Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson, the eldest of three children, was born in Wisbech on 28th March 1760. His father, John Clarkson (1710–1766), was the headmaster of Wisbech Grammar School. His younger brother, John Clarkson, was born on 4th April 1764. (1)

Clarkson later wrote about his father: "The duties of the grammar school engaged nearly the whole of the day and left little more than the hours of evening for these visits of mercy and he often did not return into the town till after midnight, but he allowed neither darkness, nor the coldness of the night nor the tempestuousness of the bitterest winter weather to frustrate his design... It was on one of these visits to the sick poor of his parish, that he caught a fever which deprived him of his life. The news of his death caused an universal burst of sorrow as soon as it was known in those parts."

After the death of his father, the family continued to live in the town. In 1775 Clarkson was sent to St Paul's School. The historian, Ellen Gibson Wilson, has pointed out: "The pupils paid fees and supplied their own books. Carrying their wax candles they swarmed into the high hall each day at 7 a.m. and took their seats on the benches which rose in three tiers along the walls. It was always freezing cold; no fires were allowed at any time. (2)

In 1779 Clarkson won a place at St. John's College, Cambridge. His biographer, Hugh Brogan, has argued: "He was a devout, assiduous soul, taking after his father, a notably conscientious parson. He seems to have had no sense of humour at all, though he liked others to be merry. Physically, he was tall and heavy, with a strong constitution. His brother John, by contrast, was small and lively, but was as strongly religious, and shared to the full his brother's strong human sympathy: he detested the navy's use of flogging as a punishment. Thomas Clarkson graduated BA in 1783 with a solid rather than a distinguished degree in mathematics, but remained at Cambridge to prepare himself to be a clergyman. He was decidedly ambitious; after winning a university Latin essay prize in 1784 he resolved to win it again the following year." (3)

Thomas Clarkson and the Slave-Trade

In 1785 Cambridge University held an essay competition with the title: "Is it rights to make men slaves against their will?" Clarkson had not considered the matter before but after carrying out considerable research on the subject submitted his essay. He found a book written by Anthony Benezet, entitled Some Historical Account of Guinea: An Inquiry Into the Rise and Progress of the Slave Trade, published by a recently formed Society of Friends committee. Clarkson later wrote: "In this precious book I found almost all I wanted." Clarkson won first prize and was asked to read his essay to the University Senate. (4)

On his way home to London he had a spiritual experience. He later described how he had "a direct revelation from God ordering me to devote my life to abolishing the trade." Clarkson was worried that as a young man if he had the necessary skills to "qualify him to undertake a task of such magnitude and importance". However, each time he doubted, the result was the ame: "I walked frequently into the woods, that I might think on the subject in solitude, and find relief to my mind there. But the question still recurred... surely some person should interfere." (5)

Clarkson read everything he could on the African slave trade. He obtained access to some "manuscript papers" of a friend who had been involved in the trade. He also interviewed some officers who had served in the West Indies. He realised that slavery was not "merely an abstract problem" as it existed in "British colonies which were governed by the laws of England, and that its existence was not only condoned by the British public but also actively encouraged by them." (6)

Clarkson made contact with William Dillwyn, a former assistant to Anthony Benezet, but now a merchant in Britain. At his home in Walthamstow he tutored Clarkson in the anti-slavery movements on both sides of the Atlantic. Dillwyn told Clarkson about the work of James Ramsay and Granville Sharp and the attempts by the Society of Friends to bring an end to the trade. (7)

Clarkson's close friend, Henry Crabb Robinson, commented that Clarkson became very close to the Quakers: "The gravity, great earnestness, and quakerish simplicity of his appearance.... made his presence a sort of phenomenon among great men, and men of the world. He was at home only among the Quakers." Clarkson once said of the Quakers that he shared "nine parts in ten of their way of thinking." (8)

In June 1786 Clarkson published Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. The book traced the history of slavery to its decline in Europe and arrival in Africa, made a powerful indictment of the slave system as it operated in the West Indian colonies and attacked the slave trade supporting it. William Smith argued that the book was a turning-point for the slave trade abolition movement and made the case "unanswerably, and I should have thought, irresistibly".

Jane Austin read the book and told her sister that its emotional impact was sp strong that she fell in love with Clarkson. (9) Ralph Waldo Emerson argued the book was a turning point in history: "An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man... the Reformation, of Martin Luther; Quakerism, of George Fox, Methodism, of John Wesley; Abolition of Thomas Clarkson... All history resollves itself very easily into the biography of a few stout and earnest persons." (10)

Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade

In 1787 Clarkson, William Dillwyn and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as William Allen, John Wesley, Thomas Walker, John Cartwright, James Ramsay, Charles Middleton and William Smith gave their support to the campaign. Clarkson was appointed secretary, Sharp as chairman and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Hoare reported subscriptions of £136. (11)

The highly successful businessman, Josiah Wedgwood joined the organising committee. He urged his friends to join the organisation. Wedgwood wrote to James Watt asking for his support: "I take it for granted that you and I are on the same side of the question respecting the slave trade. I have joined my brethren here in a petition from the pottery for abolition of it, as I do not like a half-measure in this black business." (12)

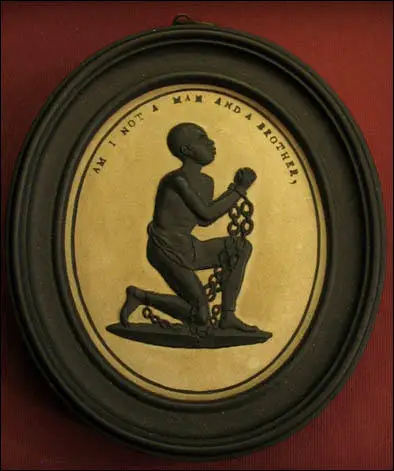

As Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has pointed out: "Wedgwood asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands beseechingly." It included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" Hochschild goes onto argue that "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks, the image was an instant hit... Wedgwood's kneeling African, the equivalent of the label buttons we wear for electoral campaigns, was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause." (13)

Thomas Clarkson explained: "Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and this fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom." (14)

Hundreds of these images were produced. Benjamin Franklin suggested that the image was "equal to that of the best written pamphlet".Men displayed them as shirt pins and coat buttons. Whereas women used the image in bracelets, brooches and ornamental hairpins. In this way, women could show their anti-slavery opinions at a time when they were denied the vote. Later, a group of women designed their own medal, "Am I Not a Slave And A Sister?" (15)

In 1787 Clarkson met Alexander Falconbridge, a former surgeon on board a slave ship. Clarkson described Falconbridge as an "athletic and resolute-looking man". Falconbridge was willing to testify publicly about the way slaves were treated. Clarkson later recalled: "Never were words more welcome to my ears. The joy I felt rendered me quite useless... for the remainder of the day." Falconbridge accompanied Clarkson to Liverpool where he acted as his bodyguard. Falconbridge later recalled: "His zeal and activity are wonderful but I am really afraid he will at times be deficient in caution and prudence, and lay himself open to imposition, as well as incur much expense, perhaps sometimes unnecessarily."

Falconbridge also gave evidence to a privy council committee, and underwent four days of questions by a House of Commons committee. He explained how badly the slaves were treated on the ships: "The men, on being brought aboard the ship, are immediately fastened together, two and two, by handcuffs on their wrists and by irons rivetted on their legs. They are then sent down between the decks and placed in an apartment partitioned off for that purpose.... They are frequently stowed so close, as to admit of no other position than lying on their sides. Nor will the height between decks, unless directly under the grating, permit the indulgence of an erect posture; especially where there are platforms, which is generally the case. These platforms are a kind of shelf, about eight or nine feet in breadth, extending from the side of the ship toward the centre. They are placed nearly midway between the decks, at the distance of two or three feet from each deck, Upon these the Negroes are stowed in the same manner as they are on the deck underneath." (16)

Clarkson attempted to show that the slave trade was highly dangerous. He claimed that of 5,000 sailors on the triangular route in 1786, 2,320 came home, 1,130 died, 80 were discharged in Africa and unaccounted for and 1,470 were discharged or deserted in the West Indies. Clarkson claimed that in Liverpool alone, over 15,165 seaman had been lost since 1771 in the 1,001 ships that had sailed from there to the coast of Africa.

Hugh Brogan has pointed out that in the pamphlet Clarkson argued that "far from being the nursery of British seamen, as its friends asserted, was in fact its graveyard, more seamen dying in that trade in one year than in the whole remaining trade of the country in two, and in the argument that slaves were not a necessary commodity for a flourishing trade with Africa." (17)

Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has argued: "When on 24 May 1787 Clarkson, the heart and soul of the campaign for abolition, presented the Committee for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade with evidence on the unprofitability of the business, he used rational arguments: an end of the traffic would save the lives of seamen (he had obtained much detail from a scrutiny of Liverpool customs records), encourage cheap markets for the raw materials needed by industry, open new opportunities for British goods, eliminate a wasteful drain of capital, and inspire in the colonies a self-sustaining labour force, which in time would want to import more British produce." (18)

William Wilberforce

Clarkson approached Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the anti-slavery group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." (19)

Wilberforce agreed that while people such as Thomas Clarkson worked on gathering evidence and mobilizing public opinion through the committee for the abolition of the slave trade, Wilberforce complemented their work through his exertions in the House of Commons. He also attempted lobbied bishops and prominent laymen. On 28th October, 1787, he wrote in his journal that "God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners". (20)

Charles Fox was also unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success." (21)

Political radicals such as Francis Place hated politicians such as Wilberforce "for their complacency and indifference to poverty in their own country while fighting against the same thing abroad". He described him as "an ugly epitome of the devil". (22) William Hazlitt added: "He preaches vital Christianity to untutored savages, and tolerates its worst abuses in civilised states. He thus shows his respect for religion without offending the clergy." (23)

In May 1788, Charles Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of Wilberforce Samuel Whitbread, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The legislation was initially rejected by the House of Lords but after William Pitt threatened to resign as prime minister, the bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July. (24)

Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has argued: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance". (25)

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying." (26)

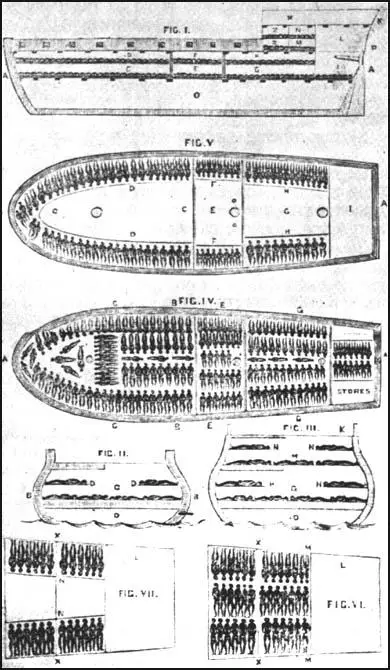

In 1789 Thomas Clarkson published a drawing of the slave-ship, The Brookes. It was originally built to to carry a maximum of 451 people, but was carrying over 600 slaves from Africa to the Americas. "Chained together by their hands and feet, the slaves had little room to move." It has been claimed that the "startling diagram was distributed far and wide and prints hung in every abolitionist home." (27)

Copies of this drawing was sent to members of the House of Commons committee to look into the issue of the slave trade. Thomas Trotter, a physician working on the slave-ship, Brookes, told the committee: "The slaves that are out of irons are locked spoonways and locked to one another. It is the duty of the first mate to see them stowed in this manner every morning; those which do not get quickly into their places are compelled by the cat and, such was the situation when stowed in this manner, and when the ship had much motion at sea, they were often miserably bruised against the deck or against each other. I have seen their breasts heaving and observed them draw their breath, with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which we observe in expiring animals subjected by experiment to bad air of various kinds." (28)

James Ramsay, the veteran campaigner against the slave trade, was now extremely ill. He wrote to Thomas Clarkson: "Whether the bill goes through the House or not, the discussion attending it will have a most beneficial effect. The whole of this business I think now to be in such a train as to enable me to bid farewell to the present scene with the satisfaction of not having lived in vain." Ten days later Ramsay died from a gastric haemorrhage. The vote on the slave trade was postponed to 1790. (29)

The French Revolution

William Wilberforce initially welcomed the French Revolution as he believed that the new government would abolish the country's slave trade. He wrote to Abbé de la Jeard on 17th July 1789 commenting that "I sympathize warmly in what is going forward in your country." Clarkson commented: "Mr. Wilberforce, always solicitous for the good of this great cause, was of the opinion that, as commotions have taken place in France, which then aimed at political reforms, it was possible that the leading persons concerned in them might, if an application were made to them judiciously, be induced to take the slave trade into their consideration, and incorporated among the abuses to be done away." (30)

Wilberforce intended to visit France but he was persuaded by friends that it would be dangerous for an English politician to be in the country during a revolution. Wilberforce therefore asked Clarkson to visit Paris on behalf of himself and the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson was welcomed by the French abolitionists and later that month the government published A Declaration of the Rights of Man asserting that all men were born and remained free and equal. (31)

However, the visit was a failure as Thomas Clarkson could not persuade the French National Assembly to discuss the abolition of the slave trade. Marquis de Lafayette said "he hoped the day was near at hand, when two great nations, which had been hitherto distinguished only for their hostility would unite in so sublime a measure (abolition) and that they would follow up their union by another, still more lovely, for the preservation of eternal and universal peace." Clarkson thought Lafayette "as uncompromising an enemy of the slave-trade and slavery, as any man I ever knew". (32)

On his return to England, Thomas Clarkson continued to gather information for the campaign against the slave-trade. Over the next four months he covered over 7,000 miles. During this period he could only find twenty men willing to testify before the House of Commons. He later recalled: "I was disgusted... to find how little men were disposed to make sacrifices for so great a cause." There were some seamen who were willing to make the trip to London. One captain told Clarkson: "I had rather live on bread and water, and tell what I know of the slave trade, than live in the greatest affluence and withhold it." (33)

Wilberforce believed that the support for the French Revolution by the leading members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade was creating difficulties for his attempts to bring an end to the slave trade in the House of Commons. He told Thomas Clarkson: "I wanted much to see you to tell you to keep clear from the subject of the French Revolution and I hope you will." Wilberforce had changed his views on the subject because of the way that radicals such as Thomas Paine had welcomed the French Revolution. (34)

Wilberforce's conservative friends were also very concerned about the other leaders of the anti-slavery movement. Isaac Milner, a leader of the Clapham Set, had a long talk with Clarkson, and then commented to Wilberforce: "I wish him better health, and better notions in politics; no government can stand on such principles as he maintains. I am very sorry for it, because I see plainly advantage is taken of such cases as his, in order to represent the friends of Abolition as levellers." (35)

Sierra Leone Company

Jonas Hanway established the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. This was an attempt to help black people living in London who had been victims of the slave trade. Simon Schama has argued in Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and Empire (2005) that the harsh winter of 1785-86 was one of the factors that encouraged Hanway to do something for the significant number of Africans living in poverty: "In the East End and Rotherhithe: tattered bundles of human misery, huddled in doorways, shoeless, sometimes shirtless even in the bitter cold or else covered with filthy rags." (36)

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that a black community should be allowed to to start a colony of free slaves in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. Thomas Clarkson was one of those who provided money for this venture.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets." (37)

Granville Sharp was able to persuade a small group of London's poor to travel to Sierra Leone. As Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has pointed out: "A ship was charted, the sloop-of-war Nautilus was commissioned as a convoy, and on 8th April the first 290 free black men and 41 black women, with 70 white women, including 60 prostitutes from London, left for Sierra Leone under the command of Captain Thomas Boulden Thompson of the Royal Navy". When they arrived they purchased a stretch of land between the rivers Sherbo and Sierra Leone. (38)

The settlers sheltered under old sails, donated by the navy. They named the collection of tents Granville Town after the man who had made it all possible. Granville Sharp wrote to his brother that "they have purchased twenty miles square of the finest and most beautiful country... that was ever seen... fine streams of fresh water run down the hill on each side of the new township; and in the front is a noble bay." (39)

The reality was very different. Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has argued: "The expedition's delayed departure from England meant that it had arrived on the African coast in the midst of the malarial rainy season.... The ground was another major problem: steep, forested slopes with thin topsoil... When they managed to coax a few English vegetables out of the ground, ants promptly devoured the leaves." (40)

Soon after arriving the colony suffered from an outbreak of malaria. In the first four months alone, 122 died. One of the white settlers wrote to Sharp: "I am very sorry indeed, to inform you, dear Sir, that... I do not think there will be one of us left at the end of a twelfth month... There is not a thing, which is put into the ground, will grow more than a foot out of it... What is more surprising, the natives die very fast; it is quite a plague seems to reign here among us." (41)

1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

On 18th April 1791 Wilberforce introduced a bill to abolish the slave trade. William Wilberforce was supported by William Pitt, William Smith, Charles Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, William Grenville and Henry Brougham. The opposition was led by Lord John Russell and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the MP for Liverpool. There was no reasoned justification of slavery or the slave-trade. Thomas Grosvenor, the MP for Chester, acknowledged that it was "not an amiable trade but neither was the trade of a butcher an amiable trade, and yet a mutton chop was, nevertheless, a good thing." One observer commented that it was "a war of the pigmies against the giants of the House". However, on 19th April, the motion was defeated by 163 to 88. (42)

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that the black community in London should be allowed to to start a colony in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. In the summer and autumn 1791 Wilberforce worked with his close friend Henry Thornton to launch the company. (43)

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets." (44)

Marriage

Thomas Clarkson was close friends with William Buck, a prosperous yarnmaker at Bury St Edmunds. He became acquainted with his daughter, Catherine Buck, in 1792. Clarkson was 32 and Catherine was only 20. According to one friend she had "dark bright eyes twinkling in her delicate mobile face which smiled all over." Ellen Gibson Wilson argues that: "She was a vivacious young woman, a gifted conversationalist... She was popular in West Suffolk ballrooms but prized as much for her wit as her beauty." (45)

Henry Crabb Robinson, was one of her close friends when she was a young woman. He later recalled that she had a strong interest in politics and loved to discuss the main issues of the day: "Her excellence lay rather in felicity of expression than in originality of thought. She was the most eloquent woman I have ever known, with the exception of Madame de Stael. She had a quick apprehension of every kind of beauty, and made her own whatever she learned."

Clarkson married Catherine at St. Mary's Church at Bury St Edmunds on 21st January 1796 and they went to live on his small estate at Eusemere on Ullswater. He renounced his Anglican orders, but although most of his political friends were Quakers, he decided against joining the Society of Friends. However, he attending the Penrith Quaker Meeting House and his wife, who in the past had been a free-thinker, read the works of George Fox. A friend commented: "She is become a religionist and a believer. Her faith receives little or no aid from written revelation - but God has spoken to her heart in a most sublime and mystical manner. In short she is of a species of Quaker."

In his book, The Great White Lie (1973), Jack Gratus argues that: "Clarkson... a large, rugged man, he was impatient and aggressive in manner with little sense of humour. He spoke as he wrote, ploddingly and pedantically, and both his readers and his acquaintances found he could be boring. His wife, in contrast, was a brilliant conversationalist and an excellent hostess." (46)

Clarkson's biographer, Hugh Brogan, has argued that "Clarkson's health was collapsing, and he had spent more than half his small capital in the cause of abolition. He decided to retire from the work; led by Wilberforce his friends raised £1500 in 1794 to compensate him for his disbursements." (47)

William Wilberforce wrote to one friend: "The truth is he has expended a considerable part of his little fortune, and though not perhaps very prudently or even necessarily yet I think, judging liberally, that he who has sacrificed so much time, and strength, and talents, should not be suffered to be out of pocket too. We should not look for inconsistent good qualities in the generality of men. Clarkson is ardent, earnest, and indefatigable, and we have benefited greatly from his exertions." (48)

On his farm at Eusemere Clarkson grew wheat, oats, barley, red clover and turnips and pastured sheep and cows. He sold his produce at Penrith market. He became fascinated with farming. He wrote in his journal: "The bud and the blossom, the rising and the falling leaf, the blade of corn and the ear, the seed-time and the harvest, the sun that warms and ripens, the cloud that cools, and emits the fruitful shower, these and a hundred objects afford daily food for the religious growth of the mind."

In November 1799 William Wordsworth, Dorothy Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge visited the Clarksons at Eusemere. The following month the Wordsworths moved into the Town End cottage at Grasmere. The two couples regularly visited each other. Catherine was quick to see Wordsworth's talent. She wrote: "I am fully convinced that Wordsworth's genius is equal to the production of something very great, and I have no doubt that he will produce something that posterity will not willingly let die, if he lives ten or twenty years longer."

Robert Southey was also a regular visitor to the Clarkson's home. He later wrote that Clarkson was a "man who so nobly came forward about the Slave Trade to the ruin of his health - or rather state of mind - and to the deep injury of his fortune...It agitates him to talk about the subject (slave trade) - but when he does - he agitates every one who hears him." Samuel Taylor Coleridge commented: "He has never more than one thought in his brain at a time, let it be great or small. I have called him the moral steam-engine, or the Giant with one idea."

Abolition of the Slave Trade Act

In March 1796, Wilberforce's proposal to abolish the slave trade was defeated in the House of Commons by only four votes. At least a dozen abolitionist MPs were out of town or at the new comic opera in London. Thomas Clarkson commented: "To have all our endeavours blasted by the vote of a single night is both vexatious and discouraging." Wilberforce wrote in his diary: "Enough at the Opera to have carried it. Very much vexed and incensed at our opponents". (49)

William Wilberforce held conservative views on most other issues. He opposed parliamentary reform and supported the suspension of Habeas Corpus that resulted in political activists such as Thomas Hardy and John Thelwall being imprisoned. He also supported the government when it passed Combination Acts of 1799–1800. This made it illegal for workers to join together to press their employers for shorter hours or may pay. As a result trade unions were thus effectively made illegal. (50)

In 1804 Thomas Clarkson returned to his campaign against the slave trade and toured the country on horseback obtaining new evidence and maintaining support for the campaigners in Parliament. A new generation of activists such as Henry Brougham, Zachary Macaulay and James Stephen, helped to galvanize older members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. (51)

William Wilberforce introduced an abolition bill on 30th May 1804. It passed all stages in the House of Commons and on 28th June it moved to the House of Lords. The Whig leader in the Lords, Lord Grenville, said as so many "friends of abolition had already gone home" the bill would be defeated and advised Wilberforce to leave the vote to the following year. Wilberforce agreed and later commented "that in the House of Lords a bill from the House of Commons is in a destitute and orphan state, unless it has some peer to adopt and take the conduct of it". (52)

In February 1805, Wilberforce presented his eleventh abolition bill to the House of Commons. Charles Brooke reported that the French slave trade was resurgent, so that abolition would merely hand British commerce over to the enemy. Wilberforce replied: "The opportunity now offered may never return, and if the present moment be neglected, events may occur which render the whole of the West India islands one general scene of devastation and horror. The storm is fast gathering; every instant it becomes blacker and blacker. Even now I know not whether it be too late to avert the impending evil, but of this I am quite sure - that we have no time to lose." This time the pro-slave trade MPs were better organised and it was defeated by seven votes. (53)

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. He had spoken against the slave-trade in nearly all the debates in the 1790s. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs. He added: "There was never perhaps a season when so much virtuous feeling pervading all ranks." (54)

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." Wilberforce praised the new, younger, members of Parliament "whose lofty and liberal sentiments... show to the people that their legislators, and especially the higher order of their youth, are forward to assert the rights of the weak against the strong." (55)

This time there was little opposition to Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15. In the House of Lords Lord Greenville made a passionate speech that lasted three hours where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville ... opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20. (56)

In 1807 Clarkson published his book History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade. He dedicated it to the nine of the twelve members of Lord Grenville's Cabinet who supported the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act and to the memories of William Pitt and Charles Fox. Clarkson played a generous tribute to the work of William Wilberforce: "For what, for example, could I myself have done if I had not derived so much assistance from the committee? What could Mr Wilberforce have done in parliament, if I ... had not collected that great body of evidence, to which there was such a constant appeal? And what could the committee have done without the parliamentary aid of Mr Wilberforce?"

In July, 1807, members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade established the African Institution, an organization that was committed to watch over the execution of the law, seek a ban on the slave trade by foreign powers and to promote the "civilization and happiness" of Africa. The Duke of Gloucester became the first president and members of the committee included Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Henry Brougham, James Stephen, Granville Sharp and Zachary Macaulay. The banker, Henry Thornton, became treasurer.

Wayne Ackerson, the author of The African Institution and the Antislavery Movement in Great Britain (2005) has argued: "The African Institution was a pivotal abolitionist and antislavery group in Britain during the early nineteenth century, and its members included royalty, prominent lawyers, Members of Parliament, and noted reformers such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Zachary Macaulay. Focusing on the spread of Western civilization to Africa, the abolition of the foreign slave trade, and improving the lives of slaves in British colonies, the group's influence extended far into Britain's diplomatic relations in addition to the government's domestic affairs. The African Institution carried the torch for antislavery reform for twenty years and paved the way for later humanitarian efforts in Great Britain." (57)

The African Institution complained about the negative view of Africans promoted by newspapers and books: "The portrait of the negro has seldom been drawn but by the pencil of his oppressor, and he has sat for it in the distorted attitude of slavery. If he be accused of brutal stupidity by one of those prejudiced witnesses, another taxes him with the most refined dissimulation and the most ingenious methods of deceit. If the negroes are represented as base and cowardly, they are in the same volume exhibited as braving death in the most hideous forms... Insensibility and excessive passion, apathy and enthusiasm, want of natural affection, and a fond attachment to their friends... are all ascribed to them by the same inconsistent pens." (58)

The establishment never forgave Clarkson for his work against the slave-trade. The Edinburgh Review reported: "It is impossible to look into any of Mr Clarkson's books without feeling that he is an excellent man - and a very bad writer... Feeling in himself not only an entire toleration of honest tediousness, but a decided preference for it upon all occasions ... he seems to have ... forgotten, that though dullness may be a very venial fault in a good man, it is such a fault in a book as to render its goodness of no avail whatsoever.... With all his philanthropy, piety, and inflexible honesty, he has not escaped the sin of tediousness - and that to a degree that must render him almost illegible to any but Quakers, reviewers, and others who make public profession of patience insurmountable. He has no taste, and no spark of vivacity - not the vestige of an ear for harmony - and a prolixity of which modern times have scarcely preserved any other example.... He has great industry - scrupulous veracity - and that serious and sober enthusiasm for his subject, which is in the long-run to disarm ridicule.... above all, he is perfectly free from affectation; so that, though we may be wearied, we are never disturbed or offended - and read on, in tranquility, till we find it impossible to read any more." (59)

William Wilberforce now spent his energies developing the Sierra Leone Company as a foundation for disseminating Christianity and civilization in Africa. It has been argued by Stephen Tomkins that during this period "Wilberforce... allowed the abolitionist colony of Sierra Leone... to use slave labour and buy and sell slaves.... After abolition, the British navy patrolled the Atlantic seizing slave ships. The crew were arrested, but what to do with the African captives? With the knowledge and consent of Wilberforce and friends, they were taken to Sierra Leone and put to slave labour in Freetown. They were called 'apprentices', but they were slaves. The governor of Sierra Leone paid the navy a bounty per head, put some of the men to work for the government, and sold the rest to landowners. They did forced labour, under threat of punishment, without pay, and those who escaped to neighbouring African villages to work for wages were arrested and brought back". (60)

Anti-Slavery Campaign

Ellen Gibson Wilson, the author of Thomas Clarkson (1989), has commented: "Clarkson in his prime was a handsome - some said majestic - figure, more than six feet tall with bold features and large, very blue and candid eyes. When he entered public life he wore a modish short and curled powdered wig, later his own thick and tousled hair which changed from red to white just as his face developed the furrows of care and conflict. He dressed habitually in black. In society, he made some people uncomfortable for he had little small talk and frequently withdrew into his own dark thoughts." (61)

It gradually became clear that there were serious problems with the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act. British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. In fact, the situation became worse. Now that the supply had officially ceased, the demand grew and with it the price of slaves. For high prices the traders were prepared to take the additional risks. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea. (62)

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. A new Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1823 by Thomas Clarkson, Henry Brougham and Thomas Fowell Buxton. "Its purpose was to rouse public opinion to bring as much pressure as possible on parliament, and the new generation realized that for this they still needed Clarkson.... He rode some 10,000 miles and achieved his masterpiece: by the summer of 1824, 777 petitions had been sent to parliament demanding gradual emancipation". (63)

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. "I now regret that I and those honourable friends who thought with me on this subject have not before attempted to put an end, not merely to the evils of the slave trade, but to the evils of slavery itself." (64)

William Wilberforce disagreed, he believed that at this time slaves were not ready to be granted their freedom. He pointed out in A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Addressed to the Freeholders and other inhabitants of Yorkshire that: "It would be wrong to emancipate (the slaves). To grant freedom to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters' ruin, but their own. They must (first) be trained and educated for freedom." (65)

In 1823 Wilberforce published his Appeal to the Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies. "In this pamphlet he dwelt on the moral and spiritual degradation of the slaves and presented their emancipation as a matter of national duty to God. It proved to be a powerful inspiration for the anti-slavery agitation in the country." (66)

Women and the Anti-Slavery Movement

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations. (67)

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders like Wilberforce. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods". (68)

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak on the same platforms as Heyrick and other women who favoured an immediate end to slavery. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain". (69)

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture". (70)

Thomas Clarkson was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions." (71)

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society. (72)

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). (64) The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions." (73)

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition. (74)

Wilberforce, who had always been reluctant to campaign against slavery, agreed to promote the organisation. Clarkson praised Wilberforce for taking this brave move. He replied: "I cannot but look back to those happy days when we began our labours together; or rather when we worked together - for he began before me - and we made the first step towards that great object, the completion of which is the purpose of our assembling this day." (75)

Clarkson redoubled his efforts and between October 1830 and April 1831, 5,484 petitions calling for an end to slavery was sent to Parliament. However, Clarkson had to wait until 1833 before Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act that gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. It contained two controversial features: a transitional apprenticeship period and compensation to owners totalling £20,000,000. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned. (76)

William Wilberforce died on 29th July 1833 at 44 Cadogan Place, Sloane Street. The following year Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce, began work on their father's biography. The book was published in 1838. As Ellen Gibson Wilson, the author of Thomas Clarkson (1989), pointed out: "The five volumes which the Wilberforces published in 1838 vindicated Clarkson's worst fears that he would be forced to reply. How far the memoir was Christian, I must leave to others to decide. That it was unfair to Clarkson is not disputed. Where possible, the authors ignored Clarkson; where they could not they disparaged him. In the whole rambling work, using the thousands of documents available to them, they found no space for anything illustrating the mutual affection and regard between the two great men, or between Wilberforce and Clarkson's brother."

Wilson goes on to argue that the book has completely distorted the history of the campaign against the slave-trade: "The Life has been treated as an authoritative source for 150 years of histories and biographies. It is readily available and cannot be ignored because of the wealth of original material it contains. It has not always been read with the caution it deserves. That its treatment of Clarkson, in particular, a deservedly towering figure in the abolition struggle, is invalidated by untruths, omissions and misrepresentations of his motives and his achievements is not understood by later generations, unfamiliar with the jealousy that motivated the holy authors. When all the contemporary shouting had died away, the Life survived to take from Clarkson both his fame and his good name. It left us with the simplistic myth of Wilberforce and his evangelical warriors in a holy crusade". (77)

Eventually, Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce apologized for what they had done to Clarkson: "As it is now several years since the conclusion of all differences between us, and we can take a more dispassionate view than formerly of the circumstances of the case, we think ourselves bound to acknowledge that we were in the wrong in the manner in which we treated you in the memoir of our father.... we are conscious that too jealous a regard for what we thought our father's fame, led us to entertain an ungrounded prejudice against you and this led us into a tone of writing which we now acknowledge was practically unjust." (78)

On 9th March 1837 Clarkson's son, was thrown out of his gig and killed instantly. His wife wrote to Henry Crabb Robinson: "It is true that under the infliction of so sudden and so sharp a blow I was at first incapable of receiving consolation from any earthly source." At the inquest it was discovered that a woman "not of good character" had been with him in the gig. A sum of £7 was distributed to keep this information out of the newspapers. (79)

Clarkson was painted by Benjamin Haydon in 1840. "Though Clarkson is a gentleman by birth and was educated like one, he is too natural for any artifice. He says what he thinks, does what he feels inclined, is impatient, childish, simple - hungry and will eat, restless and will let you see it; punctual and will hurry, nervous and won't be hurried, positive and hates contradiction, charitable, speaks affectionately of all, even of Wilberforce's sons, whose abominable conduct he lamented, more as if it cast a shadow over the father's tomb, than as if he felt wounded from what they had falsely said of himself." (80)

Thomas Clarkson's last few years were troubled by failing eyesight. He died at Playford Hall, near Ipswich on 26th September 1846. Alone among the leading abolitionists he was not immediately commemorated in Westminster Abbey. It is believed this was because of his closeness to the Society of Friends.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) Thomas Clarkson interviewed a sailor who worked on a slave-ship and published the account in his book, Essay on the Slave Trade (1789)

The misery which the slaves endure in consequence of too close a stowage is not easy to describe. I have heard them frequently complaining of heat, and have seen them fainting, almost dying for want of water. Their situation is worse in rainy weather. We do everything for them in our power. In all the vessels in which I have sailed in the slave trade, we never covered the gratings with a tarpawling, but made a tarpawling awning over the booms, but some were still panting for breath.

(2) Thomas Clarkson, History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1807)

Men in their first voyages usually disliked the trade; and, if they were happy enough then to abandon it, they usually escaped the disease of a hardened heart. But if they want a second and a third time, their disposition became gradually changed... Now, if we consider that persons could not easily become captains (and to these the barbarities were generally chargeable by actual perpetration, or by consent) till they had been two or three voyages in this employ, we shall see the reason why it would be almost a miracle, if they, who were thus employed in it, were not rather to become monsters, than to continue to be men."

(3) William Wilberforce, letter to Thomas Clarkson (August 1793)

We have long acted together in the greatest cause which ever engaged the efforts of public men, and so I trust we shall continue to act with one heart and one hand, relieving our labours as hitherto with the comforts of social intercourse. And notwithstanding what you say of your irreconcilable hostility to the present administration, and of my bigoted attachment to them, I trust if our lives are spared, that after the favourite wish of our hearts has been gratified by the Abolition of the Slave Trade, there may still be many occasions on which we may co-operate for the glory of our Maker, and the improvement and happiness of our fellow-creatures.

(4) Thomas Clarkson, History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1807)

For what, for example, could I myself have done if I had not derived so much assistance from the committee? What could Mr Wilberforce have done in parliament, if I ... had not collected that great body of evidence, to which there was such a constant appeal? And what could the committee have done without the parliamentary aid of Mr Wilberforce?

(5) Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade (1997)

When on 24 May 1787 Clarkson, the heart and soul of the campaign for abolition, presented the Committee for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade with evidence on the unprofitability of the business, he used rational arguments: an end of the traffic would save the lives of seamen (he had obtained much detail from a scrutiny of Liverpool customs records), encourage cheap markets for the raw materials needed by industry, open new opportunities for British goods, eliminate a wasteful drain of capital, and inspire in the colonies a self-sustaining labour force, which in time would want to import more British produce.

Clarkson set himself to gathering further information and spent the autumn of 1787 doing so. Though no one thought that the government would in the foreseeable future introduce a bill for the abolition of the trade, individual members, including officials, were (thanks to the help of Pitt) encouraging, and gave him access to invaluable state documents, including customs papers of the main ports. Clarkson went to Bristol. He described how on coming within sight of the city, just as night was falling, with the bells of the city's churches ringing, he "began now to tremble at the arduous task I had undertaken, of attempting to subvert one of the branches of the commerce of the great place which was then before me". But his despondency lessened, and he entered the streets "with an undaunted spirit." He inspected a slave ship, he talked to seamen, and he met Harry Gandy, a retired (and repentant) sailor who had been on a slave ship; but all retired captains avoided him as if he "had been a mad dog". The Deputy Town Clerk of Bristol obligingly told him, however, that "he only knew of one captain from the port in the slave trade who did not deserve to be hanged". Clarkson followed up the case of the murder of a sailor, William Lines, by his own captain. From Quaker informants Clarkson found evidence of the brutalities committed on a recently returning slaver, The Brothers, whose captain had tortured a free black sailor, John Dean. He received the testimony of a surgeon named Gardiner, about to sail to Africa on the ship Pilgrim. He talked to a surgeon's mate who had been brutally used on board the slave ship Alfred; and he gained information at first-hand of the terrible affair of the Calabar River in 1767. He also saw the inns where young men were made drunk, indebted, or both, and then lured to serve as sailors on slavers.

Clarkson went to Liverpool, too. In contrast to his experience in Bristol, Ambrose Lace and Robert Norris, both retired slave captains, did talk to him; the former had commanded the Edgar at the massacre at Calabar twenty years before. Clarkson also talked to slave merchants. He held a curious court in his inn, the King's Arms, at which, by now well informed, he engaged in argument with practitioners of the trade. Here, too, he pursued a murder case: in this instance, the affair of the steward, Peter Green, a flute-player, who had been whipped to death by his captain in the Bonny River with a rope, for no good cause. Clarkson was once threatened with assault on the quay, but his foresight in hiring a retired slave-ship surgeon from Bristol, Alexander Falconbridge, as his assistant and bodyguard preserved him from death.

(6) Katherine Plymley, diary entry on Thomas Clarkson (20th October 1791)

I was prepared to see with admiration a man who had now for some time given up all his own secular pleasure, and that too at a time of life when many think of little else, that he may dedicate his whole time to the glorious object of abolishing the African Slave trade... Whatever his external appearance and manners had been it would not have lessened my idea of him, as that was founded on the qualities of his head and heart which his conduct had established beyond a doubt - but I found him amiable and courteous in manners, above the middle size, well made and very agreeable in his person with a remarkable mildness of voice and countenance."

(7) The Edinburgh Review (July, 1813)

It is impossible to look into any of Mr Clarkson's books without feeling that he is an excellent man - and a very bad writer... Feeling in himself not only an entire toleration of honest tediousness, but a decided preference for it upon all occasions ... he seems to have ... forgotten, that though dullness may be a very venial fault in a good man, it is such a fault in a book as to render its goodness of no avail whatsoever.... With all his philanthropy, piety, and inflexible honesty, he has not escaped the sin of tediousness - and that to a degree that must render him almost illegible to any but Quakers, reviewers, and others who make public profession of patience insurmountable. He has no taste, and no spark of vivacity - not the vestige of an ear for harmony - and a prolixity of which modern times have scarcely preserved any other example.... He has great industry - scrupulous veracity - and that serious and sober enthusiasm for his subject, which is in the long-run to disarm ridicule.... above all, he is perfectly free from affectation; so that, though we may be wearied, we are never disturbed or offended - and read on, in tranquility, till we find it impossible to read any more.

(8) Ellen Gibson Wilson, Thomas Clarkson (1989)

The five volumes which the Wilberforces published in 1838 vindicated Clarkson's worst fears that he would be forced to reply. How far the memoir was Christian, I must leave to others to decide. That it was unfair to Clarkson is not disputed. Where possible, the authors ignored Clarkson; where they could not they disparaged him. In the whole rambling work, using the thousands of documents available to them, they found no space for anything illustrating the mutual affection and regard between the two great men, or between Wilberforce and Clarkson's brother. They had room, however, to exploit two highly personal incidents, involving Clarkson's letters about his financial subscription and his plea for his brother's promotion. These were written when Clarkson was shattered in mind and body. The Wilberforce's use of them attracted almost universal condemnation at the time...

The problem raised by the Wilberforce Life was identified by Henry Robinson. Not one in a hundred readers of the Life would be able to compare its account of the abolition campaign with Clarkson's History, published 30 years before. The Life has been treated as an authoritative source for 150 years of histories and biographies. It is readily available and cannot be ignored because of the wealth of original material it contains. It has not always been read with the caution it deserves. That its treatment of Clarkson, in particular, a deservedly towering figure in the abolition struggle, is invalidated by untruths, omissions and misrepresentations of his motives and his achievements is not understood by later generations, unfamiliar with the jealousy that motivated the holy authors. When all the contemporary shouting had died away, the Life survived to take from Clarkson both his fame and his good name. It left us with the simplistic myth of Wilberforce and his evangelical warriors in a holy crusade.

(9) Benjamin Haydon on Thomas Clarkson (1840)

Though Clarkson is a gentleman by birth and was educated like one, he is too natural for any artifice. He says what he thinks, does what he feels inclined, is impatient, childish, simple - hungry and will eat, restless and will let you see it; punctual and will hurry, nervous and won't be hurried, positive and hates contradiction, charitable, speaks affectionately of all, even of Wilberforce's sons, whose abominable conduct he lamented, more as if it cast a shadow over the father's tomb, than as if he felt wounded from what they had falsely said of himself.

(10) Robert Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce, letter to Thomas Clarkson (1842)

As it is now several years since the conclusion of all differences between us, and we can take a more dispassionate view than formerly of the circumstances of the case, we think ourselves bound to acknowledge that we were in the wrong in the manner in which we treated you in the memoir of our father.... we are conscious that too jealous a regard for what we thought our father's fame, led us to entertain an ungrounded prejudice against you and this led us into a tone of writing which we now acknowledge was practically unjust.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)