Spartacus Blog

In Defence of the New History in Schools

On 16th February 2024, Mike Hill, the Head of History at the Ark Soane Academy in Acton, wrote on Twitter: "Perhaps the worst development in history teaching over the last fifty years has been the idea that pupils should learn history ‘from sources' often by ‘inferring' information or piecing it together for themselves.... It's an approach that has become weirdly pervasive. In my view, it's neither a helpful way to learn about the past nor a helpful way to understand sources (or how history works). It mostly encourages guesswork and implicitly leverages wider background knowledge." (1)

As someone who was partly responsible for promoting this approach to history via my role in producing teaching materials for Tressell Publications (1980-1983) and Spartacus Educational (1984-2024) I thought it was important to answer these criticisms by setting what became known as the New History in its historical perspective.

I was the son of two unskilled factory workers. I failed my 11+ and went to a very poor secondary modern on a council estate built after the war for the people of London who had lost their homes in the Blitz. Our teachers, with no public examinations to hold over us, were more concerned with crowd control than teaching us anything. I left school at 15 without a love of history or any other subject for that matter.

I was lucky that it was while I was working in the factory that I met my first good teacher. Bob Clarke was a member of the Labour Party and an active trade unionist. Bob teaching technique was to ask me what I thought about the political issues of the time. Bob never disagreed with the answers I gave him. Instead, he asked follow-up questions that tested the logic of my original answer. (2)

Bob used the same approach to education as the Greek philosopher, Socrates. I am sure Bob had never heard of Socrates because his education had been no better than mine. Socrates pointed out that "the arguments never come out of me; they always come from the person I am talking with". He described himself as an intellectual midwife, whose questioning delivers the thoughts of others into the light of day. (3)

Past and Present Journal

To answer Bob's questions, I needed to educate myself. This included reading the Daily Herald and joining the local public library. It was during this period I developed a love of history and in 1963, at the age of 18, I read a book that was to change my life. It was E. P. Thompson's, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) For the first time I was able to read about the history of my people. Most importantly of all, Thompson's captured the voices of the men and women who were the victims of the early years of capitalism and who had tried to campaign for a democratic society. (4)

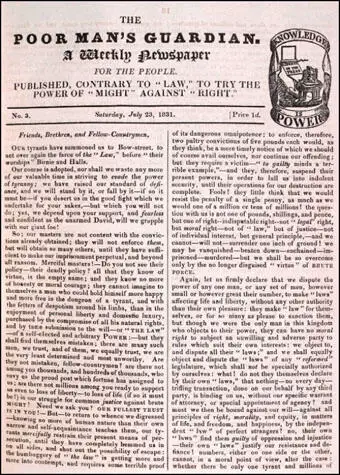

For example, Thompson writes about The Poor Man's Guardian, a newspaper that was selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week. The authorities continued to try and stop the newspaper being sold. In November 1835 Joseph Swann was sentenced to three months' imprisonment for selling the newspaper. During the trial he explained his actions. "Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament." When the Chairman of the Bench, Captain Clarke, told him to "hold his tongue", he replied: "I shall not! For I wish every man to read those publications… and whenever I come out, I'll hawk them again. And mind you (looking at Captain Clark) the first that I hawk shall be to your house." (5)

E. P. Thompson was a member of a group of left-wing historians that included Eric Hobsbawm, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, Dorothy Thompson, George Rudé, John Saville, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb who had formed the Communist Party Historians' Group. (6) Francis Beckett pointed out that these "were historians of a new type - socialists to whom history was not so much the doings of kings, queens and prime ministers, as those of the people." (7)

In 1952 members of the Communist Party Historians' Group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (8)

History Workshop Movement

In 1967 saw the arrival of the History Workshop Movement. It emerged from Ruskin College, where Raphael Samuel, the movement's initiator and presiding spirit, taught history for many decades. Other important figures included Anna Davin, Alun Howkins and Sally Alexander. The workshops that were held every year attracted up to a thousand participants. While the themes explored varied widely, the events were primarily a showcase for history seen from a non-elite perspective, "people's history" as it was labelled. In the early years this meant primarily working-class history but over time it expanded to include women's history, for which the History Workshops were the primary seedbed. (9)

Keith Flett has argued that the History Workshop was an attempt to actively recover the history of ordinary people and their movements. "In many ways this was a step forward from the sometimes rather rigid orthodoxies of more mechanical Marxist histories. It fed in directly, too, to the resurgence of socialist ideas after 1968 and to the birth of the women's movement in which the History Workshop Conference of November 1968 played a central organising role. (10)

Carol Adams, an early supporter of the History Workshop movement, saw the possibilities of this approach to classroom teaching: “In terms of the history curriculum then, change can be introduced in two ways: by ‘chipping away' at the accepted view of history - both its facts and its evidence, and through the introduction of new materials. Hopefully more educational publishers will start to respond to the implications of this. Examination boards must be pressurized to include questions about women in examination papers and to acknowledge their existence in a far wider context than at present. No responsible teacher in the upper school is going to launch into extensive work about women if there is no chance of it being examined.” (11)

The Open University

In the late 1960s, as a member of the Labour Party, I began to campaign for the formation of the Open University. Based on the educational ideas of Michael Young, the idea was to create a university for people who had failed their 11+ and did not have "A" level qualifications. At the time this was a controversial idea but Prime Minister Harold Wilson and the Minister of State for Education Jennie Lee, resisted those, including those from within the party, who argued that the students without "A" levels would not be able to deal with the rigors of a university education. (12)

The first students, including myself, enrolled in the Open University in January 1971. Arthur Marwick was the first professor of history at the OU and was a strong supporter of using primary sources in the teaching units he produced for the students. The previous year he had published The Nature of History (1970) where he analyzed at length different types of historical evidence and explored the different varieties of primary sources. (13)

At the OU as well as history I also studied psychology and education. One of my set books was Jerome Bruner's The Process of Education (1960). Bruner emphasized the importance of mastery of the structure of the subject matter. "To understand something as a specific instance of a more general case – which is what understanding a more fundamental principle or structure means – is to have learned not only a specific thing but also a model for understanding other things like it that one may encounter." (14) As he said in a later book, "knowing how something is put together is worth a thousand facts about it." (15)

Robert Phillips, in his brilliant book, History Teaching, Nationhood and the State: A Study in Educational Politics (1998), points out: "The application of Brunerian theory to history teaching was vital in the way that it placed emphasis upon method, process and skills. Pupils should therefore be introduced to the methodology of history and be made aware of history as a discipline and unique features, processes and structures." (16)

History Teaching: 1865-1975

After obtaining my degree from the OU in 1977 I took my PGCE at Sussex University with the idea of becoming a history teacher. During my studies I became aware that The Newsom Report, Half Our Future (1963), found that "history was the second most unpopular subject in the curriculum - after music." (17)

I also came across an article by Mary Price that was based on research evidence generated by the Schools Council in 1966. This showed that many pupils questioned the relevance of the subject and regarded it as "useless and boring", causing a situation whereby "history could lose the battle not only for its place in the curriculum but for a place in the hearts and minds of the young." Price argued there were three main reasons for this crisis in history teaching: (i) The history syllabuses had not changed since the turn of the century and had remained "obstinately a survey of British history"; (ii) There was a "deplorable" belief that history was only suited to more able pupils. (iii) History teaching relied far too heavily upon note taking and rote learning. (18)

I also decided to do some research into the history of the subject being taught in schools. It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that the British government took an interest in the school curriculum. The control of the elementary school curriculum was exercised principally through a system of grants. A report published in 1865 suggested that the government wanted to "discourage" the teaching of history to the "higher branches of elementary instruction". (19)

At an early stage there was opposition to the idea of pupils using primary sources in history lessons. H. E. Bourne warned that "the pupils should not be allowed to entertain the flattering notion that they are doing what historians have been obliged to do, except as the infant toddles in the path run by the athlete." (20)

Inspector reports of this period suggest that history teaching was primarily concerned with the memorization of facts and dates. However, by the early 20th Century, attitudes began to change, and it was suggested that teachers should have more power over their teaching. In 1905 the Board of Education, produced a handbook of suggestions for teachers that said: "each teacher shall think for himself, and work out for himself such methods of teaching as may use his powers to the best advantage and be best suited to the particular needs and conditions of the school." (21)

A few years later the Board of Education advised its teachers that "in the long run success or failure in History teaching, more perhaps than in any other subject, depends upon the ability and interest of the individual teacher." (22) In 1929 it said: "The history syllabus, even for schools in similar circumstances, may properly vary according to the capacity and interests of the teacher… Each teacher should think out and frame his own scheme, having regard to the circumstances of his own school, its rural or urban environment, its staffing and classification, and in some measure also to the books and the topics which most appeal to him." (23)

It seems that for most of the 20th century did not fear the power of the teacher to encourage their pupils to question the status quo. This was especially true regarding teaching about the British Empire. In 1940, in addressing the Historical Association (HA), C. M. MacInnes, who taught at Bristol University, assured his audience that the historical record showed "that we are better fitted than Nazi Germany or than other totalitarian state to govern backward races and to help them along the difficult paths of civilization." (24)

In 1946, Cicely Veronica Wedgwood, who attempted to provide a clear, entertaining middle ground between popular and scholarly works, attacked those who had ignored the dangers posed by fascism and imperialism in the 1930s: "The greater number of historical writers failed entirely to understand what was expected of them. They turned their faces away from their audience and towards their subject, turned deliberately from the present to the past… They are no more concerned with the ultimate outcome of their studies than is the research scientist with the use of poison gas in warfare. The final results arise not from the nature of the material but from the depravity of human beings; and historical research of the truly scholastic kind is not connected with human beings at all. It is pure study, like higher mathematics." (25)

A study of history teaching in grammar schools in the early 1950s discovered that the study of 20th century was rare. It pointed out that some three-quarters were following a history course which comprised: 11-12: Pre-history, ancient civilisations, or medieval history; 12-13: The Tudors and Stuarts; 13-14: The eighteenth century in England, with some American and Empire history and sometimes the eighteenth century in Europe; 14-16: Nineteenth-century English and European history (occasionally American) to be taken for the certificate examination. (26)

In public schools, history teaching was valued as a storehouse of experience for those who would lead and govern the nation, and the study of political and constitutional history was particularly valuable for this task. As Henry Scudamore-Stanhope, 9th Earl of Chesterfield, said to his son, that "An intimate knowledge of history, my dear boy, is absolutely necessary for the legislator, the orator and the statesman." (27)

Rob Gilbert has shown how English history, as taught in schools, has been explained as a success story which has been to the mutual benefit of all its citizens. Gilbert has claimed that history has been employed "to explain the process by which individual agents and social change have addressed and largely solved the problems of equality, opportunity, mobility and material welfare". (28)

Richard Aldrich and Dennis Dean, who carried out an investigation into history teaching argued: "Two conclusions therefore may be drawn at this point. The first is that over a period of 100 years from the 1860s central government was the major power in deciding how much history should be taught in schools, both at the elementary and at the secondary levels. The second is that the nature of that history was determined by the aims and objectives of certain groups – governments, examination boards, historians, teachers – which differed not only according to the interests of such groups, but also according to political, economic and educational circumstances." (29)

Aldrich and Dean suggested that things began to change at university level in the 1960s. Three issues which achieved particular prominence were those of race, gender and class. John Kenyon, pointed out that hitherto history had been written by males, and largely about that political world from which women of all classes and males of the working classes had been almost entirely excluded. However, even in the revised edition published in 1993, the important historian, Eileen Power, only merited one sentence, a quote about a male historian. (30)

The History Workshop Movement, established in 1969 at Ruskin College, attempted to promote what was now known as the "New History". According to Aldrich and Dean: "Some of these new historians were to be found in institutions of higher education. There were new universities, as at Sussex, York and Lancaster. The most radical development, the Open University, produced both a new approach to students and a new approach to historical study." (31)

A new journal, Teaching History, was launched in May 1969. It received praise from the history community and one reviewer thanked it for "sticking firmly to its original aim of showing what was going on in the best kind of history lessons" and for seeking "a remedy for the unpopularity of traditional school history in the age of comprehensive education". (32)

Chris Culpin has argued that a pamphlets published in 1971 by John Fines and Jeanette B. Coltham, entitled Educational Objectives for the Study of History played an important role in the development of history teaching. "What John Fines and Jeanette Coltham did was to suggest that ‘the study of history' was an active process, in which children could engage, and which has educational benefits for all of them, even if they never do any history as adults. Just as children learn about science and what a scientific approach to physical phenomena is by active science lessons, which we call practicals, so children learn about history and a historical approach to human existence by active history lessons." (33)

History Textbooks

Therefore, armed with my OU degree and my PGCE from Sussex University I obtained my first teaching post at Heathfield Comprehensive School in September 1978. The history textbooks the department used were very different from the materials that I had experienced at the History Workshop sessions and at the OU. The students were using Charles Peter Hill, British Economic and Social History (1977) for ‘O' level and Richard J Cootes, Britain Since 1700 (1970) for CSE. Both books employed the narrative approach with no reference to primary sources. Martin Booth has argued convincingly that these textbooks helped to develop the "inherited consensus" which prevailed in post-war history classrooms. (34)

The authors of Learning to Teach History in the Secondary School: A Companion to School Experience (2022) have argued that "The rationale for school history was based on the idea that the transmission of a positive story about the national past would inculcate in young people a sense of loyalty to the state and a reassuring and positive sense of identity and belonging." (35)

Richard Aldrich and Dennis Dean have described the history curriculum in England until the 1970s as "cast in a broadly self-congratulatory and heroic, high-political mould." (36) Or in the words of Eric Hobsbawm: "Why do all regimes make their young study some history in school? Not to understand society and how it changes, but to approve of it, to be proud of it, to be or become good citizens." (37)

Charles Peter Hill's book did not even use illustrations to break up the text. In the late 1970s textbook publishers seemed to be saying that if you needed illustrations to help you with your reading you were not up to ‘O' standard. According to one writer: "A book which has no illustrations at all seems to acknowledge that the possessor has reached the highest point of maturity and intellectual development... A person who can consume information or follow a story without the aid of pictures is demonstrating that he or she is a competent adult." (38)

Schools Council History

The department did have some materials that used primary sources. These had been produced by the Schools Council Project History 13-16. It was set up in 1972 to undertake a radical re-think of the purpose and nature of school history. It sought to revitalize history teaching in schools and to halt the erosion of history's position in the secondary curriculum. As the authors of Learning to Teach History in the Secondary School: A Companion to School Experience (2022) have pointed out the SCHP "promoted new teaching methods in order to generate more active learning among pupils and placed greater emphasis on the use of resources in the classroom… ‘The New History', as it came to be known, focused on concepts such as evidence, empathy and cause, and used primary sources as evidence in a more pupil-centred approach." (39)

We used the What is History? materials at the beginning of Year 8. This included an investigation into the death of Mark Pullen: "In this unit pupils were asked to use clues to work out what happened to a student called Mark Pullen. The objective was for the pupils to reach conclusions based on evidence in a similar way to an historian." The students loved this exercise until at the end they discovered that it was not based on a true case. (40)

I therefore decided to produce my own materials that used the same approach as the Mark Pullen case that we used in the "What is History?" course. I decided to look at the strange case of the Mary Celeste, a merchant brigantine that was discovered adrift and deserted in the Atlantic Ocean off the Azorean islands on 4th December 1872. The ship was found in a seaworthy condition under partial sail and with her lifeboat missing. The last entry in her log was dated ten days earlier. She had left New York City for Genoa on 7 th November and was still amply provisioned when found. Her cargo of alcohol was intact, and the captain's and crew's personal belongings were undisturbed. None of those who had been on board were ever seen or heard from again. I produced a booklet that told the main facts of the case in the form of primary sources. They were given secondary sources where the writer had attempted to explain why the captain and his crew had deserted the seaworthy condition. The students had to select what they believed was the theory that best explained the evidence that was available to them. (41)

The department also had single copies of SCHP's Elizabethan England 1558-1603, Britain 1815-1851, and The American West, 1840-1890 that had been published by Holmes McDougall in 1977. Although I liked the approach of these materials, I felt the primary sources were too difficult for the students aged 11-14 who would have to use them. (42) In fact, at the time, the SCHP course was initially being used by a small minority of schools. Robert Phillips has suggested that the SCHP "represented a radical attempt at reforming secondary school history, perhaps too radical for the majority of teachers." (43)

Interpretations of the Past

As a teacher I wanted to tackle something that was very important to people involved in the History Workshop Movement. That is to introduce the students to the concept of how the past is interpreted by historians. One of the pioneers of the New History, Christopher Hill pointed out that we constantly have to review the way we teach about the past: "History has to be rewritten in every generation, because although the past does not change the present does; each generation asks new questions of the past, and finds new areas of sympathy as it re-lives different aspects of the experiences of its predecessors." (44)

The historian, E. H. Carr, illustrates this point in his book, What is History? (1961): "The facts are really not at all like fish on the fishmonger's slab. They are like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use – these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts he wants. History means interpretation." (45)

Lewis Namier had suggested several years earlier that it was extremely difficult to write objective history: "One would expect people to remember the past and imagine the future. But in fact, when discoursing or writing about history, they imagine it in terms of their own experience, and when trying to gauge the future they cite supposed analogies from the past; till, by a double process of repetition, they imagine the past and remember the future." (46)

Historians have always been aware of this problem. As the British economic historian, William H. B. Court has admitted: "History free of all values cannot be written. Indeed, it is a concept almost impossible to understand, for men will scarcely take the trouble to inquire laboriously into something which they set no value upon". (47)

Ludmilla Jordanova has explained in detail why the historian has difficulty writing objective history. "No empirical activity is possible without a theory… All historians have ideas already in their minds when they study primary materials – models of human behaviour, established chronologies, assumptions about responsibility, notions of identity and so on. Of course, some are convinced that they are simply gathering facts, looking at sources with a totally open mind and only recording what is there, yet they are simply wrong to believe this." (48)

For those committed to the idea of New History it was not about producing "objective" teaching materials for the classroom. It was an attempt to show that there are different interpretations of the past and to suggest otherwise was to encourage our students to believe a falsehood. That is of course what traditional history textbooks had been doing for centuries.

However, as Arthur Chapman has pointed out, dealing with this in the classroom is a difficult process: "Understanding historical interpretation is vital to the study of the discipline of history and crucial to a wider understanding of contemporary historical culture and memory practices. Students need to come to understand the range of purposes and stances that interpretations of the past can express and practical, contextual and methodological reasons for variation in historical interpretation… We need to help students build understandings of interpretation that will enable them to explain variation rationally and appraise variant interpretation critically." (49)

Family History

My school taught the First World War in Year 9, and I thought this might be the right subject to look at interpretations of the past via primary and secondary sources. I also wanted to tackle something that was very important to people involved in the History Workshop Movement. I wanted to introduce the students to the concept of how the past is interpreted by historians.

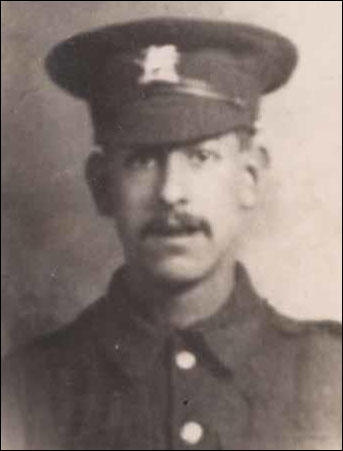

I first became interested in the war when I found in my home a bronze plaque with the words "He Died for Freedom and Honour". My father told me it was given to his mother after the death of her husband, John Edward Simkin. It appears that my grandfather was involved in tunneling under the German frontline on 29th August, 1915, when a mine exploded. He was killed with two other men. He was buried alive, and his body has never been recovered. He left no written documents and so it was impossible to discover anything about his thoughts on any subject. The family only has the photograph of him in his army uniform and the bronze plaque that became known as the "Dead Man's Penny". (50)

It was a mystery why my grandfather volunteered for the British Army in 1915. He had a reasonable job, an "envelope cutter" at the De La Rue & Company. He was 32 years-old with three young children and was under no pressure to join the army (younger men were given white feathers by young women if not in uniform). As a young child I was fascinated by this bronze plaque with my name on it. You could argue that it was the first time I became interested in history. As a child I was proud of my grandfather for giving his life to defend the British Empire. However, as I got older, and I read and wrote a great deal about the conflict, I changed my mind and considered him someone who should have been more politically aware of what was really going on.

I concluded that it would be a good idea to create some teaching materials that explained what the soldiers in the trenches felt about the war. Although my grandfather had not recorded his thoughts on the subject, I soon discovered that many others did. I called the booklet Contemporary Accounts of the First World War and started with the quotation from Aldous Huxley: "The most shocking fact about war is that its victims and its instruments are individual human beings, and that these individual beings are condemned by the monstrous conventions of politics to murder or be murdered in quarrels not their own." (51)

The booklet had sections entitled: The Outbreak of War, Trench Life, Conscription, Desertion, Shellshock, Peace Groups, the Home Front, Decision Making, Officers and Men, Disillusionment, and the Case Study: The Battle of the Somme. My main objective was to capture the voices of working-class men and women alongside those of the politicians and generals. Whereas the traditional history textbook tends to give the impression that there is an agreed account of the past, I wanted to show that the interpretation of these events can be very different depending on factors such as the role you have played or your political beliefs. I am reminded of the African epigram: "Until the lion has a historian of his own, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter." (52)

Tressell Publications

While I was doing my PGCE my personal tutor, Stephen J. Ball, persuaded me to embark on a PhD entitled, "The Role of the School in the Development of Political Consciousness". In 1979 Stephen told me that Colin Lacey, Professor of Education at Sussex University, wanted to hold a meeting with all the PhD and MA students in the education department. Colin gave a talk where he explained that he had a desire to set up a cooperative but did not know what it would produce. Thinking of the booklets I had produced I suggested we formed a cooperative that published educational materials for the classroom. Colin liked the idea and invited all those interested in this venture to a second meeting.

In 1980 ten teachers and university lecturers paid £100 to become members of Tressell Publications (named after Robert Tressell, the author of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, our favourite book) publishing cooperative. We met every Monday evening at my house and our early discussions provided us with some important guiding principles. The group decided that hopefully that the materials would help to encourage; the development of students' analytical and critical faculties; group work to improve pupils' verbal skills and decision-making; the fostering of creative and divergent thinking and the development of skills that enable young people to deal more adequately with the changes that are taking place in society. (53)

The Schools Council was set up in 1964 "to keep under review curriculum and "examinations", but at the same time not to infringe "the actual as well as inalienable right of teachers to teach what they like, how and when". This was to be ensured by allowing teachers the freedom to choose whether they used Schools Council materials, and by ensuring a teacher majority on all its committees. However, in reality classroom teachers were often sidelined in curriculum development. As Michael Young pointed out: "Up till 1973, 91 out of the 125 projects were located in universities, and only three in schools, which would seem to indicate an unquestioned assumption that curriculum development for schools is best located outside them (in universities), - this institutionalizing the separation of theory from practice." (54)

At Tressell we believed we could produce materials that could address the needs of the classroom teacher. In 1981 we published four booklets, including The Mysterious Case of The Mary Celeste and Contemporary Accounts of the First World War. Colin Lacey and I wrote an article about the venture for the Times Educational Supplement. "A great deal of classroom material is produced by teachers. These materials are often lively, tackle important problems and relate closely to the needs of pupils. Unfortunately, they are often only used by one teacher or one school. So, teachers are involved in large amounts of preparation to produce results which few others can use or criticize. Commercial publishers on the other hand frequently produce materials shaped to maximize sales." (55) This article and another one in The Guardian resulted in us being inundated with orders. Unknown to us there were a lot of teachers in the classroom looking for materials that contained accessible primary sources. (56)

Jessica Saraga, in her review of Contemporary Accounts of the First World War questioned the use of such powerful primary sources in the classroom. "The extracts combine to produce a picture almost too real – too harrowing and haunting to be dismissed; the faint, echoing plea in the anonymous young soldier's letter, ‘Don't forget me…. Don't forget me… don't forget me…'; the soldier dying in ‘no man's land', hand stuffed into his mouth to prevent his moaning drawing more comrades to their deaths to rescue him; the despairing thousands, running out of nerve, who deserted or turned their weapons on themselves. ‘What does the term patriotism mean?', interjects the text. You have to wonder whether it's right to introduce our youth to these wellsprings of human anguish, though the youngest soldiers who died were themselves only 14 or 15. This is not the material to be used lightly, or seized upon to fill a few lessons without due thought." (57)

Jessica Saraga was right to highlight the political aspects of the booklet. I selected primary sources that would illustrate the reality of warfare. I also included speeches by Christabel Pankhurst and poems by Rudyard Kipling, urging young men to join the British Army. What history textbooks did my grandfather, who enlisted in 1915, and was killed in 1916, read when he was a schoolboy? Born in 1883 he no doubt leant about the great victories that enabled the establishment of the British Empire. It is highly unlikely to be told in too much detail about what it was like to be a front-line soldier. He was therefore much more likely to believe the politicians and newspapers that suggested that the First World War would be all over in a few months, just time enough to visit a foreign country and win a few medals.

Carol Adams, a pioneer in the production of women's history teaching materials, realized the radical implications of these booklets and was much more than what went on in the classroom: "Their aim is to encourage active learning and to create genuine participation in classwork. Beyond this guiding principle they believe that pupils should be helped to develop the analytical and critical faculties required to collate and assess evidence and make their own decisions. They feel that these essential abilities need to be developed and practiced so that pupils can improve the quality of the decisions that they make." (58)

One day I received a phone call from John Slater, HMI staff inspector of history. He said he had discovered our booklets during inspections and asked if he could come and talk to us. I suggested he attended one of our Monday's meetings. He brought with him his deputy Roger Hennessy. They welcomed what we were doing and promised to publicize our materials at meetings.

John Slater was highly critical of the way history was taught in most schools. In an article he wrote after he retired, he said that until the introduction of the New History too much emphasis had been placed on "recalling accepted facts about famous dead Englishmen, and communicated in a very eccentric literary form, the examination-length essay." He went onto say that history "not only helps us to understand the identity of our communities, cultures, nations, by knowing something of the past, but also enables our loyalties to them to be moderated by informed and responsible scepticism… Historical thinking is primarily mind-opening, not socializing."

Slater described the Schools History Project as "the most significant and beneficent influence on the learning of history to emerge this century" arguing that this form of school history could give young people "not just knowledge, but the tools to reflect on, critically to evaluate, and to apply that knowledge. It proclaims the crucial distinction between knowing the past and thinking historically." (59)

SHP made it clear why history teaching needed reform: "As history educators we need to make our subject meaningful for all children and young people by relating history to their lives in the 21st century. The Project strives for a history curriculum which encourages children and young people to become curious, to develop their own opinions and values based on a respect for evidence, and to build a deeper understanding of the present by engaging with and questioning the past." (60)

John Fines was another who welcomed the approach of the SCHP: "One thing is very clear, at least: if we are to encourage imagination in every aspect of historical learning there will have to be a great deal of thinking, talking and discussing about what is happening, in process terms, and not just talk about the materials, the evidences themselves. One of the great lessons of the evaluation of the Schools' Council Project History 13-16 has been that asking pupils to think and talk and debate about what they are up to when they are doing History is one of the key factors in developing historical learning." (61)

New History and the New Right

During the meeting with the members of the Tressell publishing cooperative John Slater made it clear that with the New History we were involved in a political fight with right-wing politicians. Slater had been appointed to his post in 1968 under a Labour government. He had also had a range of different education ministers including Margaret Thatcher (1970-1974), Reginald Prentice (1974-1975), Fred Mulley (1975-1976), Shirley Williams (1976-1979), who he thought was the best minister he worked under, and Mark Carlisle (1979-1981).

The right-wing pressure group, Centre for Policy Studies, published no less than seventeen pamphlets on education, five dealing exclusively or predominantly with history. The introduction of one of its publications on history teaching, History, Capitalism & Freedom (1979) was written by Margaret Thatcher. John Slater argued that these pamphlets set the "pace and agenda" for the debate over the history curriculum in the 1980s. (62)

Alan Beattie was especially hostile to the New History and believed it subverted respect for British culture. He argued the teacher' stranglehold on history had to be broken: "He (the history teacher) has no more authority to decide the weight to be given to different but equally respectable aspects than have parents or politicians. To the extent that what is taught as history has been changed in pursuit of ‘wider social ends', and to the extent that ideological preferences have shaped the character of the history curriculum, then to that extent have teachers exceeding their authority." (63)

Margaret Thatcher appointed her right-wing political mentor, Keith Joseph, as minister of education in September 1981. Joseph announced a plan to levy tuition fees (rejected by most of Thatcher's cabinet) but he did manage to abolish the minimum grant for students. He also slashed by half university research funding. At the 1981 Conservative Party Conference, Joseph argued for a return to traditional classroom teaching styles: "I welcome the fact that the mixed-ability tide seems to have ebbed. Mixed-ability teaching calls for very rare teaching skills if it is to benefit every child in a non-selected class." (64)

Joseph was also highly critical of teacher training institutions who he believed were too progressive: He told Clyde Chitty: "You don't understand what an inert, sluggish, perverse mass there is in education. The teacher unions were... perverse, perverse; except for one or two of them, they didn't concern themselves with quality, or didn't appear to. I had union leaders make half-hour speeches without mentioning children. It was a producer lobby, not a consumer lobby." (65)

Keith Joseph was the leading representative of the "New Right". As one educationalist pointed out: "New Right ideology consisted of ‘enterprise and heritage', as well as ‘choice and control', a mixture of neo-liberal market individualism and neo-conservative emphasis upon authority, discipline, hierarchy, the nation and strong government." (66)

Duncan Graham, a former history teacher, met Joseph when he was Education Secretary: "He was a monetarist and was aware that traditional teaching was cheaper and might even act as a brake on the rising cost of maintaining the state education service. He certainly was not into spending any more money and knew that modern methods and a lower pupil-teacher ratio would mean extra spending… His heart lay with Margaret Thatcher and her group who took a simplistic view of education and set the Conservatives on the path of government by prejudice." (67)

Margaret Thatcher took a keen interest in the teaching of history in schools. As Martin Kettle pointed out: "Margaret Thatcher has fought many historic battles for what she sees as Britain's future. Few of them, though, are as pregnant with meaning as her current battle for control over Britain's own history… The debate is a surrogate for a much wider debate about the cultural legacy of the Thatcher years. It is about the right to dissent and to debate not just history but a whole range of other assumptions. If the Prime Minister can change the way that we are taught history, she will have succeeded in changing the ground rules for a generation to come. It is a big prize." (68)

John Slater feared losing his job under Thatcher and encouraged Tressell Publications to continue to produce materials for the New History approach to the subject. By the spring of 1983 we were selling 2,000 booklets a month and we were receiving a steady flow of manuscripts from the teaching profession. We found that we could no longer perform our activities on a part-time, voluntary basis and so three members of the cooperative became full-time workers. (69)

GCSE History

In 1984 I was appointed as head of the history department at Dorothy Stringer Comprehensive School in Brighton. I left Tressell Publications and along with my wife I established Spartacus Educational with the objective of producing New History teaching materials in my spare time. The need for this was reinforced by the publication in 1985 of the proposed new GCSE history examination. The GCSE criteria specified that pupils should be able to recall historical knowledge but also that they should gain the ability to "evaluate and select" knowledge and "deploy" it in a coherent form. It went on to say that pupils should be encouraged to develop a "wide variety" of skills concerned with evaluating historical evidence. (70)

Ian Dawson has pointed out that this was a major change in the way that history was taught in schools: "It's hard to explain now just how new and exciting using sources in the classroom was in the 1970s…. I never saw or read a source until I was at university. Sources just didn't appear in textbooks for O level or A level in the 1960s with the exception of Punch cartoons in the book we used for 19th century history at O level - and they were for illustration, not analysis. However, the use of sources in the 70s set a pattern that has largely stayed in place." (70a)

The most contentious issue was not the use of primary sources but the teaching and assessment of empathy. The GCSE's definition of empathy as "an ability to look at events and issues from the perspective of people in the past" had its origins in a Ministry of Education's pamphlet published in 1952 which urged teachers to cultivate in pupils "a quality of sympathetic imagination… humility about one's own age and the thing to which one is accustomed, a willingness to enter a different experience." (71)

Ann Low-Beer was one of those who had severe doubts about asking teachers to teach and assess empathy. She argued this was particularly demanding given that empathy was concerned with the affective rather than cognitive domains. (72) Martin Booth responded by suggesting that empathy could be encouraged through effective questioning, reconstructive techniques such as role play and the use of historical fiction, as well as the full range and variety of historical evidence. (73)

In January 1986, Spartacus Educational published 10 booklets in the series entitled Modern World History: Evidence and Empathy: Titles included The Russian Revolution, The Bolshevik Government, The Rise of Hitler, Hitler's Germany, America in the Twenties, Roosevelt and the New Deal, American Domestic Policy 1945-80, American Foreign Policy 1945-80, Africa Since 1945 and The Arab-Israeli Conflict.

Each unit contained a wide range of source materials and several questions that would help students to develop the ability to interpret and evaluate information. At the end of each booklet was a series of exercises that encouraged the student to look at events and issues from the perspective of people in the past. The questions in the booklets were based on the specimen papers supplied by the GCSE exam boards. There was also a teachers' handbook that went with the series which provided background information on the sources that appeared in the booklets.

As Jessica Saraga pointed out: "Most school students these days are used to evidence work too, though it's always been hard for teenagers to make a great deal of the more formal ways adults have of expressing themselves. John Simkin has thus taken ease of understanding as his first priority in selecting sources, preferring letters, autobiography and popular history, to political speeches and memoirs. It's to be hoped that the GCSE boards will do the same." (74)

The GCSE courses began in September 1986. It was not long before all the major educational publishers began producing history textbooks to accompany the course. The New History had now entered the mainstream. According to Robert Phillips, this upset what he called the New Right and its main representative, Roger Scruton, wrote a series of articles about the threat posed by this new approach to history teaching. Scruton also attacked multi-culturalism and anti-racism and the progressive ideology which under-pinned it for undermining the promotion of the idea of a ‘common' culture through education. (75)

New Right activists became intensely interested in two areas of the curriculum in particular: History and English. Ken Jones explained why the New Right concentrated on these two subjects "English and history were strongpoints of opposition, where radical ideas were deeply embedded…. History in schools, with its relativistic methods and increasing bias towards the social and the economic reflected the work of Marxist and radical historians in creating what one critic called ‘a shop steward syllabus' of modern history." (76)

Some history teachers considered the new history GCSE syllabus as too radical. Chris McGovern and Anthony Freeman, who taught history at Lewes Priory School in East Sussex, decided to enter their pupils privately for the "more traditional" Scottish Ordinary Certificate because of their profound reservations on the GCSE course. Professor Robert Skidelsky, whose children, attended the school, supported McGovern and Freeman, and wrote an article in The Independent newspaper where he accused history teachers of becoming involved in "social engineering and accused those who had designed the GCSE history course as being obsessed with the cultivation of skills rather than the teaching of historical content. He went on to call for an immediate review of the GCSE and for academics to become involved in the debate. (77)

Chris McGovern, who refused to attend my INSET courses on GCSE history and the use of computer simulations in the classroom, that I did for East Sussex history teachers, went on to become advisor to the Policy Unit at 10 Downing Street and the Chairman of the Campaign for Real Education. The group opposes the teaching of sociology and politics and has been critical of anti-racism and anti-sexism campaigns. (78)

History National Curriculum

In January 1987, Kenneth Baker, Secretary of State for Education, announced the intention of the government to introduce a national core curriculum. Baker argued that England had adopted an "eccentric" approach which had left the school curriculum to "individual schools and teachers" which contrasted with the centralized system in Europe. Pointing to the weaknesses and apparent failure of the English system, he indicated that greater central control was necessary. (79) Supporters of the New History became concerned when Baker wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph where he announced his support for Chris McGovern's criticism of GCSE history and that empathy was "a thing of the past". (80)

Baker established a History Working Group (HWG) to advise him on the introduction of National Curriculum History. Baker appointed only two teachers to the HWG: Carol White was a secondary school teacher who had met Baker at a Conservative Party function and had been critical of aspects of SHP. Robert Guyver was a primary school teacher who was committed to the teaching of "discrete" history to young pupils. Two teacher trainers: Anne Low-Beer, who had already raised serious doubts about the teaching of history (see Note 61) and Gareth Elwyn Jones who had previously argued for a fusion of "traditional" and "new" history. Two academics: John M. Roberts and Alice Prochaska, and three members with LEA backgrounds. Commander Michael Saunders-Watson, was appointed as Chairman of the HWG. He was the President of the Historic Houses Association and the owner of Rockingham Castle. Saunder-Watson later admitted his appointment followed Baker staying at his castle. As Robert Phillips pointed out: "Such criteria for selection to the body that was to shape the teaching was hardly going to fill history teachers with confidence." (81)

However, as Duncan Graham later pointed out: "Saunders Watson's only obvious credentials were that he ran a stately home which was used by many schools and as a result had a keen interest in history and education. He appeared to everybody to be a peculiarly Tory choice and looked to many as the first overt political appointment. Everybody feared the worst and characterized him as a right-wing amateur who would follow the party line. He went on to be a great but welcome surprise to history teachers." (82)

Martin Roberts, the headteacher of Cherwell School, and a member of the Historical Association Council, wrote: "Imagine for a moment (in an unfashionably empathetic way) that you are a member of the history working group. You have been chosen to identify history courses which will improve on best practice and win and sustain the confidence of teachers, parents, governors and Parliament. However, you have been selected by a government famous for its ideological conviction and for its distaste for much of the contemporary professional practice at a time when teachers themselves seem both acutely sensitive about their professional autonomy yet fiercely argumentative about the best way forward for their professional autonomy yet fiercely argumentative about the best way forward for their subject in schools. And of all the major subjects of the National Curriculum history is the one most easily influenced by political values. You only have a year to prepare the report while keeping up with your normal job. Can you imagine a more thankless task? (83)

Supporters of the New History methodology had reason to be confident that their views would be expressed at HWG meetings. Alice Prochaska, the author of History of the General Federation of Trade Unions (1982) was sympathetic to recent developments in history teaching and was a member of the history workshop movement. In an article she later wrote that she was surprised that Baker had appointed her to the HWG. (84)

Roger Hennessy, HMI staff inspector of history, was appointed as an advisor of the HWG. It was the same man who had visited my home with John Slater in 1982, to encourage us at Tressell Publications to continue with our work in producing materials for the New History. Other good news was the announcement in the summer of 1989 that two history teachers, Tim Lomas and Chris Culpin, had been co-opted onto the HWG. They were both known to be supporters of the SHP. (85)

The first meeting of the HWG took place on 24 January 1989. The group was told that it would have to produce interim recommendations by 30th June 1989 and then provide the Secretary of State with final advice by Christmas 1989. Newspapers began speculating about what would be in the HWG interim report. The Daily Telegraph claimed that it supported methods which neglected fact and that it advocated empathy and historical imagination. The Observer reported that although the HWG would request that children learn historical skills, it also suggested that the group had steered a "middle line" between "traditionalists" and "progressives". (86)

The HWG Interim Report was published on 10 August 1989. The report acknowledged that there was "growing public concern" about the perceived preponderance of skills-based courses at GCSE at the expense of British history but emphasized that the HWG did not "wish to take sides in these debates which seem to some extent contrived". It pointed out that the main objective was to design "a broad, balanced and coherent course of history for pupils from the age of 5 to 16; a course which will combine rigour, intellectual excitement, and planned programming, and one which respects knowledge and skills equally." (87)

John MacGregor, who had replaced Kenneth Baker as Secretary of State for Education in July 1989, wrote to the HWG to consider three issues when compiling the Final Report. Firstly, he asked the group to pay more attention to chronology. Secondly, he asked for more British history at KS3 and KS4. Thirdly, MacGregor doubted whether the recommendations put "sufficient emphasis on the importance of acquiring historical knowledge and on ensuring that knowledge can be assessed." (88)

The right-wing press supported what MacGregor had said in the letter. The Daily Telegraph reported that MacGregor had "sided himself firmly with traditionalists" and had largely rejected the Interim Report. (89) The Daily Mail said: "Get the facts straight, history men are told." (90) The Daily Express added that MacGregor had told the HWG that "Children must know dates, events and characters, and not get bogged down with too much theorizing about the nature of history." (91) Only The Guardian stood up for the HWG and warned that MacGregor's intervention "has an ominous smack about it, rather as if we were soon to return to the solid, drum banging certainties of H. E. Marshall's Our Island Story." (92)

Margaret Thatcher was also highly critical of the Interim Report: "I was appalled. It put the emphasis on interpretation and enquiry as against content and knowledge. There was insufficient weight given to British history. There was not enough emphasis on history as chronological study. Ken Baker wanted to give the report a general welcome while urging its Chairman to make the attainment targets specify more clearly factual knowledge and increasing the British history content. But this in my view did not go far enough. I considered the document comprehensively flawed and told Ken that there must be major, not just minor, changes." (93)

The History Working Group received over a thousand responses to the Interim Report, mainly from teachers and historians but also from various New Right groups. One of the main opponents of the HWG report was from Stuart Deuchar, a member of the Campaign for Real Education and a Centre for Policy Studies pamphleteer. Deuchar, educated at Repton and Cambridge University, was a farmer but had taught history in a private school for two years. In his pamphlet, The New History: A Critique (1989) he expressed his bitter opposition to the progressive methodology and the conceptional frameworks represented by the SHP. He denounced those teachers who believed that the teaching of British history had the potential to be "nationalistic" and this approach had caused "the loss of a huge slice of our national heritage". (94)

The Final Report of the HWG was published on 3rd April 1990. It was little different from the Interim Report and had not changed it in response to the criticisms made by New Right groups and the Conservative Party supporting press. The report defended itself against the attacks on the New History: "In order to know about, or understand, an historical event we need to acquire historical information but the constituents of that information – the names, dates, and places – provide only starting points for understanding. Without understanding, history is reduced to parrot learning and assessment to a parlour memory game." (95) The report pointed out the overall objective of the HWG had been to "give equal weight to knowledge, understanding and skills." (96)

In Chapter 10 the HWG dealt with the controversial subject of empathy. It outlined the ways in which field trips, museum visits, drama, role play and other simulation techniques could "convey the image of living in the past"; they could provide the opportunity to "explore, and come to imagine aspects of history"; they could show the "differences between living in the past and living in the present" and could provide the opportunity to "explore, and come to imagine aspects of history"; these could even be the "source of good, imaginative writing, and they help to bring history to life". However, these exercises had to be based on primary sources and rooted in "an uncompromising respect for evidence". (97)

Chris Culpin explained that teachers had been encouraging the development of "empathy" in young people for some time: "We do teach young people that the attitudes, values and beliefs of people in the past are important in helping us understand them, that people have motives for their actions and that these can be complex and varied, including value systems that are not the same as ours. I don't see how you can study history properly without addressing these perspectives, and these insights are part of our historical enquiry." (98)

Duncan Graham pointed out: "Following the interim report, various interest groups began to battle over the reforms, and it looked as if history would end in failure. In the final report the working group stood by the fundamental findings of the interim report which caused such concern to ministers. There were many good, detailed refinements and, in an attempt to satisfy ministers, almost too many facts were included in the programmes of study, but when it came to the basic principle nothing had been altered, indeed little could be altered as the working group's conclusions were unarguable." (99)

Members of the History Working Group suspected that the Final Report to be criticized by the government. It stated with regard to future revisions of the proposals, the HWG warned that they be "undertaken in such a way as to avoid what appears to be public suspicion that school history may be manipulated for political purposes." (100)

Conservatives were disappointed with the failure of Commander Michael Saunders-Watson, Chairman of the HWG, to produce a more "traditionalist" report. He later explained his time on the HWG: "I had my eyes opened by the HWG. I had lived with history and had been taught the subject in a very old-fashioned way. Then when I heard the arguments put forward by HWG members it came as something of a culture shock. I became impressed with many of the arguments which I never knew existed. I learnt that history is not just about facts, but it is also about acquiring information, processes and learning. History involves a combination of content, understanding and information." (101)

Margaret Thatcher refused to accept defeat and wrote in her memoirs: "It (the Final Report) did not put greater emphasis on British history. But the attainment targets it set out did not specifically include knowledge of historical facts, which seemed to me extraordinary. However, the coverage of some subjects – for example twentieth century history – was too skewed to social, religious, cultural and aesthetic matters rather than political events… I raised these points with John (MacGregor) on the afternoon of Monday 19 March. He defended the report's proposals. But I insisted that it would not be right to impose the sort of approach which it contained. It should go out to consultation but no guidance should be present be issued." (102)

Conservative historians such as Robert Skidelsky, Norman Stone, Jonathan Clark, Lord Max Beloff and Lord Robert Blake, formed the History Curriculum Association (HCA) to "defend the integrity of history as a school subject". (103) All these men published articles in the press criticizing the HWG Final Report. Raphael Samuel, the founder of the History Workshop movement, was one of the most significant supporters of the HWG report. (104)

Robert Skidelsky was aware that Raphael Samuel and the History Workshop Movement was at the heart of these proposals. Skidelsky attacked Samuel in The Independent for his over-zealous advocacy of the need to teach "history from below" (particularly the history of gender) as opposed to "history from above" (such as Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar). (105)

The following week Samuel replied to Skidelsky. He reminded him that Trafalgar was followed a year later by the most crushing of Napoleon's victories at Austerlitz and by the subsequent collapse of the Third Coalition. As Samuel pointed out "were it not for the heroic circumstances of Nelson's death and perhaps the nineteenth century romanticization of war, it is possible that we would know no more of it than we do the Battle of Copenhagen or the battle of Tenerife." On the other hand, the Married Women's Property Act of 1882 (which Skidelsky had taken particular issue over) was "a landmark in the history of women's rights" yet hardly received a mention either in university or school history courses. (106)

Importantly, senior figures in the History Association, decided to endorse the findings of the HWG on the grounds that there was sufficient potential that the Secretary of State would reject the HWG's advice and replace the Final Report with something much worse. Martin Roberts, Chair of the HA schools' sub-committee, declared that the Final Report was "a considerable achievement" and was to be the "foundation on which durable school history courses are able to be built." (107)

Over 300 history teachers attended the SHP Conference in April 1990. Organizers of the Conference ensured that key elements of the Final Report were copied and distributed to delegates. Crucially, three former members of the HWG attended the Conference to explain the philosophy and thinking behind the report. The Conference welcomed many aspects of the Final Report. However, delegates expressed concerns about prescription, content overload, assessment, and the over-emphasis upon British history. (108)

Margaret Thatcher eventually accepted defeat and blamed Kenneth Baker for supporters of the New History winning the battle over the National Curriculum. She admitted in her autobiography: "By now I had become thoroughly exasperated with the way in which the national curriculum proposals were being diverted from their original purpose… There was no need for the national curriculum proposals and the testing which accompanied them to have developed as they did. Ken Baker paid too much attention to the DES, the HMI and progressive educational theorists in his appointments and early decisions; and once the bureaucratic momentum had begun it was difficult to stop." (109)

The government established the National Curriculum Council (NCC) in 1990 to offer the Secretary of State advice on the basis of statutory consultation with teachers and other professional groups. Dr Nicholas Tate was appointed professional officer for history and was to play an important figure in shaping history in the National Curriculum. Tate invited me to a meeting soon after he took up the role and found him sympathetic to the objectives of the "New History". He had been an advocate of GCSE and had written a student support book entitled, Countdown to GCSE History (1986). (110)

History Task Group

The NCC established the History Task Group (HTG) to provide non-statutory guidance for supporting teachers' implementation of the History National Curriculum. The first meeting of the HTG meeting was held on 22nd February 1990. Unlike the HWG, the HTG was comprised exclusively of professionals actively involved in education. Meetings were attended by representatives of the HMI and the Schools Examination and Assessment Council (SEAC). Eventually, the HTG proposed three attainment targets: (i) Knowledge & Understanding ( Causation, Change and Similarity/Difference); (ii) Interpretations of History; (iii) The Use of Historical Sources. It was stated that there should be two profile components for history, one for attainment target 1 and the other for attainment targets 2 and 3, equally weighted. The effect was to confirm the impression that "Knowledge and Understanding" were given priority in the proposals. (111)

The History Task Group Consultation Report was published in December 1990. The right-wing press mistakenly described it as a victory for the traditionalists, ignoring the gains made by the supporters of the New History. The Times declared: "The knowledge of facts will be the basis for history lessons" as it was "twice the value of each of the other two targets". (112) The Daily Mail claimed that "Ministers win the battle for history." (113) Only The Daily Telegraph realized that the NCC had not succumbed to traditionalists. It argued that although the proposals ostensibly elevated the learning of knowledge, "it upholds the original working group's view that pupils should not be assessed on specific items of historical knowledge". (114)

Kenneth Clarke, the new Secretary of State for Education, was not happy with the Consultation Report. He did not like the idea of students looking at primary sources and developing different interpretations of the past. He knew he could not remove attainment targets 2 and 3 but could undermine its political impact. He announced that history would no longer be compulsory at KS4. (115)

This infuriated the Historical Association (HA) and Martin Roberts, Chair of its schools' sub-committee, wrote that: "It is only in the last two compulsory years of state schooling that young people have the maturity to understand the complexity of the modern world. Without this essential historical knowledge of twentieth-century developments, how else could they understand the recent changes in East Europe or the crisis in the Middle East or Britain's role in Europe and the world? (116)

Clarke, according to The Financial Times, had a natural distrust of teachers. (117) This helps to explain why he announced that he was unhappy about any school students studying 20 th century history. "I have made certain further changes… I believe that is right to draw some distinction between the study of history and the study of current affairs." (118) Duncan Graham, chairman and chief executive of the National Curriculum Council, commented: "Clarke it appeared, was quite convinced that teachers could not be trusted to teach modern history in an even-handed way." (119)

This time he did not have the support of right-wing historians who believed the study of 20th century history, especially the two world wars, would help to encourage the development of the right type of values in young people. Robert Skidelsky regretted that history syllabuses would not refer to some of the most important changes that have shaped the modern world. (120) Lord Robert Blake, who had argued strongly against the History Working Group proposals called Clarke's decision "ridiculous". (121)

Those on the left also disagreed with Clarke about teaching about the history of the 20th Century. Jack Straw of the Labour Party accused Clarke of attempting to interfere in a political way in the history curriculum. (122) Martin Roberts described Clarke's decision as “incomprehensible” and claimed that the events of the late 1960s through to the 1980s were not current affairs but were crucial for understanding the present: “The Gulf Crisis, the Common Market, changes in the Welfare State and the coming general election all depend on a good understanding of the recent past for people to make sense of them.” (123) Chris Culpin pointed out that history teachers often “study history backwards: start with a fairly recent event, and see how history explains it.” (124)

One of the most important attacks on Kenneth Clarke came from John Slater, the former chief HMI for history. Slater argued it was vital for teachers to deal with issues such as the Gulf War, not because pupils did not have enough information but because they were exposed to too much of it through the media. It is the responsibility of history teachers to help their students reflect on and use their knowledge and experience, “through analysis and critical evaluation”. Slater suggests that at the heart of history is “informed skepticism, of responsible doubt, hostile to the stereotypes and bamboozlers… Is this what lies at the heart of Mr Clarke's anxiety that warns historians off the events of the past 30 years?” (125)

In the House of Commons, Clarke pointed out that the study of current affairs was not being banned, merely that they were not included in the Statutory Orders. (126) After discussion with his right-wing critics Clarke initially decided to impose a 1945 cut-off for the history curriculum. Talks with DES officials convinced him to agree on a rolling review date which was subsequently decided as twenty years. (127) However, Clarke said "my view remains that pupils should not be legally required to study contemporary events… because of the difficulty of treating such matters with historical perspective." (128)

Martin Roberts described the changes as an improvement but still regarded the twenty-year rule as ridiculous: "Mr Clarke accepts that history should be taught to help pupils understand how the world in which we live has been shaped by events in the twentieth century. But how can they make sense of, say, the Middle East if their studies end before the Yom Kippur War?" (129)

Roberts told The Independent newspaper that Clarke had insulted the professionalism of teachers for "there is no logical reason to impose the 1970 ceiling on study. The decision shows that Mr Clarke does not believe we teach in a balanced way. It demonstrates a complete misunderstanding of teachers and teaching. Most of the history teachers I know are sensitive not to express their own opinions in class." (130)

A former member of the History Working Group, Henry Hobhouse, was disappointed by the changes that had been made to the History Curriculum Final Report. He claimed that it was now "bland, innocuous, an evident political compromise; it inevitably lacks cohesion, consistent quality, bite, flavour and authority." (131)

Kenneth Clarke had definitely undermined some of the original proposals. This was especially true of the decision that history would no longer be compulsory at KS4. However, supporters of the New History were pleased with the survival of attainment targets 2 and 3: Interpretations of History and The Use of Historical Sources. Spartacus Educational and other publishers had the freedom to produce teaching materials that were more in line with those pioneered by the Schools Council Project History 13-16.

New Right Rebellion

Traditionalists refused to accept defeat and continued to publish pamphlets attacking the New History now being taught in schools. An important figure in this was Sheila Lawlor, a research fellow at Sidney Sussex College, who wrote a series of pamphlets for the Centre of Policy Studies on school history teaching between 1988-1995. (She became Baroness Lawlor as part of Boris Johnson's 2022 Special Honours List). In an interview in The Times newspaper Lawlor argued against the New History approach as it would result in pupils being "confused by being given different versions (of the past) and might be better off to master the facts". (132)

The Conservative government helped their campaign by appointing "traditionalists" to bodies overseeing the National Curriculum. In July 1991, Philip Halsey, Chairman and Chief Executive of Schools Examination and Assessment Council (SEAC) and Duncan Graham, Chairman of the National Curriculum Council (NCC), were replaced by Brian Griffiths and David Pascall. Griffiths (later Baron Griffiths of Fforestfach) was Margaret Thatcher's chief policy adviser. He remained Director of the Number 10 Policy Unit and was also Chairman of the Centre of Policy Studies (1991 to 2001). Pascal had also been one of Thatcher's policy advisers (1983-1984).

The following year John Marks was appointed to the NCC. Marks was a veteran of the New Right. Marks was also one of the founders of the Hillgate Group, which in December 1986 issued a pamphlet, The Reform of British Education, calling for the removal of state schools from local authority control and the reintroduction of selective education. John Marenbon, the husband of Sheila Lawlor, joined SEAC. Robert Skidelsky, Chris McGovern and Anthony Freeman, the founders of the Campaign for Real Education, that was set up in 1987 to oppose the new history GCSE syllabus, were also appointed to the history committee of SEAC. (133)

Some members of SEAC began to apply pressure on John Patten, who had replaced Kenneth Clarke as Secretary of State for Education in April 1992. Baron Griffiths, Chief Executive of SEAC, wrote to Patten to demand a review of school history, as Griffiths believed that "children should be tested on facts and dates rather than on theoretical skills." Robert Skidelsky shared Griffiths' discontent and described the assessment and testing arrangements as "half-baked". (134)

On 7th April 1992 John Patten wrote to Sir Ron Dearing, the Chairman of the School Curriculum & Assessment Authority (SCAA), which was about to replace SEAC and NCC, to conduct a complete review of the National Curriculum. (135) Given the difficulties and pressures, particularly in relation to content overload and assessment, faced by teachers in the previous few years, the Dearing Review was warmly welcomed by the teaching profession. Robert Skidelsky demanded that the Dearing Report should simply recommend that schools "test knowledge". (136) Stuart Deuchar, a member of the Campaign for Real Education and a Centre of Policy Studies pamphleteer, argued "the case against the assessment of historical knowledge has collapsed". (137) Some supporters of the New History commented that it was a mistake to think that "the battle is won", for the Dearing Review provided a "door to a right-wing, and much more unacceptable history curriculum". (138)

The National Curriculum and its Assessment: Final Report was published in December 1993. It recommended the establishment of a series of review groups, under the authority of SCAA, to offer proposals for reform, specifically to recommend how the programs of study of each subject could be simplified and made less prescriptive and to suggest ways in which the number of attainment targets and statements of attainment could be reduced. (139)

The Times Educational Supplement suggested that history was "likely to be the most hotly debated" of the review groups because although it comprised mainly history teachers and advisers, who were "progressives", the group also included GCSE rebel Chris McGovern and right-wing philosopher Anthony O'Hear, who were described as "traditionalists". The article predicted the rows would be about "facts versus skills" and "quarrels about the centrality of British history" would re-emerge. (140)

Although outnumbered on the SCAA History Review Group, McGovern and O'Hear did not provide a united front. (141) McGovern was angered by the fact that there was to be only 36 per cent "uniquely British" history in the revised proposals and had expressed this anger in a five-page letter to Ron Dearing. He was appalled that "well-known" events in British history such as the Great Fire of London and the Gunpowder Plot had been left out of the proposals. O'Hear supported the SCAA proposals and argued in the Daily Mail "can it really be pretended that the Plague and the Fire are key political events, on a level with the Civil War, the Interregnum and the Restoration." (142)

McGovern became so dissatisfied with the review group he published his own "Minority Report" through the Campaign for Real Education. McGovern claimed that SCAA officers dominated the group and were only interested in slimming the National Curriculum than with providing a rationale for the new proposals. He argued that it was disgraceful that the History Review Group had omitting "great figures" such as Nelson, Florence Nightingale, Queen Victoria, and Winston Churchill and the "great landmarks" such as Agincourt, the War of the Roses, the Napoleonic Wars and the development of British democracy since 1900. (143)

McGovern released his Minority Report the day before the SCAA Review of National Curriculum History was published. Most of the newspapers ran stories based almost entirely upon McGovern's report. The Daily Express announced that the proposals would allow "trendy" staff to "teach social history instead of great events." (144) The Sun declared that "Britain's glorious past banished from lessons. Thus OUT go Henry VIII, Churchill, Guy Fawkes and Nelson but IN comes struggles of Namibian women." (145) The Daily Telegraph published large sections of McGovern's report in its newspaper. (146)

This was a great distortion of the SCAA Review of National Curriculum History. It was reported that professional officers at SCAA actually considered taking legal action against McGovern. It was pointed out that it was absurd to claim that "every" British King and Queen was left out. Similarly, other "great figures" and "key events" such as Nelson and Churchill and the French and American Revolutions were specifically mentioned in other parts of the proposals. (147)

John Patten, Secretary of State for Education, also attacked McGovern's report and said it was "bunkum and balderdash to suggest that British history is not going to be taught property, that we are going to see the death of British history." He added that the "proposals show that almost all children will be taught about key figures such as Queen Victoria, the Tudor monarchs, Florence Nightingale, King Alfred, Sir Francis Drake, Nelson and Wellington." (148)