Spartacus Blog

Why the decline in newspaper readership is good for democracy

Monday, 9th April, 2018

According to the latest figures newspapers are currently losing sales at a rate of more than ten per cent year on year. In 1956 the Daily Mirror, was the highest selling newspaper, with average of 4,649,696 copies a day. In 2018, its sells 583,192. The newspaper with the largest circulation today, The Sun, sells 1,545,594 copies. In 1987, when it claimed that it was the newspaper that won the 1987 General Election for the Conservative Party because of its campaign against Neil Kinnock, sold 3,993,000 copies. The circulation of the serious newspapers have seen an even more dramatic decline. The Daily Telegraph sold 1,439,000 in 1980, now its circulation is 385,346.

In a major study carried out five years ago, discovered that 84% of the UK population claimed to have read a printed daily newspaper in the past year. "Those aged 18 to 24 years old were found to be the least likely to have read a newspaper (71%) in the past year, compared with 90% of people aged over 55... Those aged 18 to 24 were found to be most likely to have read a newspaper online, with 61% having read one in the last 12 months. This compares to just 39% of those aged 55 or over having read a newspaper website in the last year... The research seems to confirm industry fears that those most in the habit of buying newspapers can be directly correlated with age, suggesting that newspapers will die with the older generation." (1)

Latest figures suggest the majority of young people never read a newspaper. Initially it was thought that this decline would give greater power to television companies to control the information we receive. In 1960 the Pilkington Committee on Broadcasting concluded that "until there is unmistakable proof to the contrary, the presumption must be that television is and will be a main factor in influencing the values and moral standards of our society."

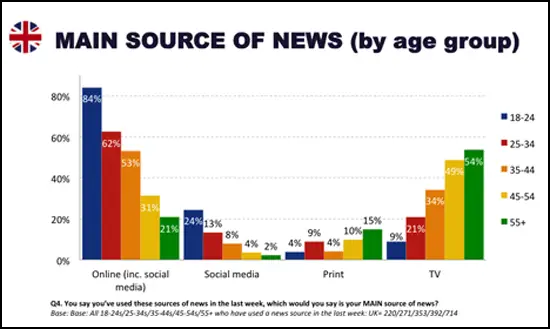

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in 2016, social media has overtaken television as young people's main source of news. Of the 18-to-24-year-olds surveyed, 28% cited social media as their main news source, compared with 24% for TV. The report says that this survey has "profound consequences both for publishers and the future of news production". (2)

Oxford University Media Report (30th May, 2017)

The move from traditional sources of news like television and printed newspapers is particularly clear if we look at differences between age groups. There are very clear generational divides. Asked to identify their main source of news, online comes out number one in every age group under 45 - and for those under 25, social media are by now more popular than television. (3)

To understand why this is good for democracy we need to understand the history of newspapers. Britain's first newspapers appeared during the English Civil War (they were called newssheets or newsbooks). In 1643 the Royalists began publishing Mercurius Aulicus and Parliament responded by producing Mercurius Brittanicus. They of course were no more than propaganda sheets recording the atrocities being carried out by the opposition. They were extremely popular taking over from the drama and entertainment left by the closure of the theatres. (4)

Some members of the New Model Army began complaining they were fighting for the rights of Parliament when they themselves did not have the vote. This included Lieutenant-Colonel John Lilburne, who became the leader of the group called the Levellers. They published newspapers and pamphlets demanding voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (5)

Oliver Cromwell was willing to let the Levellers have their say while the war was going on but took a different approach when victory was achieved. On 28th October, 1647, members of the New Model Army began to discuss their grievances at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin. This became known as the Putney Debates. Leaders of the Leveller movement, including John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and John Wildman, were arrested and their pamphlets were burnt in public. (6)

Over the next two hundred years the government attempted to keep control over the publication of newspapers. One of the first things that King Charles II did when the monarchy returned to power in 1660 was to pass legislation "For Restraining the Printing of New Books and Pamphlets of News without leave". The first newspaper to be given permission to be published was the Daily Courant in 1702. It is often claimed that this was beginning of the "freedom of the press". In fact, in was the start of a long struggle for the right to publish information available to the people of this country. (7)

One method of restricting sales of newspapers to the masses was to impose taxes on paper, newspapers and pamphlets. This was first introduced in 1712. If the stamp duty checked newspaper circulation, the libel laws provided the main curb on their contents. Any publication was a seditious libel if it tended to bring into hatred or contempt the King, the Government, or the constitution of the United Kingdom. As W. H. Wickwar, the author of The Struggles for the Freedom of the Press, 1819-1832 (1928) pointed out: "It was thus criminal to point out any defects in the Constitution or any errors on the part of the Government, if disaffection might thereby be caused." (8)

The main political issue at the time was the vote. John Wilkes, was one of the few members of the upper-classes who believed in an increase in the number of people could vote in elections. To help him in his campaign he established his own newspaper, The North Briton. On 23rd April 1763, George III and his ministers decided to prosecute Wilkes for seditious libel. He fled to France but returned to stand in the 1768 election. There were just a couple of constituencies that were not under the control of any one person. This was true of the Middlesex constituency. (9)

After being elected Wilkes was arrested and taken to King's Bench Prison. For the next two weeks a large crowd assembled at St. George's Field, a large open space by the prison. On 10th May, 1768 a crowd of around 15,000 arrived outside the prison. The crowd chanted "Wilkes and Liberty", "No Liberty, No King", and "Damn the King! Damn the Government! Damn the Justices!". Fearing that the crowd would attempt to rescue Wilkes, the troops opened fire killing seven people. Anger at these events led to disturbances all over London. (10)

On 8th June 1768 Wilkes was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 22 months imprisonment and fined £1,000. Wilkes was also expelled from the House of Commons but in February, March and April, 1769, he was three times re-elected for Middlesex, but on all three occasions the decision was overturned by Parliament. (11)

The Times was founded in 1785 and began life as a government-subsidised newspaper. Its founder, John Walter, received £300 a year from the Treasury. In 1788 Walter attempted to produce a newspaper that appealed to a larger audience. This included stories of the latest scandals and gossip about famous people in London. One of these stories about the Prince of Wales resulted in Walter being fined £50 and sentenced to two years in Newgate Prison. (12)

Producing newspapers was a dangerous business and so most radicals concentrated on publishing pamphlets commenting on the political situation. In 1791 Tom Paine, the son of a Quaker corset maker, and a former excise officer from Lewes, published his most influential work, The Rights of Man. In the book Paine attacked hereditary government and argued for equal political rights. Paine suggested that all men over twenty-one in Britain should be given the vote and this would result in a House of Commons willing to pass laws favourable to the majority. "The whole system of representation is now, in this country, only a convenient handle for despotism, they need not complain, for they are as well represented as a numerous class of hard-working mechanics, who pay for the support of royalty when they can scarcely stop their children's mouths with bread." (13)

The book also recommended progressive taxation, family allowances, old age pensions, maternity grants and the abolition of the House of Lords. Paine also argued that a reformed Parliament would reduce the possibility of going to war. "Whatever is the cause of taxes to a Nation becomes also the means of revenue to a Government. Every war terminates with an addition of taxes, and consequently with an addition of revenue; and in any event of war, in the manner they are now commenced and concluded, the power and interest of Governments are increased. War, therefore, from its productiveness, as it easily furnishes the pretence of necessity for taxes and appointments to places and offices, becomes a principal part of the system of old Governments; and to establish any mode to abolish war, however advantageous it might be to Nations, would be to take from such Government the most lucrative of its branches. The frivolous matters upon which war is made show the disposition and avidity of Governments to uphold the system of war, and betray the motives upon which they act." (14)

The British government was outraged by Paine's book and it was immediately banned. Paine was charged with seditious libel but he escaped to France before he could be arrested. Paine announced that he did not wish to make a profit from The Rights of Man and anyone had the right to reprint his book. It was printed in cheap editions so that it could achieve a working class readership. Although the book was banned, during the next two years over 200,000 people in Britain managed to buy a copy. By the time he had died, it is estimated that over 1,500,000 copies of the book had been sold in Europe. (15)

Mary Wollstonecraft had been converted to Unitaranism by Richard Price. She read Paine's book and in response published Vindication of the Rights of Women. In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." (16)

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. One critic described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing. (17)

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. One critic described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing. After the publication of these pamphlets both Paine and Woollstonecraft were forced to live in France. (18)

Thomas Spence, a former schoolmaster from Newcastle, moved to London and attempted to make a living by selling the works of Paine on street corners. He was arrested but soon after he was released from prison he opened a shop in Chancery Lane where he sold radical books and pamphlets. In 1793 Spence started a newspaper, Pigs' Meat. He said in the first edition: "Awake! Arise! Arm yourselves with truth, justice, reason. Lay siege to corruption. Claim as your inalienable right, universal suffrage and annual parliaments. And whenever you have the gratification to choose a representative, let him be from among the lower orders of men, and he will know how to sympathize with you." (19)

In 1802 William Cobbett started his newspaper, the Political Register. At first he supported the Tories but he gradually became more radical. By 1806 he was a strong advocate of parliamentary reform. He was not afraid to criticise the government in and in 1809 he was tried and convicted for sedition and sentenced to two years' imprisonment in Newgate Prison. When Cobbett was released he continued his campaign against newspaper taxes and government attempts to prevent free speech. (20)

Another newspaper publisher, George Holyoake, later wrote: "The governing classes were terrified of the apparition of the wilful little printing press... A free press was never a terror to the people - it was their hope. It was the governing classes who were under alarm." He claimed that during the reign of George III (1760-1820): "Every editor editor being assumed to be a criminally disposed person and naturally inclined to blasphemy and sedition had to enter into sureties. Every person possessing a printing-press or types for printing and every type-founder was ordered to give notice to the Clark of the Peace." (21)

The first progressive newspaper for the upper-classes was The Examiner. Founded in 1808 it carried the inscription below its title-piece: "Paper and print 3½d., Taxes on Knowledge 3½d., price 7d." Edited by Leigh Hunt, gave support to radicals in Parliament such as Henry Brougham and Sir Francis Burdett and the political ideas of people like Robert Owen and Jeremy Bentham. As well as advocating social reform, the magazine published the poetry of young writers such as Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Hazlitt. In 1812 Leigh Hunt was arrested and charged with libel after publishing an article criticizing the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. He was found guilty and sentenced to two years' imprisonment and a £500 fine. (22)

Five major political reformers, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Richard Carlile, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and Mary Fildes were invited to speak at a public meeting at at St. Peter's Field in Manchester on 16th August, 1819. Several of the newspaper reporters, including John Tyas (The Times), Edward Baines (Leeds Mercury), John Smith (Liverpool Mercury) and John Saxton (Manchester Observer) joined the speakers on the hustings. The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field by midday. (23)

At 1.30 p.m. the magistrates came to the conclusion that "the town was in great danger". William Hulton therefore decided to instruct Joseph Nadin, Deputy Constable of Manchester, to arrest the speakers on the platform. When Captain Hugh Birley and his men reached the hustings they not only arrested the speakers but the newspaper reporters on the hustings. John Edward Taylor reported: "A comparatively undisciplined body, led on by officers who had never had any experience in military affairs, and probably all under the influence both of personal fear and considerable political feeling of hostility, could not be expected to act either with coolness or discrimination; and accordingly, men, women, and children, constables, and Reformers, were equally exposed to their attacks." (24)

Samuel Bamford was in the crowd and later described the attack on the crowd: "The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads... On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled... A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises. In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again." (25)

By 2.00 p.m. the soldiers had cleared most of the crowd from St. Peter's Field. In the process, 18 people were killed and about 500, including 100 women, were wounded. (23) Some historians have argued that Lord Liverpool, the prime minister, and Lord Sidmouth, his home secretary, were behind the Peterloo Massacre. However, Donald Read, the author of Peterloo: The Massacre and its Background (1958) disagrees with this interpretation: "Peterloo, as the evidence of the Home Office shows, was never desired or precipitated by the Liverpool Ministry as a bloody repressive gesture for keeping down the lower orders. If the Manchester magistrates had followed the spirit of Home Office policy there would never have been a massacre." (26)

E. P. Thompson disagrees with Read's analysis. He has looked at all the evidence available and concludes: "My opinion is (a) that the Manchester authorities certainly intended to employ force, (b) that Sidmouth knew - and assented to - their intention to arrest Hunt in the midst of the assembly and to disperse the crowd, but that he was unprepared for the violence with which this was effected." (27)

Richard Carlile managed to avoid being arrested and after being hidden by local radicals, he took the first mail coach to London. The following day placards for Sherwin's Political Register began appearing in London with the words: 'Horrid Massacres at Manchester'. A full report of the meeting appeared in the next edition of the newspaper. The authorities responded by raiding Carlile's shop in Fleet Street and confiscating his complete stock of newspapers and pamphlets. (28)

Moderate reformers in Manchester were appalled by the decisions of the magistrates and the behaviour of the soldiers. Several of them wrote accounts of what they had witnessed. Archibald Prentice sent his report to several London newspapers. When John Edward Taylor discovered that John Tyas of The Times, had been arrested and imprisoned, he feared that this was an attempt by the government to suppress news of the event. Taylor therefore sent his report to Thomas Barnes, the editor of The Times. The article that was highly critical of the magistrates and the yeomanry was published two days later. (29)

Tyas was released from prison. The Times mounted a campaign against the action of the magistrates at St. Peter's Field. In one editorial the newspaper told its readers "a hundred of the King's unarmed subjects have been sabred by a body of cavalry in the streets of a town of which most of them were inhabitants, and in the presence of those Magistrates whose sworn duty it is to protect and preserve the life of the meanest Englishmen." As these comments came from an establishment newspaper, the authorities found this criticism particularly damaging.

Other journalists at the meeting were not treated as well as Tyas. Richard Carlile wrote an article on the Peterloo Massacre in the next edition of The Republican. Carlile not only described how the military had charged the crowd but also criticised the government for its role in the incident. Under the seditious libel laws, it was offence to publish material that might encourage people to hate the government. The authorities also disapproved of Carlile publishing books by Tom Paine, including Age of Reason, a book that was extremely critical of the Church of England. In October 1819, Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and was sentenced to three years in Dorchester Gaol. (30)

Carlile was also fined £1,500 and when he refused to pay, his Fleet Street offices were raided and his stock was confiscated. Carlile was determined not to be silenced. While he was in prison he continued to write material for The Republican, which was now being published by his wife. Due to the publicity created by Carlile's trial, the circulation of The Republican increased dramatically and was now outselling pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (31)

The government was greatly concerned by the dangers of the parliamentary reform movement and welcomed the action taken by the Manchester magistrates at St. Peter's Field. The Prince of Wales, the future King George IV, sent a message to the magistrates thanking them "for their prompt, decisive, and efficient measures for the preservation of the public peace". (32)

Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary, sent a letter of congratulations to the Manchester magistrates for the action they had taken. He also sent a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action. This was supported by John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, the Lord Chancellor, who was of the clear opinion" that the meeting "was an overt act of treason". (33)

As Terry Eagleton has pointed out the "liberal state is neutral between capitalism and its critics until the critics look like they're winning." (34) When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (35)

(i) Training Prevention Act: A measure which made any person attending a gathering for the purpose of training or drilling liable to arrest. People found guilty of this offence could be transported for seven years.

(ii) Seizure of Arms Act: A measure that gave power to local magistrates to search any property or person for arms.

(iii) Seditious Meetings Prevention Act: A measure which prohibited the holding of public meetings of more than fifty people without the consent of a sheriff or magistrate.

(iv) The Misdemeanours Act: A measure that attempted to reduce the delay in the administration of justice.

(v) The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious.

(vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty.

Francis Place, one of the leaders of the reform movement, wrote that "I despair of being able adequately to express correct ideas of the singular baseness, the detestable infamy, of their equally mean and murderous conduct. They who passed the Gagging Acts in 1817 and the Six Acts in 1819 were such miscreants, they could they have acted thus in a well-ordered community they would all have been hanged." (36)

These measures were opposed by the Whigs as being a suppression of popular rights and liberties. They warned that it was unreasonable to pass national laws to deal with problems that only existed in certain areas. The Whigs also warned that these measures would encourage radicals to become even more rebellious. Earl Grey, the leader of the Whigs in the House of Commons, kept a low profile over the issue as he was "anxious to preserve the pre-eminence of the landed class... as many in his party profited from an undemocratic system of representation". (37)

The trial of the organisers of the St. Peter's Field meeting took place in York between 16th and 27th March, 1820. The men were charged with "assembling with unlawful banners at an unlawful meeting for the purpose of exciting discontent". Henry Orator Hunt was found guilty and was sent to Ilchester Gaol for two years and six months. Joseph Johnson, Samuel Bamford and Joseph Healey were each sentenced to one year in prison. (38)

John Edward Taylor was a successful businessman who was radicalized by the Peterloo Massacre. Taylor felt that the newspapers did not accurately record the outrage that the people felt about what happened at St. Peter's Fields. Taylor's political friends agreed and it was decided to form their own newspaper. Eleven men, all involved in the textile industry, raised £1,050 for the venture. It was decided to call the newspaper the Manchester Guardian. A prospectus was published which explained the aims and objectives of the proposed newspaper: "It will zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty, it will warmly advocate the cause of Reform; it will endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy." (39)

The first four-page edition appeared on Saturday 5th May, 1821 and cost 7d. Of this sum, 4d was a tax imposed by the government. The Manchester Guardian, like other newspapers at the time, also had to pay a duty of 3d a lb. on paper and three shillings and sixpence on every advertisement that was included. These taxes severely restricted the number of people who could afford to buy newspapers.

Two aspects of the Six Acts was to prevent the publication of radical newspapers. The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act was a measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious. The Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act was an attempt to subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty.

One of the most popular radical newspapers was the Black Dwarf with a circulation of about 12,000. Its editor was Thomas Jonathan Wooler. This was a period of time it was possible to make a living from being a radical publisher. "The means of production of the printed page were sufficiently cheap to mean that neither capital nor advertising revenue gave much advantage; while the successful Radicalism, for the first time, a profession which could maintain its own full-time agitators." (40)

After the passing of the Six Acts Wooler was arrested and charged with "forming a seditious conspiracy to elect a representative to Parliament without lawful authority". Wooler was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. (41)

On his release from prison Wooler modified the tome of the Black Dwarf in an effort to comply with the terms of the Six Acts. As a result he lost circulation of those like Richard Carlile, the editor of The Republican, who refused to reduce his radicalism. This was a successful strategy and he was able to outsell pro-government newspapers such as The Times. (42)

To survive, Wooler had to rely on financial help from Major John Cartwright. However, on Cartwright's death on 23rd September 1824, he was forced to close the newspaper down. He wrote in the final edition that there was no longer a "public devotedly attached to the cause of parliamentary reform". Whereas in the past they had demanded reform, now they only "clamoured for bread". (43)

A Stamp Tax was first imposed on British newspapers in 1712. The tax was gradually increased until in 1815 it had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes. During this period most working people were earning less than 10 shillings a week and this therefore severely reduced the number of people who could afford to buy radical newspapers.

Campaigners against the stamp tax such as William Cobbett and Leigh Hunt described it as a "tax on knowledge". As one of these editors pointed out: "Let us then endeavour to progress in knowledge, since knowledge is demonstrably proved to be power. It is the power knowledge that checks the crimes of cabinets and courts; it is the power of knowledge that must put a stop to bloody wars." (44)

Chartists, including Henry Hetherington, James Watson, John Cleave, George Julian Harney and James O'Brien joined people like Richard Carlile in the fight against stamp duty. As these radical publishers refused to pay stamp-duty on their newspapers, this resulted in fines and periods of imprisonment. In 1835 the two leading unstamped radical newspapers, the Poor Man's Guardian, and The Cleave's Police Gazette, were selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week and the Morning Chronicle all month. It was estimated at the time that the circulation of leading six unstamped newspapers had now reached 200,000. (45)

These newspapers had no problems finding people willing to sell these newspapers. Joseph Swann sold unstamped newspapers in Macclesfield. He was arrested and in court he was asked if he had anything to say in his defence: "Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications." The judge responded by sentencing him to three months hard labour. (46)

Stamp duty and taxes on newspapers finally came to and end in 1861. Over the next forty years newspapers were fairly equally divided between the two parties. Conservative Party and the Liberal Party. The Times, The Telegraph and the Morning Post (Conservative Party) and The Daily Chronicle, The Daily News and the Manchester Guardian. However, by this stage, the price of the newspaper did cover the cost of production. Therefore newspapers relied heavily on advertising. This made it impossible for the left to produce a newspaper that could be sold at a price that could command a wide readership. To keep their support, political parties always rewarded newspaper barons with titles.

The journalist Alfred Harmsworth decided to start a newspaper based on the style of newspapers published in the USA. His younger brother, Harold Harmsworth, an accountant, arranged for the raising of the money for the venture. By the time the first issue of the Daily Mail appeared for the first time on 4th May, 1896, over 65 dummy runs had taken place, at a cost of £40,000. When published for the first time, the eight page newspaper cost only halfpenny. Slogans used to sell the newspaper included "A Penny Newspaper for One Halfpenny", "The Busy Man's Daily Newspaper" and "All the News in the Smallest Space". (47)

Harmsworth made use of the latest technology. This included mechanical typesetting on a linotype machine. He also purchased three rotary printing machines. In the first edition Harmsworth explained how he could use these machines to produce the cheapest newspaper on the market: "Our type is set by machinery, and we can produce many thousands of papers per hour cut, folded and if necessary with the pages pasted together. It is the use of these new inventions on a scale unprecedented in any English newspaper office that enables the Daily Mail to effect a saving of from 30 to 50 per cent and be sold for half the price of its contemporaries. That is the whole explanation of what would otherwise appear a mystery." (48) It was later claimed that these machines could produce 200,000 copies of the newspaper per hour. (49)

The Daily Mail was the first newspaper in Britain that catered for a new reading public that needed something simpler, shorter and more readable than those that had previously been available. One new innovation was the banner headline that went right across the page. Considerable space was given to sport and human interest stories. It was also the first newspaper to include a woman's section that dealt with issues such as fashions and cookery. Most importantly, all its news stories and articles were short. The first day it sold 397,215 copies, more than had ever been sold by any newspaper in one day before. (50)

Harmsworth gained many of his ideas from America. He had been especially impressed by Joseph Pulitzer, the owner of the New York World. He also concentrated on human-interest stories, scandal and sensational material. However, Pulitzer also promised to use the paper to expose corruption: "We will always fight for progress and reform, never tolerate injustice or corruption, always fight demagogues of all parties, always oppose privileged classes and public plunderers, never lack sympathy with the poor, always remain devoted to the public welfare, never be satisfied with merely printing news, always be drastically independent, never be afraid to attack wrong, whether by predatory plutocracy or predatory poverty." (51)

In order to do this Pulitzer pioneered the idea of investigative reporting that eventually became known as muckraking. As Harold Evans, the author of The American Century: People, Power and Politics (1998) has pointed out: "Crooks in City Hall. Opium in children's cough syrup. Rats in the meat packing factory. Cruelty to child workers... Scandal followed scandal in the early 1900s as a new breed of writers investigated the evils of laissez-faire America... The muckrakers were the heart of Progressivism, that shifting coalition of sentiment striving to make the American dream come true in the machine age. Their articles, with facts borne out by subsequent commissions, were read passionately in new national mass-circulation magazines by millions of the fast-growing aspiring white-collar middle class." (52)

Alfred Harmsworth completely rejected this approach to journalism. "Looking back, what it (the Daily Mail) lacked most noticeably was a social conscience... Alfred had no desire to start looking for social evils, and no need. What he had to keep in mind were the tastes of a new public that was becoming better educated and more prosperous, that wanted its rosebushes and tobacco and silk corsets and tasty dishes, that liked to wave a flag for the Queen and see foreigners slip on a banana skin." (53)

One of his journalists, Tom Clarke, claimed that his newspaper was for people who were not as intelligent as they thought they were: "Was one of the secrets of the Daily Mail success its play on the snobbishness of all of us? - all of us except the very rich and the very poor, to whom snobbishness is not important; for the rich have nothing to gain by it, and the poor have nothing to lose." (54)

Harmsworth made full use of the latest developments in communications. Overseas news-gathering offices opened in New York and Paris were aided by advances in cable transmission speed at the General Post Office, which had reached 600 words per minute by 1896. He also exploited the expanding British railway system to distribute the newspaper to the home market so that people all over Britain could read the newspaper over their breakfasts. It has been claimed that the Daily Mail was the first truly national newspaper. (55)

Alfred Harmsworth made it clear to the leaders of the Conservative Party that the newspaper would provide loyal support against the movement towards social change. Arthur Balfour, the leader of the party in the House of Commons, sent a private letter to Harmsworth. "Though it is impossible for me, for obvious reasons, to appear among the list of those who publish congratulatory comments in the columns of the Daily Mail perhaps you will allow me privately to express my appreciation of your new undertaking. That, if it succeeds, it will greatly conduce to the wide dissemination of sound political principles, I feel assured; and I cannot doubt, that it will succeed, knowing the skill, the energy, the resource, with which it is conducted. You have taken the lead in the newspaper enterprise, and both you and the Party are to be heartily congratulated." (56)

In July 1896, Harmsworth asked a friend, Lady Bulkley, to write to Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, the new prime minister, suggesting that in return for supporting the Conservative Party, he should be rewarded with a baronetcy. The letter pointed out that as well as owning several pro-conservative newspapers he had recently established "the Daily Mail... at a cost of near £100,000". Salisbury refused but was willing to offer a knighthood instead. Harmsworth rejected the offer and commented that he was willing to wait for a baronetcy. (57)

In April 1905, Alfred Harmsworth, established Associated Newspapers Limited with a capital of £1,600,000, the shares of which swiftly sold out. His income for the year was £115,000. Apart from his newspaper business he had other stock worth £300,000. Despite his growing wealth he was still dissatisfied and craved titles and acceptance from the ruling class. (58)

On 23rd June, it was announced that Harmsworth had received a baronetcy. The Daily Telegraph reported that it was unusual for a man "to win so much success in so limited a time". (59) Those newspapers that supported the Liberal Party were less complimentary. The Daily Chronicle stated that "Mr. Harmsworth's is the name of the most general interest in a list that is more remarkable for quantity than quality". (60) The most bitter comment came from The Daily News, "having been conspicuously passed over for several years, Sir Alfred Harmsworth has arrived at his baronetcy... for all he did during the Boer War." (61)

The Conservative press campaigned against every effort to pass legislation that favoured the majority of the population. This includes universal suffrage, old-age pensions, unemployment pay, progressive taxation, freedom to form trade unions, the National Health Service, the minimum wage, etc.

After the decline of the Liberal Party the press have overwhelmingly supported the Conservative Party. The only time that the Labour Party had anywhere near 50% of the support of the press was in the 1945 General Election, when they won a landslide victory. The Daily Mirror, The Daily Herald and The Daily Chronicle gave them a combined readership of 7,459,000. Whereas The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph, The Daily Express, The Times and The Daily Sketch had a circulation of 7,986,000. At the election Labour got 47.7% of the vote against 36.2% for the Conservatives.

This situation did not arise again until 1997 when after Tony Blair did a deal with Rupert Murdoch he gained the support of News International. According to Lance Price, Blair's director of communications, the deal involved consulting with Murdoch over party policy. As a result of the deal newspapers supporting Blair totaled 7,856,347 compared to 5,445,287 for the Conservatives. This was translated to votes of 43.2% for Labour and 30.7% for Conservatives.

At the last election the total daily readership supporting the Conservative Party was 7,145,551 compared to 685,906 for the Labour Party. Yet, unlike previous elections, this was not reflected in the votes cast: Conservatives (42.4%) and Labour (40.0%). Clearly, newspapers are losing their influence over the electorate. Especially the young who now tend to get their political news from the web.

According to the YouGov report How Britain voted at the 2017 general election: "In electoral terms, age seems to be the new dividing line in British politics. The starkest way to show this is to note that, amongst first time voters (those aged 18 and 19), Labour was forty seven percentage points ahead. Amongst those aged over 70, the Conservatives had a lead of fifty percentage points... In fact, for every 10 years older a voter is, their chance of voting Tory increases by around nine points and the chance of them voting Labour decreases by nine points. The tipping point, that is the age at which a voter is more likely to have voted Conservative than Labour, is now 47 – up from 34 at the start of the campaign." (62)

An analysis of social media behaviour during the election also reveals the decreasing influence of the press barons. The Press Gazette reported that anti-Tory news websites such as Canary, Skwakbox, Evolve and London Economic, were far more important in communicating political information than traditional newspapers: "Final figures for the most-shared stories on social media during the general election campaign show that anti-Tory articles dominated. Although satirical stories feature, there are no fake news stories in the most-shared list – suggesting this was not a factor in the election. The findings suggest that social media (mainly Facebook) acted as a counterbalance to printed newspapers."

The newspaper studied the top 100 most-shared stories during the 2017 General Election campaign. It discovered that "45 were anti-Tory/pro-Labour, 46 were neutral and five were pro-Tory. The remaining four were judged to be not relevant". The article goes on to argue that left-wing websites offering an alternative slant on the news – The Canary, Skwakbox and The London Economic – have six articles in the top 100 most-shared list. The Canary claimed more viral stories in the top 100 than the Daily Mail, Telegraph and Express. It featured four times, while they appeared just once each. The Canary’s most-shared article on the general election was headlined: NHS workers have spoken. The general election is our only chance of saving the health service. It had a total of 63,500 shares." (63)

References

(1) Arif Durrani, Campaign (13th March, 2013)

(2) Jane Wakefield, BBC News (15th June, 2016)

(3) Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Oxford University Media Report (30th May, 2017)

(4) Diane Purkiss, The English Civil War: A People's History (2007) page 207

(5) John F. Harrison, The Common People (1984) page 198

(6) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) page 216

(7) Stanley Harrison, Poor Men's Guardians (1974) page 13

(8) W. H. Wickwar, The Struggles for the Freedom of the Press, 1819-1832 (1928) pages 26-27

(9) Stanley Harrison, Poor Men's Guardians (1974) pages 15-22

(10) J. F. C. Harrison, The Common People (1984) page 253

(11) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) pages 269-270

(12) Francis Williams, Dangerous Estate: The Anatomy of Newspapers (1957) pages 62-65

(13) Tom Paine, The Rights of Man (1791) page 74

(14) Tom Paine, The Rights of Man (1791) page 169

(15) Harry Harmer, Tom Paine: The Life of a Revolutionary (2006) pages 71-72

(16) Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792)

(17) Claire Tomalin, The Life and Death of Mary Woolstonecraft (1974) pages 134-135

(18) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) pages 176-179

(19) Stanley Harrison, Poor Men's Guardians (1974) page 39

(20) George Holyoake, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892) page 27

(21) J. F. C. Harrison, The Common People (1984) page 256

(22) Nicholas Roe, Leigh Hunt : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(23) John Edward Taylor, The Times (18th August, 1819)

(24) Samuel Bamford, Passage in the Life of a Radical (1843) page 163

(25) Martin Wainwright, The Guardian (13th August, 2007)

(26) Donald Read, Peterloo: The Massacre and its Background (1958) page 120

(27) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) page 750

(28) Richard Carlile, Sherwin's Political Register (18th August, 1819)

(29) John Edward Taylor, The Times (18th August, 1819)

(30) Joel H. Wiener, Radicalism and Freethought in Nineteenth-Century Britain: The Life of Richard Carlile (1983) page 41

(31) Philip W. Martin, Richard Carlile : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(32) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) page 750

(33) Lord Sidmouth, letter to Lord Liverpool (1st October, 1819)

(34) Terry Eagleton, Why Marx was Right (2011) page 197

(35) J. F. C. Harrison, The Common People (1984) page 257

(36) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) page 727

(37) Annette Mayer, The Growth of Democracy in Britain (1999) page 36

(38) John Belchem, Henry Hunt : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(39) Geoffrey Taylor, John Edward Taylor : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(40) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) page 740

(41) James Epstein, Thomas Wooler : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(42) Philip W. Martin, Richard Carlile : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(43) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963) page 891

(44) Richard Carlile, The Republican (4th October, 1820)

(45) Stanley Harrison, Poor Men's Guardians (1974) page 94

(46) Poor Man's Guardian (12th November, 1831)

(47) S. J. Taylor, The Great Outsiders: Northcliffe, Rothermere and the Daily Mail (1996) page 32

(48) Alfred Harmsworth, Daily Mail (4th May, 1896)

(49) Kennedy Jones, Fleet Street and Downing Street (1919) page 138

(50) Francis Williams, Dangerous Estate: The Anatomy of Newspapers (1957) page 140

(51) Joseph Pulitzer, New York World (May, 1883)

(52) Harold Evans, The American Century: People, Power and Politics (1998) page 94

(53) Paul Ferris, The House of Northcliffe: The Harmsworths of Fleet Street (1971) page 20

(54) Tom Clarke, diary entry (1st January, 1912)

(55) J. Lee Thompson, Northcliffe: Press Baron in Politics 1865-1922 (2000) page 35

(56) Arthur Balfour, letter to Alfred Harmsworth (7th May, 1896)

(57) J. Lee Thompson, Northcliffe: Press Baron in Politics 1865-1922 (2000) page 337

(58) J. Lee Thompson, Northcliffe: Press Baron in Politics 1865-1922 (2000) page 120

(59) The Daily Telegraph (23rd June, 1905)

(60) The Daily Chronicle (23rd June, 1905)

(61) The Daily News (23rd June, 1905)

(62) Chris Curtis, How Britain Voted at the 2017 General Election (13th June, 2017)

(63) Freddy Mayhew, General election: Only five out of top 100 most-shared stories on social media were pro-Tory (12th June, 2017)

Previous Posts

Why the decline in newspaper readership is good for democracy (18th April, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party (12th April, 2018)

George Osborne and the British Passport (24th March, 2018)

Boris Johnson and the 1936 Berlin Olympics (22nd March, 2018)

Donald Trump and the History of Tariffs in the United States (12th March, 2018)

Karen Horney: The Founder of Modern Feminism? (1st March, 2018)

The long record of The Daily Mail printing hate stories (19th February, 2018)

John Maynard Keynes, the Daily Mail and the Treaty of Versailles (25th January, 2018)

20 year anniversary of the Spartacus Educational website (2nd September, 2017)

The Hidden History of Ruskin College (17th August, 2017)

Underground child labour in the coal mining industry did not come to an end in 1842 (2nd August, 2017)

Raymond Asquith, killed in a war declared by his father (28th June, 2017)

History shows since it was established in 1896 the Daily Mail has been wrong about virtually every political issue. (4th June, 2017)

The House of Lords needs to be replaced with a House of the People (7th May, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Caroline Norton (28th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Mary Wollstonecraft (20th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Anne Knight (23rd February, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Elizabeth Heyrick (12th January, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons: Where are the Women? (28th December, 2016)

The Death of Liberalism: Charles and George Trevelyan (19th December, 2016)

Donald Trump and the Crisis in Capitalism (18th November, 2016)

Victor Grayson and the most surprising by-election result in British history (8th October, 2016)

Left-wing pressure groups in the Labour Party (25th September, 2016)

The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism (3rd September, 2016)

Leon Trotsky and Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party (15th August, 2016)

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England (7th August, 2016)

The Media and Jeremy Corbyn (25th July, 2016)

Rupert Murdoch appoints a new prime minister (12th July, 2016)

George Orwell would have voted to leave the European Union (22nd June, 2016)

Is the European Union like the Roman Empire? (11th June, 2016)

Is it possible to be an objective history teacher? (18th May, 2016)

Women Levellers: The Campaign for Equality in the 1640s (12th May, 2016)

The Reichstag Fire was not a Nazi Conspiracy: Historians Interpreting the Past (12th April, 2016)

Why did Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst join the Conservative Party? (23rd March, 2016)

Mikhail Koltsov and Boris Efimov - Political Idealism and Survival (3rd March, 2016)

Why the name Spartacus Educational? (23rd February, 2016)

Right-wing infiltration of the BBC (1st February, 2016)

Bert Trautmann, a committed Nazi who became a British hero (13th January, 2016)

Frank Foley, a Christian worth remembering at Christmas (24th December, 2015)

How did governments react to the Jewish Migration Crisis in December, 1938? (17th December, 2015)

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)