Sarah Wedgwood

Sarah Wedgwood, the daughter of Richard Wedgwood, a prosperous merchant and the eldest brother of Thomas and John Wedgwood of Burslem, was born in 1734. Jenny Uglow claims that Sarah grew into an attractive woman. She was "not beautiful, but striking, tall and slim with pale skin, reddish hair and grey-green eyes". (1)

Sarah married her third cousin, Josiah Wedgwood, on 25th January 1764. According to his biographer, Robin Reilly: "Sarah was a substantial heiress and brought with her a considerable dowry, said to have been £4,000, which came under Wedgwood's control. It was a love match, successfully negotiated in spite of initial opposition from her father, and there is ample evidence that the marriage was a happy one. Sarah was intelligent, shrewd, and well educated - better, in fact, than her husband - and they shared a broad sense of humour and a strong sense of family duty. In the first years of their marriage, she helped Josiah with his work, learning the codes and formulae in which he recorded his experiments, keeping accounts, and giving practical advice on shapes and decoration." (2)

Josiah Wedgwood wrote that "for a handful of the first months after matrimony" he wished "to hear, see, feel or understand nothing" but his wife. He told Thomas Bentley that as a result of the damage caused by his early smallpox, his physiology was so adapted to feeling pain that sensual pleasures was more "than I shall ever be able to express." (3)

Over the next few years Sarah Wedgwood had seven children: Susannah Wedgwood (1765–1817), John Wedgwood (1766–1844), Josiah Wedgwood II (1769–1843), Thomas Wedgwood (1771–1805), Catherine Wedgwood (1774–1823), Sarah Wedgwood (1776–1856) and Mary Anne Wedgwood (1778–86).

In 1787 Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and William Dillwyn established the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Other supporters were William Allen, John Wesley, Samuel Romilly, Thomas Walker, John Cartwright, James Ramsay, Charles Middleton, Henry Thornton and William Smith. Sharp was appointed as chairman. He accepted the title but never took the chair. Clarkson commented that Sharp "always seated himself at the lowest end of the room, choosing rather to serve the glorious cause in humility... than in the character of a distinguished individual." Clarkson was appointed secretary and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Samuel Hoare reported subscriptions of £136. (4)

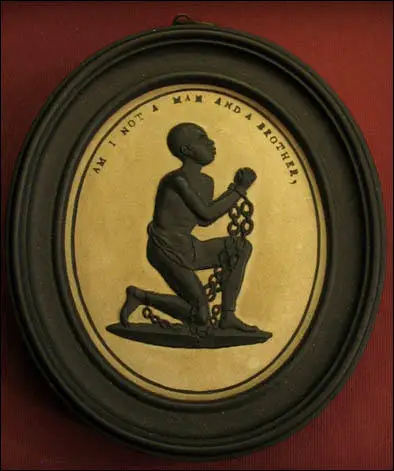

Josiah Wedgwood joined the organising committee and Sarah Wedgwood became involved in the campaign. As Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has pointed out: "Wedgwood asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands beseechingly." It included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" Hochschild goes onto argue that "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks, the image was an instant hit... Wedgwood's kneeling African, the equivalent of the label buttons we wear for electoral campaigns, was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause." (5)

Thomas Clarkson explained: "Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and this fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom." (6)

Hundreds of these images were produced. Benjamin Franklin suggested that the image was "equal to that of the best written pamphlet".Men displayed them as shirt pins and coat buttons. Whereas women used the image in bracelets, brooches and ornamental hairpins. In this way, women could show their anti-slavery opinions at a time when they were denied the vote. Later, a group of women designed their own medal, "Am I Not a Slave And A Sister?" (7)

Sarah Wedgwood died in 1815. However, her daughter, also called Sarah, continued with the family campaign against slavery. In April, 1825, she joined with Lucy Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, and Sophia Sturge to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). (8) The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions." (8)

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America". (9)

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Ann Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery. (10)

Sarah Wedgwood died in 1856.

Primary Sources

(1) Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate not Gradual Abolition (1824)

In the great question of emancipation, the interests of two parties are said to be involved, the interest of the slave and that of the planter. But it cannot for a moment be imagined that these two interests have an equal right to be consulted, without confounding all moral distinctions, all difference between real and pretended, between substantial and assumed claims. With the interest of the planters, the question of emancipation has (properly speaking) nothing to do. The right of the slave, and the interest of the planter, are distinct questions; they belong to separate departments, to different provinces of consideration. If the liberty of the slave can be secured not only without injury, but with advantage to the planter, so much the better, certainly; but still the liberation of the slave ought ever to be regarded as an independent object; and if it be deferred till the planter is sufficiently alive to his own interest to co-operate in the measure, we may for ever despair of its accomplishment. The cause of emancipation has been long and ably advocated. Reason and eloquence, persuasion and argument have been powerfully exerted; experiments have been fairly made, facts broadly stated in proof of the impolicy as well as iniquity of slavery, to little purpose; even the hope of its extinction, with the concurrence of the planter, or by any enactment of the colonial, or British legislature, is still seen in very remote perspective, so remote that the heart sickens at the cheerless prospect. All that zeal and talent could display in the way of argument, has been exerted in vain. All that an accumulated mass of indubitable evidence could effect in the way of conviction, has been brought to no effect.

It is high time, then, to resort to other measures, to ways and means more summary and effectual. Too much time has already been lost in declamation and argument, in petitions and remonstrances against British slavery. The cause of emancipation calls for something more decisive, more efficient than words. It calls upon the real friends of the poor degraded and oppressed African to bind themselves by a solemn engagement, an irrevocable vow, to participate no longer in the crime of keeping him in bondage...

The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods.

The West Indian planters have occupied much too prominent a place in the discussion of this great question....The abolitionists have shown a great deal too much politeness and accommodation towards these gentlemen.... Why petition Parliament at all, to do that for us, which... we can do more speedily and effectually for ourselves?

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)