Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan, the grandson of Daniel Macmillan (1813-1857), the publisher, was born in 1894. In his memoirs he described his mother as having "high standards and demanding high performances". He added: "I can truthfully say that I owe everything all through my life to my mother's devotion and support".

Macmillan attended Summer Fields School in Oxford. He later admitted that his shyness caused him problems at school and that he returned home with a "perpetual terror of becoming in any way conspicuous". He also suffered from periods of depression: "I was oppressed by some kind of mysterious power which would be sure to get me in the end. One felt that something unpleasant was more likely to happen than anything pleasant."

In 1906 Macmillan won a scholarship to Eton. However, over the next three years he suffered poor health. His biographer, Alistair Horne, wrote in Macmillan: The Making of a Prime Minister (1988): "Harold never finished Eton. He seems to have suffered from poor health and in his first half contracted pneumonia, from which he only just survived. Three years later some form of heart trouble was evidently diagnosed, and in 1909 he returned home as a semi-invalid."

Macmillan won a place at Balliol College in 1912. His personal tutor was Ronald Knox, who became an important influence on his intellectual development. Macmillan later recalled: "He influenced me because he was a saint... the only man I have ever known who really was a saint." Soon afterwards Knox became an Anglican Chaplain.

While at university Macmillan became involved in politics. He joined the Canning Club (Conservative), the Russell Club (Liberal) and the Fabian Society (Socialist). At meetings of the Oxford Union he supported progressive causes such as women's suffrage. He also voted for the motion: "That this House approves the main principles of socialism." Macmillan supported the "radical wing" of the Liberal Party during this period and was greatly impressed with David Lloyd George, who made an entertaining speech at the university in 1913.

He was elected Secretary of the Oxford Union in November 1913 and was fully expected to eventually become President of the Union if it had not been for the outbreak of the First World War. At the time Macmillan was suffering from appendicitis but as soon as he recovered he joined the Grenadier Guards. He was commissioned and as a second lieutenant he was sent to a training battalion at Southend-on-Sea.

Macmillan left for France on 15th August, 1915. When they arrived on the Western Front one of Macmillan's tasks was to read and censor the letters that his men sent home to their loved ones. He wrote to his mother about this task: "They have big hearts, these soldiers, and it is a very pathetic task to have to read all their letters home. Some of the older men, with wives and families who write every day, have in their style a wonderful simplicity which is almost great literature.... And then there comes occasionally a grim sentence or two, which reveals in a flash a sordid family drama."

On 27th September 1915, Macmillan took part in the offensive at Loos. Macmillan remembered being addressed by the Corps Commander, who assured them, "Behind you, gentlemen, in your companies and battalions, will be your Brigadier; behind him your Divisional Commander, and behind you all - I shall be there." At that point Macmillan heard a fellow officer comment in a loud stage whisper, "Yes, and a long way behind too!".

Macmillan was shot through his right hand towards the end of the battle. He was evacuated to hospital and although it was not a serious wound he never recovered the strength of that hand, which affected the standard of his handwriting. It also was responsible for what became known as "limp handshake". The British Army lost nearly 60,000 men at Loos for the advance of just a couple of miles.

After receiving treatment in London Macmillan was sent back to the Western Front in April 1916. The following month he gave an insight into life in the trenches. "Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about a modern battlefield is the desolation and emptiness of it all.... One cannot emphasise this point too much. Nothing is to be seen of war or soldiers -only the split and shattered trees and the burst of an occasional shell reveal anything of the truth. One can look for miles and see no human being. But in those miles of country lurk (like moles or rats, it seems) thousands, even hundreds of thousands of men, planning against each other perpetually some new device of death. Never showing themselves, they launch at each other bullet, bomb, aerial torpedo, and shell."

Macmillan took part in the offensive at the Somme. In July 1916, Macmillan was wounded while leading a patrol in No Man's Land: "They challenged us, but we could not see them to shoot, and of course they were entrenched while we were in the open. So I motioned to my men to lie quite still in the long grass. Then they, began throwing bombs at us at random. The first, unluckily, hit l me in the face and back and stunned me for the moment."

Macmillan was only in hospital for a couple of days and by the end of the month he moved with his battalion to Beaumont-Hamel. He wrote to his mother that the area was beautiful and that it was "not the weather for killing people." In another letter he said "the flies are again a terrible plague, and the stench from the dead bodies which lie in heaps around is awful."

On 15th September 1916 Macmillan was wounded again during an attack on the German trenches. Shot in the leg he took refuge in a shell-hole where he "pretended to be dead when any Germans came near." He took morphine which sent him into a deep sleep until he was found by members of the Sherwood Foresters.

Once again he described to his mother what happened during the attack: "The German artillery barrage was very heavy, but we got through I the worst of it after the first half-hour. I was wounded slightly in the right knee. I bound up the wound at the first halt, and was able to go on... About 8.20 we halted again. We found that we were being held up on the left by Germans in about 500 yards of uncleared trench. We attempted to bomb and rush down the trench. I was taking a party across to the left with a Lewis gun, to try and get in to the trench, when I was wounded by a bullet in the left thigh (apparently at close range). It was a severe wound, and I was quite helpless. I dropped into a shell-hole, shouted to Sgt. Robinson to take command of my party and go on with the attack."

Macmillan had received serious wounds and the surgeons decided it would be too risky to attempt to remove the bullet fragments from his pelvis. As Alistair Horne pointed out: "Because of the length of time it had taken to get him to proper medical care, combined with the primitiveness and lack of modern drugs in First World War hospitals, the wound closed up before being drained of all infection. Abscesses formed inside, poisoning his whole system."

Macmillan was returned to England and for a while his life seemed to be in danger. His mother arranged for him to be transferred to a private hospital in Belgrave Square. Later Macmillan claimed that "my life was saved by my mother's action. The pain was so bad that over the next two years he had to submit to anesthetic each time his dressings were changed.

After the Armistice, Macmillan joined the family publishing company. He took a keen interest in politics and for a while he was tempted to join the Liberal Party. However, he calculated that the party was in decline and decided instead to join the Conservative Party. In the 1924 General Election he became the Conservative MP for Stockton-on-Tees. Defeated in the 1929 General Election he returned in to the House of Commons in 1931.

Macmillan was a strong believer in social reform and his left-wing views were unpopular with the Conservative Party leadership. Macmillan was also highly critical of the foreign policies of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain and remained a backbencher until in 1940 Winston Churchill invited him to join the government as parliamentary secretary to the ministry of supply. In 1942 Macmillan was sent to North Africa where he filled the new cabinet post as minister at Allied Headquarters.

Harold Macmillan was defeated in the 1945 General Election. He wrote about the new Labour government: "I hate uneducated people having power; but I like to think that the poor will be rendered happy." He returned to the House of Commons later that year in a by-election at Bromley.

The Labour Party MP, Emrys Hughes, claimed that: "Macmillan had an oratorical style of the Gladstonian period. He would put his hands on the lapels of his coat and turn to the back benches behind him for approval and support. He would raise and lower his voice and speak as if he were on the stage... His polished phrases reeked of midnight oil... Did he know when he was acting and when he was not himself?" Michael Foot agreed and admitted that he "could hardly bear to listen to - Macmillan speak as he was so affected, pompous and portentous."

Bruce Lockhart had a much higher opinion of Macmillan and predicted that he would succeed Winston Churchill as leader of the Conservative Party: "He has grown in stature during the war more than anyone.... He was always clever, but was shy and diffident, had a clammy handshake and was more like a wet fish than a man. Now he is full of confidence and is not only not afraid to speak but jumps in and speaks brilliantly."

Macmillan eventually developed a good opinion of Clement Attlee. He wrote that: "If Attlee lacked charm, he did not lack courage. If he drifted into difficulties, he generally found a way out of them." He also admitted that on matters such as the nationalisation of public utilities "our views are not very far apart." Macmillan also admired Aneurin Bevan: "He was a genuine man. There was nothing fake or false about him. If he felt a thing deeply, he said so and in no uncertain terms... he expressed... the deepest feelings of humble people throughout the land."

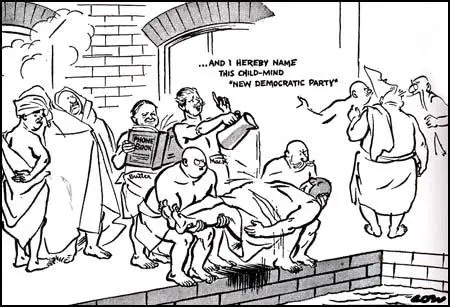

In 1946 Winston Churchill asked Macmillan to join a committee to look into reshaping the Conservative Party. On 3rd October, Macmillan published an article in the Daily Telegraph where he suggested that the name should be changed to the "New Democratic Party". In the article he called for the Liberal Party to join Conservatives in an anti-socialist alliance. He wrote in his diary that to obtain an alliance with the Liberals, it would be worthwhile "to offer proportional representation in the big cities in exchange."

After the 1951 General Election, Winston Churchill appointed Macmillan as his Minister of Housing. Macmillan was seen as one of the major successes in Churchill's government and received praise for achieving his promised target of 300,000 new houses a year. This was followed by a series of senior posts in the government: Minister of Defence (October, 1954 to April, 1955), Foreign Secretary (April, 1955 to December, 1955) and Chancellor of the Exchequer (December, 1955 to January 1957).

Anthony Eden replaced Winston Churchill as prime minister in April, 1955. The following year Gamal Abdel Nasser announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam. Eden feared that Nasser intended to form an Arab Alliance that would cut off oil supplies to Europe. Secret negotiations took place between Britain, France and Israel and it was agreed to make a joint attack on Egypt.

On 29th October 1956, the Israeli Army invaded Egypt. Two days later British and French bombed Egyptian airfields. British and French troops landed at Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal on 5th November. By this time the Israelis had captured the Sinai peninsula. President Dwight Eisenhower and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, grew increasingly concerned about these developments and at the United Nations the representatives from the United States and the Soviet Union demanded a cease-fire. When it was clear the rest of the world were opposed to the attack on Egypt, and on the 7th November the governments of Britain, France and Israel agreed to withdraw. They were then replaced by UN troops who policed the Egyptian frontier.

Gamal Abdel Nasser now blocked the Suez Canal. He also used his new status to urge Arab nations to reduce oil exports to Western Europe. As a result petrol rationing had to be introduced in several countries in Europe. In failing health, Anthony Eden resigned on 9th January, 1957.

Macmillan now became Britain's new prime minister. Macmillan was accused of cronyism when he appointed seven former Etonians to his Cabinet. Macmillan concentrated his attentions on the economy.

Macmillan attempted to heal the relationship with the United States after the Suez Crisis. He enjoyed a good relationship with President Dwight Eisenhower and the two men had a successful conference in Bermuda in March 1957.

Macmillan was the first Conservative prime minister to accept that countries within the British Empire should be given their freedom. In 1957, the Gold Coast, Ghana, Malaya and North Borneo were granted their independence.

In January 1958, Macmillan refused to introduce strict controls on money and the three Treasury ministers Peter Thorneycroft, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Birch, Economic Secretary to the Treasury, and Enoch Powell, the Financial Secretary to the Treasury, resigned.

Macmillan's economic policies resulted in an economic boom and a reduction in unemployment and he easily won the 1959 General Election by increasing his party's majority from 67 to 107 seats. It has been claimed that the main reason for this success was a growth in working-class income. Richard Lamb argued in The Macmillan Years 1957-1963 (1995) that "The key factor in the Conservative victory was that average real pay for industrial workers had risen since Churchill’s 1951 victory by over 20 per cent".

In February 1959 Macmillan became the first British prime minister to visit the Soviet Union since the Second World War. Talks with Nikita Khrushchev eased tensions in East-West relations over West Berlin and led to an agreement in principle to stop nuclear tests.

Macmillan's tradition as a social reformer was reflected in his "wind of change" speech at Cape Town in 1960 where he acknowledged that countries within the British Empire would be given their independence. Nigeria, the Southern Cameroons and British Somaliland were granted independence in 1960, Sierra Leone in 1961, Uganda in 1962, and Kenya and Tanzania in 1963.

The introduction of the system of life peerages to the House of Lords and the creation of the National Economic Development Council were other examples of unlikely Conservative measures and showed that Macmillan retained his liberal instincts.

In October, 1963, ill-health forced Macmillan to resign from office. After his retirement, Macmillan wrote Winds of Change (1966), The Blast of War (1967), Tides of Fortune (1969), Riding the Storm (1971) and At the End of the Day (1972).

Granted the title Earl of Stockton, Harold Macmillan died in 1986.

YouTube

Primary Sources

(1) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (30th August, 1915)

They have big hearts, these soldiers, and it is a very pathetic task to have to read all their letters home. Some of the older men, with wives and families who write every day, have in their style a wonderful simplicity which is almost great literature.... And then there comes occasionally a grim sentence or two, which reveals in a flash a sordid family drama.

(2) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (26th September, 1915)

A stream of motor-ambulances kept passing us, back from the firing line. Some of the wounded were very cheerful. One fellow I saw sitting up, nursing gleefully a German officer's helmet. "They're running!" he shouted. The wildest rumours were afloat.... But our men were much encouraged, and we stood on that road from 3.30-9.30 and sang almost ceaselessly, "Rag-time" - and music-hall ditties, sentimental love-songs - anything and everything. It was really rather wonderful.

(3) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (13th May, 1916)

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about a modern battlefield is the desolation and emptiness of it all.... One cannot emphasise this point too much. Nothing is to be seen of war or soldiers -only the split and shattered trees and the burst of an occasional shell reveal anything of the truth. One can look for miles and see no human being. But in those miles of country lurk (like moles or rats, it seems) thousands, even hundreds of thousands of men, planning against each other perpetually some new device of death. Never showing themselves, they launch at each other bullet, bomb, aerial torpedo, and shell. And somewhere too (on the German side we know of their existence opposite us) are the little cylinders of gas, waiting only for the moment to spit forth their nauseous and destroying fumes. And yet the landscape shows nothing of all this - nothing but a few shattered trees and 3 or 4 thin lines of earth and sandbags; these and the ruins of towns and villages are the only signs of war anywhere visible. The glamour of red coats - the martial tunes of fife and drum - aides-de-camp scurrying hither and thither on splendid chargers - lances glittering and swords flashing - how different the old wars must have been. The thrill of battle comes now only once or twice in a twelvemonth. We need not so much the gallantry of our fathers; we need (and in our army at any rate I think you will find it) that indomitable and patient determination which has saved England over and over again. If any one at home thinks or talks of peace, you can truthfully say that the army is weary enough of war but prepared to fight for another 50 years if necessary, until the final object is attained.

I don't know why I write such solemn stuff. But the daily newspapers are so full of nonsense about our "exhaustion" and people at home seem to be so bent on petty personal quarrels, that the great issues (one feels) are becoming obscured and forgotten. Many of us could never stand the strain and endure the horrors which we see every day, if we did not feel that this was more than a War - a Crusade. I never see a man killed but think of him as a martyr. All the men (though they could not express it in words) have the same conviction - that our cause is right and certain in the end to triumph. And because of this unexpressed and almost unconscious faith, our allied armies have a superiority in morale which will be (some day) the deciding factor.

(4) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (10th July, 1916)

A dug-out in the trenches is a very different affair - It's like nothing but a coffin, is damp, musty, unsafe, cramped - 5ft; long - 4ft broad - 3ft high. It can only be entered by a gymnastic feat of some skill. To get out of it is well-nigh impossible. ... It; is an evil thing, a poor thing, but (unluckily) mine own and (for the shelter and comfort that with all its failings it contrives to; afford me) I love it!

(5) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (20th July, 1916)

They challenged us, but we could not see them to shoot, and of course they were entrenched while we were in the open. So I motioned to my men to lie quite still in the long grass. Then they, began throwing bombs at us at random. The first, unluckily, hit l me in the face and back and stunned me for the moment.... A lot of flares were fired, and when each flare went up, we flopped down in the grass and waited till it had died down.... it was not till I got back in the trench that I found I was also hit just above the left temple, close to the eye. The pair of spectacles which I was wearing must have been blown off by the force of the explosion, for I never saw them again. Very luckily they were not smashed and driven into my eye.... I thought of you all at home in the second that the bomb exploded in my face. The Doctor told me that I asked for my Mother when I woke up this morning. And now I think of you all, dear ones at home, and feel so grateful that God has protected me once more.

(6) Harold Macmillan, letter to his mother, Helen Macmillan (15th September, 1916)

The German artillery barrage was very heavy, but we got through I the worst of it after the first half-hour. I was wounded slightly in the right knee. I bound up the wound at the first halt, and was able to go on.... About 8.20 we halted again. We found that we were being held up on the left by Germans in about 500 yards of uncleared trench. We attempted to bomb and rush down the trench. I was taking a party across to the left with a Lewis gun, to try and get in to the trench, when I was wounded by a bullet in the left thigh (apparently at close range). It was a severe wound, and I was quite helpless. I dropped into a shell-hole, shouted to Sgt. Robinson to take command of my party and go on with the attack. Sgt. Sambil helped me tie up the wound. I had no water, as the bullet had previously gone through my water bottle.

(7) Harold Macmillan, interviewed by Alistair Horne about being badly wounded on 15th September, 1916 (1979)

Bravery is not really vanity, but a kind of concealed pride, because everybody is watching you. Then I was safe, but alone, and absolutely terrified because there was no need to show off any more, no need to pretend ... there was nobody for whom you were responsible, not even the stretcher bearers. Then I was very frightened.... I do remember the sudden feeling - you went through a whole battle for two days ... suddenly there was nobody there ... you could cry if you wanted to.

(8) Emrys Hughes, Macmillan: Portrait of a Politician (1962)

Macmillan had an oratorical style of the Gladstonian period. He would put his hands on the lapels of his coat and turn to the back benches behind him for approval and support. He would raise and lower his voice and speak as if he were on the stage... His polished phrases reeked of midnight oil... Did he know when he was acting and when he was not himself?

(9) Rab Butler, The Art of the Possible (1971)

Macmillan was reared in a very tough school in politics. Permanently influenced by the unemployment and suffering in his constituency in the. North-East.... the fact that he had spent much of his early life as a rebel while I was a member of the despised and declining "establishment" underlines a difference of temperament between us. It may also lie at the root of our future relationship. But in political philosophy we were not far apart.

(10) Alistair Horne, Macmillan: The Making of a Prime Minister (1988)

Following the Party conference at Blackpool in October 1946, a committee was set up under Butler to produce a document restating Conservative policy. From the Opposition front benches, Macmillan was one of those most closely involved. Already by the summer of 1946, he had put in some serious political thought on reshaping the Party. In one of the more profound philosophic passages of his memoirs, he argues how Peel had been "the first of modern Conservatives", insofar as he understood that after a major debacle a party could only be rebuilt by means of "a new image". Peel had achieved this in part by changing the name of the party from Tory to Conservative, and Macmillan began to float ideas about a "New Democratic Party".

(11) Brendan Bracken, reported to Lord Beaverbrook on the 1946 Conservative Conference (1946)

The neo-Socialists, like Harold Macmillan, who are in favour of nationalising railways, electricity, gas and many other things, expected to get great support from the delegates.... It turned out that the neo-Socialists were lucky to escape with their scalps. The delegates would have nothing to do with the proposal to change the party's name. They demanded a real Conservative policy instead of a synthetic Socialist one so dear to the heart of the Macmillans and the Butlers, and it gave Churchill one of the greatest receptions of his life.

(12) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986)

I already had a perfectly genial relationship with Harold Macmillan, a clubbable person by nature, and we often used to find ourselves in conversation in the Smoking Room. For the first nine months of the Eden Government he had been Foreign Secretary. 'After a few months learning geography,' he complained to me, 'now I've got to learn arithmetic.' He was a consummate parliamentarian and quickly mastered his brief, as he had in every previous senior office he had held. There must have been a chemistry at work which brought out the best in both of us, and the debates on his first budget and Finance Bill became popular occasions. I suddenly developed an aptitude for dealing with serious economic and financial problems in a humorous and personal way, to which Macmillan responded.

He and I had a happy and stimulating relationship. In those days, even on the committee stage of the Finance Bill, the House would fill up to listen to the most abstruse amendments and hear us knocking each other about. After a gladiatorial exchange, the Chancellor would pass me a note, usually suggesting a drink in the Smoking Room, occasionally congratulating me on my attack on him, sometimes asking a question about how I had prepared my speech.

(13) Harold Wilson, speech in the House of Commons on Harold Macmillan (February, 1962)

In their rush to get into Europe they must not forget the four-fifths of the world's population whose preoccupation is with emergence from colonial status into self-government; and into the revolution of rising expectations. If this is so, is the world organization not to reflect the enthusiasms and aspirations of the new members and new nations entering into their inheritance, often through British action, as the Prime Minister said, and who want to see their neighbours also brought forward into the light? It must be recognized that this is the greatest force in the world today, and we must ask why it is so often that we are found, or thought to be found, on the wrong side.

The record of this country since the war, under both Governments, is good enough to proclaim to the world - India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon, Ghana, Nigeria, Tanganyika and Sierra Leone and, even after the agonies, Cyprus. Why do we contrive it that in the eyes of the world we are so often allied with reactionary governments, whose record in the scales of human enfranchisement weigh as a speck of dust against real gold and silver as far as our record is concerned?

Why is it that the British Foreign Secretary speaks in accents of the dead past, as though he fears and resents the consequences of the very actions which his Government as well as ours have taken?

Not only in this country but abroad people are asking, 'Who is in charge? Whose hand is on the helm? When is the Prime Minister going to exert himself and govern?' I do not believe that he can. The panache has gone. On every issue, domestic and foreign, now we find the same faltering hand, the same dithering indecision and confusion. What is more, Hon. Members opposite know it, and some of them are even beginning to say it.

The MacWonder of 1959 is the man who gave us this pathetic performance this afternoon. This whole episode has justified our insistence eighteen months ago that the Foreign Secretary should have been in the House of Commons. But we were wrong on one thing. We thought that the noble lord would be an office boy. The Prime Minister was able to restore his tottering position today only by a fulsome tribute to the noble lord. Indeed, to adopt the saying made famous by Nye Bevan: 'It is a little difficult to know which is the organ grinder and which is the other.'

(14) Edward Heath, The Course of My Life (1988)

Eden's successor, Harold Macmillan, had by far the most constructive mind I have encountered in a lifetime of politics. He took a fully informed view of both domestic and world affairs, and would put the tiniest local problem into a national context, and any national problem into its rightful position in his world strategy. Macmillan's historical knowledge enabled him to view everything in a realistic perspective, and to illuminate contemporary questions with both parallels and differences in comparison with the past. His mind was cultivated in many disciplines: literature, languages, philosophy and religion, as well as history. Working with him gave great pleasure as well as broadening one's whole life.

Harold loved Oxford and, above all, Balliol, where he always felt at home throughout his long life. He was awarded a first in his Moderations, but the Great War, during which he was wounded three times on active service, prevented him from completing his degree. He also distinguished himself during the 1930s, when, like Eden, he was a staunch opponent of appeasement, and then during the Second World War, when he was Churchill's Minister Resident at allied HQ in North Africa, working alongside Field Marshal Alexander and General Eisenhower. His friendship with Eisenhower stood him in good stead in later years. Harold had nothing but admiration for his fellow soldiers, but, like everyone who has actually seen action, he passionately hated war itself.

Harold Macmillan cared nothing for other people's backgrounds, and judged them by their intelligence and their character. His social policies were informed by his own generous spirit and unquenchable desire to help the underdog, and to ensure that everyone in this country had the opportunity of a decent life. His speeches as a maverick and compassionate backbencher in the 1930s gained support for his views when the Conservative Party came to reassess its policies and priorities in the wake of the massive general election defeat of 1945.