Mary Gawthorpe

Mary Gawthorpe, the third of the five children of John Gawthorpe, leather worker in Leeds, and Anne Mountain, was born at 5 Melville Street, on 12th January 1881. Her mother had done well at school but her family was extremely poor so from the age of ten had to work in the local textile mill. She had wanted to be a teacher and was determined to make sure her daughter finished her education.

At the age of thirteen Mary became a pupil teacher in the local Church of England school. Annie wanted her daughter to go to college but family finances meant that this was not possible. Instead, Mary worked during the day and studied in the evening and at weekends. Mary qualified as a schoolteacher just before her twenty-first birthday.

In 1901 Mary became friendly with Tom Garrs, a compositor on the Yorkshire Post. Tom was an active member of the Independent Labour Party and Mary began going to meetings with him. Mary Gawthorpe became converted to socialism and she soon developed a reputation as an extremely good public speaker. Mary also became a leading figure in the Leeds branch of the National Union of Teachers.

Mary Gawthorpe was a strong supporter of women's rights and with the help of her friends, Isabella Ford, and Ethel Annakin formed a Leeds branch of the Nation Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Mary was also active in the Women's Labour League. However, Mary gradually became disillusioned with the Labour Party's failure to organize men to help win the vote for women. In February 1906, Mary met Christabel Pankhurst after she spoke at a meeting in Leeds. Christabel told Mary that: "The further one goes the plainer one sees that men (even Labour men) think more of their own interests than of ours."

Mary joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in October 1905 after reading about the arrest and imprisonment of Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney in Manchester. Tom Garrs disagreed with the militant activities of the WSPU and as a result of this disagreement, the couple parted.

In 1906 Mary gave up her job as a teacher and became the full-time organizer of the WSPU in Leeds. In October she was arrested with Dora Montefiore and Minnie Baldock during a demonstration outside the House of Commons and was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. After being released from Holloway Prison she became one of the WSPU's main speakers at rallies and demonstrations.

Mary suffered from poor health and in February 1907 she was operated on by Louisa Garrett Anderson for appendicitis. After leaving hospital she spent her convalescence with Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence at their home in Surrey. They also took Mary and Annie Kenney to Italy.

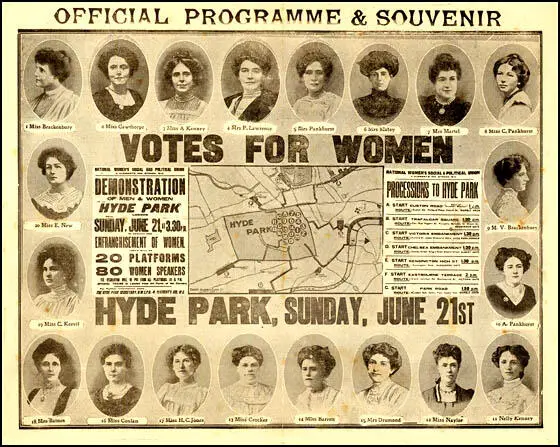

The WSPU organised a mass meeting to take place on 21 June 1908 called Women's Sunday at Hyde Park. The leadership intended it "would out-rival any of the great franchise demonstrations held by the men" in the 19th century. Sunday was chosen so that as many working women as possible could attend. It is claimed that it attracted a crowd of over 300,000. At the time, it was the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. Speakers included Mary Gawthorpe, Gladice Keevil, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Jennie Baines, Rachel Barrett, Marie Brackenbury, Georgina Brackenbury, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Marie Naylor, Flora Drummond and Edith New.

Mary Gawthorpe also organised another successful rally at Heaton Park in Manchester that drew over 150,000 people. Her friend, Sylvia Pankhurst commented: "Mary Gawthorpe was a winsome merry creature, with bright hair and laughing hazel eyes, a face fresh and sweet as a flower, the dainty ways of a little bird, and having with all a shrewd tongue and so sparkling a fund of repartee, that she held dumb with astonished admiration, vast crowds of big, slow-thinking workmen and succeeded in winning to good-tempered appreciation the stubbornness opponents." Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy added: "Mary Gawthorpe... is a splendid speaker, full of humour, brilliant and lucid."

In 1909 Mary Gawthorpe heckled a speech given by Winston Churchill. Mary was badly beaten by stewards at the meeting and suffered severe internal injuries. Mary was also imprisoned several times while working for the WSPU. Hunger strikes and force-feeding badly damaged her health and in 1912 she had to abandon her active involvement in the movement.

Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999) has pointed out: "She (Mary Gawthorpe) went to Manchester to implement there a WSPU decision to hold large meetings in the principle cities in order to capitalize on the publicity and success of Hyde Park. She stayed as chief organizer for the WSPU in Lancashire until ill-health forced her to retire at the end of September 1910."

In March 1911 Dora Marsden and her close friend, Grace Jardine, went to work for the Women's Freedom League newspaper, The Vote. Marsden attempted to persuade the WFL to finance a new feminist journal. When this proposal was refused, Marsden left the journal. She now joined forces with Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe to establish her own journal. Charles Granville, agreed to become the publisher. On 23rd November, 1911, they published the first edition of The Freewoman.

Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication". Edgar Ansell commented that it was "a disgusting publication... indecent, immoral and filthy."

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Edmund Haynes, Catherine Gasquoine Hartley, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

The most controversial aspect of the The Freewoman was its support for free-love. On 23rd November, 1911 Rebecca West wrote an article where she claimed: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly."

Dora Marsden argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, the wife of George Bernard Shaw, wrote to Dora Marsden "though there has been much I have not agreed with in the paper", The Freewoman was nevertheless a "valuable medium of self-expression for a clever set of young men and women". However, Olive Schreiner disagreed and argued that the debates about sexuality were inappropriate and revolting in a publication of "the women's movement". Frank Watts wrote a letter to the journal that if women really wanted to discuss sex "then it must be admitted by sane observers that man in the past was exercising a sure instinct in keeping his spouse and girl children within the sheltered walls of ignorance."

By the summer of 1912 Dora Marsden had become disillusioned with the parliamentary system and no longer considered it important to demand women's suffrage: "The politics of the community are a mere superstructure, built upon the economic base... even though Mr. George Lansbury were Prime Minister and every seat in the House occupied by Socialist deputies, the capitalist system being what it is they would be powerless to effect anything more than the slow paced reform of which the sole aim is to make men and masters settle down in a comfortable but unholy alliance... the capitalists own the states. A handful of private capitalists could make England, or any other country, bankrupt within a week."

This article brought a rebuke from H. G. Wells: That you do not know what you want in economic and social organization, that the wild cry for freedom which makes me so sympathetic with your paper, and which echoes through every column of it, is unsupported by the ghost of a shadow of an idea how to secure freedom. What is the good of writing that economic arrangements will have to be adjusted to the Soul of Man if you are not prepared with anything remotely resembling a suggestion of how the adjustment is to be affected?"

Mary Gawthorpe also criticised Dora Marsden for her what she called her "philosophical anarchism". She told her that she "was not really an anarchist at all" but one who believed in rank, with herself at the top. Mary added: "Intellectually you have signed on as a member of the coming aristocracy. Free individuals you would have us be, but you would have us in our ranks... I watch you from week to week governing your paper. You have your subordinates. You say to one go and she goes, to another come, and she comes."

During this period Dora Marsden developed loving relationships with several women, including Mary Gawthorpe, Rona Robinson, Grace Jardine and Harriet Shaw Weaver. In her letters to these women she often referred to them as "sweetheart". Her biographer, Les Garner, has argued: "Whether any of her friendships with women were sexual cannot be determined - certainly they were close and certainly too, Dora's personality and fragile beauty inspired many endearing comments from her friends. She appeared to have a special and unique quality that inspired devotion, if not awe, in some women.... Whether Dora was gay in the modern sense is unknown. There is no concrete evidence to support such a claim."

In March 1912, Mary Gawthorpe was unable to continue working as co-editor of The Freewoman. Marsden wrote in the journal that "we earnestly hope that the coming months will see her restored to health". Although Mary was ill, she had not resigned on health grounds, but because of what she claimed was "Dora's bullying" and her "philosophical anarchism". Gawthorpe returned all Dora's letters and asked her not to write again: "The sight of your letters I am obliged to confess turns me white with emotion and I have acute heart attacks following on from that."

Mary Gawthorpe's health gradually recovered and in 1916 she emigrated to the United States. She soon became active in the National Woman's Suffrage Party in New York City. After American women won the vote, Mary became involved in the trade union movement and in 1920 became a full-time official of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union.

On 19th July 1921 Mary married John Sanders and became an American citizen. As Sandra Stanley Holton has pointed out: "Throughout her life she retained her single name. She made a brief return to Britain in 1933, and was also in contact with the Suffragette Fellowship in these years. Little is known of her life after this date, though some of her surviving correspondence from the 1950s and 1960s shows that she remained keenly interested in political issues, and was still in touch with movements in Britain, including the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament."

In 1962 Mary Gawthorpe published Up Hill to Holloway, the story of her life up to her release from prison in November 1906. She died at her home in Long Island on 12th March 1973.

Primary Sources

(1) In her book The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement (1931), Sylvia Pankhurst described Mary Gawthorpe as being one of the most important figures in the women's movement.

Mary Gawthorpe was a winsome merry creature, with bright hair and laughing hazel eyes, a face fresh and sweet as a flower, the dainty ways of a little bird, and having with all a shrewd tongue and so sparkling a fund of repartee, that she held dumb with astonished admiration, vast crowds of big, slow-thinking workmen and succeeded in winning to good-tempered appreciation the stubbornness opponents.

(2) Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence joined the Women's Social and Political Union in 1905. In her book My Part in a Changing World (1938) she described some of the leading personalities in the WSPU at that time.

Christabel was cut out for public life. Her chosen career, that of Barrister-at-law, had been checked by the refusal of the Benchers of Lincoln's Inn to admit a woman as a student, so that the career of a political pioneer offered to her the finest kind of self-expression. Like all the Pankhursts she had great courage. She had a cool, logical mind, and a quick, ready wit. She was young and attractive, graceful on the platform, with a singularly clear and musical voice. She had none of Sylvia's passion of pity - on the contrary, she detested weakness, which was discouraged in her presence.

Sylvia Pankhurst had given up career and status to go amongst the masses of the people in order to instruct them, and so to prepare the ground for the revolution, which they believed, would some day take place. There was a certain infantile look about her, because her face had the roundness and smoothness of a child. Quiet and shy in those days, she had surprised her friends by one brilliant success after another.

Annie Kenney seemed to have a whole-hearted faith in the goodness of everybody that she met… Her strength lay in complete surrender of mind and soul to a single idea and to the incarnation of that idea in a single person. She was Christabel's devotee in a sense that was mystical; I mean she neither gave nor looked to receive any expression of personal tenderness: her devotion took the form of unquestioning faith and absolute obedience.

Mary Gawthorpe was a Yorkshire girl, very tiny, with a winsome face sparkling with animation, and with laughing, golden eyes. She had a gift of ready wit and repartee which, linked with imperturbable good humour, made her irresistible to the crowd.

(3) In January 1910, Constance Lytton visited WSPU members in prison.

Mary Gawthorpe was ill with an internal complaint. Mary said, with tears in her eyes, as she threw her arms round me: "Oh, and these are women quite unknown - nobody knows or cares about them except their own friends. They go to prison again and again to be treated like this, until it kills them!"

(4) Rebecca West, Time and Tide (16th July, 1926)

Dora Marsden conceived the idea of starting the Freewoman because she was discontented with the limited scope of the suffragist movement. She felt that it was restricting itself too much to the one point of political enfranchisement and was not bothering about the wider issues of Feminism. I think she was wrong in formulating this feeling as an accusation against the Pankhursts and suffragettes in general, because they were simply doing their job, and it was certainly a whole time job. But there was equally certainly a need for someone to stand aside and ponder on the profounder aspects of Feminism. In this view she found a supporter in Mary Gawthorpe, a Yorkshire woman who had recently been invalided out of the suffrage movement on account of injuries sustained at the hands of stewards who had thrown her out of a political meeting where she had been interrupting Mr. Winston Churchill. Mary Gawthorpe, was a merry militant saint who had travelled round the provinces, living in dreary lodgings on $15 or $20 a week, speaking several times a day at outdoor meetings, and suffering fools gladly (which I think she found the hardest job of all), when trying to convert the influential Babbits of our English zenith cities. Occasionally she had a rest in prison, which she always faced with a sparrow-like perkiness. She had wit and common sense and courage, and each to the point of genius. She lives in the United States now, but her inspiration still lingers over here on a whole generation of women.