Ernst Torgler

Ernst Torgler was born in Berlin on 25th April 1893. His father worked as a labourer in the local gasworks. His mother was active in politics and was a friend of August Bebel and he grew up as a socialist. He left school at 14 and held a variety of different jobs before becoming an accountant. In 1910 he joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and during the First World War he served in the German Army . (1)

In April, 1917, left-wing members of the SDP, including Karl Liebknecht, Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Emil Barth, Julius Leber, Ernst Toller, Ernst Thälmann, Rudolf Breitscheild, Emil Eichhorn, and Rudolf Hilferding, formed the Independent Socialist Party (USPD).

In 1920 Torgler joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He became a town councillor before being elected to the Reichstag in December 1924. Torgler became deputy chairman of the KPD in 1927 and chairman in 1929. At the time he was described as being "tall, good-looking man in his early forties." (2) Another source claimed that he was "affable and popular". (3) Torgler was considered to be a formidable debater and was known for his "biting sarcasm and his criticism of the tyranny of fascism." (4)

Ernst Torgler & Adolf Hitler

In January, 1933, Adolf Hitler, became Chancellor of Germany. Attempts were made to form a united front alliance between the SDP and KPD. Torgler rejected the idea as he believed that after the Nazi Party assumed power in "four weeks the whole working class will be united under the leadership of the Communist Party". (5)

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary on 31st January, 1933, about the plans to deal with the KPD: "During discussions with the Führer we drew up the plans of battle against the red terror. For the time being, we decided against any direct countermeasures. The Bolshevik rebellion must first of all flare up; only then shall we hit back." (6)

The Gestapo raided Communist headquarters on 24th February, 1933. Hermann Göring claimed that he had found "barrels of incriminating material concerning plans for a world revolution". (7) However, the alleged subversive documents were never published and it is assumed that in reality the Nazi government had not discovered anything of any importance. (8)

The Reichstag Fire

On 27th February, 1933, the Reichstag caught fire. It was reported at ten o'clock when a Berlin resident telephoned the police and said: "The dome of the Reichstag building is burning in brilliant flames." The Berlin Fire Department arrived minutes later and although the main structure was fireproof, the wood-paneled halls and rooms were already burning. (9)

Göring, who had been at work in the nearby Prussian Ministry of the Interior, was quickly on the scene. Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels arrived soon after. So also did Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo: "Shortly after my arrival in the burning Reichstag, the National Socialist elite had arrived. On a balcony jutting out of the chamber, Hitler and his trusty followers were assembled." Göring told him: "This is the beginning of the Communist Revolt, they will start their attack now! Not a moment must be lost. There will be no mercy now. Anyone who stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will not tolerate leniency. Every communist official will be shot where he is found. Everybody in league with the Communists must be arrested. There will also no longer be leniency for social democrats." (10)

Marinus van der Lubbe was arrested in the building. He was a 24 year-old vagrant and was a former member of the Communist Party of the Netherlands. (11) Van der Lubbe was immediately interviewed by the Gestapo. According to Rudolf Diels: "A few of my department were already engaged in interrogating Marinus Van der Lubbe. Naked from the waist upwards, smeared with dirt and sweating, he sat in front of them, breathing heavily. He panted as if he had completed a tremendous task. There was a wild triumphant gleam in the burning eyes of his pale, haggard young face." (12)

Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". Orders were given for all KPD members of the Reichstag to be arrested. Torgler heard on the radio that he was thought to be one of those who had set fire to the building. After a number of telephone conversations, Torgler decided to report to the police. "He knew that he would have no difficulty in proving his complete innocence." (13)

Ernst Torgler was arrested and was interviewed by the Gestapo. He was able to give details of having left the Reichstag building at 8.15 p.m. and arriving at the Aschinger Restaurant at 8.30 p.m. Witnesses confirmed this but his alibi was rejected and he was placed in custody and for the next seven months he was "fettered day and night". (14) Torgler complained: "It was left to the warders' discretion either to tighten our chains until the blood circulation was gravely impeded, and the skin broke, or else to take pity on us and to loosen the chains by one notch." (15)

Hermann Göring insisted that Torgler should not be released as he was convinced that he was responsible for planning the fire: "The record of Communist crimes was already so long and their offence so atrocious that I was in any case resolved to use all the powers at my disposal in order ruthlessly to wipe out this plague". (16)

According to Detective-Inspector Walter Zirpins, who was given the task of investigating the fire, "three eye-witnesses saw van der Lubbe in the company of Torgler... before the fire. In view of van der Lubbe's striking appearance, it is impossible for all three to have been wrong." As a result Torgler was charged with being involved in the Reichstag Fire. (17)

While in prison awaiting trial Torgler was supplied with information that suggested that Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Ernst Röhm, were involved in starting the fire. He refused to believe the story: "Van der Lubbe and old acquaintance of Röhm and on his list of catamites? Could Goebbels really have planned the fire, and could Göring, standing, as it were, at the entrance of the underground tunnel, really have supervised the whole thing?" (18)

Kurt Rosenfeld, had been Torgler's lawyer for many years. However, like other socialists and communists in Germany, fled the country when the Nazi government began arresting left-wing opponents of the regime and sending them to concentration camps. In August 1933, Torgler was forced to employ a lawyer, Alfons Sack, who was a member of the Nazi Party. (19)

Sack hesitated about defending Torgler as he was aware that if he did a good job, and his client was found not guilty, he faced the possibility of imprisonment. "I was concerned with only one question: is the man guilty or is he innocent? Only if I could be reasonably certain that Torgler had entered politics for idealistic reasons and not for selfish motives and that he had never made personal capital out of his political beliefs, would I find it within me to accept his defence." Sack eventually came to the conclusion that Torgler was telling the truth. (20)

Reichstag Fire Trial

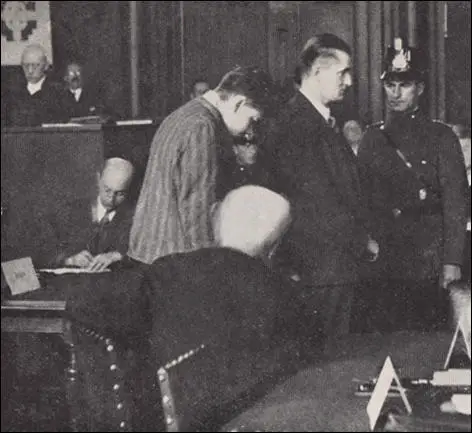

Ernst Torgler, Marinus van der Lubbe, Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev, were indicted on charges of setting the Reichstag on fire. The trial began on 21st September, 1933. The presiding judge was Judge Dr. Wilhelm Bürger of the Supreme Court. The accused were charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government. (21)

Douglas Reed, a journalist working for The Times, described the defendants in court. "A being (Marinus van der Lubbe) of almost imbecile appearance, with a shock of tousled hair hanging far over his eyes, clad in the hideous dungarees of the convicted criminal, with chains around his waist and wrists, shambling with sunken head between his custodians - the incendiary taken in the act. Four men in decent civilian clothes, with intelligence written on every line of their features, who gazed somberly but levelly at their fellow men across the wooden railing which symbolized the great gulf fixed between captivity and freedom.... Torgler, last seen by many of those present railing at the Nazis from the tribune of the Reichstag, bore the marks of great suffering on his fine and sensitive face. Dimitrov, whose quality the Court had yet to learn, took his place as a free man among free men; there was nothing downcast in his bold and even defiant air. Little Tanev had not long since attempted suicide, and his appearance still showed what he had been through, Popov, as ever, was quiet and introspective." (22)

On the opening day of the trial Torgler received a message from Wilhelm Pieck, the leader of the German Communist Party (KPD) in exile. It said that he was to take the first opportunity to "disown Dr. Sack as an agent of Hitler". He was also told to state in court that Hermann Göring and Joseph Goebbels had set the Reichstag on fire. "I argued with myself for at least twenty-four hours. If I compiled, I would cause a sensation and that would make an extremely good headline. But what would happen to me?" Torgler concluded that if he did this he was "signing his own death warrant" and decided to allow Sack to defend him in court. (23)

The main witness against Torgler was Gustav Lebermann, who was at the time serving a prison sentence for theft and fraud. In court he alleged that he had first met Torgler in Hamburg on 25th October 1931. He was told to prepare for a "big job" in the future. On 6th March, 1933, Torgler offered him 14,000 marks, if he set fire to the Reichstag building. Lebermann claimed that when he refused Torgler punched him in the abdomen.

Torgler told the court: "All I can say regarding this evidence is how astonished I am that anyone should utter such lies before the highest Court of the land. I have never seen this man in my life. I have never been in Hamburg for any length of time, and when I did go to Hamburg it was merely to attend meetings of the Union of Post Office Workers... Not a single word the witness has spoken is true. Everything he says is a lie, from start to finish." (24)

Berthold Karwahne, Stefan Kroyer and Kurt Frey all testified that they saw Torgler with Marinus van der Lubbe. However, they were all senior officials in the Nazi Party and very few people believed their stories. Torgler, claimed that the man they thought was Van der Lubbe, was a journalist, Walther Oehme. When he was interviewed by the Gestapo, he denied that he met Torgler at the time. However, on the 28th October, he testified that he had been wrong and had in fact, been with Torgler at the time he had originally stated. This incensed the Public Prosecutor, who realised that the court was now unlikely to convict him. (25)

On 23rd December, 1933, Judge Wilhelm Bürger announced that Marinus van der Lubbe was guilty of "arson and with attempting to overthrow the government". Bürger concluded that the German Communist Party (KPD) had indeed planned the fire in order to start a revolution, but the evidence against Ernst Torgler, Georgi Dimitrov, Blagoi Popov and Vassili Tanev, was insufficient to justify a conviction. (26)

Ernst Torgler in Nazi Germany

The Nazi daily newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter, condemned the verdict as a miscarriage of justice "that demonstrates the need for a thoroughgoing reform of our legal life, which in many ways still moves along the outmoded liberalistic thought that is foreign to the people". (27)

Adolf Hitler was furious that the rest of the defendants were acquitted and he decided that in future all treason cases were taken from the Supreme Court and given to a new People's Court, set up on 24th April 1934, where prisoners were judged by members of the Nazi Party. It was also announced that Ernst Thalmann, the leader of the KPD, had been charged with planning a revolutionary uprising. (28)

Ernst Torgler was placed into "protective custody" by the police. The KPD leadership in exile stripped Torgler of his party membership for refusing to follow party orders in the way he behaved in court. His lawyer, Alfons Sack, was also imprisoned and according to Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo "he was kept behind bars for some considerable time, ostensibly so that he could 'adjust' his views." (29)

Torgler argued that after being expelled from the KPD he felt he was "without friends". In June 1940, Torgler began working for the Nazi Propaganda Ministry. In 1941, Torgler worked in Czechoslovakia on the staff of Reinhard Heydrich. Torgler was suspected of being involved in the July Plot, when an attempt was made to assassinate Adolf Hitler. However, he was not arrested and in 1945 he was an administrator in Poland. (30)

After the war Torgler attempted to rejoin the German Communist Party (KPD) but his application was rejected and he became a member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

Ernst Torgler died on 19th January 1963.

Primary Sources

(1) Douglas Reed, The Burning of the Reichstag (1934)

A being (Marinus van der Lubbe) of almost imbecile appearance, with a shock of tousled hair hanging far over his eyes, clad in the hideous dungarees of the convicted criminal, with chains around his waist and wrists, shambling with sunken head between his custodians - the incendiary taken in the act. Four men in decent civilian clothes, with intelligence written on every line of their features, who gazed sombrely but levelly at their fellow men across the wooden railing which symbolized the great gulf fixed between captivity and freedom.... Torgler, last seen by many of those present railing at the Nazis from the tribune of the Reichstag, bore the marks of great suffering on his fine and sensitive face. Dimitrov, whose quality the Court had yet to learn, took his place as a free man among free men; there was nothing downcast in his bold and even defiant air. Little Tanev had not long since attempted suicide, and his appearance still showed what he had been through, Popov, as ever, was quiet and introspective.

(2) Alfons Sack, The Reichstag Fire Process (1934)

I was concerned with only one question: is the man guilty or is he innocent? Only if I could be reasonably certain that Torgler had entered politics for idealistic reasons and not for selfish motives and that he had never made personal capital out of his political beliefs, would I find it within me to accept his defence.

(3) Ernst Torgler, Die Zeit (4th November, 1948)

The message said: "The Central Committee asks you to take the first opportunity to disown Dr. Sack as an agent of Hitler". Added was a rather stilted paragraph instructing me to tell the Court that Goebbels and Göring had set the Reichstag on fire. The thing was signed by Wilhelm Pieck. I argued with myself for at least twenty-four hours. If I compiled, I would cause a sensation and that would make an extremely good headline. But what would happen to me?

I had fallen between two stools: Fascism and Bolshevism... If I really told the Court that Göring and Goebbels had set the Reichstag on fire - without being able to produce a shadow of a proof for this allegation - was I not simply signing my own death warrant?

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)