Strange Fruit

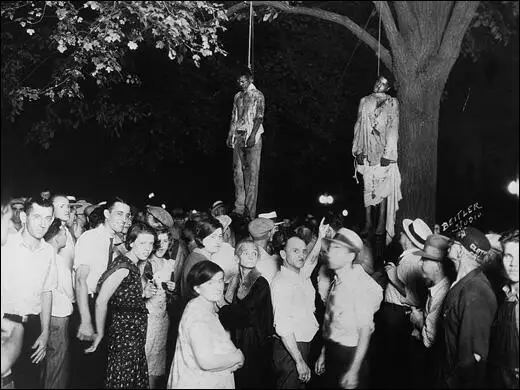

In 1937 Abe Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from New York, saw a photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. Meeropol later recalled how the photograph "haunted me for days" and inspired the writing of the poem, Strange Fruit. Meeropol, a member of the American Communist Party, using the pseudonym, Lewis Allan, published the poem in the New York Teacher and later, the Marxist journal, New Masses.

The sociologist, Arthur Franklin Raper was commissioned in 1930 to produce a report on lynching. He discovered that "3,724 people were lynched in the United States from 1889 through to 1930. Over four-fifths of these were Negroes, less than one-sixth of whom were accused of rape. Practically all of the lynchers were native whites. The fact that a number of the victims were tortured, mutilated, dragged, or burned suggests the presence of sadistic tendencies among the lynchers. Of the tens of thousands of lynchers and onlookers, only 49 were indicted and only 4 have been sentenced."

After seeing Billie Holiday perform at the club, Café Society, in New York City, Meeropol showed her the poem. Holiday liked it and after working on it with Sonny White turned the poem into the song, Strange Fruit. The record made it to No. 16 on the charts in July 1939. However, the song was denounced by Time Magazine as "a prime piece of musical propaganda" for the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).

Meeropol remained active in the American Communist Party and after the execution of Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg he adopted their two sons, Michael Meeropol and Robert Meeropol. He taught at the De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx for 27 years, but continued to write songs, including the Frank Sinatra hit, The House I Live In. (1945). A song that is still relevant to the United States today.

Primary Sources

(1) Abe Meeropol, Strange Fruit, (1939)

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

(2) Billie Holiday, Lady Sings the Blues (1956)

The germ of the song was in a poem written by Lewis Allen. When he showed me that poem, I dug it right off. It seemed to spell out all the things that had killed Pop (Holliday's father had died of pneumonia in 1937 after several segregated southern hospitals refused to treat him). Allen, too, had heard how Pop died and of course was interested in my singing. He suggested that Sonny White, who had been my accompanist, and I turn it into music. So the three of us got together and did the job in about three weeks.

(3) Samuel Grafton, New York Post (October 1939)

This is about a phonograph record which has obsessed me for two days. It is called Strange Fruit and it will, even after the tenth hearing, make you blink and hold to your chair. Even now, as I think of it, the short hair on the back of my neck tightens and I want to hit somebody. I know who, too. If the anger of the exploited ever mounts high enough in the South, it now has its Marseillaise.

(4) David Margolik, Vanity Fair (September 1998)

In interviews, Holiday said that whenever she performed Strange Fruit in the South there was trouble. She told one newspaper that she was driven out of Mobile, Alabama, for trying to sing it. In fact, Holiday made few southern tours, and there's little evidence that she sang Strange Fruit when she did.

Claims that the song was banned from the radio are equally hard to document, but not hard to believe; radio stations played few records then, and rarely anything controversial. "WNEW [in New York] has been trying to get up the courage to allow Billie Holiday, singing at Café Society, to render the anti-lynching song - Strange Fruit Growing on the Trees Down South - on one of the night spot's regular broadcasts," the New York Post reported in November 1939. "Station turned thumbs down a week ago, but approved the number for last night's airing. Then it said 'no' again, but has agreed to let Billie sing it tonight at 1 o'clock." According to one published report, the song was also banned from the BBC.

(5) Caryl Phillips, The Guardian (18th August, 2007)

In early 1983, I was in Alabama, being driven the 130 miles from Birmingham to Tuskegee by the father of one of the four girls who had been killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing of 1963. Chris McNair is a gregarious and charismatic man who, at the time, was running for political office; he was scheduled to make a speech at the famous all-black college, Tuskegee Institute. That morning, as he was driving through the Alabama countryside, he took the opportunity to quiz me about my life and nascent career as a writer. He asked me if I had published any books yet, and I said no. But I quickly corrected myself and sheepishly admitted that my first play had just been published. When I told him the title he turned and stared at me, then he looked back to the road. "So what do you know about lynching?" I swallowed deeply and looked through the car windshield as the southern trees flashed by. I knew full well that "Strange Fruit" meant something very different in the US; in fact, something disturbingly specific in the south, particularly to African Americans. A pleasant, free-flowing conversation with my host now appeared to be shipwrecked on the rocks of cultural appropriation.

I had always assumed that Billie Holiday composed the music and lyrics to Strange Fruit. She did not. The song began life as a poem written by Abel Meeropol, a schoolteacher who was living in the Bronx and teaching English at the De Witt Clinton High School, where his students would have included the Academy award-winning screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, the playwright Neil Simon, and the novelist and essayist James Baldwin. Meeropol was a trade union activist and a closet member of the Communist Party; his poem was first published in January 1937 as Strange Fruit, in a union magazine called the New York School Teacher. In common with many Jewish people in the US during this period, Meeropol was worried (with reason) about anti-semitism and chose to publish his poem under the pseudonym "Lewis Allan", the first names of his two stillborn children....

On that hot southern morning, as Chris McNair drove us through the Alabama countryside, I knew little about the background to the Billie Holiday song, and I had never heard of Lillian Smith. After a few minutes of silence, McNair began to talk to me about the history of violence against African-American people in the southern states, particularly during the era of segregation. This was a painful conversation for a man who had lost his daughter to a Ku Klux Klan bomb. I had, by then, confessed to him that my play had nothing to do with the US, with African Americans, with racial violence, or even with Billie Holiday. And, being a generous man, he had nodded patiently, and then addressed himself to my education on these matters. However, I did have some knowledge of the realities of the south - not only from my reading, but from an incident a week earlier. While I was staying at a hotel in Atlanta, a young waiter had warned me against venturing out after dark because the Klan would be rallying on Stone Mountain that evening, and after their gathering they often came downtown for some "fun". However, as the Alabama countryside continued to flash by, I understood that this was not the time to do anything other than listen to McNair.

That afternoon, in a packed hall in Tuskegee Institute, McNair began what sounded to me like a typical campaign speech. He was preaching to the converted, and a light shower of applause began to punctuate his words as he hit his oratorical stride. But then he stopped abruptly, and he announced that today, for the first time, he was going to talk about his daughter. "I don't know why, because I've never done this before. But Denise is on my mind." He studiously avoided making eye contact with me, but, seated in the front row, I felt uneasily guilty. A hush fell over the audience. "You all know who my daughter is. Denise McNair. Today she would have been 31 years old."