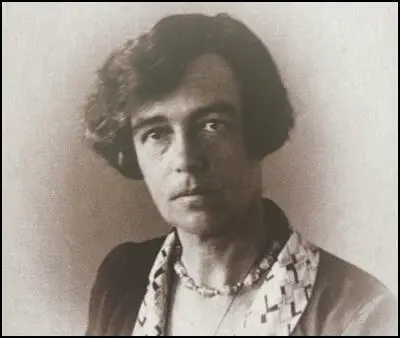

Margaret Haig Thomas

Margaret Haig Thomas was the only daughter of David Alfred Thomas and Sybil Haig Thomas, was born at Princes Square, Bayswater, on 12th June 1883. Margaret later wrote: "My father was disappointed: he wanted a boy". (1)

Her father was a successful industrialist and in 1888 became the Liberal MP for Merthyr Boroughs. His political career meant that she spent much time in London but their main home was a large house and estate at Llanwern, Monmouthshire. (2) The home in Llanwern had twelve rooms. They had a resident cook and a number of domestics. Margaret was taught by European governesses (French then German. Margaret spent a lot of time with her fourteen first cousins. She also spent a lot of time with two aunts, Janet Haig Boyd and Charlotte Haig. Like Sybil, the two aunts were strong feminists." (3)

Margaret attended Notting Hill High School before moving to St Leonards School. "Two years later I went to St. Leonards School, St. Andrews. This was at my own wish. I had discovered that at St. Leonards girls were allowed to go out for walks by themselves without attendant mistresses. This spelt freedom, and it was for freedom that I thirsted. I went to my father and told him what I wanted to do. Would he help? He was at first a shade doubtful. He knew little of girls' boarding schools, but his sister Mary had been to one, and he thought she had learnt to be silly there. The girls, he understood, used to flirt with the boys at an army crammer's next door." (4)

Sybil Haig Thomas took a strong interest in politics. In 1891 she became president of the Welsh Union of Women's Liberal Associations. She was also a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), under the leadership of Millicent Garrett Fawcettt. Some of her relatives, including her two sisters and her cousins, Florence Haig, Cecilia Wolseley Haig and Evelyn Haig, were supporters of the more militant, Women Social & Political Union. (5)

Debutante and University Student

On leaving school Margaret became a debutante. Her afternoons involved polite tea parties and many evenings were spent at dances. Her biographer, Angela V. John, points "By her own admission Margaret was awkward, plump and excruciatingly shy. She would have been happy to discuss political ideas or literature but had no appetite for small talk... The only time that balls were bearable was when cousins appeared." (6)

In an article that she wrote many years later, Margaret described the world of the debutante as a form of imprisonment: "The falsity and unreality of all its values, the cheapness and vulgarity of its standards and indeed of the whole atmosphere that pervades it, the stupidity of the conversation of its inmates are such it seems to me as no sane person should be asked to endure." (7)

In 1904 Margaret Haig Thomas went to Somerville College, Oxford University, to study history. Her reports do not suggest that she had any difficulty intellectually. After her first term she was described as "interesting and thoughtful". He essays were "always pleasant to read and she shows considerable ability." The report for the next term noted that she was "original and independent in thought" with "real intellectual power and a vivid imagination" but "not perhaps a remarkably hard worker". (8)

However, Margaret did not enjoy university life which she described to her friend, Winifred Peck as "this schoolgirl business". (9) Margaret was irritated by "the air of forced brightness and virtue that hung about the cocoa-cum-missionary-party-hymn-singing girls, and still more the self-conscious would-be-naughtiness of those who reacted from this into smoking cigarettes and feeling really wicked." (10)

Marriage

In April 1905, after only two terms at Somerville, Margaret Haig Thomas abandoned her studies. At this time she had fallen in love with Major Humphrey Mackworth, a man 12 years older than her. Despite their very different political and views they became engaged in 1907. They were married on 9th July 1908 at Trinity Church, Christchurch. It was an expensive and stylish wedding. The Western Mail commented that "the dresses were a feast". (11)

At first she attempted to please her husband. As her biographer pointed out: "There is one garment of clothing that neatly captures the symbolic and actual restrictions and constrictions that young ladies used to endure: the corset. When Margaret's mother broached the subject one summer holiday, her daughter reluctantly but obediently donned great whale-boned stays." Margaret later recalled: "I only paid a year's deference to my husband's wishes" and "cast them for good and all." (12)

It soon became clear that they were incompatible. He was a man of action who loved fox hunting and she loved reading books: "Humphrey held that no one should ever read in a room where anyone else wanted to talk. I, brought up in a home in which a father's study was sacred, held, on the contrary, that no one should ever talk in a room where anyone else wanted to read." (13)

Florence Haig

One of Margaret's aunts, Florence Haig, was an active member of the Women's Social & Political Union. On 11th February 1908, Florence and two of her artist friends, the sisters, Georgina Brackenbury and Marie Brackenbury, hid in a horse-drawn furniture van that took them to the door of the House of Commons, where they leapt out brandishing petitions. (14)

On the 30th June, 1908, she was selected to be a member of a deputation led by Emmeline Pankhurst from Caxton Hall, taking a resolution to the House of Commons demanding an immediate effective measure to give votes to women. During the procession several women were arrested. This included Florence Haig, Mary Postlethwaite, Maud Joachim, Florence Haig, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Mary Phillips, Jessie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Edith New, Mary Leigh, and Vera Wentworth. (15)

On 1st July, 1908, the women appeared in court. Mr Muskett, who appeared for the Metropolitan Police, said that there was really nothing new to be said in regard to these cases."Many ladies in the Union came there with the intention of being arrested." (16) Florence Haig said: "Mr. Asquith has shown us that peaceful demonstrations are useless." (17)

Mary Phillips argued that: "The government has forced women to adopt these tactics, and the Government is responsible for them." Elsie Howey said, "I don't think I obstructed the police, the police obstructed me." Had also a previous conviction. She had to said to a constable, "I am so glad you arrested me; I wanted to be arrested." Florence Haig was ordered to find a £20 surely or go to prison for a month. (18)

Zoe Proctor, a fellow prisoner, commented: "Miss Haig, whose hair nearly reached her ankles told me she had been given a small comb for use (in prison) which was of cause inadequate." (19) When she came out of prison she argued: "It is wonderful how each woman who acts influences her own circle. Friends who before may have been but mildly in favour, are converted into active and eager workers for the cause. Coming out is so delightful that the stupidity at the time in Holloway is forgotten." (20)

Women's Suffragette

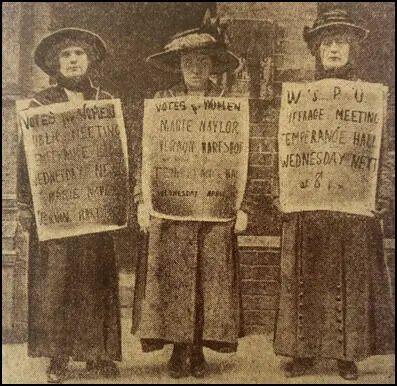

Margaret Haig Thomas was one of those who deeply influenced by her aunt going to prison. She announced to her mother, Sybil Haig Thomas, that she intended to join the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) procession to Hyde Park on 21st July 1908, Sybil decided to accompany her on the grounds "(a) she did not think an unmarried girl should walk unchaperoned through the gutter, (b) because she believed in votes for women". (21)

Shortly afterwards Margaret Haig Thomas joined the WSPU and set up its Newport branch. Her father, David Alfred Thomas, was a supporter of women's suffrage and had voted for it every time when it was proposed in the House of Commons. (22) However, he initially opposed his daughter joining the WSPU because he disliked its militant activities. He eventually told his daughter "he could be no judge of a matter which concerned one primarily as a woman". (23)

Her biographer, Deirdre Beddoe, has argued: "Though she was a firm believer in the justice of the cause, it was the promise of activity and excitement which most appealed to her. At last here was something which brought her to life". (24) Margaret herself said: "But for me and for many other young women like me, militant suffrage was the very salt of life. The knowledge of it had come like a draught of fresh air into our padded, stifled lives. It gave us release of energy, it gave us that sense of being some use in the scheme of things, without which no human being can live at peace. It made us feel that we were part of life, not just outside watching it." (25)

Margaret Haig Thomas worked closely with the Women's Freedom League and took part in an open-air meeting on women's suffrage at Cardiff docks in November 1909. Margaret and Muriel Matters attempted to address an increasingly hostile crowd from a trolley. David Alfred Thomas, concerned about the safety of his daughter, "forged his way through the immense gathering, and mounted the trolley". He also received considerable abuse and eventually the meeting was abandoned. The Western Mail reported that women had done "some silly things in their advocacy of the suffrage" but it deplored meetings being broken up. (26)

On 18th November 1909, Margaret Haig Thomas and Annie Kenney spoke at the Bowen Jenkins Memorial Hall, Aberdare, in the Merthyr Boroughs constituency. Attendance was restricted to members of the Liberal Party but the two women received hostile receptions. There was such a "cacophony of sounds - hoots, shouts, a shrill blast from a trumpet, cat-calls, a policeman's whistle and a rattle" that their words could not be heard. Men in the audience began throwing herrings, ripe tomatoes and cabbages at the women on the platform. (27)

Kenney appealed to her audience's beliefs: "Even if you object to our methods very strongly, you must, if you are Liberals and true to your principles, approve of our claims to the vote." This failed to keep the crowd quiet. Live mouse were set loose in the hall, along with sulphurated hydrogen gas, snuff and cayenne pepper. Eventually, the women walked out slowly from the back of the platform into the gymnasium and escaped in a cab. One newspaper called "it the most rowdy meeting" held in the town for at least thirty years." (28)

The following week Margaret arranged for Marion Wallace-Dunlop to speak at a meeting at the London Street Congregational Church in Maindee. On 25th June 1909, Wallace-Dunlop had been found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.” (29)

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail". (30)

Once again a near riot took place and Margaret Haig Thomas was forced to close the meeting when a bag of flour hit Wallace-Dunlop. Christabel Pankhurst declined the invitation but Emmeline Pankhurst bravely accepted the invitation. Margaret later recalled: "Every young hooligan in the town threatened joyously to come and break up the meeting" but they had not reckoned on "the power of a great speaker" who "held that audience in the hollow of her hand" and effectively silenced those who had come to jeer. (31)

Margaret Haig Thomas read several books on women's rights. This included Marriage as a Trade by Cicely Hamilton and Woman and Labour by Olive Schreiner, a book she described as "almost a bible to the pre-war generation of young women." (32) Margaret also wrote regular articles on women's suffrage for The Western Mail and the Monmouthshire Weekly Post. (33)

During the 1910 General Election the prime minister, Herbert Asquith declared in his East Fife constituency: "I have always been an opponent of women's suffrage. It is not good either for women or for the state." (34) Margaret Haig Thomas and Cecilia Wolseley Haig encountered him on his way to address a meeting at St. Andrews Town Hall at which no women were to be admitted. Margaret jumped onto the dashboard of Asquith's car and addressed him. She later recalled, he leaned back into the corner "looking white and frightened and rather like a fascinated rabbit". The crowd attacked the two women and had "their hats were tugged off, their clothes torn and their hair pulled down." Eventually they were rescued by three young golf caddies. (35)

Militant Action

Margaret Haig Thomas admired her cousins and aunts who had gone to prison during the struggle for women's suffrage. This included Florence Haig, Evelyn Haig, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Janet Haig Boyd and Charlotte Haig. Margaret suggested that prison for Florence was a pastime: she went "at such intervals as she could afford to spare from her own trade of portrait painting" and that Janet "went most regularly, never less than once a year." Margaret claimed that Janet insisted on greeting each clergyman with "How do you do - I've just come out of prison." (36)

Cecilia Wolseley Haig was one of those who received a beating from the police during the Black Friday demonstration. As the Votes for Women pointed out: "Miss Haig was entirely unaware of the presence of any illness, and, indeed, felt quite well. But on Black Friday, she was not only subjected to assault of a most disgraceful kind, but was also trampled upon." Her two unmarried sisters, Florence Haig and Evelyn Haig. nursed her but she died on 31st November 1911. (37)

Sylvia Pankhurst claimed that she died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Cecilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries." (38)

Margaret Haig Thomas gradually became convinced that women had to increase its militant activity if they were to obtain the vote. This included disrupting postal deliveries. In December, 1911, Emily Wilding Davison, set fire to three pillar boxes in Parliament Street in London. She was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison. This began a long campaign where Britain's 50,000 pillar boxes were targeted. On one weekend in March 1913 there were fourteen attacks on letter boxes in Cardiff alone. (39)

Laurence Housman revealed in his autobiography, The Unexpected Years (1937) that Margaret confessed to him about setting fire to pillar boxes when he was staying with David Alfred Thomas and Sybil Haig Thomas: "At dinner the increase of militancy was being discussed, and, in certain of its forms, condemned. Only that week a local letter box had been set on fire; it was the latest form that militancy had then taken; and in that high social circle it was not approved: it was hoped that the perpetrators would be caught and punished. My host's daughter was sitting next to me: she gave me a soft nudge. 'I did it', she said." (40)

In December 1912 there were several local newspaper reports of Newport's pillar boxes being attacked. The glass tubes containing acid were labelled "Votes for Women". The following year Margaret Haig Thomas visited the Women's Social & Political Union headquarters in London. She was given twelve long glass tubes with corks. Six contained phosphorous and the other six held a chemical compound. When mixed together they produced flames. "She travelled home in a crowded third-class railway compartment with her incendiary materials in a flimsy covered basket on the seat beside her." (41)

On 25th June, 1913, she placed two of the tubes in a foolscap envelope and took a tram for the five-mile journey to Newport. "My heart was beating like a steam engine, my throat was dry, and my nerve went so badly that I made the mistake of walking several times backwards and forwards past the letter box before I found the courage to do it... I smashing them on the inside edge of the letter box as one let them drop. It looked to other passers-by exactly as if one were posting a letter." (42)

Within a few minutes, smoke could be seen coming from the letter box. Water from a nearby house was used to extinguish the smoke and flames and a postman saved some of the letters. The next day, as she was on her way from her house to a tea party in Llanwern village, Detective-Sergeant Caldecott and Police Constable King arrested her and took her to the police station. Margaret was locked in a cell with a wall covered in vomit. It smelt like a urinal. Margaret was locked in a cell with a wall covered in vomit. It smelt like a urinal. Charlotte Haig offered to stand bail, but this was refused and she remained there for over four hours until her husband arrived to pay £100 bail money. (43)

Margaret's trial took place on 11th July, 1913. Margaret pleaded "Not Guilty" as the WSPU required but "made no special effort to pretend that I had not done the thing". (44) It was argued in court that the contents of the tube had been prepared "by a chemist of exceedingly great ability" and it damaged eight letters and five postcards. Margaret was found guilty and fined £10 plus 10s costs. Margaret refused to pay her fine or allow others to pay for her and she was sentenced to a month in the county gaol at Usk. (45)

Margaret went on hunger-strike. "I had made up my mind that I would not touch food whilst I was in prison. I had further decided that in order to hurry on the time when I should be weak enough to be let out I would refuse drink for as long as I could; but would take it if and when I found my thirst unendurable... I did not feel particularly hungry, but I did get terribly thirsty. By the end of three days I had reached the stage where I had difficulty in restraining myself from drinking the contents of the slop pail." The authorities were concerned about her health and released her on the sixth day under the terms of the Cat & Mouse Act. (46)

On the day that her licence expired Margaret Haig Thomas fine was mysteriously paid. It has been assumed, but never proved, that her husband paid the money. On the same day an inaugural meeting of a branch meeting of the Church League for Women's Suffrage was held in a local hall. Sybil Haig Thomas was one of the organisers. Margaret attended and, according to the press "seemed to be quite recovered from the effects of her hunger strike."When asked about the payment, she replied that the fine had been paid contrary to her wishes. (47)

First World War

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided". (48)

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy." (49)

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!". (50) Margaret Haig Thomas accepted the decision by the WSPU leadership to abandon its militant campaign for the vote. Her parents gave over part of the house at Llanwern as a hospital. (51)

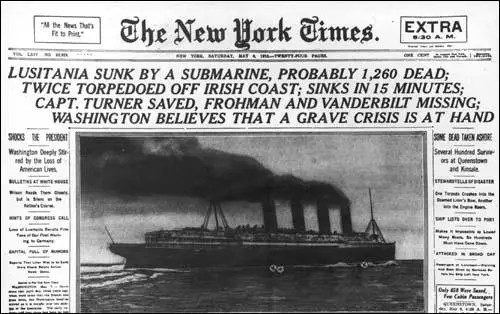

In March 1915, David Alfred Thomas went on a seven-week business trip with his daughter, Margaret to New York. They both decided to come home on the Lusitania, the largest and fastest passenger ship in commercial service. It was 750ft long, weighed 32,500 tons and was capable of 26 knots. It left New York harbour for Liverpool on 1st May, 1915. However, it was going to be a dangerous journey. (52)

On 4th February, 1915, Admiral Hugo Von Pohl, sent a order to senior figures in the German Navy: "The waters round Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, are hereby proclaimed a war region. On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening. Neutral ships will also incur danger in the war region, where, in view of the misuse of neutral flags ordered by the British Government, and incidents inevitable in sea warfare, attacks intended for hostile ships may affect neutral ships also." (53)

Soon afterwards the German government announced an unrestricted warfare campaign. This meant that any ship taking goods to Allied countries was in danger of being attacked. This broke international agreements that stated commanders who suspected that a non-military vessel was carrying war materials, had to stop and search it, rather than do anything that would endanger the lives of the occupants. This message was reinforced when the German Embassy issued a statement on its new policy: "Travellers intending to embark for an Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that in accordance with the formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her allies are liable to destruction in those waters; and that travellers sailing in the war zone in ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk." (54)

Most of the passengers were aware of the risks they were taking. Margaret Haig Thomas later recalled that in New York City during the weeks preceding the voyage "there was much gossip of submarines". It was "stated and generally believed that a special effort was to be made to sink the great Cunarder so as to inspire the world with terror". On the morning that the Lusitania set sail the warning that had been issued by the German Embassy on 22nd April 1915, was "printed in the New York morning papers directly under the notice of the sailing of the Lusitania". Margaret commented that "I believe that no British and scarcely any American passengers acted on the warning, but we were most of us very fully conscious of the risk we were running." (55)

At 1.20pm on 7th May 1915, the U-20, only ten miles from the coast of Ireland, surfaced to recharge her batteries. Soon afterwards Captain Schwieger, the commander of the German U-Boat, observed the Lusitania in the distance. Schwieger gave the order to advance on the liner. The U20 had been at sea for seven days and had already sunk two liners and only had two torpedoes left. He fired the first one from a distance of 700 metres. Watching through his periscope it soon became clear that the Lusitania was going down and so he decided against using his second torpedo. D. A. Thomas and his daughter were just leaving the first-class dining-room when the ship was hit. (56)

William McMillan Adams was travelling with his father. "I was in the lounge on A Deck when suddenly the ship shook from stem to stem, and immediately started to list to starboard. I rushed out into the companionway. While standing there, a second, and much greater explosion occurred. At first I thought the mast had fallen down. This was followed by the falling on the deck of the water spout that had been made by the impact of the torpedo with the ship. My father came up and took me by the arm. We went to the port side and started to help in the launching of the lifeboats." (57)

David Alfred Thomas became separated from his daughter when she went back to the cabin to get their lifebelts. When she returned she could not find her father. He had managed to get onto the last lifeboat that was launched. As it drew away, the ship slowly sank and the lifeboat narrowly missed being hit by its funnel. After rowing for two and a half hours a small steamer took the survivors on board. (58)

Margaret was unable to get into a lifeboat: "It became impossible to lower any more from our side owing to the list on the ship. No one else except that white-faced stream seemed to lose control. A number of people were moving about the deck, gently and vaguely. They reminded one of a swarm of bees who do not know where the queen has gone. I unhooked my skirt so that it should come straight off and not impede me in the water. The list on the ship soon got worse again, and, indeed, became very bad. Presently the doctor said he thought we had better jump into the sea. I followed him, feeling frightened at the idea of jumping so far (it was, I believe, some sixty feet normally from A deck to the sea), and telling myself how ridiculous I was to have physical fear of the jump when we stood in such grave danger as we did. I think others must have had the same fear, for a little crowd stood hesitating on the brink and kept me back. And then, suddenly, I saw that the water had come over on to the deck. We were not, as I had thought, sixty feet above the sea; we were already under the sea. I saw the water green just about up to my knees. I do not remember its coming up further; that must all have happened in a second. The ship sank and I was sucked right down with her." (59)

After about two and three quarter hours in the water before being picked up by a rowing boat. She was unconscious and at first she was presumed dead and was dumped on the deck of a small steamer called the Bluebell. Luckily a midshipment thought there was possibly "some life in this woman" and attended to her. Margaret regained consciousness at about 9.30pm. "She was lying naked wrapped in blankets on a ship's deck in the dark. Shaking violently, her teeth were 'chattering like castanets' and she felt acute back pain." However, she was in her early thirties and had a strong physique and survived the ordeal. (60) D. A. Thomas later told The Western Mail, "If I had lost her (Margaret) my life would have been blighted for ever, and everything would have become a blank for the future. She is more than a daughter to me; she is a real pal." (61)

Of the 2,000 passengers on board, 1,198 were drowned, among them 128 Americans. (62) The German newspaper Die Kölnische Volkszeitung supported the decision to sink the Lusitania: "The sinking of the giant English steamship in a success of moral significance which is still greater than material success. With joyful pride we contemplate this latest deed of our Navy. It will not be the last. The English wish to abandon the German people to death by starvation. We are more humane. we simply sank an English ship with passengers, who, at their own risk and responsibility, entered the zone of operations." (63)

As Deirdre Beddoe has pointed out: "The ordeal made Margaret determined to play her own part in the war effort. She was appointed as commissioner of Women's National Service in Wales, as controller of women's recruiting and, before the war ended, to the Women's Advisory Council of the Ministry of Reconstruction, which was concerned with issues on which she felt strongly. She was committed to the idea that women should remain an integral part of the post-war workforce, and to that end she set up the Women's Industrial League in 1918 to campaign for the rights of women workers. (64)

background is the Lusitania (left) and Usk Gaol (c. 1915)

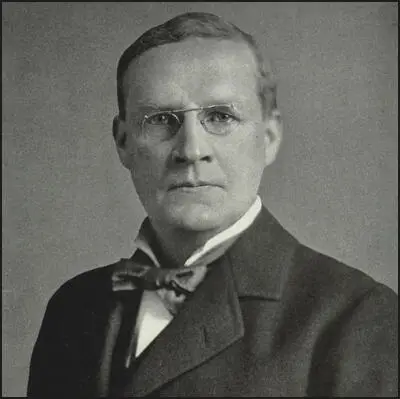

In June 1915, David Lloyd George, Munitions Minister, asked David Alfred Thomas to go to back to the United States to arrange supplies of munitions. Lloyd George explained to the House of Commons: "I felt, in consequence of the great importance of the American and Caadian markets and of the innumerable offers which I have received, directly and indirectly, to provide shell munitions of war from Canada and the United States of America, it was very desirable that I should have someone there who, without loss of time, which must necessarily take place when all your business is transacted by means of cable, should be able to represent the Munitions Department in the transaction of business there and find out exactly the position. I propose to send over, on behalf of the Munitions Department, a gentleman who was once a member of this House - a very able business man. He has business relations with America on a very considerable scale, and I propose to ask Mr. D. A. Thomas to go over to America for the purpose of assisting us in developing the American market." (65)

David Alfred Thomas admitted that it was a daunting prospect as he could not ride himself of memories of the Lusitania and told Lloyd George of his fears. He replied he could not think of an efficient substitute. Less than two months after his ordeal at sea, Thomas sailed from Liverpool on the St Louis. This time, his wife, Sybil Haig Thomas, insisted on going with him. They were escorted through the danger zone by two British destroyers. On arrival in New York, he was met by the British Ambassador. He was guarded by detectives as they feared he might be assassinated by German sympathisers. Thomas was away from home for five months. (66)

In 1916, David Lloyd George appointed D. A. Thomas as the President of the Local Government Board. He found the experience frustrating as his attempts to establish a separate Ministry of Health ended in failure. (67) In March 1917 he complained of a pain in his heart. A heart specialist diagnosed angina and recommended he resign from the government and then he could live until he was ninety. (68)

Thomas did not take this advice but he did initially refuse to take the job as Minister of Food Control. Conscious of the difficulty of refusing a post in the midst of war, he took office in June 1917. (69) In this new post he worked extremely long hours in a department of 5,000 employees and his daughter later claimed he "often started work a 3 or 4 am in the morning". (70) The actions that Thomas took reduced people's food allowances. The Evening Standard commented: "No Minister has achieved the quite the same popularity as the Minister who ruthlessly cut down the people's food allowances." (71)

Margaret Haig Thomas was appointed as commissioner of women's national service in Wales, as controller of women's recruiting and, before the war ended, to the Women's Advisory Council of the Ministry of Reconstruction, which was concerned with issues on which she felt strongly. She wrote: "Nothing in the whole conduct of the War has been more striking than the readiness and the ability of the women in nearly all the belligerent nations to render invaluable service to their respective countries, and nothing has been stranger than the slowness of various Governments to realise the vast capacity of the resources upon which they might draw." (72)

In 1918 Helen Archdale became Margaret's assistant at the Ministry of National Service, dealing with correspondence, card indexing and contacting and classifying details of women available for naval, military and air service. After the death of her husband, Archdale became Margaret's personal secretary. Archdale's three children were boarding at Bedales School and Margaret was paying their school fees. Elizabeth Robins suggested that the two women had become lovers. (73)

Viscountess Rhondda

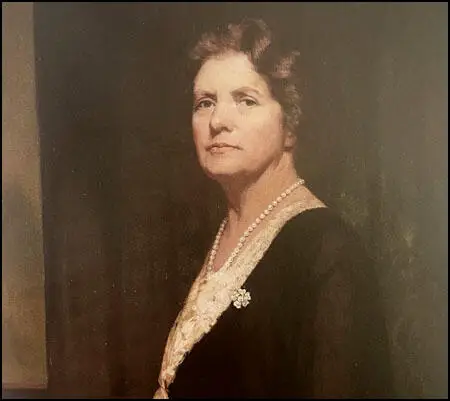

Just after his sixty-second birthday David Alfred Thomas contracted pleurisy and spent April and May in bed or in a chair in the garden. Thomas tried to resign but the offer was refused. On 3rd June 1918, Thomas was promoted to the rank of Viscount for his service as Food Controller and King George V agreed "that the Remainder of your peerage should be settled upon your daughter... in cases where the service rendered to the State is very conspicuous". (74)

David Alfred Thomas died of heart disease and rheumatic fever on on 3rd July, 1918. David Lloyd George told a memorial service three days later that his efforts represented "one of the most distinctive triumphs of the war". (75) The Daily Telegraph declared: "When history completes its record of the leaders who baffled Prussia's ambition for the mastery of the world a distinguished place will be given to Lord Rhondda." (76) He left £20,000 to Gonville and Caius College to provide "Rhondda Scholarships." (77)

As Deirdre Beddoe pointed out: "Margaret was left an extremely wealthy woman. Lord Rhondda's estate was valued at £885,645: she inherited his property, his commercial interests, and his title. Margaret inherited his property, his commercial interests, and his title. The Directory of Directors for 1919 listed Viscountess Rhondda, as she now was, as the director of thirty-three companies (twenty-eight of them inherited from her father) and chairman or vice-chairman of sixteen of these. Already a famous figure whose activities were widely reported in the London press on account of her business career and of her increasingly leading role as a spokeswoman for feminism." (78)

Crystal Eastman argued that this was a success for feminism: "Viscount Rhondda left to his daughter not only his title but full possession, direction and control of his extensive properties, exactly as though she had been a son. She inherited not only his money but his directorships, his active place in the financial world.... No, it was not radicalism that led Lady Rhondda to attack the idle women of her own class, it was feminism. She is a feminist, heart and soul, consistent to the last degree." (79)

Time and Tide

Margaret Haig Thomas decided to use some of her wealth to publish the feminist political magazine Time and Tide. The first edition was published on 14th May 1920: "Women have newly come into the larger world, and are indeed themselves to some extent answerable for that loosening of party and sectarian ties which is so marked a feature of the present day. It is therefore natural that just now many of them should tend to be especially conscious of the need for an independent press, owing allegiance to no sect or party. The war was responsible for breaking down the barriers which kept each individual or group of individuals in a watertight compartment. The past five years have taught the importance of that wider view which sees the part in relation to the whole. There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women - the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings." (80)

Its masthead included a drawing of the tidal River Thames below the House of Parliament and Big Ben. This signified the magazine's interest in Westminster politics. Margaret wanted it to have a similar impact to the New Statesman. She hoped it would "mould the opinion" not of the masses but of what she called "the keystone people", the vanguard who in turn would influence and guide the many. (81)

According to Deirdre Beddoe: "Time and Tide was for Lady Rhondda the fulfilment of a childhood dream. It was her grand passion, to which she devoted all her energies, at the expense of her business interests and her health. Though it was nominally owned by a limited company (the Time and Tide Publishing Company) and incorporated with £20,000 capital, Lady Rhondda subsidized the journal from the outset. She controlled 90 per cent of the shares, was at first vice-chairman, then chairman of directors." (82)

Lady Rhondda believed that the major problem that women faced was the scale of the prejudice which fuelled the opposition to attempted reforms. She maintained that after the war the women's movement was engaged in two battles, to achieve legislative progress for women and to change public opinion. (83)

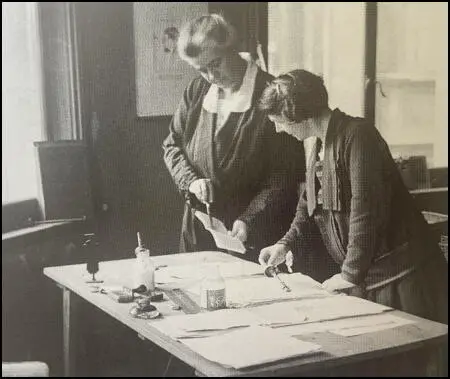

Time and Tide was edited by Margaret's lover, Helen Archdale who had been a fellow member of the Women's Social & Political Union who had spent two months in Holloway after participating in the mass window-breaking in 1911. After becoming the WSPU prisoners' secretary and worked on The Suffragette where she gained compositing and editing skills that helped her in her new job. (84)

Helen Archdale (on the left) at the Time offices (c. 1922)

Time and Tide argued throughout the 1920s that it was a mistake for women to join parties while they remained so low down the political agenda. "Instead women should somehow band together as voters and force the parties to change their priorities... As the 1920s wore on it was increasingly reduced to criticising the parties for failing to place women in winnable seats and women politicians for giving excessive loyalty to their male leaders." (85)

However, she did praise the Labour Party for creating women's sections. In doing so it attracted 100,000 women members. (86) Barbara Ayrton Gould wrote: It is large; it is going to become larger; and it is new. Consider the importance of that. Men voters are still bound fast in the hoary and Tory traditions of the old-established Parties... Women... simply because they are newcomers to politics are free from this constraint." (87)

Lady Rhondda believed that "it is the strength of the non-party women's organisations rather than the number of women attached to the party organisations which is likely to decide the amount of interest taken by the parties in women's questions." (88)

Although the journal could be described as a success, it never developed into a major weapon for feminism. Lady Rhondda's critics complained that she developed an elitist strategy. At a time when 8 million women had recently obtained the vote, she showed no sign of wanting it to be read by a wide public. She later wrote she intended it to be a "first-class review" that was "read by comparatively few people, but they are the people who count, the people of influence". (89)

Six Point Group of Great Britain

In January 1921 Lady Rhondda and Helen Archdale launched the Six Point Group of Great Britain. "We have recently passed the first great toll-bar on the road which leads to equality, but it is a far cry yet to the end of the road, and our present position is not yet altogether a satisfactory one from the point of view of the country as a whole. We have, as a fact, achieved a half-way position, and that is never a position which makes for stability." (90)

Lady Rhondda argued that women were moving in the right direction yet still had some way to travel on the long road to equality, she was placing a special responsibility onto newly enfranchised women (who now constituted over a third of the electorate) to complete the task that others had started for them. (91)

The group focused on what she regarded as the six key issues for women: The six original specific aims were: (i) Satisfactory legislation on child assault; (ii) Satisfactory legislation for the widowed mother; (iii) Satisfactory legislation for the unmarried mother and her child; (iv) Equal rights of guardianship for married parents; (v) Equal pay for teachers and (vi) Equal opportunities for men and women in the civil service. (92)

The Six Point Group (SPG) was formally inaugurated on 17th February 1921. It had monthly meetings at its headquarters on the top floor of 92 Victoria Street. Other members included Ethel Annakin Snowden (vice-president), Elizabeth Robins, Cicely Hamilton, Stella Newsome, Rebecca West, Helen Archdale, Frances Balfour, Charlotte Marsh, Theresa Garnett, Winifred Mayo, Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain. The SPG Parliamentary committee of supportive MPs was chaired by Philip Snowden. At the time there were only two women MPs: Nancy Astor and Margaret Winteringham. (93)

in 1925. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stands on her right and Elizabeth Robins on her left.

The SPG drew up "black and white lists" of MPs which were compiled on the basis of previous record on women's issues in the House of Commons. Cheryl Law argues in Suffrage and Power: The Women's Movement, 1918-1928 (2000): "It informed its readers that additional information was available on request from the SPG. It was an ingenious tactic, presented in a readily comprehended format, and the advantage over questionnaires of being compiled without actual recourse to the MPs." (94)

Women were urged to set aside party loyalty and work to defeat the "Blacklisted" members. After the 1922 General Election the SPG was able to report that of 23 MPs on the Blacklist 9 had been defeated, 2 stood down and only 12 had been re-elected. Martin Pugh argues: "In practice, however, this was only a shade more coercive than the pressure being applied by the constitutionists at this time, though their emphasis was perhaps rather more on supporting friends of women's causes." (95)

The SPG aattempted to persuade the political parties to have more women stand in winnable seats. Time and Tide pointed out: "When the women get defeated... the parties who have thus used them are the first to turn round and say: 'There is no use putting up women candidates, they only get defeated'... It should be remembered that there is no generosity in offering a woman the chance of fighting a hopeless seat on condition that she pays her own expenses." (96)

The House of Lords

On the death of David Alfred Thomas the prime minister David Lloyd George, explained the King George V had agreed that would be settled upon his daughter Lady Rhondda. Since Margaret had battle for her claim."no children the title did not last beyond her generation, but she was determined that a peerless should be entitled to exercise the same rights as a peer. When it was announced that she intended to take her place in the House of Lords the Manchester Guardian that she "sallied forth to do battle for her claim". (97)

On 4th April 1919, William Adamson, the leader of the Labour Party introduced the Women's Emancipation Bill: As he explained: "It is a small Bill, and provides for the removal of certain restraints and disabilities which are still imposed upon women. Clause 1 of the Bill seeks to remove the disqualification that stands against women holding civil and judicial appointments. Clause 2 seeks to amend the Representation of the People Act, 1918, in a manner that will place women upon an equal footing with men, and Clause 3 seeks to remove the disqualifications which prevent them from sitting and voting in the House of Lords on the same footing as they are now entitled to sit and vote in the House of Commons." (98)

This legislation was superseded by the governments's Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill. The Lord Chancellor, Robert Finlay, 1st Viscount Finlay, moved an amendment in the House of Lords, claimed that the clause relating to peeresses had only been inserted so that the Lords might express their views. After a debate on the issue the clause was dropped. Lady Rhondda organised a petition that was presented to the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords. (99)

On 2nd March 1922 her case was heard before Richard Hely-Hutchinson, 6th Earl of Donoughmore and seven other peers. After some debate the Committe ruled seven to one that it was "very much in agreement with what had been urged" and could not imagine "any sound agreement to the contrary of what is being asked by the petitioner. When one looks at the plain words of the Act, at the date . of the Act, and at the legislation which hads gone before, the conclusion would appear to be irresistible." (100)

Women campaigners immediately declared victory. Lady Frances Balfour told the National Council of Women that "the collapse of the walls of opposition fell down before Lady Rhondda". The Church Times called it a "remarkable triumph for feminism". The Manchester Evening News asked if Lady Rhondda had paved the way for a "Lady Archbishop or Lord Chancellor". The Western Mail heralded this change in the law and said it was "inconceivable that the House of Lords would reject the Committee's decision, based as it is on the interpretation of a statute." (101)

Lady Rhondda realised that the battle had not been won. Time and Tide suggested that "backwoodsmen" amongst the peers would put up a strong fight. (102) Lady Rhondda told the Spectator magazine that "I am not in the House of Lords yet and I am afraid the Lord Chancellor is going to move against me". (103)

On 30th March 1922, Richard Hely-Hutchinson, 6th Earl of Donoughmore, moved that the report be accepted by the House of Lords. the Lord Chancellor, Frederick Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, moved an amendment to refer the matter back to the Committee for Privileges for "reconsideration". Birkenhead argued that the original Committee for Privileges had heard what he called an "ingenious" and "full argument" in favour of the claim, they had not considered arguments to the contrary. He also requested that the committee be considerably enlarged and that he should sit on it. (104)

Charlotte Haldan called for the House of Lords to keep to the original decision: "Lady Rhondda is the most remarkable businesswoman in the world. She is a most feminine creature of the greatest outward simplicity, whose soft grey eyes and light brown hair were matched in their gentleness only by the charm of her low, even, and tranquil voice. If she wins her battle for the right to take her seat in the House of Lords she will have created another record, and added another victory to her championship of women's equality." (105)

Thirty men, including several lords who played an active role in the campaign opposing women's suffrage sat on the augmented Committee for Privileges. Sir Gordon Hewart, the Liberal Party MP and former Attorney General, had recently been appointed as the Lord Chief Justice, was a supporter of Lady Rhondda, but was now no longer involved in the issue. His replacement, Sir Ernest Pollock, the Conservative Party MP, was a long-term opponent of women's suffrage. Birkenhead and Pollock argued that an act of Parliament was to be interpreted strictly according to its wording or whether the intentions of the legislators should also be taken into account. Lady Rhondda's claim was rejected by a majority of twenty to four with six abstentions. (106)

George Bernard Shaw commented: "Lady Rhondda is the terror of the House of Lords. She is a peeress in her own right. She is also an extremely capable woman of business, and the House of Lords has risen up and said, 'If Lady Rhondda comes in here, we go away!' They feel there would be such a show-up of the general business ignorance and imbecility of the malesex as never was before." (107)

Helen Archdale

Lady Rhondda had not lived with her husband Major Humphrey Mackworth for many years. Since 1918 she had lived with Helen Archdale. Lady Rhondda divorced Major Mackworth on the grounds of his desertion and misconduct in December 1922. Although she got support from many of her colleagues in the women's suffrage movement, some people criticised her for divorcing her husband. Helen Archdale's daughter Betty, claimed that a lot of Margaret's friends ostracised her as a result of her divorce. (108)

Margaret and Helen lived together in Chelsea Court. Betty Archdale pointed out that although the break-up of her marriage "hurt Margaret enormously" she "found the personal help she needed in mother". Helen admitted that she found motherhood "greatly overrated, greatly sentimentalised." The two women shared an interest in journalism and worked very closely with Time and Tide. (109)

The two women lived in London but every weekend they would travel to Chart Cottage in Watery Lane, Seal Chart, near Sevenoaks. In 1925 they moved to Stonepitts Manor House closeby. (110) The house had seven bedrooms. The gardens were enclosed within high, red-brick walls and included a tennis court, rose gardens, rock gardens and a kitchen garden. The two women often had literary figures staying for the weekend: "Everyone wrote, read and talked as they liked. The result was some marvellous conversation and really gracious living." (111)

Lady Rhondda and Helen Archdale often had political disagreements and increasing editorial interventions, resulted in her being effectively forced out of the editorship of Time and Tide in 1926. Although she remained a director of Time and Tide Publishing Company, "after her resignation specifically feminist concerns were gradually marginalized in" the magazine. (112)

Although the two women continued to live together the relationship was in difficulty. In a letter written in November, 1926, Margaret commented: "I don't know whether you ever ask yourself why we live together; if you ever go back to the time when we first came together. We began it for the only reason that can make living together possible, because we were very fond of one another. I have paid heavily for believing that your love, that seemed a real thing, was real - when in fact it can only have been a passing surface passion, much as I've seen you several times. I gave all I had to give and for years now I have been struggling not to see, what you were making only abundantly clear, that the only value I had in your eyes was as some one who could give the children treats." (113)

The two women continued to live together but Lady Rhondda resented the fact that she was paying all the bills: "I very much dislike spending a lot of money when I am already living beyond my income as I am these bad years". (114) They still spent times together at Stonepitts Manor House but as Helen explained to a friend "we do not necessarily go together in fact it is rarely that we coincide." It was not until the spring of 1931 that Helen left the house for good. (115)

Theodora Bosanquet

Theodora Bosanquet was executive secretary to the International Federation of University Women when she first met Lady Rhondda. In 1927 she began reviewing regularly for Time and Tide. Extracts of her study of Harriet Martineau appeared in the magazine. She described Martineau's success as "an astonishing triumph of natural capacity over the disabilities of her position, her health and her sex." (116)

In the Easter 1933 Lady Rhondda and Theodora went on a cruise to Madeira, Tenerife, Morocco and Gibraltar. Before the cruise Theodora had admitted to herself that she was attracted by the young Theresa J. Dillon. However, she noted that "at my time of life sexual adventures are not likely to be much in my way" and reasoned that "the Platonic ideal of controlled impulse is probably the ideal for friendship". (117)

The following autumn they went on another cruise. They became intimate and on their return, to live together in Rhondda's Hampstead flat. (118) Four years later they moved into the newly built Churt Halewell near Shere in Surrey. When she first saw the house Bosanquet described the house as "A delight. A pleasance. It will give unmixed satisfaction." Built of local sandstone with "a lovely garden and hidden walkways, it was surrounded by woods and offered privacy, comfort and space." Lady Rhondda also added a swiming pool. (119)

In 1937 Theodora Bosanquet became literary editor of Time and Tide. It was argued by C. V. Wedgwood that In this role she "encouraged writers and hosted luncheons at Gourmets Restaurant." (120) Lady Rhondd told Winifred Holtby that Bosanquet "is very fine I think in many ways - finer than she gets the credit for being." (121) Freya Stark commented that Bosanquet was both "fastidious and amusing" and that Lady Rhondda and her "go very well together". (122)

Later Years

Lady Rhondda did not allow politics to get in the way of good writing and contributors to the magazine included D. H. Lawrence, Rebecca West, Vera Brittain, Winifred Holtby, Virginia Woolf, Crystal Eastman, Charlotte Haldane, Storm Jameson, Nancy Astor, Margaret Bondfield, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Charlotte Despard, Emmeline Pankhurst, Eleanor Rathbone, Olive Schreiner, Helena Swanwick, Margaret Winteringham, Ellen Wilkinson, Ethel Smyth, Emma Goldman, George Bernard Shaw, Ernst Toller, Robert Graves and George Orwell. However, it never sold well and it is estimated that during the thirty-eight years she lost over £500,000 on the magazine. The last edition of the magazine was published on 15th February 1958. (123)

Margaret Haig Thomas, Lady Rhondda, died in the Westminster Hospital on 20th July 1958.

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

Until I was thirteen I learnt what trifles I did learn from governesses, first French and later German, but at thirteen. I was sent to Notting Hill High School. It was my father who wanted this. I suppose he realised that there was no serious connection between the governesses and education.

The German governess, however, remained, and conducted me every morning in a four-wheeler from our flat in Westminster to Notting Hill. When school was over she called for me and walked me back through the parks.

Two years later I went to St. Leonards School, St. Andrews. This was at my own wish. I had discovered that at St. Leonards girls were allowed to go out for walks by themselves without attendant mistresses. This spelt freedom, and it was for freedom that I thirsted. I went to my father and told him what I wanted to do. Would he help? He was at first a shade doubtful. He knew little of girls' boarding schools, but his sister Mary had been to one, and he thought she had learnt to be silly there. The girls, he understood, used to flirt with the boys at an army crammer's next door.

(2) Margaret Haig Thomas was very close to her father, David Alfred Thomas. She wrote about it in her autobiography, This Was My World (1933)

I must have been about eleven or twelve when he first "talked business" to me: that is, poured out a stream of description of some deal he was engaged on at the time, without any explanations - he hated explaining anything; it bored him. He walked up and down the room as he talked, turning his coins over in his pocket, and I, seated in the big armchair, listened palpitating with pride at being treated in so grown-up a fashion, but terrified of saying the wrong thing, and so showing that I was only understanding about one quarter of what he was saying, which I well knew would have instantly stopped the flood. On that occasion my mother was up in town ill, and there was no one else at home for him to talk to. He always talked business at home a great deal; he would retail every evening all that had interested him in the day's events.

(3) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

During the formative period of childhood and adolescence and and as a young woman one was treated quite differently, in a thousand different ways, from the way in which a boy would have been. One was more protected, less was expected of one in very many directions (although more, of course, in others). A girl in innumerable subtle indirect ways is taught to mistrust herself. Ambition is held up to her as a vice - to a boy it is held up as a virtue. She is taught docility, modesty and diffidence. Docility and diffidence are of uncommonly little use in the business or professional world. A girl, after all, is all the while being prepared for her own special profession; and the profession of a wife or of a daughter at home is best and most successfully carried out by those who are prepared to defer to the judgment of others before their own.

(4) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

I was determined to join the Pankhursts' organisation, the Women's Social and Political Union, but was held up in this resolve for three months by the fact that my father, who had considerable foresight and realised pretty well what joining that body was likely to mean, was inclined to be opposed to the idea. However, I finally decided that he could be no judge of a matter which concerned one primarily as a woman. Prid meanwhile had, travelling by a slightly different road, arrived at the same conclusion. She and I met one autumn day in London, and, full of excitement, went off together to Clement's Inn and joined.

One of the first effects that joining the militant movement had on me, as perhaps on the majority of those of my generation who went into it, was that it forced me to educate myself. I read to begin with, of course, the whole literature of feminism: leaflets, pamphlets, books in favour and books against. Of books that mattered dealing directly with feminism there were curiously few. Only three now stay in my mind: John Stuart Mill's Subjection of Women, Olive Schreiner's Woman and Labour, Cicely Hamilton's Marriage as a Trade; and perhaps one should add a fourth, Shaw's Quintessence of Ibsenism. Of course, there were stray passages in others; one or two of Israel Zangwill's Essays, for example, I find unforgettable to this day.

Of the quantities of books on politics, economics, finance, the working of the Exchanges, sociology, anthropology and psychology which I read during the first few happy years of that new revelation, some few still remain fresh in my mind. I can still, for example, vividly remember reading Havelock Ellis's Psychology of Sex. It was the first thing of its kind I had found. Though I was far from accepting it all, it opened up a whole new world of thought to me. I discussed it at some length with my father, and he, much interested, went off to buy the set of volumes for himself; but in those days one could not walk into a shop and buy The Psychology of Sex; one had to produce some kind of signed certificate from a doctor or lawyer to the effect that one was a suitable person to read it. To his surprise he could not at first obtain it. I still remember his amused indignation that he was refused a book which his own daughter had already read. But the fact was that the Cavendish Bentinck Library, to which I, in common with many others, owe a deep debt of gratitude, was at that time supplying all the young women in the suffrage movement with the books they could not procure in the ordinary way.

(5) In May 1915, Margaret Haig Thomas was returning from the United States on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed by a German submarine. She wrote about the experience in her autobiography, This Was My World (1933)

It became impossible to lower any more from our side owing to the list on the ship. No one else except that white-faced stream seemed to lose control. A number of people were moving about the deck, gently and vaguely. They reminded one of a swarm of bees who do not know where the queen has gone.

I unhooked my skirt so that it should come straight off and not impede me in the water. The list on the ship soon got worse again, and, indeed, became very bad. Presently the doctor said he thought we had better jump into the sea. I followed him, feeling frightened at the idea of jumping so far (it was, I believe, some sixty feet normally from "A" deck to the sea), and telling myself how ridiculous I was to have physical fear of the jump when we stood in such grave danger as we did. I think others must have had the same fear, for a little crowd stood hesitating on the brink and kept me back. "And then, suddenly, I saw that the water had come over on to the deck. We were not, as I had thought, sixty feet above the sea; we were already under the sea. I saw the water green just about up to my knees. I do not remember its coming up further; that must all have happened in a second. The ship sank and I was sucked right down with her.

The next thing I can remember was being deep down under the water. It was very dark, nearly black. I fought to come up. I was terrified of being caught on some part of the ship and kept down. That was the worst moment of terror, the only moment of acute terror, that I knew. My wrist did catch on a rope. I was scarcely aware of it at the time, but I have the mark on me to this day. At first I swallowed a lot of water; then I remembered that I had read that one should not swallow water, so I shut my mouth. Something bothered me in my right hand and prevented me striking out with it; I discovered that it was the lifebelt I had been holding for my father. As I reached the surface I grasped a little bit of board, quite thin, a few inches wide and perhaps two or three feet long. I thought this was keeping me afloat. I was wrong. My most excellent lifebelt was doing that. But everything that happened after I had been submerged was a little misty and vague; I was slightly stupefied from then on.

When I came to the surface I found that I formed part of a large, round, floating island composed of people and debris of all sorts, lying so close together that at first there was not very much water noticeable in between. People, boats, hencoops, chairs, rafts, boards and goodness knows what besides, all floating cheek by jowl. A man with a white face and yellow moustache came and held on to the other end of my board. I did not quite like it, for I felt it was not large enough for two, but I did not feel justified in objecting. Every now and again he would try and move round towards my end of the board. This frightened me; I scarcely knew why at the time (I was probably quite right to be frightened; it is likely enough that he wanted to hold on to me). I summoned up my strength - to speak was an effort - and told him to go back to his own end, so that we might keep the board properly balanced. He said nothing and just meekly went back. After a while I noticed that he had disappeared.

(6) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

Various small acts of militancy had been performed by our local branch, but we had not done anything very spectacular or been particularly successful. I decided that we had better try burning letters. As it happened, burning letters was the one piece of militancy of which, when it was first adopted, I had disapproved. I could not bear to think of people expecting letters and not getting them. I had come round to it very reluctantly, partly on "the end justifies the means" principle; but chiefly on the ground that everyone knew we were doing it and therefore knew that they ran the risk of not getting their letters; and that it was up to the public to stop us if they really objected, by forcing the Government to give us the vote.

However, when it came to the point it was obvious that in the case of a local district, at some distance from head-quarters, burning the contents of pillar boxes had, tactically, much to recommend it. Acts which shall damage property without risking life and which shall not involve the certain risk of being caught are, as anyone who has tried them knows, very much more difficult to perform than they sound.

Setting fire to letters in pillar boxes was amongst the easiest of the things we could find to do. So one summer's day I went off to Clement's Inn to get the necessary ingredients. I was given, packed in rather a flimsy covered basket, twelve long glass tubes, six of which contained one kind of material and the other six another. So long as they were separate all was well, but if one smashed one tube of each material and mixed the contents together, they broke, so it was explained to me, after a minute or two into flames. I carried the basket home close beside me on the seat in a crowded third-class railway carriage, and the lady next door to me leant her elbow from time to time upon it. I reflected that if she knew as much as I did about the contents she would not do that.

Having got the stuff home, I buried it in the vegetable garden under the black-currant bushes, and a week or so later, dug it up and took it one day into the Newport Suffragette Shop to explain to the other members of committee what an easy business setting fire to pillar boxes would be for us all to practise in our spare moments.

(7) Margaret Haig Thomas, Time and Tide (14th May, 1920)

That the group behind this paper is composed entirely of women has already been frequently commented on. It would be possible to lay too much stress upon the fact. The binding link between these people is not primarily their common sex. On the other hand, this fact is not, without its significance. Amongst those to whom the need we have spoken of is apparent today are a very large number of women. Women have newly come into the larger world, and are indeed themselves to some extent answerable for that loosening of party and sectarian ties which is so marked a feature of the present day. It is therefore natural that just now many of them should tend to be especially conscious of the need for an independent press, owing allegiance to no sect or party. The war was responsible for breaking down the barriers which kept each individual or group of individuals in a watertight compartment. The past five years have taught the importance of that wider view which sees the part in relation to the whole.

There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women - the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings. It must be admitted that the press of today, although with self-conscious, painstaking care it now inserts "and women" every time it chances to use the word "men" scarcely succeeds in attaining to such an ideal.

(8) Charlotte Haldane, Daily Express (19th May, 1922)

Lady Rhondda is the most remarkable businesswoman in the world. She is a most feminine creature of the greatest outward simplicity, whose soft grey eyes and light brown hair were matched in their gentleness only by the charm of her low, even, and tranquil voice.

If she wins her battle for the right to take her seat in the House of Lords she will have created another record, and added another victory to her championship of women's equality.

(9) Crystal Eastman, Christian Science Monitor (8th March, 1922)

The question "Is the Leisured Woman a Menace to Civilization?" the topic of the recent debate at Kingsway Hall between Viscountess Rhondda and G. K. Chesterton, with Bernard Shaw in the chair, had almost a Bolshevist flavor. Yet Lady Rhondda, who maintained the affirmative is a wealthy woman, owner of vast coal properties, with no Socialistic tendencies whatever; she is a peeress in her own right, only daughter of David Alfred Thomas, later Viscount Rhondda, who was given a peerage in recognition of his services as food controller during the war.

Viscount Rhondda left to his daughter not only his title but full possession, direction and control of his extensive properties, exactly as though she had been a son. She inherited not only his money but his directorships, his active place in the financial world. And she made a gallant and distinguished fight to take his seat in the House of Lords. Twice, however, it has been decided, after a long legal battle with counsel of the very highest rank on both sides, that no woman may sit in that august body.

"Lady Rhondda is the terror of the House of Lords," said Bernard Shaw, in introducing her on this occasion. "She is a peeress in her own right. She is also an extremely capable woman of business, and the House of Lords has risen up and said, 'If Lady Rhondda comes in here, we go away!' They feel there would be such a show-up of the general business ignorance and imbecility of the malesex as never was before."

No, it was not radicalism that led Lady Rhondda to attack the idle women of her own class, it was feminism. She is a feminist, heart and soul, consistent to the last degree. She owns and edits a weekly journal. Time and Tide, which in style and matter and in general interest holds its own with the other serious English weeklies. It is in no sense a propaganda organ, and yet it never misses a chance to set forth, explain and uphold the feminist position on every issue which arises.

(10) Margaret Haig Thomas, letter to Helen Archdale (10th November, 1926)

I don't know whether you ever ask yourself why we live together; if you ever go back to the time when we first came together. We began it for the only reason that can make living together possible, because we were very fond of one another. I have paid heavily for believing that your love, that seemed a real thing, was real - when in fact it can only have been a passing surface passion, much as I've seen you several times. I gave all I had to give and for years now I have been struggling not to see, what you were making only abundantly clear, that the only value I had in your eyes was as some one who could give the children treats. And even though that was my own role of value you shut me always and persistently outside the family circle and taught the children to do the same - one was allowed as a hanger-on - because one was useful - but no more. When I tried to tell you I cared, you sneered. I imagine you despised me because I was too ready to give - but you see you had been ready enough at first and I couldn't believe for a long while that you had changed.... I imagine the end cannot be very far off now. To live together is possible only when people love each other. These last few weeks with the queer calm we are keeping on the surface, can't last.