The Munich Agreement

Anthony Eden resigned on 21st February, 1938. Neville Chamberlain now appointed fellow appeaser, Lord Halifax, as his new foreign secretary. Nevile Henderson, the British ambassador in Berlin, told Chamberlain that we would lose a war with Nazi Germany. Hitler's main concern was over Czechoslovakia, a country that had been created after the allied victory in the First World War. Before the conflict it had been part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire. The population consisted of Czechs (51%), Slovaks (16%), Germans (22%), Hungarians (5%) and Rusyns (4%).

Lord Halifax recommended that the British government should apply pressure on President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia to give up the Sudetenland, with its largely German-speaking population, to Germany. Henderson's biographer, Peter Neville, pointed out: "So strong was this conviction that he sometimes erred on the side of prejudice against the Czechs and their president, Beneš". (1)

In March 1938, Adolf Hitler advised Konrad Henlein, the leader of the Sudeten Germans, on his political campaign. Hitler told him "that demands should be made by the Sudeten German Party which are unacceptable to the Czech government." Henlein later summarised the comments: "We must always demand so much that we can never be satisfied." Hitler suggested that once a crisis was established, he would be willing to send German troops into Czechoslovakia. (2)

Later that month, Hugh Christie, an MI6 agent, working in Nazi Germany, told headquarters that Hitler would be ousted by the military if Britain joined forces with Czechoslovakia against Germany. Christie warned that the "crucial question is: How soon will the next step against Czechoslovakia be tried?... The probability is that the delay will not exceed two or three months at most, unless France and England provide the deterrent, for which cooler heads in Germany are praying." (3)

Chamberlain believed his appeasement policy was very popular with the British people. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the highest selling newspaper in Britain told the former Canadian Prime Minister Richard B. Bennett, that Chamberlain was "the best P.M. we've had in half a century... dominating Parliament but the country has not yet taken to him." If he wished, claimed Beaverbrook, he could "be Prime Minister for the rest of his life." Chamberlain told his sister that "as for the House of Commons there can be no question that I have got the confidence of our people as Stanley Baldwin never had it." (4)

However, some members of his cabinet found him a difficult man. Philip Cunliffe-Lister (Lord Swinton), the Secretary of State for Air, criticised Chamberlain as "overly autocratic and intolerant of criticism". He became suspicious to the point of paranoia, employing Sir Joseph Ball, with the support of MI5, to gather information on the contacts and financial arrangements of his political opponents, and even to intercept their telephone calls. (5) Stanley Baldwin complained to Anthony Eden that his own work "in keeping politics national instead of party" had been rendered worthless. Eden replied that Chamberlain was attempting to "return to class warfare in its bitterest form". (6)

The Czech crisis reached the first of many dangerous points in May 1938. It was reported that two Sudeten German motorcyclists had been shot dead by the Czech police. This led to rumours of Hitler preparing to use the incident as a pretext for invasion and there were reports of German troops assembling near the Czech border. The French and Soviet governments pledged support to the Czechs. Lord Halifax sent a message to Berlin which warned that if force was used Germany "could not count upon this country being able to stand aside". At the same time he sent a diplomatic message which told the French they should not assume Britain would fight to save Czechoslovakia. (7)

On 25th May, Lord Halifax had a meeting Tomas Masaryk, the Czechoslovak minister in London, and told him the least that his country could "get away with" would be autonomy on "the Swiss model" combined with neutrality in foreign policy. Later that day Chamberlain told the Cabinet "the Sudeten Deutsch should remain in Czechoslovakia but as contented people." He made the same point that Halifax had made to Masaryk, when he said if Czechoslovakia became a neutral state "it might be possible to get a settlement in Europe." (8) Five days later, Hitler made a speech where he stated: "It is my unalterable decision to smash Czechoslovakia by military action in the near future." (9)

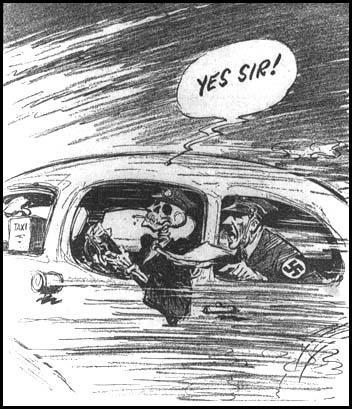

Chicago Times (8th September, 1938)

Winston Churchill now decided to become involved in discussions with representatives of Hitler's government in Nazi Germany in an attempt to avoid conflict between the two nations. In July, 1938, Churchill had a meeting with Albert Forster, the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig. Forster asked Churchill whether German discriminatory legislation against the Jews would prevent an understanding with Britain. Churchill replied that he thought "it was a hindrance and an irritation, but probably not a complete obstacle to a working agreement." (10)

On the suggestion of Lord Halifax it was decided to send Lord Runciman, to Czechoslovakia to investigate the Sudeten claims for self-determination. He arrived in Prague on 4th August 1938, and over the next few days he saw all the major figures involved in the dispute within Czechoslovakia. He became extremely sympathetic to the Sudeten desire for home rule. In his report he placed the major share of the blame for the breakdown of talks on the Czech government and recommended that the Sudeten Germans be allowed the opportunity to join the Third Reich. Neville Henderson supported Runciman and told Chamberlain: "However, badly Germany behaves does not make the rights of the Sudeten any less justifiable." (11)

A group of anti-Nazi Germans, holding high office, including Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Colonel-General Ludwig Beck, and Carl Goerdeler, sent Major Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin to London as their emissary to warn Chamberlain of Hitler's plans to invade Czechoslovakia, and later to attack France and eventually the Soviet Union. Kleist-Schmenzin argued that only a strong Anglo-French line would force Hitler to back down. Chamberlain rejected these views because they conflicted with his own view that open threats of force would hasten the outbreak of war. (12)

The Munich Agreement

On 12th September, 1938, Hitler whipped his supporters into a frenzy at the annual Nuremberg Rally by claiming the Sudeten Germans were "not alone" and would be protected by Nazi Germany. A series of demonstrations took place in the Sudeten area and on 13th September, the Czech government decided to introduce martial law in the area. Konrad Henlein, the leader of the Sudeten Germans, fled to Germany for protection. (13)

Chamberlain now sent Hitler a message requesting an immediate meeting, which was promptly granted. Hitler invited Chamberlain to see him at his home in Berchtesgaden. It would be the first visit by a British prime minister to Germany for over 60 years. The last leader to visit the country was Benjamin Disraeli when he attended the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Members of the Czech government were horrified when they heard the news as they feared Chamberlain would accept Hitler's demands for the transfer of the Sudetenland to Germany. (14)

On 15th September, 1938, Chamberlain, aged sixty-nine, boarded a Lockheed Electra aircraft for a seven-hour journey to Munich, followed by a three-hour car ride up the long and winding roads to Berchtesgaden. The first meeting lasted for three hours. Hitler made it very clear that he intended to "stop the suffering" of the Sudeten Germans by force. Chamberlain asked Hitler what was required for a peaceful solution. Hitler demanded the transfer of all districts in Czechoslovakia with a 50 per cent or more German-speaking population. Chamberlain said he had nothing against the idea in principle, but would need to overcome "practical difficulties". (15)

Hitler flattered Chamberlain and this had the desired impact on him. He told his sister: "Horace Wilson heard from various people who were with Hitler after my interview that he had been very favourably impressed. I have had a conversation with a man, he said, and one with whom I can do business and he liked the rapidity with which I had grasped the essentials. In short I had established a certain confidence, which was my aim, and in spite of the hardness and ruthlessness I thought I saw in his face I got the impression that here was a man who could be relied upon when he had given his word." (16)

Chamberlain called an emergency cabinet meeting on 17th September. Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, recorded in his diary: "Looking back upon what he said, the curious thing seems to me now to have been that he recounted his experiences with some satisfaction. Although he said that at first sight Hitler struck him as 'the commonest little dog' he had ever seen, without one sign of distinction, nevertheless he was obviously pleased at the reports he had subsequently received of the good impression that he himself had made. He told us with obvious satisfaction how Hitler had said to someone that he had felt that he, Chamberlain, was 'a man.' But the bare facts of the interview were frightful. None of the elaborate schemes which had been so carefully worked out, and which the Prime Minister had intended to put forward, had ever been mentioned. He had felt that the atmosphere did not allow of them. After ranting and raving at him, Hitler had talked about self-determination and asked the Prime Minister whether he accepted the principle. The Prime Minister had replied that he must consult his colleagues. From beginning to end Hitler had not shown the slightest sign of yielding on a single point. The Prime Minister seemed to expect us all to accept that principle without further discussion because the time was getting on." (17)

Chamberlain told the cabinet that he was convinced "that Herr Hitler was telling the truth". Thomas Inskip, Minister for Coordination of Defence, and a loyal supporter of Chamberlain, felt uneasy by the prime minister's performance. He recorded in his diary: "The impression made by the P.M.'s story was a little painful. It was plain that Hitler had made all the running: he had in fact blackmailed the P.M." (18)

Oliver Stanley, President of the Board of Trade objected vigorously to Hitler's "ultimatum", and declared that "if the choice for the Government in the next four days is between surrender and fighting, we ought to fight". Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, Lord Privy Seal, said he was "prepared to face war in order to free the world from the continual threat of ultimatums". Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham, attempted to rally the cabinet to Chamberlain's cause with the defeatist statement that he thought that we "had no alternative but to submit to humiliation." (19)

It was Duff Cooper who was Chamberlain's harshest critic and wrote in his diary: "I argued that the main interest of this country had always been to prevent any one Power from obtaining undue predominance in Europe; but we were now faced with probably the most formidable Power that had ever dominated Europe, and resistance to that Power was quite obviously a British interest. If I thought surrender would bring lasting peace I should be in favour of surrender, but I did not believe there would ever be peace in Europe so long as Nazism ruled in Germany. The next act of aggression might be one that it would be far harder for us to resist. Supposing it was an attack on one of our Colonies. We shouldn't have a friend in Europe to assist us, nor even the sympathy of the United States which we had today. We certainly shouldn't catch up the Germans in rearmament. On the contrary, they would increase their lead. However, despite all the arguments in favour of taking a strong stand now, which would almost certainly lead to war, I was so impressed by the fearful responsibility of incurring a war that might possibly be avoided, that I thought it worth while to postpone it in the very faint hope that some internal event might bring about the fall of the Nazi regime. But there were limits to the humiliation I was prepared to accept." (20)

Chamberlain ignored his critics and without taking a vote he insisted the Cabinet had "accepted the principle of self-determination and given him the support he had asked for". Chamberlain claimed that his policy was very popular with the public and that he would love to show his colleagues "some of the many letters which he had received in the last few days, which showed the intense feeling of relief throughout the country, and of thankfulness and gratitude for the load which had been lifted, at least temporarily." (21) He told his sister, Ida Chamberlain, that he had "finally overcome all critics, some of whom had been concerting opposition beforehand." (22)

That evening Chamberlain and Halifax received a delegation at Downing Street from leaders of the Labour Party and the Trade Union movement. This included Hugh Dalton, Herbert Morrison and Walter Citrine. In the hour-and-a-half meeting, the men were highly critical of the government. Citrine pointed out that "British prestige had been gravely lowered by Chamberlain going to see Hitler. Dalton suggested that these were unlikely to be the last of Hitler's demands. "I believe that he intends to go on and on, until he dominates first all Central and South Eastern Europe, then all Europe, then the world." (23)

After the meeting Dalton wrote a scathing assessment of Chamberlain: "The best that can be said of the P.M. is that, within the limits of his ignorance, he is rational, but I am appalled how narrow these limits are, and it is clear that Hitler produced an enormous impression on him, partly by hustling intimidation and partly by a few compliments and words of courtesy. If Hitler had been a British nobleman and Chamberlain a British working man with an inferiority complex, the thing could not have been done better." (24)

On 18th September, 1938, Chamberlain and several of his ministers, met Edouard Daladier, the prime minister of France, in order to persuade him to agree to the orderly transfer of the Sudeten areas to Germany. Chamberlain said that unless we accept Hitler's demands, "we must expect that Herr Hitler's reply would be to give the order to march". According to Sir John Simon, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Daladier was overwhelmed by the emotional strain of attempting both to fulfil France's treaty obligations to Czechoslovakia, while at the same time avoiding war at any cost. (25)

Daladier admitted that the dilemma he faced was "to discover some means of preventing France from being forced into war as a result of her obligations and at the same time to preserve Czechoslovakia and save as much of that country as was humanly possible. Daladier told Chamberlain the French would agree to support Hitler's demands only in return for a British agreement to join the French alliance system in protecting other countries in eastern Europe, including guaranteeing what was left of Czechoslovakia. (26)

Chamberlain now had to sell the idea to the Cabinet. He faced a hostile reception to the idea and several members were very unhappy with the proposed guarantee to Czechoslovakia. What precise obligations did it entail? Was it to be a "joint" guarantee, to be implemented only when each and every guarantor wished to enforce it, or was it to be a "several" guarantee, meaning that in theory Britain could be called on to defend Czechoslovakia alone? Even the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, also found it difficult to defend. He conceded that he too "felt considerable misgivings about the guarantee, but... it would have been disastrous if there had been any delay in reaching agreement with the French". (27)

Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, was the most vociferous in voicing his concerns, principally on the strategic grounds that Czechoslovakia could not be defended. Once the Sudeten German areas had been transferred, it would become "an unstable State economically, would be strategically unsound, and there was no means by which we could implement the guarantee. It was difficult to see how it could survive." Hore-Belisha argued the proposals offered nothing more than "a postponement of the evil day." According to Thomas Inskip, Hore-Belisha got into an acrimonious discussion with a "tired and dispirited" Chamberlain. (28)

Samuel Hoare, the Home Secretary, was given the task of persuading the newspapers to support Chamberlain's plan. He began to hold daily meetings with proprietors and editors. One of the key figures he approached was Sir Walter Layton, the chairman of the News Chronicle. Layton agreed to help and when one of his young journalists returned from Prague with a secret document which revealed the detailed timetable for the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, he arranged for the story to be suppressed. Vernon Bartlett had his articles censored and when the newspaper editor, Gerald Barry, wrote an anti-Chamberlain leader, Layton sacked him. (29)

Sir Horace Wilson, a senior civil servant who worked closely with Chamberlain, was given the task of controlling the way appeasement was reported on the BBC. A subsequent internal BBC report on the meetings between Hitler and Chamberlain in 1938, revealed that "towards the end of August, when the international situation was daily growing more critical", Wilson made a number of veiled threats. The report also confirmed that "news bulletins as a whole inevitably fell into line with Government policy at this critical juncture." (30)

Paramount News released a newsreel featuring interviews with two senior British journalists who were critical of Chamberlain. British cinema audiences greeted "with considerable applause" the warning that "Germany is marching to a diplomatic triumph... Our people have not been told the truth." Conservative Central Office complained and Lord Halifax approached Joseph Kennedy, the American ambassador based in London, and asked for the offending interviews to be removed. Kennedy brought his influence to bear on Paramount's American holding company, and the offending newsreel was quickly withdrawn. (31)

On 19th September, 1938, Clement Attlee had a meeting with Neville Chamberlain about the negotiations with Hitler and demanded the recall of Parliament to discuss the crisis. Later that day the National Council of Labour issued a statement saying that it viewed "with dismay the reported proposals of the British and French Governments for the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia under the brutal threat of armed force by Nazi Germany and without prior consultation with the Czechoslovak Government. It declares that this is a shameful betrayal of a peaceful and democratic people and constitutes a dangerous precedent for the future." (32)

Some newspapers became hostile to the government's policy towards the Sudetenland. The Daily Herald commented angrily that the Czechs had been "betrayed and deserted by those who had given every assurance that there should be no dismembership of their country". (33) The News Chronicle reported that the "bewilderment is giving place to a feeling of indignation that Great Britain should be one of the instruments used to compel a small democratic country to agree to self-mutilation under the threat of force." (34) The Times, who had strongly supported appeasement, could not understand "how the Czechoslovak Government could" possibly accept the deal negotiated by Chamberlain. (35)

Conservative MPs also began to criticize the proposed deal. Anthony Eden told a constituency meeting that the "British people know that a stand must be made. They pray that it will not be made too late." (36) Leo Amery commented that the terms to which Chamberlain had signed up "amounted to nothing less than Czechoslovakia's destruction as an independent state." (37) Winston Churchill issued a statement that stated: "It is necessary that the nation should realise the magnitude of the disaster into which we are being led. The partition of Czechoslovakia under Anglo-French pressure amounts to a complete surrender by the Western Democracies to the Nazi threat of force." (38)

Chamberlain did receive support from the Duke of Windsor, the former King Edward VIII: "I would wish to express on behalf of the Duchess and myself, our very sincere admiration for the courageous manner in which you threw convention and precedent to the winds by seeking a personal meeting with Herr Hitler and flying to Germany. It was a bold step to take, but if I may so, one after my own heart, as I have always believed in personal contact as the best policy in a tight corner." (39)

Meanwhile the German government continuing to put pressure on Chamberlain to make a decision. Joseph Goebbels mounted a propaganda campaign against the Czech government. German newspapers claimed that women and children were mowed down by Czech armoured cars and that poison gas had been used against German-speaking demonstrators. (40) The Foreign Ministry ordered the Prague legation to instruct all "Reich-Germans in regions with Czechoslovak population, without attracting attention and only verbally, to send women and children out of the country." The following day instructions were given to military commanders concerning the invasion of Czechoslovakia. (41)

On the 19th September, 1938, President Eduard Beneš of Czechoslovakia had a meeting with his ministers and the leaders of the six coalition parties, and his military chiefs of staff. They discussed the issue for two days before issuing a statement rejecting the Anglo-French plan. Acceptance of the proposals would be unconstitutional, and would lead to the "complete mutilation of the Czechoslovak State in every respect". The statement also reminded the British and French about their own treaty obligations towards Czechoslovakia. (42)

British and French officials told President Beneš that if Czechoslovakia refused to accept the Anglo-French plan and war were to break out, then the Czech government would be held solely responsible and they would be given no military assistance. Beneš later recalled that the French official had "tears in his eyes" whereas the British official behaved coldly, shuffling uneasily and constantly looking down at the floor. "I had the impression that both of them were ashamed to the bottom of their hearts of the mission they had to discharge." (43)

President Beneš felt he had no option but to capitulate and announced that the country had been "disgracefully betrayed". He claimed that: "We had no other choice because we were left alone." One government minister stated that history would "pronounce its judgement on the events of these days. Let us have confidence in ourselves. Let us believe in the genius of our nation. We shall not surrender, we shall hold the land of our fathers." (44)

The following morning there was a general strike in Prague, and an even larger mass demonstration. Over 100,000 people demanded a military government, and a programme of national resistance. That evening the Czech government resigned. In its place President Beneš appointed a new, non-political Government of National Defence, to be headed by General Jan Syrový, the Inspector General of the army. Syrový issued a statement that night: "I guarantee that the Army stands and will stand on our frontiers to defend out liberty to the last. I may soon call upon you here to take an active part in the defence of our country in which we all going to join." (45)

Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister, told the assembly of the United Nations that the Soviet Union intended to fulfil its obligations towards Czechoslovakia, if France would do the same. (46) This created a serious problem for the Anglo-French plan and Chamberlain announced that he was going to have another meeting with Hitler. Chamberlain arrived in Godesberg on 22nd September. At their first meeting Hitler made a series of new demands. He now wanted the immediate occupation of Sudeten areas and non-German-speakers who wished to leave would be allowed to take only a single suitcase of belongings with them. He also added certain areas with less than 50 per cent German speakers and raised Polish and Hungarian grievances in other areas of Czechoslovakia. (47)

At another meeting the following day Chamberlain pleaded with him to return to the terms of the previous agreement. Chamberlain pointed out that he had already risked his entire political reputation to gain the Anglo-French plan and if he marched into the Sudetenland, his political career would be destroyed. He pointed out that when he left England he had been booed by the crowd at the airport. Hitler refused to budge and restated that he would occupy the Sudeten areas on 1st October. Chamberlain decided to break-off talks and return to London. (48)

Chamberlain had been right by the changing public mood in Britain. A Mass Observation poll found that 44 per cent of those questioned expressed themselves to be "indignant" at Chamberlain's policy, while only 18 per cent were supportive. Of those men who were questioned, 67 per cent said they were willing to fight to defend Czechoslovakia. On the day that he returned to London, a crowd of over 10,000 people massed in Whitehall, shouting "Stand by the Czechs!" and "Chamberlain must go!" (49)

Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, felt that it would be impossible for the Cabinet to support Chamberlain in his efforts to do a deal with Hitler. When he read Hitler's latest memorandum which laid out his demands he thought Chamberlain would advise the Cabinet to reject it. He was shocked when he discovered that Chamberlain wanted to accept these terms. "I was completely horrified. He was quite calmly for total surrender... Hitler has evidently hypnotised him to a point." (50)

On 24th September the Cabinet had a full-day meeting. Chamberlain told his ministers that he was "satisfied Herr Hitler would not go back on his word" and was not using the crisis as an excuse to "crush Czechoslovakia or dominate Europe." According to the Cabinet minutes: "In his view Herr Hitler had certain standards; he would not deliberately deceive a man whom he respected, and he was sure that Herr Hitler now felt some respect for him... He thought that he had now established an influence over Herr Hitler, and the latter trusted him. The Prime Minister believed that Herr Hitler was speaking the truth." (51)

Chamberlain had now lost the support of most of his Cabinet. Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, rejected Hitler's proposal, and called for the army to be mobilised. It was, he contended, "the only argument Hitler would understand". He then warned that the Cabinet "would never be forgiven if there were a sudden attack on us and we had failed to take the proper steps." Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, Walter Elliot, Oliver Stanley, Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton, all spoke against Hitler's proposals. (52)

Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, was the most critical of Hitler's proposals. He was always concerned that the government would achieve "peace with dishonour", now he feared "war with dishonour". Cooper pointed out the chiefs of staff had already called for mobilisation - "we might some day have to explain why we had disregarded their advice." Chamberlain responded angrily that the advice had only been given on the assumption that war was imminent. Cooper commented that it was "difficult to deny that any such danger existed". In his diary that night Cooper wrote: "Hitler has cast a spell over Neville". (53)

Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, the great supporter of appeasement, was now having doubts about the policy. He wrote to Chamberlain explaining: "It may help you if we give you some indication of what seems predominant public opinion as expressed in press and elsewhere. While mistrustful of our plan but prepared perhaps to accept it with reluctance as alternative to war, great mass of public opinion seems to be hardening in sense of feeling that we have gone to limit of concession and that it is up to Chancellor Hitler to make some contribution." (54)

Earl Winterton went to see Leo Amery, one of Chamberlain's oldest friends, and someone who was felt to have influence over the prime minister. He admitted that "at least four of five Cabinet members were seriously contemplating resignation." (55) Amery, who was against the deal wrote to Lord Halifax: "Almost everyone I have met, has been appalled by the so-called peace we have forced upon the Czechs." (56)

Amery also wrote a letter to Chamberlain, which he delivered himself. How, he asked, could Chamberlain expect the Czechs "to commit such an act of folly and cowardice?" If he failed to stand up to Hitler, he risked making Britain look "ridiculous as well as contemptible in the eyes of the world". Amery concluded the letter with the words: "If the country and the House should once suppose that you were prepared to acquiesce in or even endorse this latest demand, there would be a tremendous feeling of revulsion against you." (57)

Chamberlain's main concern was the changing views of Lord Halifax. At a Cabinet meeting on 25th September, he admitted he said that he no longer trusted Hitler: "He (Halifax) could not rid his mind of the fact that Herr Hitler had given us nothing and that he was dictating terms, just as though he had won a war but without having had to fight... he felt some uncertainty about the ultimate end which he wished to see accomplished, namely, the destruction of Nazism. So long as Nazism lasted, peace would be uncertain. For this reason he did not think it would be right to put pressure on Czechoslovakia to accept." (58)

Duff Cooper wrote in his diary that Halifax's comments "came as a great surprise to those who think as I do." (59) Leslie Hore-Belisha thanked Halifax for giving "a fine moral lead". Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham, previously a staunch ally of Chamberlain, produced a press cutting which listed in detail the many occasions on which Hitler had broken his word. Only two ministers supported Chamberlain, James Stanhope, the President of the Board of Education, and Kingsley Wood, the Secretary of State for Air, who argued that the prime minister's visits had "made a considerable impression in Germany and had probably done more to weaken Nazism than any other event in recent years." (60)

Neville Henderson, the British ambassador in Germany, pleaded with Chamberlain to go on negotiating with Hitler. He believed that the German claim to the Sudetenland in 1938 was a moral one, and he always reverted in his dispatches to his conviction that the Treaty of Versailles had been unfair to Germany. "At the same time, he was unsympathetic to feelers from the German opposition to Hitler seeking to enlist British support. Henderson thought, not unreasonably, that it was not the job of the British government to subvert the German government". (61)

Chamberlain also received support from Sir Eric Phipps, the British ambassador to France: "Unless German aggression were so brutal, bloody and prolonged as to infuriate French public opinion to the extent of making it lose its reason, war now would be most unpopular in France. I think therefore that His Majesty's Government should realise extreme danger of even appearing to encourage small, but noisy and corrupt, war group here. All that is best in France is against war, almost at any price." (62) Alexander Cadogan wrote a hostile reply demanding to know exactly what Phipps meant by "small, but noisy and corrupt, war group" and insisting that he should cast his net further a field in ascertaining the views of a more representative sample of French political opinion." (63)

On Sunday 25th September, Chamberlain had a meeting with Edouard Daladier, the prime minister of France. "He began with a lengthy exposition of the Godesberg discussions, liberally peppered with self-congratulatory remarks as to how he had stood up to Hitler. Daladier retorted that a meeting of his Council of Ministers that afternoon had unanimously rejected the Godesberg demands." (64) Daladier pointed out that it was now clear that Hitler's sole objective was "to destroy Czechoslovakia by force, enslaving her, and afterwards realising the domination of Europe". Chamberlain asked if this meant France would declare war on Germany? Daladier replied that "in the event of unprovoked aggression against Czechoslovakia, France would fulfil her obligations". (65)

The Czechoslovak government leaked details of the Godesberg demands to the British press. The Times included a statement from Leo Amery, attacking Chamberlain: "Are we to surrender to ruthless brutality a free people whose cause we have espoused but are now to throw to the wolves to save our own skins, or are we still able to stand up to a bully." (66) Chamberlain responded with the words: "How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing." (67)

Harold Macmillan, the Conservative MP, who had been a critic of the government's appeasement policy, later explained the mood of the British people at the time: "They were grimly, but quietly and soberly, making up their minds to face war. They had been told that the devastation of air attack would be beyond all imagination. They had been led to expect civilian casualties on a colossal scale. They knew, in their hearts, that our military preparations were feeble and inadequate. Yet they faced their ordeal with calm and dignity... We thought of air warfare in 1938, rather as people think of nuclear warfare today." (68)

Benito Mussolini suggested to Hitler that one way of solving this issue was to hold a four-power conference of Germany, Britain, France and Italy. This would exclude both Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, and therefore increasing the possibility of reaching an agreement and undermine the solidarity that was developing against Germany. On 28th September, 1938, Hitler announced he would settle the matter peacefully at a conference to be held at Munich, beginning the next day. (69)

Before they left for Munich, Chamberlain and Halifax met Tomas Masaryk, the Czechoslovak minister in London. Masaryk tried to insist that his country should be represented in these talks. However, he was told that Hitler had only agreed to the conference on condition that the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia were excluded. Masaryk replied: "If you have sacrificed my nation to preserve the peace of world, I will be the first to applaud you. But if not, gentlemen, God help your souls." (70)

The meeting ended with Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini signing the Munich Agreement which transferred the Sudetenland to Germany. "We, the German Führer and Chancellor and the British Prime Minister, have had a further meeting today and are agreed in recognizing that the question of Anglo-German relations is of the first importance for the two countries and for Europe. We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again. We are resolved that the method of consultation shall be the method adopted to deal with any other questions that may concern our two countries." (71)

Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) argued: "The Munich settlement, signed in the early hours of 30 September, resembled pre-1914 European diplomacy, with four major powers forcing a small nation, without the power to resist, to concede territory to a major power. The agreement deprived Czechoslovakia of its heavily fortified border defences, its rail communications were cut and a great deal of economic power was lost. The fate of the remainder of Czechoslovakia now lay at the discretion of the Nazi regime." (72)

Chamberlain and Daladier argued amongst themselves about who would tell the Czech government about the agreement. While they were doing this, the German Minister in Prague, beat them to it. He roused the Czech foreign minister, Kamil Krofta, from his bed at 5 a.m., and peremptorily presented him with a copy of the agreement just a few hours after it had been signed. The Czech government now realised that if they resisted Hitler's demands, they would have to fight the war on its own. At 12.30 p.m. Krofta made a statement: "The Government of the Czechoslovak Republic, in announcing his acceptance, declares also before the whole world its protest against the decisions which were taken unilaterally and without our participation." (73)

General Jan Syrový, announced the news at 5 p.m. "I am experiencing the gravest hour of my life. I would have been prepared to die rather than to go through this. We have had to choose between making a desperate and hopeless defence, which would have meant the sacrifice of an entire generation of our adult men, as well as of our women and children, and accepting, without a struggle and under pressure, terms which are without parallel in history for the ruthlessness. We were deserted. We stood alone." (74)

Neville Henderson defended the agreement signed at Munich and praised both Hitler and Chamberlain for reaching a compromise over Czechoslovakia: "Germany thus incorporated the Sudeten lands in the Reich without bloodshed and without firing a shot. But she had not got all that Hitler wanted and which she would have got if the arbitrament had been left to war... The humiliation of the Czechs was a tragedy, but it was solely thanks to Mr. Chamberlain's courage and pertinacity that a futile and senseless war was averted." (75)

Hitler agreed to sign what became known as the "Anglo-German declaration". It promised Britain and Germany would adopt "the method of consultation" in any future disputes and would "never go to war with one another again". Crowds cheered all along Chamberlain's route from the airport back to Buckingham Palace, where he was to brief King George VI on the incredible turn of events. He was greeted by more cheering crowds outside 10 Downing Street as he arrived home. A few minutes later, Chamberlain was persuaded to step forwards and make a speech from the first-floor window: "My good friends: this is the second time in our history that there has come back to Downing Street from Germany peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time." (76) Sir Orme Sargent, an Assistant Under-Secretary, said: "You might think that we'd won a major victory, instead of just betraying a minor country." (77)

Neville Chamberlain claimed that he received over 20,000 letters and telegrams of praise and numerous gifts from people at home and abroad. This included "countless fishing flies, salmon rods, Scottish tweed for suits, socks, innumerable umbrellas, pheasants and grouse, fine Rhine wines, lucky horseshoes, flowers from Hungary, 6000 assorted bulbs from grateful Dutch admirers and a cross from the Pope." When the Daily Sketch offered readers a free photograph of Chamberlain they received 90,000 applications. A group of French businessmen opened a fund to present him with a property in France, to reward him for persuading the French government to sign the Munich Agreement. A wealthy supporter of the Conservative Party donated £10,000 to Birmingham University to fund a scholarship in Chamberlain's name." (78).

A record was produced at the time entitled God Bless You Mr. Chamberlain which contained the line: "We're all mightily proud of you." This reflected the overwhelming sense of relief that war had been averted. The Times reflected the mood when it reported: "No conqueror returning from victory on the battlefield had come adorned with greater laurels." (79) The Daily Telegraph commented: "The news will be hailed with a profound and universal relief." (80)

The Daily Express reported: "Be glad in your hearts. Give thanks to your God. People of Britain, your children are safe. Your husbands and your sons will not march to war Peace is a victory for all mankind. If we must have a victor, let us choose Chamberlain. For the Prime Minister's conquests are mighty and enduring - millions of happy homes and hearts relieved of their burden. To him the laurels. And now let us go back to our own affairs. We have had enough of those menaces, conjured up from the Continent to confuse us." (81)

The main supporter of appeasement was the newspaper baron, Lord Rothermere, who held neo-fascist views. Adolf Hitler told George Ward Price, one of its journalists, "He (Lord Rothermere) is the only Englishman who sees clearly the magnitude of this Bolshevist danger. His paper is doing an immense amount of good." Hitler was kept informed about what British newspapers were saying about him. He was usually very pleased by what appeared in The Daily Mail. On 20th May 1937 he wrote to Lord Rothermere: "Your leading articles published within the last few weeks, which I read with great interest, contain everything that corresponds to my own thoughts as well." (82)

“Czechoslovakia is not of the remotest concern to us,” Lord Rothermere told the paper’s readers and after the meeting in Munich, the newspaper said the agreement they had struck with Germany “brings to Europe the blessed prospect of peace.” Robert Philpot has pointed out: "It is impossible to know whether Hitler regarded Rothermere as anything other than a useful idiot. Still, he did his best to appear sincere in his gratitude for the press magnate’s backing." (83) On the signing of the Munich Agreement, Lord Rothermere sent a telegram to Chamberlain: "My dear Fuhrer everyone in England is profoundly moved by the bloodless solution to the Czechoslovakian problem. People not so much concerned with territorial readjustment as with dread of another war with its accompanying bloodbath. Frederick the Great was a great popular figure. I salute your excellency's star which rises higher and higher." (84)

After the signing of the Munich Agreement, One of Hitler's senior aides, Captain Fritz Wiedemann, sent a letter to Lord Rothermere stating: "You know that the Führer greatly appreciates the work the princess did to straighten relations between our countries... it was her groundwork which made the Munich agreement possible." Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe, a Nazi agent and Lord Rothermere's mistress, wrote to Hitler at the same time congratulating him on his achievement: "There are moments in life that are so great - I mean, where one feels so deeply that it is almost impossible to find the right words to express one's feelings - Herr Reich Chancellor, please believe me that I have shared with you the experience and emotion of every phase of the events of the last weeks. What none of your subjects in their wildest dreams dared hope for - you have made come true. That must be the finest thing a head of state can give to himself and to his people. I congratulate you with all my heart." (85)

Conservative Central Office suggested that Chamberlain should take advantage of his popularity by calling a general election. Lord Halifax warned against this as he regarded Hitler as "a criminal lunatic" and considered it likely that he would break the Munich Agreement that would result in the government losing popularity. Halifax suggested the forming of a National government that should include Chamberlain's critics such as Anthony Eden and Clement Attlee. Chamberlain rejected the idea saying that this political problem "would be all over in three months". (86) Neville Henderson wrote to Chamberlain and told him to ignore these comments: "Millions of mothers will be blessing your name tonight for having saved their sons from the horrors of war. Oceans of ink will flow hereafter in criticism of your action." (87)

Lord Halifax had a far more realistic view of Hitler's view of the British government. Hitler saw Chamberlain as a very weak man and was convinced that he would never stand up to him. Hitler told his generals that :"Our enemies are small worms. I saw them at Munich." (88) After the last meeting with Chamberlain he said: "This has been my first international conference, and I can assure you that it will be my last. If ever that silly old man comes interfering here again with his umbrella, I'll kick him downstairs and jump on his stomach in front of photographers." (89)

However, some newspapers did object to the agreement. The Manchester Guardian reported: "Politically, Czechoslovakia is rendered helpless with all that it means to the balance of forces in Eastern Europe, and Hitler will be able to advance again, when it chooses, with greatly increased force." (90) The Daily Herald, a newspaper that supported the Labour Party, argued: "Czechoslovakia, having made so many sacrifices, has had to make another one under preemptory pressure from the British and French Governments. Thousands of people (not so much Czechs as anti-Nazi Sudeten Germans) are going to suffer. They must run for their lives or face the rubber truncheons and the concentration camps." (91)

Several ministers, including Duff Cooper, Oliver Stanley, Harry Crookshank and Leslie Hore-Belisha, were very unhappy with the Munich Agreement. Cooper explained how he felt as he arrived at 10 Downing Street following the signing of the agreement: "I was caught up in the large crowd that were demonstrating their enthusiasm and were cheering, laughing, and singing; and there is no greater feeling of loneliness than to be in a crowd of happy, cheerful people and to feel that there is no occasion for oneself for gaiety or for cheering. That there was every cause for relief I was deeply aware, as much as anybody in this country, but that there was great cause for self-congratulation I was uncertain." (92)

Chamberlain pleaded with the men to stay in the government in order to give an image of unity. However, on 3rd October, Cooper resigned. After a brief interview with Chamberlain, he made his way to Buckingham Palace to hand in his seals of office. King George VI was polite but frank: "He said he could not agree with me, but he respected those who had the courage of their convictions." (93) That evening the King issued a statement: "The time of anxiety is past. After the magnificent efforts of the Prime Minister in the cause of peace it is my fervent hope that a new era of friendship and prosperity may be dawning among the peoples of the world." (94)

The debate on the Munich Agreement in the House of Commons started on 3rd October, 1938. Cooper explained why he had resigned from the government and compared the situation with the outbreak of the First World War: "I thought then (1914), and I have always felt, that in any other international crisis that should occur our first duty was to make plain exactly where we stood and what we would do. I believe that the great defect in our foreign policy during recent months and recent weeks has been that we have failed to do so. During the last four weeks we have been drifting, day by day, nearer into war with Germany, and we have never said, until the last moment, and then in most uncertain terms, that we were prepared to fight. We knew that information to the opposite effect was being poured into the ears of the head of the German State. He had been assured, reassured, and fortified in the opinion that in no case would Great Britain fight."

Duff Cooper then went on to criticise Chamberlain: "The Prime Minister has believed in addressing Herr Hitler through the language of sweet reasonableness. I have believed that he was more open to the language of the mailed fist. I am glad so many people think that sweet reasonableness has prevailed, but what actually did it accomplish? The Prime Minister went to Berchtesgaden with many excellent and reasonable proposals and alternatives to put before the Fuhrer, prepared to argue and negotiate, as anybody would have gone to such a meeting. He was met by an ultimatum. So far as I am aware no suggestion of an alternative was ever put forward."

Cooper ended his speech with the words: "The Prime Minister may be right. I can assure you, Mr. Speaker, with the deepest sincerity, that I hope and pray that he is right, but I cannot believe what he believes. I wish I could. Therefore, I can be of no assistance to him in his Government. I should be only a hindrance, and it is much better that I should go. I remember when we were discussing the Godesberg ultimatum that I said that if I were a party to persuading, or even to suggesting to, the Czechoslovak Government that they should accept that ultimatum, I should never be able to hold up my head again. I have forfeited a great deal. I have given up an office that I loved, work in which I was deeply interested and a staff of which any man might be proud. I have given up associations in that work with my colleagues with whom I have maintained for many years the most harmonious relations, not only as colleagues but as friends. I have given up the privilege of serving as lieutenant to a leader whom I still regard with the deepest admiration and affection. I have ruined, perhaps, my political career. But that is a little matter; I have retained something which is to me of great value - I can still walk about the world with my head erect." (95)

In his reply to Cooper's resignation speech, Neville Chamberlain, defended his policy of appeasement. However, MPs interrupted his speech with cries of "Shame" when he pleaded for a greater understanding of Hitler's position. "I would like to say a few words in respect of the various other participants, besides ourselves, in the Munich Agreement. After everything that has been said about the German Chancellor today and in the past, I do feel that the House ought to recognise the difficulty for a man in that position to take back such emphatic declarations as he had already made amidst the enthusiastic cheers of his supporters, and to recognise that in consenting, even though it were only at the last moment, to discuss with the representatives of other Powers those things which he had declared he had already decided once for all, was a real and a substantial contribution on his part." (96)

Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, made the most significant attack on the Munich Agreement. "We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen today a gallant, civilized and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilization and humanity, receive a terrible defeat.... The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence." (97)

Winston Churchill now decided to break with the government over its appeasement policy and two days after Attlee's speech made his move. Churchill praised Chamberlain for his efforts: "If I do not begin this afternoon by paying the usual, and indeed almost invariable, tributes to the Prime Minister for his handling of this crisis, it is certainly not from any lack of personal regard. We have always, over a great many years, had very pleasant relations, and I have deeply understood from personal experiences of my own in a similar crisis the stress and strain he has had to bear; but I am sure it is much better to say exactly what we think about public affairs, and this is certainly not the time when it is worth anyone’s while to court political popularity."

Churchill went on to say the negotiations had been a failure: "No one has been a more resolute and uncompromising struggler for peace than the Prime Minister. Everyone knows that. Never has there been such instance and undaunted determination to maintain and secure peace. That is quite true. Nevertheless, I am not quite clear why there was so much danger of Great Britain or France being involved in a war with Germany at this juncture if, in fact, they were ready all along to sacrifice Czechoslovakia. The terms which the Prime Minister brought back with him could easily have been agreed, I believe, through the ordinary diplomatic channels at any time during the summer. And I will say this, that I believe the Czechs, left to themselves and told they were going to get no help from the Western Powers, would have been able to make better terms than they have got after all this tremendous perturbation; they could hardly have had worse."

It was now time to change course and form an alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. "After the seizure of Austria in March we faced this problem in our debates. I ventured to appeal to the Government to go a little further than the Prime Minister went, and to give a pledge that in conjunction with France and other Powers they would guarantee the security of Czechoslovakia while the Sudeten-Deutsch question was being examined either by a League of Nations Commission or some other impartial body, and I still believe that if that course had been followed events would not have fallen into this disastrous state. France and Great Britain together, especially if they had maintained a close contact with Russia, which certainly was not done, would have been able in those days in the summer, when they had the prestige, to influence many of the smaller states of Europe; and I believe they could have determined the attitude of Poland. Such a combination, prepared at a time when the German dictator was not deeply and irrevocably committed to his new adventure, would, I believe, have given strength to all those forces in Germany which resisted this departure, this new design." (98)

Despite this powerful speech Churchill did not vote against the Munich Agreement. Nor did the other Conservative MPs who had been critical of the government appeasement policy such as Duff Cooper, Anthony Eden, Leo Amery, Harold Macmillan, Harold Nicolson, Louis Spears, Robert Boothby, Brendan Bracken, Victor Cazalet, Sidney Herbert, Duncan Sandys, Leonard Ropner, Ronald Cartland, Ronald Tree, Paul Emrys-Evans, Vyvyan Adams and Jack Macnamara. The main reason why 20 Conservative MPs abstained rather than voting with the Labour Party was that Chamberlain threatened a general election if his motion was defeated. (99)

Robert Boothby, who only abstained at the time, later recalled: "The terms of the Munich Agreement turned out to be even worse than we had supposed. They amounted to unconditional surrender. Even Göring was shocked. He said afterwards that when he heard Hitler tell the conference at Munich (if such it could be called) that he proposed to occupy the Sudeten lands, including the Czech fortifications at once... But neither Chamberlain nor Daladier made a cheep of protest. Hitler did not even have to send an ultimatum to Czechoslovakia. Chamberlain did that for him." (100)

Lord Halifax believed Chamberlain had made a "bad speech" in the Munich Agreement debate and told him afterwards about his dissatisfaction. Chamberlain later commented: "I had a message from Halifax that he did not like the speech, as he thought it laid too much emphasis on appeasement and was not stiff enough to the dictators." Richard Austen Butler, the parliamentary under-secretary for foreign affairs, suggested that the problem was caused by Chamberlain not showing the speech to Halifax beforehand. (101)

The Myth of Appeasement and Rearmament

James P. Levy, in the book, Appeasement and Rearmament Britain (2006) argues that Neville Chamberlain crafted an active, logical and morally defensible foreign policy designed to avoid and deter a potentially devastating war and to give Britain the chance to rearm. However, because his strategy was unsuccessful, historians have been unkind to him: "Chamberlain became the collective whipping boy of a British establishment that was desperate to distance itself from what had been an overwhelmingly popular policy back in the 1930s but had failed to avert war and looked pathetic in retrospect." (102)

However, as Graham Macklin has pointed out in his book, Neville Chamberlain (2006): "Interpreting Chamberlain's motives at Munich are of pivotal importance in determining his legacy. Did he genuinely believe that Munich had pacified Europe or was he merely seeking to delay Hitler from being able to deal Britain, a terrible, perhaps mortal blow, and in doing so purchasing time for further rearmament? If it were the latter and indeed lobbying for rearmament to be accelerated." (103)

This was the same point made by Duff Cooper in his resignation speech. "The Prime Minister believes that he can rely upon the good faith of Hitler" but, he added, "how are we to justify the extra burden laid upon the people of Great Britain" in increasing or accelerating rearmament "if we are told at the same time that there is no fear of war with Germany and that, in the opinion of the Prime Minister, this settlement means peace in our time?" (104)

Herbrand Sackville, the President of the Board of Education, wrote to Chamberlain about the need to accelerate rearmament. He felt strongly "that we should immediately take new and drastic steps both to strengthen our defences and - almost equally important - to make it clear to the world that we are doing so." (105) Chamberlain replied: "I do not think we are very far apart, if at all, on what we should do now, but I do not want to pledge myself to any particular programme of armaments till we have had a chance to review the situation in the light of recent events." (106)

At a Cabinet meeting on 3rd October, 1938, Walter Elliot, Secretary of State for Scotland, argued that a "view... strongly held in certain quarters... that every effort should be made to intensify our rearmament programme". Lord Halifax, agreed and urged that ministers should not make speeches on rearmament "which would preclude consideration of the need for such intensification." (107) Chamberlain argued that if the government announced it planned to increase defence spending it would provide evidence that "Munich had made war more instead of less imminent." (108)

The Cabinet minutes records Chamberlain's attitude towards rearmament: "He (Chamberlain) had been oppressed with the sense that the burden of armaments might break our backs. This had been one of the factors which had led him to the view that it was necessary to try and resolve the causes which were responsible for the armament race. He thought that we were now in a more hopeful position, and that the contacts which had been established with the Dictator Powers opened up the possibility that we might be able to reach some agreement with them which would stop the armament race. It was clear, however, that it would be madness for the country to stop rearming until we were convinced that other countries would act in the same way... That, however, was not the same thing as to say that... we should at once embark on a great increase in our armaments programme." (109)

Anthony Eden, who had resigned as Foreign Secretary in protest against appeasement, was the strongest supporter in the Conservative Party for rearmament. In the House of Commons he called for "a national effort in the sphere of defence very much greater than anything that has been attempted hitherto... a call for a united effort by a united nation." (110) A week later Eden had a long talk with Lord Halifax, where he tried to persuade him to urge rapid rearmament. Halifax took this message to Chamberlain but it was rejected. (111)

Peter Neville, the author of Neville Chamberlain (1992), argues that Chamberlain's views on rearmament was influenced by his belief in social reform: "Chamberlain... worried about the cost of rearmament, and the way the arms race was affecting the programme of domestic reform in which he so much believed... If, Chamberlain reasoned, diplomacy could bring about an understanding profoundly worth striving for... His belief was that if the burden of arms spending became so heavy that it endangered Britain's economic recovery (still at a delicate stage after the Depression), then a diplomatic situation had to be found." (112)

Chamberlain's close friend, Sir George Joseph Ball, Director of the Conservative Research Department, played an important role in promoting the government's foreign policy. Ball controlled the anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi magazine, The Truth, that mounted a smear campaign against the critics of appeasement. Ball, a former member of MI5, arranged for the telephones of Churchill and Eden to be tapped. In the aftermath of Munich he dismantled the Foreign Office News Department, making 10 Downing Street the sole repository for government news. Another important figure was George Steward, Downing Street's chief press liaison officer who, MI5 discovered, had told an official at the German Embassy that Britain would "give Germany everything she asks for the next year". (113)

Ball urged Chamberlain to make use of his popularity by calling a snap election. His cabinet colleagues warned against this fearing that during the campaign Hitler would break the promises he made at Munich. Lord Halifax thought an election would be far too risky and urged Chamberlain to form a government of national unity. Halifax believed this government should include Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden and other critics of appeasement. (114)

Churchill wrote to Paul Reynaud, a French politician who was opposed to appeasement, claiming that it was the worst defeat for Britain since 1783. He claimed that the public mood was still pro-Munich for any campaign against Chamberlain's foreign policy to have an effect. Churchill even considered whether it might be best for Britain and France to do a deal with Hitler: "The question now presenting itself is: Can we make head against the Nazi domination, or ought we severally to make the best terms possible with it - while trying to rearm?" (115)

Chamberlain rejected the idea as the last thing he wanted to do was to reward those people who had made life difficult over the last few months. He pointed out that "our foreign policy was one of appeasement" with the central aim of "establishing relations with the Dictator Powers which will lead to a settlement in Europe and to a sense of stability". He said what he wanted, above all, was "more support for my policy, and not a strengthening of those who don't believe in it". (116)

Doubts about Appeasement

Gradually, the British public began to change their mind about what had agreed at Munich. By the end of October, 1938, virtually every Czech border fortification was in German hands, and any defence of those that remained was impossible. Its capital, Prague, was less than forty miles from the new frontier. Czechoslovakia had handed over to the Reich 11,000 square miles of territory that was inhabited by 2,800,000 Sudeten Germans and 800,000 Czechs. The country's communications infrastructure had been badly damaged and the country had lost three-quarters of its industrial production. (117)

On 27th October, 1938, a by-election took place as a result of the death of Robert Croft Bourne, the sitting Conservative Party MP. The local Labour and Liberal parties decided that they would support the anti-appeasement candidate, A. D. Lindsay, who was the was vice-chancellor of Oxford University. Lindsay, the former Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, was also involved in setting up several unemployment clubs in the town. During the campaign Lindsay argued: "Along with men and women of all parties I deplored the irresolution and tardiness of a Government which never made clear to Germany where this country was prepared to take a stand look with the deepest misgiving at the prospect before us ... all of us passionately desire a lasting peace, but we want a sense of security, a life worth living for ourselves and our children: not a breathing space to prepare for the next war." (118)

The Conservative candidate was Quintin Hogg, the son of Cabinet minister, Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham. Hogg argued that Lindsay was putting forward a negative message: "The issue in this election is going to be very clear. I am standing for a definite policy. Peace by negotiation. Mr. Lindsay is standing for no definite policy that he can name. He stands for national division against national unity. His policy is a policy of two left feet walking backward!"

Lindsay replied: "Suppose you had a child desperately ill. All night long you pray without ceasing, and in the morning she seems better. You thank God that your prayers have been answered. Then, later on it is discovered that owing to some error in the doctor's treatment, she is going to be disabled for the rest of her life. Would your gratitude to God for saving your daughter's life prevent you from calling in a better doctor who might restore your daughter to health? That is how I feel about our present very precarious peace. I am sure that Mr. Chamberlain did his best, but I know that it was also he who brought us very near to war. I am sure that it is owing to his policy that we are now in such a very dangerous situation. That is why I oppose him." (119)

Lindsay was defeated but reduced the Conservative majority from 6,645 to 3,434. However, soon afterwards another by-election was announced when Reginald Croom-Johnson, the sitting Conservative Party MP for Bridgwater, was appointed a High Court judge. Vernon Bartlett, a left-wing journalist, whose critical reports on Chamberlain's foreign policy had been censored by his newspaper, the News Chronicle, was persuaded to stand as an anti-appeasement candidate. The local Labour and Liberal parties decided not to put up a candidate and declared they would support Bartlett. (120)

On 18th November, 1938, Bartlett won the seat with 6,000 more votes than the combined Labour and Liberal votes at the previous election, turning an overall Conservative lead of 4,500 votes into a deficit of over 2,000. Henry Channon, the Tory MP, noted in his diary: "I am dumbfounded by the news of the Bridgewater election, where Vernon Bartlett, standing as an Independent, has had a great victory over the Government candidate. This is the worst blow the Government has had since 1935." (121)

In all the eight by-elections that followed the Munich Agreement, the Conservative Party suffered a fall in its support. Sir George Joseph Ball, Director of the Conservative Research Department, the man who had been trying to persuade Chamberlain to hold a snap General Election told him at the end of November, 1938: "The outlook is far less promising than it was a few months ago, and there are a large number of seats held by only small majorities, so that only a small turnover of votes would defeat the Government." Ball advised the election should be postponed. (122)

Winston Churchill was a strong supporter of the idea of a National Government and had a meeting with the Conservative Chief Whip, David Margesson, and told him of his "strong desire" to enter the Government and was willing to work closely with Chamberlain. An opinion poll in the News Chronicle showed fifty-six per cent wanted Churchill in the Government. However, his general popularity was still low. Anthony Eden, with thirty-eight per cent support, was the most popular choice to replace Chamberlain. Churchill was backed by only seven per cent of those interviewed. (123)

Clement Attlee had led the campaign against appeasement. This caused him problems in the Labour Party and there was a campaign to persuade Herbert Morrison to run against him for the leadership of the party. His critics thought he was being disloyal to work so closely with anti-appeasers such as Churchill and Eden. In November, 1938, Attlee made a speech where he rejected all talk of setting aside party differences because of the threat of war and pointed out that when this was done in 1931 it resulted in the "most incompetent Government in modern times." (124)

Stafford Cripps, on the left of the party, was also a critic of Attlee and in January, 1939, called for the creation of a Popular Front against fascism. This would be built of those across the political spectrum, including Churchill, who shared the desire to confront fascism and preserve democracy. Cripps also circulated it to the constituencies and as a result was expelled from the party. Nye Bevan was furious and argued: "If Sir Stafford Cripps is expelled for wanting to unite the forces of freedom and democracy, they can go on expelling others... His crime is my crime." (125)

Bevan supported Cripps and in an article in The Tribune, "Cripps was expelled because he claimed the right to tell the Party what he had already told the Executive... This is tantamount to a complete suppression of any opinion in the Party which does not agree with that held by the Executive... If every organised effort to change Party policy is to be described as an organised attack on the Party itself, then the rigidity imposed by Party discipline will soon change into rigor mortis." (126)

On 31st March 1939, Bevan, George Strauss and Charles Trevelyan were expelled from the Labour Party. Bevan continued to attack the NEC. So did other party members. David Low published a cartoon showing Colonel Blimp saying: "The Labour Party is quite right to expel all but sound Conservatives." However, they were readmitted in November 1939 after agreeing "to refrain from conducting or taking part in campaigns in opposition to the declared policy of the Party." (127)

Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Chamberlain believed that it was vitally important to persuade Benito Mussolini to advise Adolf Hitler not to embark on "some mad dog act". On 11th January, 1939, Chamberlain, accompanied by Halifax, arrived in Rome. Mussolini told Chamberlain that Italy desired peace but gave no promise to restrain Hitler. Count Galeazzo Ciano, the Italian foreign minister, wrote in his diary that it was clear that the British are unwilling to fight in any future war. In private, Mussolini said of his British visitors: "These men are not made of the same stuff as Francis Drake and the other magnificent adventurers who created the Empire." (128) Chamberlain took a very different view of the meeting describing the visit as "truly wonderful" because it had "strengthened the channels of peace". (129)

On 15th March 1939, Nazi tanks entered Prague and destroyed the Munich agreement. The annexation of an area peopled by non-Germans showed that Hitler was going further than redressing the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles. At a Cabinet meeting it was agreed that the government would find a form of words in order to back out of honouring what amounted to a moral guarantee to Czechoslovakia implicit in the Munich agreement, but never formally ratified in the months which followed by Britain, France, Germany and Italy. Chamberlain refused to accept that his appeasement policy had failed: "Though we may have to suffer checks and disappointments, from time to time, the object that we have in mind is of too great significance to the happiness of mankind for us lightly to give it up." (130)

The Manchester Guardian reported: "Prague, a sorrowing Prague, yesterday had its first day of German rule - a day in which the Czechs learned of the details of their subjection to Germany, and in which the Germans began their measures against the Jews... Bridges were occupied by troops and each bridge-head had a heavy machine-gun mounted on a tripod and pointing to the sky. Every twenty yards along the pavement two machine-guns were mounted facing each other. Suicides have begun. The fears of the Jews grow. The funds of the Jewish community have been seized, stopping Jewish relief work. The organization for Jewish emigration has been closed." (131)

Nevile Henderson was devastated by Hitler's action: "Hitler had staged another of his lightning coups, and once more the world was left breathless... By the occupation of Prague, Hitler put himself once for all morally and unquestionably in the wrong, and destroyed the entire arguable validity of the German case as regards the Treaty of Versailles... By his callous destruction of the hard and newly won liberty of a free and independent people, Hitler deliberately violated the Munich Agreement, which he had signed not quite six months before, and his undertaking to Mr. Chamberlain, once the Sudetenlands had been incorporated in the Reich, to respect the independence and integrity of the Czech people." (132)

David Low, one of his main critics wrote: "He wanted peace - but so did we all. No one impugned his motives, but only his judgment. That his appeasement approach to Hitler was wrong was soon demonstrated, for the ink was hardly dry on the Munich agreement before the Führer was openly and noisily preparing his next step. But devotion to Chamberlain was so strong that his friends were unwilling to admit it. Having committed themselves to a fairy-tale, they could not bring themselves to face cold reality." (133)

Newspapers that had been very supportive of Chamberlain's appeasement policy were now highly critical of the way the government was dealing with Nazi Germany. For example, The Times, the most consistent supporter of appeasement among in the national press, suggested that "German policy no longer seeks the protection of a moral case" and urged a policy of close co-operation with other nations to resist Hitler. (134) Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail, did not have these concerns. In a letter intercepted by the British intelligence services Rothermere congratulated Hitler "on his walk into Prague" and urged him to invade Romania. (135)

Primary Sources

(1) Neville Chamberlain, letter to King George VI (13th September, 1938)

The continued state of tension in Europe which has caused such grave concern throughout the world has in no way been relieved, and in some ways been aggravated by the speech delivered at Nuremberg last night by Herr Hitler. Your Majesty's Ministers are examining the position in the light of his speech, and with the firm desire to ensure, if this is at all possible, that peace may be restored.

On the one hand, reports are daily received in great numbers, not only from official sources but from all manner of individuals who claim to have special and unchangeable sources of information. Many of these (and of such authority as to make it impossible to dismiss them as unworthy of attention) declare positively that Herr Hitler has made up his mind to attack Czechoslovakia and then to proceed further East. He is convinced that the operation can be effected so rapidly that it will be all over before France or Great Britain could move.

On the other hand, Your Majesty's representative in Berlin has steadily maintained that Herr Hitler has not yet made up his mind to violence. He means to have a solution soon - this month - and if that solution, which must be satisfactory to himself, can be obtained peacefully, well and good. If not, he is ready to march.

In these circumstances I have been considering the possibility of a sudden and dramatic step which might change the whole situation. The plan is that I should inform Herr Hitler that I propose at once to go over to Germany to see him. If he assents, and it would be difficult for him to refuse, I should hope to persuade him that he had an unequalled opportunity of raising his own prestige and fulfilling what he has so often declared to be his aim, namely the establishment of an Anglo-German understanding, preceded by a settlement of the Czechoslovakian question.

Of course I should not be able to guarantee that Dr. Benes would accept this solution, but I should undertake to put all possible pressure on him to do so. The Government of France have already said that they would accept any plan approved by Your Majesty's Government or by Lord Runciman.

(2) Hannah Senesh, diary entry (17th September, 1938)

We're living through indescribably tense days. The question is: Will there be war? The mobilization going on in various countries doesn't fill one with a great deal of confidence. No recent news concerning the discussions of Hitler and Chamberlain. The entire world is united in fearful suspense, for one, feel a numbing indifference because of all this waiting. The situation changes from minute to minute. Even the idea there may be war is abominable enough.

(3) Neville Chamberlain held a Cabinet meeting on 24th September 1938. Duff Cooper , First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote about it in his autobiography, Old Men Forget (1953)

The Cabinet met that evening. The Prime Minister looked none the worse for his experiences. He spoke for over an hour. He told us that Hitler had adopted a certain position from the start and had refused to budge an inch from it. Many of the most important points seemed hardly to have arisen during their discussion, notably the international guarantee. Having said that he had informed Hitler that he was creating an impossible situation, having admitted that he had "snorted" with indignation when he read the German terms, the Prime Minister concluded, to my astonishment, by saying that he considered that we should accept those terms and that we should advise the Czechs to do so.