Firestorms

In 1941 Charles Portal of the British Air Staff advocated that entire cities and towns should be bombed. Portal claimed that this would quickly bring about the collapse of civilian morale in Germany. Air Marshall Arthur Harris agreed and when he became head of RAF Bomber Command in February 1942, he introduced a policy of area bombing (known in Germany as terror bombing) where entire cities and towns were targeted.

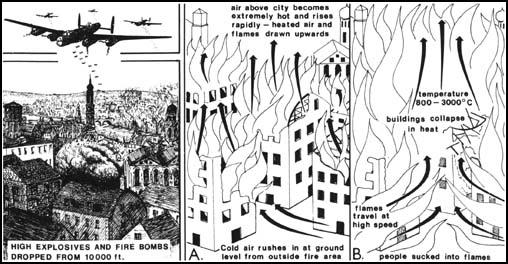

One tactic used by the Royal Air Force and the United States Army Air Force was the creation of firestorms. This was achieved by dropping incendiary bombs, filled with highly combustible chemicals such as magnesium, phosphorus or petroleum jelly (napalm), in clusters over a specific target. After the area caught fire, the air above the bombed area, become extremely hot and rose rapidly. Cold air then rushed in at ground level from the outside and people were sucked into the fire. The most notable examples of this tactic being used was in Hamburg (August, 1943), Dresden (February, 1945) and Tokyo (March 1945).

Primary Sources

(1) Alexander McKee, Dresden 1945: the Devil's Tinderbox (1982)

From a firestorm there is small chance of escape. Certain conditions had to be present, such as the concentration of high buildings and a concentration of bombers in time and space, which produced so many huge fires so rapidly and so close together that the air above them super-heated and drew the flames out explosively. On the enormous scale of a large city, the roaring rush of heated air upwards developed the characteristics and power of a tornado, strong enough to pick up people and such them into the flames.

(2) German report on the firestorm in Hamburg on 24th July, 1943.

Coal and coke supplies stored for the winter in many houses caught fire and could only be extinguished weeks later. Essential services were severely damaged and telephone services were cut early in the attack. Dockyards and industrial installations were severely hit. At mid-day next day there was still a gigantic, dense cloud of smoke and dust hovering over the city which, despite the clear sky, prevented the sun from penetrating through. Despite employment of all available force, big fires could not be prevented from flaring up again and again.

The alternative dropping of block busters (4000 Ib. highcapacity bombs) high explosives, and incendiaries, made fire-fighting impossible, small fires united into conflagrations in the shortest time and these in turn led to the fire storms. To comprehend these one can only analyse them from a physical, meteorological angle. Through the union of a number of fires, the air gets so hot that on account of its decreasing specific weight, it receives a terrific momentum, which in its turn causes other surrounding air to be sucked towards the centre. By that suction, combined with the enormous difference in temperature (600-1000 degrees centigrade) tempests are caused which go beyond their meteorological counterparts

(20-30 centigrades). In a built-up area the suction could not follow its shortest course, but the overheated air stormed through the street with immense force taking along not only sparks but burning timber and roof beams, so spreading the fire farther and farther, developing in a short time into a fire typhoon such as was never before witnessed, against which every human resistance was quite useless.

(3) Major-General Kehrl, report on the firestorm in Hamburg in August, 1943.

Before half an hour had passed, the districts upon which the weight of the attack fell were transformed into a lake of fire covering an area of twenty-two square kilometres. The effect of this was to heat the air to a temperature which at times was estimated to approach 1,000 degrees centigrade. A vast suction was in this way created so that the air "stormed through the streets with immense force, bearing upon it sparks, timber and roof beams and thus spreading the fire still further and further till it became a typhoon such as had never before been witnessed, and against which all human resistance was powerless." Trees three feet thick were broken off or uprooted, human beings were thrown to the ground or flung alive into the flames by winds which exceeded 150 miles an hour. The panic-stricken citizens knew not where to turn. Flames drove them from the shelters, but high-explosive bombs sent them scurrying back again. Once inside, they were suffocated by carbon-monoxide poisoning and their bodies reduced to ashes as though they had been placed in a crematorium, which was indeed what each shelter proved to be.

(4) Adolf Galland, The First and the Last (1970)

A wave of terror radiated from the suffering city and spread through Germany. Appalling details of the great fire was recounted. A stream of haggard, terrified refugees flowed into the neighbouring provinces. In every large town people said: "What happened to Hamburg yesterday can happen to us tomorrow". After Hamburg in the wide circle of the political and the military command could be heard the words: "The war is lost".

(5) Wilhelm Johnen, was a Luftwaffe pilot who attempted to protect Hamburg in August 1943.

A few days later we heard further details of the agony of this badly hit city. The raging fires in a high wind caused terrific damage and the grievous loss of human life out-stripped any previous raids. All attempts to extinguish them proved fruitless and technically impossible. The fires spread unhindered, causing fiery storms which reached heats of 1,000°, and speeds approaching gale force. The narrow streets of Hamburg with their countless backyards were favourable to the flames and there was no escape. As the result of a dense carpet bombing, large areas of the city had been transformed into a single sea of flame within half an hour. Thousands of small fires joined up to become a giant conflagration. The fiery wind tore the roofs from the houses, uprooted large trees and flung them into the air like blazing torches.

The inhabitants took refuge in the air-raid shelters, in which later they were burned to death or suffocated. In the early morning, thousands of blackened corpses could be seen in the burned-out streets. In Hamburg now one thought was uppermost in every mind to leave the city and abandon the battlefield. During the

following nights, until 3rd August 1943, the British returned and dropped on the almost defenceless city about 3,000 block-busters, 1,200 land-mines, 25,000 H.E., 3,000,000 incendiaries, 80,000 phosphorus bombs and 500 phosphorus drums; 40,000 men were killed, a further 40,000 wounded and 900,000 were homeless or missing. This devastating raid on Hamburg had the effect of a red light on all the big German cities and on the whole German people. Everyone felt it was now high time to capitulate before any further damage was done. But the High Command insisted that the 'total war' should proceed. Hamburg was merely the first link in a long chain of pitiless air attacks made by the Allies on the German civilian population.

(6) Margaret Freyer was living in Dresden during the firestorm created on 13th February, 1945.

The firestorm is incredible, there are calls for help and screams from somewhere but all around is one single inferno.

To my left I suddenly see a woman. I can see her to this day and shall never forget it. She carries a bundle in her arms. It is a baby. She runs, she falls, and the child flies in an arc into the fire.

Suddenly, I saw people again, right in front of me. They scream and gesticulate with their hands, and then - to my utter horror and amazement - I see how one after the other they simply seem to let themselves drop to the ground. (Today I know that these unfortunate people were the victims of lack of oxygen). They fainted and then burnt to cinders.

Insane fear grips me and from then on I repeat one simple sentence to myself continuously: "I don't want to burn to death". I do not know how many people I fell over. I know only one thing: that I must not burn.

(7) Otto Sailer-Jackson was a keeper at Dresden Zoo on 13th February, 1945.

The elephants gave spine-chilling screams. The baby cow elephant was lying in the narrow barrier-moat on her back, her legs up in the sky. She had suffered severe stomach injuries and could not move. A 90 cwt. cow elephant had been flung clear across the barrier moat and the fence by some terrific blast wave, and stood there trembling. I had no choice but to leave these animals to their fate.

I had known for one hour now that the most difficult task could ever bring was facing me. "Lehmann, we must get to the carnivores," I called. We did what we had to do, but it broke my heart.

(8) Members of the RAF bombing crews became increasingly concerned about the morality of creating firestorms. Roy Akehurst was a wireless operator who took part in the raid on Dresden.

It struck me at the time, the thought of the women and children down there. We seemed to fly for hours over a sheet of fire - a terrific red glow with thin haze over it. I found myself making comments to the crew: "Oh God, those poor people." It was completely uncalled for. You can't justify it.

(9) Homer Bigart, New York Tribune (16th August, 1945)

The radio tells us that the war is over but from where I sit it looks suspiciously like a rumor. A few minutes ago - at 1:32 a.m. - we fire-bombed Kumagaya, a small industrial city behind Tokyo near the northern edge of Kanto Plain. Peace was not official for the Japanese either, for they shot right back at us.

Other fires are raging at Isesaki, another city on the plain, and as we skirt the eastern base of Fujiyama Lieutenant General James Doolittle's B-29s, flying their first mission from the 8th Air Force base on Okinawa, arrive to put the finishing touches on Kumagaya.

I rode in the City of Saco (Maine), piloted by First Lieutenant Theodore J. Lamb, twenty-eight, of 103-21 Lefferts Blvd, Richmond Hill, Queens, New York. Like all the rest. Lamb's crew showed the strain of the last five days of the uneasy "truce" that kept Superforts grounded.

They had thought the war was over. They had passed most of the time around radios, hoping the President would make it official. They did not see that it made much difference whether Emperor Hirohito stayed in power. Had our propaganda not portrayed him as a puppet? Well, then, we could use him just as the war lords had done.

The 314th Bombardment Wing was alerted yesterday morning. At 2:20 p.m., pilots, bombardiers, navigators, radio men, and gunners trooped into the briefing shack to learn that the war was still on. Their target was to be apathetically small city of little obvious importance, and their commanding officer. Colonel Carl R. Storrie, of Denton, Texas, was at pains to convince them why Kumagaya, with a population of 49,000, had to be burned to the ground.

There were component parts factories of the Nakajima aircraft industry in the town, he said. Moreover, it was an important railway center.

No one wants to die in the closing moments of a war. The wing chaplain. Captain Benjamin Schmidke, of Springfield, Mo., asked the men to pray, and then the group commander jumped on the platform and cried: "This is the last mission. Make it the best we ever ran."

Colonel Storrie was to ride in one of the lead planes, dropping four 1,000-pound high explosives in the hope that the defenders of the town would take cover in buildings or underground and then be trapped by a box pattern of fire bombs to be dumped by eighty planes directly behind.

"We've got 'em on the one yard line. Let's push the ball over," the colonel exhorted his men. "This should be the final knockout blow of the war. Put your bombs on the target so that tomorrow the world will have peace."

(10) Studs Terkel interviewed John Ciardi of the USAAF about his experiences during the Second World War for his book, The Good War (1985)

When we got to Saipan, I was a gunner on a B-29. It seemed certain to me we were not going to survive. We had to fly thirty-five missions. The average life of a crew was something between six and eight missions. So you simply took the extra pay, took the badges, took relief from dirty details.

On the night before a mission, you reviewed the facts. You tried to get some sleep. The army is very good at keeping you awake forever before you have a long mission. Sleep wouldn't come to you. You get to thinking by this time tomorrow you may have burned to death. I used to have little routines for kidding myself: Forget it, you died last week. You'd get some Dutch courage out of that.

We were in the terrible business of burning out Japanese towns. That meant women and old people, children. One part of me - a surviving savage voice - says, I'm sorry we left any of them living. I wish we'd finished killing them all. Of course, as soon as rationality overcomes the first impulse, you say. Now, come on, this is the human race, let's try to be civilized.

I had to condition myself to be a killer. This was remote control. All we did was push buttons. I didn't see anybody we killed. I saw the fires we set. The first four and a half months was wasted effort. We lost all those crews for nothing. We had been trained to do precision high-altitude bombing from thirty-two thousand feet. It was all beautifully planned, except we discovered the Siberian jet stream. The winds went off all computed bomb tables. We began to get winds

at two hundred knots, and the bombs simply scattered all over Japan. We were hitting nothing and losing planes.

Curtis LeMay came in and changed the whole operation. He had been head of the Eighth Air Force and was sent over to take on the Twentieth. That's the one I was in. He changed tactics. He said. Go in at night from five thousand feet, without gunners, just a couple of rear-end observers. We'll save weight on the turrets and on ammunition. The Japanese have no fighter resistance at night. They have no radar. We'll drop fire sticks.

I have some of my strike photos at home. Tokyo looked like one leveled bed of ash. The only things standing were some stone buildings. If you looked at the photos carefully, you'd see that they were gutted. Some of the people jumped into rivers to get away from these fire storms. They were packed in so tight to get away from the fire, they suffocated. They were so close to one another, they couldn't fall over. It must have been horrible.