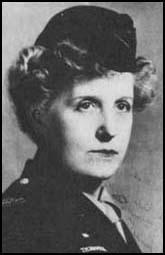

Sigrid Schultz

Sigrid Schultz, the daughter of a portrait painter from Norway, was born in Chicago in 1893. Educated in France and Germany, she joined the Chicago Tribune in 1919. Seven years later she had become bureau chief in Berlin. It is believed that she was the first woman in the world to hold such a position in a major news bureau.

Schultz interviewed Adolf Hitler several times and soon became convinced that his foreign policies would eventually lead to war. On one occasion Hitler told her that: "You cannot understand the Nazi movement, because you think with your head and not with your heart." In order to protect her life, Schultz's articles attacking Hitler were published under the name John Dickson.

Schultz was injured during a bombing raid of Berlin. After receiving medical treatment in the United States Schultz attempted to return to Germany in August, 1941, but the Nazi government refused to let her enter. Instead she made a nationwide lecture tour and wrote the book, Germany Will Try It Again (1944).

In 1944 Sigrid Schultz worked a a war correspondent for McCall's and Liberty magazines. She accompanied the US Army when it landed in Normandy in 1944. She also reported on the liberation of France and the advance into Nazi Germany. Schultz was one of the first journalists to visit Buchenwald and covered the Nuremberg War Trials.

After the war Schultz retired to her family home to take care of her ill mother. Sigrid Schultz continued to write and was working on a history of Anti-Semitism in Germany when she died in 1980.

Primary Sources

(1) Sigrid Schultz, Chicago Tribune (13th July, 1939)

Communism, Soviet Russia and Dictator Stalin were called the arch enemies of civilization when Hitler was advancing toward supreme power. Hatred of communism and the faith of the bourgeois that he would save from communism helped him become master of Germany.

Today England is being proclaimed as World Enemy No.1. She is accused of usurping the rights of small nations, of opposing Germany's "right to be the first power in the world."

Hatred of England is simmering or blazing in Japan, India, Arabia, Africa, Ireland, Russia, and England's ally, France. It is being fanned systematically by Nazi agents throughout the world.

Hitler, it is said, hopes to use this hatred to establish Germany as the most powerful nation in the world, the same as he used the German citizen's hatred of communism to establish his rule in Germany.

Friendship with Soviet Russia, or at least an understanding with her, can prove a powerful weapon in Germany's campaign "to force England to her knees," diplomatic sources declare.

The Germans figure that the English are so terrified of the possible formation of a Soviet-German bloc that Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax will again go to Germany and offer all the concessions the Germans want. If the British fail to respond to the threat, the Germans argue that they can still get enough raw materials and money out of Russia to make the deal worth while.

(2) William L. Shirer, reviewing Sigrid Schultz's book, Germany Will Try It Again (1944)

No other American correspondent in Berlin knew so much of what was going on behind the scenes as did Sigrid Schultz.

(3) Lilya Wagner, Women War Correspondents of World War II (1981)

Sigrid was one of the first U.S. journalists to predict the coming conflict - World War II. She had covered central Europe from 1916, and would do so until 1941. She interviewed many top Nazi leaders and warned early of the dangers they represented to world peace and the lives of Jews in Hitler's Third Reich.

(4) Frederick S. Voss, Reporting the War: The Journalistic Coverage of World War II (1994)

One of Schultz's great talents lay in cultivating reliable insider news sources, and in 1938 and 1939 the information she gained from her extensive network of German contacts led to a succession of articles for the Tribune that revealed, in sometimes amazing detail, the workings and ambitions of the Third Reich. In the interest of protecting their author from possible reprisals from German authorities, the stories ran under the pseudonym John Dickson, and they carried false European datelines meant to suggest that Dickson was getting his information from sources outside German borders. It was a wise precaution. Running a broad gamut in terms of their subject matter, the articles offered convincing anecdotal proof of the ruthless oppression spawned by the Nazi regime and of its ever-more-ambitious military designs on much of the rest of Europe. If the Nazi establishment had known that Sigrid Schultz was the real author of these stories, it doubtless would have been risky for her to remain in Berlin.