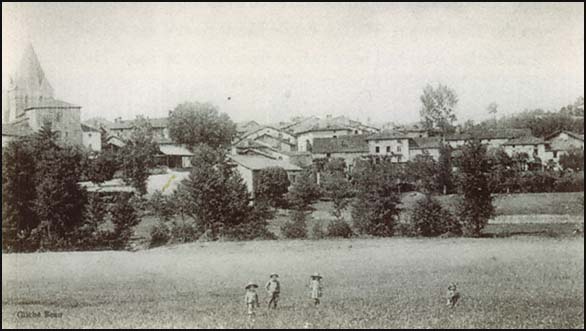

Oradour-sur-Glane

In the spring of 1942, communist militants, acting independently of the leadership of the French Communist Party, organized the first Maquis in the Limousin and the Puy-de-Dôme. Marquis groups were established in other regions of France. As the Maquis grew in strength it began to organize attacks on German forces.

In the Limousin, the Marquis were led by the Communist militant, Georges Guingouin. At this time Guingouin was not supplied with any weapons. Therefore their main method of resisting the German Army was sabotage. This included attacks on bridges, telephone lines and railway tracks.

.

The Maquis also provided aid and protection to refugees, immigrants, Jews, and others threatened by the Vichy and the German authorities. They also helped to get Allied airman, whose aircraft had been shot down in France, to get back to Britain.

In March 1944, the German Army began a campaign of repression throughout France. This included a policy of reprisals against civilians living in towns and villages close to the scene of attacks carried out by members of the French Resistance. As one official wrote on 15th April, 1944 that the authorities "wanted to strike fear into the population and change their opinion by showing them that the evils they were suffering were the direct consequence of the existence of the marquis and that they had made the mistake of tolerating them."

On 5th June, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower asked the BBC sent out coded messages to the resistance asking them to carry out acts of resistance during the D-day landings in order to help Allied forces establish a beachhead on the Normandy coast. The Maquis responded to this request and on 7th June, a unit attacked the German garrison at Tulle. The following day the arrival of reinforcements forced the unit to withdraw. The German losses were considerable, it was reported that 37 soldiers were killed and another 25 were wounded.

On the 9th June, the Schutzstaffel (SS) hanged 99 men from the balconies, trees, and bridges along the main street of Tulle. Another 149 were deported to Germany. Later that day another 67 were murdered in Argenton. The following day German soldiers began encircling the village of Oradour-sur-Glane. A unit of 120 soldiers from the Waffen SS tank division entered the village and instructed everyone to assemble in the central marketplace. Other soldiers in armored cars rounded up men and women working in nearby farms and fields.

.

At about three o'clock the soldiers separated the women and children from the men. They were taken to the church and locked in. Major Otto Dickman, announced that the SS knew that the village was hiding arms and munitions for the French Resistance. Dickman then told the mayor, Paul Desourteaux, to select hostages from among those assembled in the marketplace. The mayor refused, offering himself and his sons instead.

Dickman rejected Desourteaux's offer and ordered that all the men be divided into groups and moved them to various barns and garages in the village. The SS soldiers then opened fire on the men. The only ones to survive were five young men from a group of 62 taken to the Laudy barn. This included Marcel Darthout: "We felt the bullets, which brought me down. Everyone was on top of me. And they were still firing. And there was shouting. And crying. I had a friend who was lying on top of me and who was moaning. And then it was over. No more shots. And they came at us, stepping on us. And with a rifle they finished us off. They finished off the buddy who was on top of me. I felt it when he died."

.

At five o'clock two German soldiers entered the church and placed a large chest on the altar. They walked out, laying out a long fuse as they went, which they lit before shutting the door. A few seconds later the chest exploded. Some managed to survive the blast but were shot dead by the soldiers as they scrambled out of the bombed building. Only Marguerite Rouffanche managed to get out of the church and escape the bullets being fired by the SS soldiers. Although she was wounded she managed to hide until the Germans left the village.

Sarah Farmer, the author of Martyred Village (1999) later explained: "Only one person managed to save herself from the conflagration. Marguerite Rouffanche, a forty-seven-year-old woman, had been part of a group that pushed back into the sacristy in search of fresh air. As the church burned, she crawled behind the altar and found a stool used for lighting candles. She managed to climb up and out the window. She dropped three meters to the ground below. Looking up, Madame Rouffanche saw that she had been followed by a young woman with a baby. The young woman handed down her baby before jumping, but all three were caught in a hail of machine-gun fire. Mother and child were killed; wounded, Madame Rouffanche was able to crawl into the garden of the presbytery, where she hid among rows of peas."

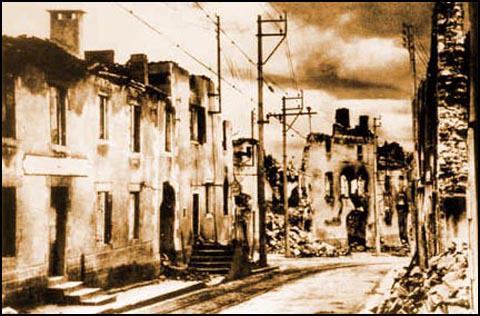

The Germans then destroyed Oradour-sur-Glane. A total of 642 people were killed during the SS operation. This included 393 people living in the village, 167 people from neighbouring villages, 33 people from Limoges, and 25 others from different parts of the Haute-Vienne. Around 80 residents of Oradour survived. This included the five men from the Laudy barn, Marguerite Rouffanche from the church, 28 people who managed to hide during the roundup and 36 others who happened to be away for the day. Another 12 men were in Germany as part of Vichy's compulsory labour service.

.

Local hamlets also suffered high losses. Eight children of Le Mas du Puy attended the school at Oradour. Four mothers, concerned that their children had not come home from school, had gone to Oradour to look for them. They died with their children in the church.

In 1946 the French government decided to preserve the ruins of Oradour-sur-Glane. The forty acres of crumbling buildings became a martyred village. A testament of French suffering under the German occupation and an example of Nazi barbarism.

Primary Sources

(1) Lawrence Olivier, The Word at War (1973)

Down this road, on a summer day in 1944. The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road and they were driven into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War.

(2) Marcel Darthout was one of the men who survived the shooting in the Laudy Barn. Darthout was interviewed about his experiences in 1988.

We felt the bullets, which brought me down. Everyone was on top of me. And they were still firing. And there was shouting. And crying. I had a friend who was lying on top of me and who was moaning. And then it was over. No more shots. And they came at us, stepping on us. And with a rifle they finished us off. They finished off the buddy who was on top of me. I felt it when he died.

(3) Sarah Farmer, Martyred Village (1999)

The chest exploded, releasing clouds of suffocating smoke and blowing out some of the church windows. In the ensuing chaos, the soldiers opened the door and sprayed the group with gunfire. They piled flammable material on some of the bodies, set a bonfire with the church pews, and abandoned the building.

Only one person managed to save herself from the conflagration. Marguerite Rouffanche, a forty-seven-year-old woman, had been part of a group that pushed back into the sacristy in search of fresh air. As the church burned, she crawled behind the altar and found a stool used for lighting candles. She managed to climb up and out the window. She dropped three meters to the ground below. Looking up, Madame Rouffanche saw that she had been followed by a young woman with a baby. The young woman handed down her baby before jumping, but all three were caught in a hail of machine-gun fire. Mother and child were killed; wounded, Madame Rouffanche was able to crawl into the garden of the presbytery, where she hid among rows of peas.

(4) Report written by an agent of the French domestic security service (16th June, 1944)

It was not until Monday, the twelfth of June, that one learned that on Saturday the tenth, in the course of the afternoon, the entire bourg of Oradour had been prey to fire and that the whole population had been shot and burned following police operations undertaken by the occupying authorities. Emotion gave way to horror and consternation when one knew with certainty that many women and children died a horrible death in the burning of the church.

(5) Ce Soir (22nd August, 1944)

For four years we have all lived in horror, we have all been used to hearing in low voices in our families, among friends, the sinister news of prisoners shot, whole buildings where inhabitants, chosen at random as hostages, have been savagely slaughtered, farms and their inhabitants burned: it was our daily news. Nonetheless, certain dreadful massacres which go beyond the Occupier's habitual savagery have sorrowfully made several French villages famous. The names of Chateaubriant, Oradour-sur-Glane, Ascq are on all lips.

(6) Jacques Delarue, Oradour (1945)

The drama of Oradour eclipsed all the other crimes of the "Das Reich" Division. The name of the martyred Limousin village became a symbol, the image of crime and of suffering, and that is understandable. But this attitude, in isolating the crime from its general context, that is to say the wave of crimes that surrounded it, the long succession of murders, assassinations, arson, and destruction, which this account has tried to reconstruct, has caused one to forget all these other crimes and made of Oradour an exceptional event, an involuntary excess due to the war, when it was only the application, more total and complete, of the daily methods of the "DAs Reich" Division.