of the League for Human Rights and became a familiar figure at international meetings and conferences, addressing the Anti-Imperialist Congress in Brussels in 1927, the Congress of the World League for Sexual Reform in Vienna in 1930, the International PEN Congresses in Warsaw (1930) and Budapest (1932) and the Amsterdam Peace Conference of 1932 at which the League against War and Fascism was formed. (103)

Some members of the left attacked Toller's pacifism: "Toller... stagnated in a sentimental humanistic pathos. Pathos was the most widespread manifestation of German pacifism in its variegated species. Where revolutionary clarity of goal and resoluteness were the most burning questions of the day, only humanitarian-pacifist vagueness emerged. In those brief democratic-pacifist years of the republic, one could speak for a time in Germany of an Ernst Toller fashion, under whose influence stood the social-democratic pacifist youth in particular. The ideology of this youth was the pacific faith in humanity and its slogan read: “Never again war!” But of all the hopeless illusions, none was more gruesomely destroyed than this particular one." (104)

Roland-Holst at the League against Imperialism conference at Brussels (February, 1927)

After leaving prison Toller wrote Hoppla, Such is Life (1927) which was directed by Erwin Piscator at the Theatre am Nollendorfplatz. (105) Piscator was not too happy with the first draft of the play as he found it too lyrical and subjective for a documentary exposition of social reality. "All our efforts in the subsequent course of the work were directed towards providing the play with a realistic substructure." (106) Piscator proposed a number of changes which were the subject of lengthy and sometimes heated discussions. He recalled that there were arguments that sometimes turned into heated discussion. (107)

Eventually, Piscator persuaded Toller to rewrite most of the play. Piscator later recalled: "Toller scarcely ever left my apartment. He had made himself at home at my desk and filled page after page at incredible speed with his huge handwriting, consigning the sheets to the wastepaper basket with equal rapidity. And all the while he kept lighting my most expensive cigars and stubbing them out again in the ashtray after a few drags." (108)

The production is one of the landmarks of the early Epic Theater. "Toller’s dissection of political conspiracies, failed revolution, feminist emancipation and class solidarity suggests one answer: it is only in the constant struggle against power that we are alive." What impressed critics and audiences alike was not so much the writing and acting as the use of film, set and sound effects. The play was interrupted with film interludes or illustrations projected on the tall screen in the middle of the stage. The film had been made, on a script written by Toller, using newsreel material and specially shot scenes with the actors. (109) The theatre critic, Herbert Ihering, claimed that "an amazing technical imagination has worked miracles". (110)

At the end of the first performance - which lasted four hours - a section of the audience rose to sing the Internationale. One critic wrote that Piscator had extended the boundaries of theatre, another that he, just as much as Toller, deserved to be called the author of the evening. Some critics suggested that Piscator's production had saved a rather mediocre play. Stefan Großmann, one of Germany's leading critics, commented that it was a triumph for Piscator: "A master of the theatre now has his home. He will allow neither supporters nor authors to distract him." (111)

Erich Mühsam wrote in support of Piscator: "Agitational art is good and necessary. It is needed by the proletariat both in revolutionary times and in the present. But it has to be art, skilled, spirited, and glittering. All arts have agitational potential, but none more than drama, In the theatre, living people present living passion. Here, more than anywhere else, true art can communicate true conviction. Here, the idea of a revolutionary worker can be materialized.... Arts must inspire people, and inspiration comes from the spirit. It is not our task to teach the minds of the workers with the help of the arts - it is our task to bring spirit to the minds of the workers with the help of the arts, as the spirit of the arts knows no limits. Neither dialectics nor historical materialism have anything to do with this; the only art that can enthuse and enflame the proletariat is the one that derives its richness and its fire from the spirit of freedom." (112)

Juliet Jacques has recently written: " It may seem that those of us fighting a resurgent, transnational far-right cannot learn much from the ironic fatalism of Hurrah, We’re Alive! However, Toller’s fearlessness, first in throwing himself into revolutionary politics, and then in using his art to illuminate the murky complexities of its fallout, can inspire contemporary writers. As our own time rapidly approaches the chaos of the 1920s, it is imperative that we use creative work to call people to action, reaching individuals where theory, or political propaganda, might not." (113)

Other plays by Toller included Once a Bourgeois Always a Bourgeois (1928), Draw the Fires (1930), Miracle in America (1931) and the Blind Goddess (1932). Toller traveled the country making speeches on his ideas. Günther Weisenborn, was a young medical student when he first heard Toller speak: "He speaks clearly, still controlled, with quiet outrage, with a nervous elegance which vibrates through all his movements. And then he suddenly bursts forth, hurling a raging denunciation of war and all its works... Ernst Toller transforms the old unspoken yearnings of the workers into words, and in the heat of his tongue the words become a springboard for the rage of the exploited... He is shaken by flaming hatred, of war and the war-mongers. He is in tears, he is moved and his emotion moves the masses." (114)

Ernst Toller was one of the first people in Germany to see the dangers of fascism. In 1927 he warned: "Fascism is such a danger for the European working-class that I believe we should welcome any offensive against it." (115) In February 1929, speaking on the tenth anniversary of the death of Kurt Eisner, he predicted: "A period of reactionary rule lies ahead. Let no one believe that a period of fascism, however moderate, however insidious, will be a short transitional period. The revolutionary, socialist and republican energies which it will destroy will take years to rebuild." (116)

As a Jew, socialist, internationalist and pacifist, Toller, represented everything that Hitler hated: "Is blood to be the only test? Does nothing else count at all? I was born and brought up in Germany; I had breathed the air of Germany and its spirit had molded mine; as a German writer I had helped to preserve the purity of the German language. How much of me was German, how much Jewish? I could not have said. All over Europe an infatuated nationalism and ridiculous pride was raging – must I too participate in the madness of this epoch? Wasn't it just this madness that had made me turn Socialist? – my belief that Socialism would eliminate not only class hatreds but also national hatreds? The words, I am proud to be a German or I am proud to be a Jew, sounded ineffably stupid to me. As well say, I am proud to have brown eyes." (117)

Nazi Germany

In 1932 Toller met the fifteen-year-old, Christiane Grautoff, the daughter of a distinguished art historian. She had begun her stage career as a child actress in 1928, in which she attracted the attention of the legendary Max Reinhardt, who engaged her for a new play by Ferdinand Bruckner. Her performance in this play captivated audiences and critics alike. This led to her being recruited by Erich Kästner for his stage production of Emile and the Detectives. This was also a great success and Grautoff became one of the great attractions of the Berlin stage. (118)

In her unpublished autobiography, Grautoff recalled their first meeting: Ernst Toller's eyes were unendingly sad. His flat was small, his study narrow, the window barred." She would learn that Toller could only write in a small room, preferably with a single barred window which simulated the physical conditions of the prison cell in which he had written his greatest stage successes. Toller went to see Grautoff in her latest play. "From then on, Toller and I saw each other frequently... Ernst and I had a very strange relationship. It was completely platonic... We had long conversations about his life, about my life, his thoughts and my thoughts... Very soon, he began to read to me from his unfinished works." (119)

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (120)

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag parliamentary building caught fire. It was reported at ten o'clock when a Berlin resident telephoned the police and said: "The dome of the Reichstag building is burning in brilliant flames." The Berlin Fire Department arrived minutes later and although the main structure was fireproof, the wood-paneled halls and rooms were already burning. (121)

Hermann Göring, who had been at work in the nearby Prussian Ministry of the Interior, was quickly on the scene. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels arrived soon after. So also did Rudolf Diels: "Shortly after my arrival in the burning Reichstag, the National Socialist elite had arrived. On a balcony jutting out of the chamber, Hitler and his trusty followers were assembled." Göring told him: "This is the beginning of the Communist Revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost. There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will not tolerate leniency. Every communist official will be shot where he is found. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will also no longer be leniency for social democrats." (122)

Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". Orders were given for all KPD members of the Reichstag to be arrested. This included Ernst Torgler, the chairman of the KPD. Göring commented that "the record of Communist crimes was already so long and their offence so atrocious that I was in any case resolved to use all the powers at my disposal in order ruthlessly to wipe out this plague". (123)

That night the police attempted to arrest 4,000 people. This included 130 Berlin writers and intellectuals such as Ernst Toller, Bertolt Brecht, Ludwig Renn, Erich Mühsam, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Zweig, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Erwin Piscator, Lion Feuchtwanger, Willi Bredel, Carl von Ossietzky and Kurt Hiller. When they arrived at Toller's flat he was not there. A few days previously he had traveled to Switzerland, where he was to make a series of radio broadcasts. Toller's absence from Germany, probably saved his life as friends such as Mühsam and Ossietzky, who were still in the country, were to die while in custody. (124)

In the spring of 1933, a group of German anti-Nazi writers, held a kind of council of war at Sanary-sur-Mer in France to discuss their plight. This included Toller, Bertolt Brecht, Arnold Zweig, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann and Lion Feuchtwanger. "It was the first of innumerable similar gatherings that followed, all devoted to the earnest and searching examination of the problem of what writers could do to help to bring about the downfall of Hitler." (125)

In a speech on 1st April, 1933, Joseph Goebbels denounced Ernst Toller as a public enemy of the Third Reich. He claimed that he was the typical representative of the Jewish spirit which sought to undermine Nazi Germany. He was especially angry that Toller had written that "the ideal of heroism is the stupidest ideal of all". Goebbels cried rhetorically: "Two million German soldiers rise from the graves of Flanders and Holland and indict the Jew Toller." (126)

In April 1933, the Nazi government published a black list of writers whose works were to be withdrawn from bookshops and libraries. This included the names of Toller, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Bertolt Brecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Lenin, Maxim Gorky, Victor Hugo, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Ernest Hemingway, Helen Keller, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Radclyffe Hall, Oscar Wilde, Aldous Huxley, D. H. Lawrence, H. G. Wells, Heinrich Mann, Isaac Babel, Ilya Ehrenburg, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Ludwig Renn, Thomas Heine, Arnold Zweig, Erich Mühsam, Erwin Piscator, Erich Maria Remarque, Frank Wedekind, Lion Feuchtwanger, Willi Bredel, Carl von Ossietzky, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Joseph Conrad, Anna Seghers and Kurt Hiller.

On 10th May, 1933, their works were publicly burned in ceremonies all over Germany. On the Opernplatz in Berlin, students from Berlin University, led by their new Professor of Political Pedagogy, Alfred Bäumler, and accompanied by the military bands of the SA and SS, burnt 20,000 books, throwing them into the fire to the accompaniment of ritual incantations. Goebbels made the leading speech at the ceremony: "Against decadence and moral corruption, for discipline and decency in family and state, I consign to the flames the works of Heinrich Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Erich Kästner... The era of extreme Jewish intellectualism is now at an end. The breakthrough of the German revolution has again cleared the way on the German path...The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character. It is to this end that we want to educate you. As a young person, to already have the courage to face the pitiless glare, to overcome the fear of death, and to regain respect for death - this is the task of this young generation. And thus you do well in this midnight hour to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past. This is a strong, great and symbolic deed - a deed which should document the following for the world to know - Here the intellectual foundation of the November Republic is sinking to the ground, but from this wreckage the phoenix of a new spirit will triumphantly rise." (127)

To extend their control over the written and spoken word, the Nazis founded the Reich Chamber of Literature, a guild like organisation to which writers and publishers had to belong in order to exercise their profession. Membership was explicitly denied to "non-aryans", to writers classified as "Marxist" and to all those who had expressed their opposition to fascism. All members were required to make a declaration of loyalty to the new regime, a provision intended to ensure that only works which conformed to rigid Nazi criteria could be published in Germany. The journalist, Dorothy Thompson, who witnessed these early days of Nazism, wrote that "practically everybody who in world opinion has stood for what is currently called German culture prior to 1933 is now a refugee." (128)

Georgi Dimitrov, Marinus van der Lubbe, Ernst Torgler, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev were indicted on charges of setting the Reichstag Fire. The trial began on 21st September, 1933. The presiding judge was Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger of the Supreme Court. The accused were charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government. (129) The trial was an attempt to justify the arrest and imprisonment of left-wing artists and political activists. In London it was decided to establish Legal Commission of Inquiry into the Burning of the Reichstag and Toller was invited to testify before it. (130)

The trial was the idea of Willi Münzenberg, but he was refused entry to Britain and so it was organized by Denis Nowell Pritt and other senior members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The hearings took place in the court-room of the Law Society. Toller was only one of a series of well-known witnesses who included Rudolf Brietscheid, Paul Hertz, Wilhelm Koenen, Albert Grzesinski and Georg Bernhard. One of the principal tasks of the organizing committee was to secure the entry of these witnesses into the country in the face of Home Office obstruction. (131)

Toller testified on the final day of the hearings, where he gave evidence on the mass arrests that had taken place under Adolf Hitler: "I do not know what I was to be charged with. There are thousands of people in concentration camps today who do not what they are charged with." Toller declared his belief that the Reichstag Fire was part of a pre-arranged plan and closed his address rhetorically: "I refuse to recognize the right to rule of the present rulers in Germany, for they do not represent the noble sentiments and aspirations of the German people." (132)

Toller decided to remain in Britain. He traveled extensively, where he lectured on the need for the international community to join together in order to resist fascism. He became close friends with journalists, Kingsley Martin, H. N. Brailsford and Henry Wickham Steed. With their help his articles appeared in the Manchester Guardian, the Observer, the New Statesman, Time & Tide and the Spectator. On 28th December, 1933, his mother died in Germany. His sister wrote that his mother had died with his last letter worn in a locket around her neck, like an amulet. (133)

In January 1934 Toller arranged to meet Christiane Grautoff in Switzerland. He had not seen her for over a year. Now aged seventeen, Toller proposed marriage. A few weeks previously, she had been offered a leading role in a Nazi film eulogizing Horst Wessel, but she rejected it as "she did not care to be a party to a theatre whose theme was race hatred". (134) She agreed to his proposal and after performing in a play in Zurich, under the direction of Gustav Hartung, she moved to London and after their marriage in May 1935 they set up home in Hampstead. (135)

Christine was anxious to pursue her acting career and took lessons in English language and diction. However, it was two years before making her London stage debut in Toller's satirical musical comedy, No More Peace. Life with Toller was not easy as since leaving Germany he suffered bouts of depression, during which he would spend days lying in a darkened room. These attacks were closely associated with feelings of creative inadequacy, which made him fear that his creative talent had finally deserted him. His changes of mood were abrupt and startling. Fritz Helmut Landshoff remembered that days of self-imposed isolation would suddenly give way, often in the early hours of the morning, to a compulsive need for company and conversation. (136)