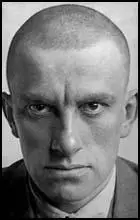

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky was born in Bagdadi, Georgia, on 7th July, 1893. At the age of fourteen Mayakovsky took part in socialist demonstrations at the town of Kutaisi.

In 1906 Mayakovsky moved to Moscow with his mother. He joined the illegal Social Democratic Labour Party and over the next ten years was arrested several times and spent eleven months in prison. While in Butyrka Prison in 1909, he began to write poetry.

Eugene Lyons, the author of Assignment in Utopia (1937), has pointed out: "Mayakovsky had begun his literary life under tsarism as an imagist. He welcomed the revolution as unshackling creative energies and giving a right of way to literary experiment. But he accepted also its profounder purposes as social change. Unlike a good many other poets, he harnessed his Muse to the needs of the new era not only willingly but with loud hurrahs of enthusiasm."

On his release from prison in 1909 he attended Moscow Art School where he formed the Cubo-Futurist Group with David Burlyuk. Mayakovsky attempted to join the Russian Army on the outbreak of the First World War. Instead he found employment at the Petrograd Military Automobile School as a draftsman. During this period he completed two major poems, A Cloud in Trousers (1915) and The Backbone Flute (1916), a poem that dealt with his affair with a married woman, Lilya Brik and the trauma of the war.

Mayakovsky fully supported the October Revolution and this inspired such poems as Ode to Revolution (1918) and Left March (1919). He also contributed drawings and text for hundreds of propaganda posters calling for a Bolshevik victory in the Civil War. He also wrote a 3,000 line elegy on the death of Lenin. Mitchell Abidor has argued that: "Mayakovsky... put his considerable talents at the service of the new state. He produced posters, films and political poems in order to reach as broad a mass as possible. The death of Lenin profoundly moved him, and he gave countless readings in factories, clubs, and at party meetings around the Soviet Union."

Eugene Lyons met him in Moscow and described him as "a tall, broad-shouldered fellow who dressed like an apache, Mayakovsky gloried in tough-guy gestures and wore the adjective proletarian like a challenge to the world. But there was too much bluster in his attitude to be wholly convincing. In an occasional nostalgic line of rare beauty, in a casual sigh in the very midst of some blood-and-thunder invocation to duty, he betrayed the suppressed lyricist and romanticist."

Mayakovsky became increasingly critical of the Soviet government under Joseph Stalin. His plays, The Bedbug (1929) and The Bathhouse (1930) were thinly disguised satires on Stalin's authoritarianism. As a result he was attacked as a follower of Leon Trotsky. Increasingly disillusioned with communism and denied a visa to travel abroad, Vladimir Mayakovsky committed suicide in Moscow on 14th April, 1930.

In his suicide note he wrote: “Do not blame anyone for my death and please do not gossip. The deceased terribly dislike this sort of thing. Mamma, sisters and comrades, forgive me - this is not a way out (I do not recommend it to others), but I have none other. Lily - love me…Comrades of VAPP - do not think me weak-spirited. Seriously - there was nothing else I could do.”

Primary Sources

(1) Vladimir Mayakovsky, Our March (1917)

Beat the squares with the tramp of rebels!

Higher, rangers of haughty heads!

We'll wash the world with a second deluge,

Now’s the hour whose coming it dreads.

Too slow, the wagon of years,

The oxen of days — too glum.

Our god is the god of speed,

Our heart — our battle drum.

Is there a gold diviner than ours?

What wasp of a bullet us can sting?

Songs are our weapons, our power of powers,

Our gold — our voices — just hear us sing!

Meadow, lie green on the earth!

With silk our days for us line!

Rainbow, give color and girth

To the fleet-foot steeds of time.

The heavens grudge us their starry glamour.

Bah! Without it our songs can thrive.

Hey there, Ursus Major, clamour

For us to be taken to heaven alive!

Sing, of delight drink deep,

Drain spring by cups, not by thimbles.

Heart step up your beat!

Our breasts be the brass of cymbals.

(2) Vladimir Mayakovsky, The Call to Account (1917)

The drum of war thunders and thunders.

It calls: thrust iron into the living.

From every country

slave after slave

are thrown onto bayonet steel.

For the sake of what?

The earth shivers

hungry

and stripped.

Mankind is vapourised in a blood bath

only so

someone

somewhere

can get hold of Albania.

Human gangs bound in malice,

blow after blow strikes the world

only for

someone’s vessels

to pass without charge

through the Bosporus.

Soon

the world

won’t have a rib intact.

And its soul will be pulled out.

And trampled down

only for someone,

to lay

their hands on

Mesopotamia.

Why does

a boot

crush the Earth — fissured and rough?

What is above the battles’ sky -

Freedom?

God?

Money!

When will you stand to your full height,

you,

giving them your life?

When will you hurl a question to their faces:

Why are we fighting?

(3) Vladimir Mayakovsky, Past One O’Clock (1930)

Past one o’clock. You must have gone to bed.

The Milky Way streams silver through the night.

I’m in no hurry; with lightning telegrams

I have no cause to wake or trouble you.

And, as they say, the incident is closed.

Love’s boat has smashed against the daily grind.

Now you and I are quits. Why bother then

To balance mutual sorrows, pains, and hurts.

Behold what quiet settles on the world.

Night wraps the sky in tribute from the stars.

In hours like these, one rises to address

The ages, history, and all creation.

(4) Eugene Lyons, Assignment in Utopia (1937)

The tragedy of that stifled, gritty period in Soviet art was underlined, for me at any rate, by the suicide of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Mayakovsky had begun his literary life under tsarism as an imagist. He welcomed the revolution as unshackling creative energies and giving a right of way to literary experiment. But he accepted also its profounder purposes as social change. Unlike a good many other poets, he harnessed his Muse to the needs of the new era not only willingly but with loud hurrahs of enthusiasm.

If Sergei Yessenin, the lyric playboy of the emotions, represented the "pure" poet, free and singing, Mayakovsky made of himself the disciplined poet, who had tamed his talents and used them like domestic animals to do the work of the revolution. Yessenin wrote a farewell note in his own blood and hung himself in 1925. Mayakovsky wept over that death but castigated that futile gesture. "In this life it is easy to die," he wrote, "to build life is hard."

Mayakovsky lived, lived lustily and fully, in the day-to-day tasks of the harsh years. He jeered at the "Russian soul" and romantic private emotions. He hammered out hymns to ruthlessness, to machinery, to the G.P.U. that was his country's new fate, and he bellowed his disdain for the romanticists and esthetes. His poems were staccato and shrill, he shrank from no vulgarity, he dragged the moon and the stars down to earth as raw stuff for the Five Year Plan.

A tall, broad-shouldered fellow who dressed like an apache, Mayakovsky gloried in tough-guy gestures and wore the adjective "proletarian" like a challenge to the world. But there was too much bluster in his attitude to be wholly convincing. In an occasional nostalgic line of rare beauty, in a casual sigh in the very midst of some blood-and-thunder invocation to duty, he betrayed the suppressed lyricist and romanticist.

Some of his readers lacked the sharpness of ear to detect the weeping under his Homeric laughter; others pretended not to hear. He was accepted as the hard-boiled voice of a hard-boiled epoch.

And suddenly in April, 1930, the news was out that Mayakovsky had killed himself; more shocking than that, killed himself because of a silly love affair with a married actress. He left a shamefacedly flippant note to his comrades on RAPP, indicating that his "love-boat" had foundered on the shoals of reality.

The man who had made of himself a symbol of impersonal, collectivized emotion, whose derision of bourgeois parlor-and-bedroom dramas still echoed all around him, died like a Dostoievsky character. "I know this is not the way out," he apologized, "I recommend it to no one - but I have no other course."

Curiously enough, no one thought it strange. In its subconscious mind, the Russian people had never really believed his bluster. The denial of the importance of individual happiness or individual pain enforced by the Kremlin was only on the surface. The petty literary dictators pretended to regard the suicide as a sort of fit of insanity unrelated to the real Mayakovsky; they scolded him for his despair. Yet they knew what the Russian people felt instinctively: that Mayakovsky's suicide was the answer to the dehumanized brutalities which he had himself celebrated.

(5) Vladimir Mayakovsky, suicide note (12th April, 1930)

Do not blame anyone for my death and please do not gossip. The deceased terribly dislike this sort of thing. Mamma, sisters and comrades, forgive me - this is not a way out (I do not recommend it to others), but I have none other. Lily - love me…Comrades of VAPP - do not think me weak-spirited. Seriously - there was nothing else I could do.