Henry Luce

Henry Luce, the son of Henry Winters Luce, a Presbyterian missionary, was born in Tengchow, China, on 3rd April, 1898. In 1905 the mission asked Luce to raise funds in America. While in Chicago the family met Nancy Fowler McCormick, the widow of Cyrus McCormick. She was so impressed by the seven year old Henry that she asked for permission to raise him in America. They refused the offer but she insisted that she paid for the boy's education.

While in America he was taken ill. The doctors decided to take Luce's tonsils out. The anesthetic wore off too soon and Luce recovered consciousness during the operation. After this he developed a stammer. According to Isaiah Wilner: "Luce spoke in violent bursts punctuated by long, awkward silences. Often it seemed as if he was fighting to control his tongue or to keep up with his racing thoughts. At times the stammer completely defaced Luce's speech... Embarrassed by his problem. Luce began to turn inward. He developed a prickly stridency, an urge to win at all costs, and at times a rough male hostility."

Luce returned to China in 1907. He attended the China Inland Mission School. He hated the school and told his parents he was desperately lonely: "It sort of seems to hang on not in spells of homesickness but a hanging torture... I well sympathize with prisoners wishing to commit suicide now." During this period he became very religious. In 1909 he wrote of God: "I seem more on the same pedestal with him, more at homw, more as one of his chosen and I feel certain that he is at my side."

Luce eventually became friends with a British boy named Sydney Cecil-Smith. The two boys decided to start up their own newspaper. He wrote to his parents that "I am the Editor in Chief". Luce wrote the editorial and the lead article and the newspaper included school news, fiction and poetry.

In October 1911 the political situation became difficult in China and fearing revolution, Henry Winters Luce sent his son to school in St Albans in England. He also spent time in Switzerland, where he studied French. In 1913 he was sent to Hotchkiss School in Connecticut. While at the school he met Briton Hadden, another young man who was very interested in becoming a journalist. Stephen Shadegg later recalled: "Many of Luce's schoolmates thought of him as a bookish square; to the fun lovers he was a wet blanket who seldom went to a party or dated a girl. With the athletic students he wasn't popular - he had no aptitude for sports."

Soon after arriving the Hotchkiss Record , announced a new competition for sophomores. The student who showed the most "natural ability" would be taken onto the board of the newspaper. Hadden came first, beating Luce into second place. Luce wrote to his father: "I am second though quite far behind the first fellow (Hadden) and while I am not satisfied with second place, yet I think it was worthwhile."

In his senior year, Hadden became editor of the Hotchkiss Record . Luce now decided to concentrate on the Hotchkiss Literary Monthly . A fellow worker on the magazine Culbreth Sudler, later recalled: "He (Luce) had a kind of terrifying egotism. Everything was up there in his head. His personality, his manner, didn't matter. Nothing mattered except the idea."

When Nancy Fowler McCormick discovered that Luce wanted to become a writer, she introduced him to her friend, the successful author, Lyman Abbott. He advised Luce to write as much as he could for the student newspaper. Hadden provided him with help by appointing Luce as assistant managing editor. He also edited the Hotchkiss Literary Monthly. He shocked its readers by transforming the "offbeat little monthly into a mainstream magazines of campus life."

In 1916 Luce and Briton Hadden both went to Yale University and found themselves in competition to have their work published in the Yale Daily News. This involved what was known as "heeling rituals". Between October and March, the young students (heelers) wrote articles, sold advertising in the newspaper and performed various tasks for the editorial board. The editors awarded a certain number of points for each task. At the end of the competition, the top four heelers were appointed to the staff of the newspaper. Alger Shelden, the son of a millionaire attempted to buy his way to victor. However, he could only finish second to Hadden, who won with more points than any heeler in history. Luce finished in fourth place. He wrote to his father: "I have come to Rome and succeeded in the Roman Games."

Shelden invited Hadden, Luce and the fourth successful heeler, Thayer Hobson, to spend Easter at the family estate at Grosse Pointe near Detroit. Hadden wrote to his mother that he had accepted the invitation because he wanted to become better acquainted with Shelden, Hobson and Luce "whom I will have to work with more or less during the next few years". Luce told his father that he was excited by the visit as Shelden's father was a close friend of Theodore Roosevelt. While they were staying at the Shelden estate, President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany.

When they arrived back at Yale University Hadden and Luce launched a campaign in the Yale Daily News to support the war effort by encouraging the wealthy students to purchase war bonds. They also encouraged young men to join the armed forces and by the autumn of 1917 a third of the students at Yale had left to take part in the First World War. This included John Elliot Wooley, the chairman of the newspaper. Luce and Hadden both put their name forward for the top job. Hadden was elected to the post and Luce wrote to his parents: "Briton Hadden is chairman of the News, and thus my fondest college ambition is unachieved."

Hadden used his new position to call for Yale to offer more classes in subjects like semaphore signaling and drill. This campaign was successful and according to one observer, "for the rest of the war the school became a military academy in all but name". Luce was also a strong supporter of the war effort. He accused his English professor of being a pacifist and suggested that Yale should ban all student groups that could not be classified as "war industries". Hadden and Luce would often print fake letters in order to create debates about controversial subjects. This strategy increased sales of the newspaper.

The following year Hadden was elected chairman of the Yale Daily News for a second time and Luce won election as the managing director. During this period the two young men became very close. Luce later commented: "Somehow, despite greatest differences in temperaments and even in interests, somehow we had to work together. At that point everything we had belonged to each other."

Luce and Hadden both wanted to become members of the Skull and Bones group. Only fifteen students were allowed to join each year. They achieved the honour in 1919. Other members of this secret society include William Howard Taft, Henry L. Stimson, William Averell Harriman, Clarence Douglas Dillon, Frederick Trubee Davison, James Jesus Angleton, William F. Buckley, McGeorge Bundy, Robert A. Lovett, Potter Stewart, Lewis Lapham, George H. W. Bush and his son, George W. Bush.

In 1920 Luce, while on holiday in Rome, met Lila Ross Hotz, who came from a very wealthy family in Chicago. They got on well together. Stephen Shadegg has argued: "To compensate for the stammer which still embarrassed him at time, he had learned to speak slowly, deliberately, which often seemed pontifical to others. The slim Lila was quite different. She was voluble, impulsive and extravagant. Luce, who had little time for girls in college, fell in love." The following Lila wrote to her mother: "His name is Luce - don't know his first name, or where his home is - or anything. Yet I do know what he thinks about many things! Agreed by us all to be the best looking man ever - which does count!... He was quite the most heavenly thing to talk to."

Luce returned to the United States and decided to start a career in business. Nancy Fowler McCormick arranged for him to have an interview with the International Harvester Company. McCormick told the general manager of the company, Alexander Legge, to find him a good job in the organisation. Legge said to Luce: "If Mrs. McCormick wants us to do it, we'll do it. But now, Luce, do you want us to do it? If we take you on, you know, we have to fire somebody else." Given this option, Luce declined the offer of a job with a company.

Luce told Mrs. McCormick he really wanted to become a journalist. She introduced him to her good friend, Victor Lawson, owned the Chicago Daily News. He arranged for him to become an assistant to his top reporter, Ben Hecht. He was not impressed with the young man's abilities and after ten days he recommended that Luce should be fired. Henry Justin Smith, who did not want to upset Lawson, moved him to the city room. He was found to be unsatisfactory in this department and in November 1921 he was sacked by Smith.

The following month his friend, Briton Hadden, found him a job working on The Baltimore News-Post. They spent much of their spare-time discussing the possibility of starting their own news magazine. Hadden argued that most people in the United States were fairly ignorant of what was going on in the world. According to Hadden, the main problem was not a lack of information, but too much. He pointed out there were over 2,000 daily newspapers, 159 magazines and nearly 500 radio stations in America. The two men objected to the emphasis placed on entertainment by these various media organisations. The situation became worse when in 1919 a Chicago publisher, Joseph Medill Patterson, moved to New York City and launched his tabloid newspaper, the Daily News. Making good use of photographs, the newspaper concentrated on murder stories and celebrity scandals.

Luce and Hadden intended to change this trend by producing a magazine that dealt with serious news. Luce wrote to his father: "True, we are not going out like Crusaders to propagate any great truths. But we are proposing to inform people - to inform many people who would not otherwise be informed; and to inform all people in a manner in which they have never been informed before."

Over the next few months they began working on their proposed news magazine. Every day they cut-up the New York Times and separated the articles into topics. At the end of the week, they extracted the main events and rewrote the stories in their own words. Luce and Hadden showed these mock-ups to their former English professors, Henry Seidal Canby and John Milton Berdan. Canby thought the writing was "positively atrocious" and "telegraphic". Berdan was more sympathetic and accepted that the style was essential if they were to compete with movies, radio shows and billboards. Despite his criticism of the writing, Canby advised the men to continue with the project.

Luce and Hadden resigned their jobs at the Baltimore News-Post and moved back to New York City where they moved in with their parents. They also recruited their friend, Culbreth Sudler, as their business manager. They drew up a prospectus that they could show prospective investors. It included the following: "Time is a weekly news magazine, aimed to serve the modern necessity of keeping people informed, created on a new principle of complete organization. Time is interested - not in how much it includes between its cover - but in how much it gets off its pages into the minds of it's readers." It added that the magazine "would entertain as well as edify" and argued that they would tell the news through the personalities who made the headlines.

A friend of Luce's father introduced them to W. H. Eaton, the publisher of World's Work. He later recalled: "I spent a full afternoon with those fellows going over their first dummy, discussing their editorial philosophy. They certainly were intense about the whole thing, and Hadden seemed to be driving every minute of the time. But it didn't have a professional look to me. I told them I didn't think they'd have a Chinaman's chance." Eaton was so convinced they posed no threat to his magazine, he gave them a list of several thousand of his own subscribers. He also helped them draft a subscription letter that was mailed to a 100,000 people. Of these, over 6,000 people requested trial subscriptions.

Luce and Briton Hadden also had a meeting with John Wesley Hanes, an experienced figure on Wall Street. He told them that it was foolhardy to compete with the highly successful Literary Digest. However, he was especially impressed with Hadden: "Hadden was damned convincing... Luce was there, too. They made a good team. But Luce wasn't much of a talker. He thinks faster than he can talk, you know, and sometimes it gets garbled up. But all the time, Hadden would be in there, selling, selling. He just had what he takes. He was intelligent, he was enthusiastic, he was willing to work and work hard. He was the whole ball of wax rolled into one." Culbreth Sudler agreed that Hadden was very impressive in his dealings with potential investors. He later recalled: "Hadden was interested in everybody. His mind was tireless, and he had an almost unparalleled drive coupled with a strong personal discipline."

Hanes gave them important advice on how to raise money from investors while retaining control of the company. He told them to create two kinds of stock. Preferred stock would pay dividends to investors sooner, but only the common stock would carry the right to vote on company affairs. Under this plan, Hadden and Luce would each keep 2,775 shares - a total of 55.5%, giving them control of the company.

Hadden and Luce used their contacts through the Skull and Bones secret society. A fellow member, Henry Pomeroy Davison, Jr., persuaded his father, Henry Pomeroy Davison, a senior partner at J. P. Morgan, the most powerful commercial bank in the United States at the time, to invest money in the magazine. Davison introduced Luce to fellow partner Dwight Morrow, who also bought stock in the company. Another member, David Ingalls, had married Louise Harkness, the daughter of William L. Harkness, a leading figure in Standard Oil. He had recently died and left $53,439,437 to his family. Louise used some of this money to invest in the magazine. By the summer of 1922 Hadden and Luce had raised $85,675 from sixty-nine friends and acquaintances.

Briton Hadden, who was appointed editor of Time Magazine, now began to acquire his staff. Thomas J. C. Martyn, a former pilot in the Royal Air Force during the First World War, who had lost his leg in an aircraft accident, was given the job of Foreign News editor. He had little experience in journalism but Martyn, who was fluent in French and German, seemed to know a great deal about European politics. Another successful appointment was John Martin, who specialized in writing humorous stories for the magazine. Roy Edward Larsen, was appointed as circulation manager. He had just left Harvard University, where he was business manager of the college literary magazine, The Advocate. Luce had been impressed by the fact that he had been the first person in history to turn it into a profit-making venture.

The first edition of Time Magazine was published on 3rd March, 1923. Only 9,000 copies were sold, a third of what it would take to break even in the first year of business. In an attempt to increase sales, Hadden employed young women to ask for the magazine at news-stands. Their reply was that they had never heard of it. After a few women had requested a copy of the magazine, Hadden arrived and by that time they were in the right mood to take a couple of copies.

According to Isaiah Wilner, the author of The Man Time Forgot (2006): "Gradually Time gained a following among the young and modern set. College students kept the magazine on the coffee tables, circled favorite phrases or surprising facts, and quoted them to friends. A single issue would make its way through several sets of hands." After six months the magazine was selling 19,000 copies a week. By March 1925, Time Magazine had a paid circulation of 70,000 subscribers. In its second year, the magazine made a profit of $674.15.

Despite an increase in revenue, Henry Luce still had trouble paying suppliers. Roy Edward Larsen was asked to come up with a way of finding more income from advertising in the magazine. Hadden suggested the idea of increasing the price of smaller adverts and offering a discount for buying in bulk. This method not only improved revenue but eventually became the industry standard for selling advertising. Larsen devised several different subscription offers. This included paying the cost of postage. The company also supplied a self-addressed and stamped postcard in their mailing.

Although Time Magazine claimed it provided an objective view of the world, its editor, Hadden, always sided with the underdog. He ran several stories on the lynching of black men in the Deep South. This provoked complaints from readers who held conservative views on politics. One reader, Barlow Henderson of South Carolina, accused the magazine of a "flagrant affront to the feelings of our people". His main objection was to the policy of giving black people the respectful title of "Mr."

Briton Hadden hired a team of four young women to do research. They searched through newspapers and books in search of revealing details that they would then pass onto the journalists. The women also had the job of checking the facts of the articles before they were published in the magazine. The researchers were paid half the wages of the journalists on the magazine and Hadden was therefore able to cut the size of the payroll.

With the growing success of Time Magazine, the parents of Lila Ross Hotz, agreed that Luce could marry their daughter. The couple married in December 1923. Henry Winters Luce assisted at the church service. Afterwards they had a separate Skull and Bones wedding. The New York Evening Journal, described Hotz as "a member of the swagger younger set in the Windy City".

Time Magazine targeted the upwardly mobile. It was particularly successful with the younger set of upper-class readers. Hadden wrote that he was not interested in obtaining those readers who read tabloid newspapers. He described them as "gum-chewers, shop girls, taxi drivers, street sheiks, and bummers".

Briton Hadden, the editor of the magazine, created a new style of writing. He was a savage editor who stripped the sentence down, cut extraneous clauses, and used only active verbs. He also removed inconclusive words words like "alleged" and "reportedly". Hadden also liked using the odd obscure word. The author of The Man Time Forgot (2006) has pointed out: "By sprinkling the magazine with a few difficult words, Hadden subtly flattered his readers and invited them to play an ongoing game. Those with large vocabularies could pat themselves on the back, while the rest guffawed at Time's bright boys and looked the word up."

The editor of Time Magazine was also interested in creating new words. For example, while at Hotchkiss School he described boys who had few friends as being "social light". In his magazine he began using the word "socialite" to describe someone who attempted to be prominent in fashionable society. Hadden wanted a new word for opinion makers. As they thought themselves as wise, he called them by the name of his old Yale prankster group: "pundit". Another word brought into general use was "kudos", the Greek word for magical glory. Henry Luce also developed new words. The most famous of these was "tycoon" to describe successful and powerful businessman. The word was based on "taikun", a Japanese term to describe a general who controlled the country in the name of the emperor.

Briton Hadden encouraged his writers to use witty epithets to convey the character and appearance of public figures. Grigory Zinoviev was condemned as the "bomb boy of Bolshevism" and Upton Sinclair was called a "socialist-sophist". Winston Churchill was described as being "ruddy as a round full moon". Benito Mussolini was attacked on a regular basis. John Martin commented that when public figures came under attack from Hadden, it was like being "undressed in Macy's window".

Articles in Time Magazine were very different from those found in other newspapers and journals. Isaiah Wilner has pointed out: "Having invented a new writing style that made each sentence entertaining and easy to grasp. Hadden and his writers began to toy with the structure of the entire story. Most newspaper writers tried to tell everything in the first one or two paragraphs. By printing the most important facts first, they destroyed the natural narrative of news. Hadden trained his writers to act as if they were novelist. He viewed the whole story, including the headline and caption, as an information package."

Henry Luce's secretary, Katherine Abrams, commented: Luce is the smartest man I ever knew, but Hadden had the real editorial genius... He was warm and he was human and he had what Luce lacks, an instinct for people." Culbreth Sudler added: "Briton Hadden was Timestyle. It was Timestyle that made Time popular nationwide, and therefore it was Hadden who made Time a success." By 1927 was selling over 175,000 copies a week.

Briton Hadden commented on his relationship with Luce to a friend: "It's like a race. Luce is the best competition I ever had. No matter how hard I run, Luce is always there." Luce was told about this and later he recalled: "If anyone else had said that, I might well have resented the implication that the best I could do was to keep up with him. Coming from Hadden, I regarded it, and still regard it, as the highest compliment I have ever received." Polly Groves, who worked at Time Magazine, remarked: "Everyone who knew Briton Hadden loved him. You couldn't love Henry Luce. You admired him but could not love him."

Isaiah Wilner has argued: "Luce called Hadden an original and was deeply influenced by his ideas. Throughout their many battles, whether for the editorship of the school paper or for creative control of Time, it was Hadden who won. Luce, who couldn't stand to lose, had been forced to content himself with second place for more than a decade. He had worked as Hadden's deputy in both prep school and college... Luce had continued to live in Hadden's shadow ever since."

In March, 1925, Briton Hadden went on a long vacation. The following month Luce discovered that Time Incorporated had lost $1,958.84 over the previous four months. He decided that he could save a considerable sum of money by relocating to Cleveland. John Penton, claimed he could save Luce $20,000 a year by printing the magazine in the city. Luce signed the contract without telling Hadden. When he arrived home from holiday Hadden had a terrible row with Luce. According to Hadden's friends, Luce's action struck a severe blow to their partnership.

Time Magazine moved to Cleveland in August, 1925. The advertising staff remained behind in New York City. Most of the journalists, researchers and office staff refused to relocate. This was partly because Luce refused to pay for their moving expenses. Instead, he sacked the entire staff but offered to reappoint them if they applied for jobs in Cleveland. Thomas J. C. Martyn was furious about the way he was treated and refused to move.

Luce rented a house near Shaker Heights. Luce told Lila Ross Hotz: "I think all my efforts are now centered around a vision of you and me having a good time for a mighty long time... Of course one has visions of more... One imagines oneself famous. One even imagines oneself powerful." Lila became involved in the social scene. After one successful party she told her mother: "Harry says I rose to the occasion like a cake of yeast in the oven."

In December, 1925, Roy Edward Larsen organised a new subscription campaign. It was a great success and the magazine's circulation increased to 107,000. However, that year, the company lost $24,000, but this was largely due to the cost of the move to Cleveland. Luce claimed the future looked bright as the relocation had made the magazine more popular outside of New York City.

Dorothy McDowell, who worked with Luce at Time Magazine, commented: "Luce was the best pencil editor I ever saw... I never saw a man who could so make something out of a disjointed, poorly organized thing... He was not as good an idea man as Briton Hadden, but he sure could operate on a manuscript."

In 1926 circulation reached 111,000. Advertising revenues rose to $240,000 and the company made a profit of $10,000. The main concern was that sales from news-stands remained poor. It was decided to carry out a study into the situation. One newsdealer commented: "What you need on the cover is pretty girls, babies, or red and yellow." Several people interviewed said that the black and white magazine cover was not appealing to the potential customers. On 3rd January, 1927, the magazine appeared with a red-bordered front cover. Atwater Kent also paid $1,400 for the back-cover that carried a bold yellow advertisement for the company.

At the beginning of 1927, Hadden agreed to switch jobs with Luce. Hadden now began exploring ways of increasing advertising revenue. He carried out a survey of the magazine's readership. He then published a booklet that was distributed to advertisers. It claimed that the magazine was read by people who were "wealthy, powerful, informed and energetic". He was "an informed consumer who spent his money freely and paid attention to what companies said to him." That year advertising revenues climbed to nearly $415,000.

Luce also made changes as editor. Laird Goldsborough was Foreign News editor of the magazine. Goldsborough held extreme right-wing opinions but this was kept under control by Briton Hadden, who instructed his journalists to tell both sides of an event. The two men disagreed about the merits of Benito Mussolini. Hadden was a strong supporter of democracy and severely attacked the rule of Mussolini, who he described as a "tin-pot dictator". Goldsborough on the other hand praised Mussolini as a bold leader.

Goldsborough found his new editor as much more sympathetic to his right-wing views. Isaiah Wilner has pointed out: "No sooner had Luce taken the editor's seat than he began to twist and distort the news. Time's emerging bias first grew evident in Foreign News. Laird Goldsborough quickly impressed Luce with his writing ability and knowledge of foreign events." George Seldes has argued that Luce "permitted an outright pro-fascist, Laird Goldsborough, to slant and pervert the news every week."

In 1928 the two men argued about business matters. Henry Luce was keen to publish a second magazine that he wanted to call Fortune. Hadden was opposed to the idea of publishing a journal devoted to promoting the capitalist system. He considered the "business world to be vapid and morally bankrupt". Together, Hadden and Luce owned more than half of the voting stock and were able to retain control of the company. However, Luce was unable to publish a new magazine without the agreement of his partner.

In December 1928 Briton Hadden became so ill he was unable to go into the office. Doctors diagnosed him with an infection of streptococcus. Hadden believed he had contracted the illness by picking up a wandering tomcat and taking it home to feed it. The ungrateful cat attacked and scratched Hadden. Another possibility was that he had been infected when he had a tooth removed. The following month he was taken to Brooklyn Hospital. Doctors now feared that the bacteria had spread through his blood-stream to reach his heart.

Luce visited Hadden in hospital and tried to buy his shares in the company. Nurses reported that these conversations ended up in shouting matches. One nurse recalled that Hadden and Luce had yelled at each other so loudly that they could be heard from behind the closed door. Doctors believed that Hadden was wasting his precious energies in these arguments and it was partly responsible for his deteriorating condition.

On 28th January, 1929, Hadden contacted his lawyer, William J. Carr and asked him to draw up a new will. In the document, Hadden left his entire estate to his mother. However, he added that he forbade her from selling the stock in Time Incorporated for forty-nine years. His main objective was to prevent Luce from gaining control of the company they had founded together.

Henry Luce visited Hadden every day. He later recalled: "The last time or two that I was there, I guess I knew he was dying and maybe he did. It seemed to me that he knew and every now and again was wanting to say something, whatever it might be he wanted to say in the way of parting words or something. But he never did, so that there was never any open recognition between him and me that he was dying."

Briton Hadden died of heart failure on 27th February, 1929. The following week Hadden's name was removed from Time's masthead as the joint founder of the magazine. Luce also approached Hadden's mother about buying her stock in Time Incorporated. She refused but her other son, Crowell Hadden, accepted his offer to join the board of directors. Crowell agreed to try and persuade his mother to change her mind and in September 1929, she agreed to sell her stock to a syndicate under Luce's control for just over a million dollars. This gave him a controlling interest in the company.

Ralph Ingersoll was appointed as managing editor of Time Magazine in 1930. However, he grew critical of what Henry Luce was trying to do with the magazine: "Time's technique for handling news is so simple that it seems to have eluded several generations of critics and yet it is almost solely responsible for (A) Time's monumental commercial success and (B) Time's equally monumental failure in the fields of ethics, integrity, and responsibility. The problem Henry R. Luce and the late Briton Hadden tackled when they set out to invent their new kind of weekly news magazine was how to condense a week's news on all fronts: national, international, cultural, and business into a package of words that could be read cover to cover in a couple of hours."

Ingersoll went onto argue: "Controversial matters, such as political news, were handled by snipping quotes from both sides. But Luce and Hadden felt that this approach had limitations both as to the quantity of news it could handle and its readability... Luce and Hadden's solution was brilliant. Instead of digesting the news, they would rewrite it into short articles, each having its own literary form: a beginning, a middle, and an end, though not of course necessarily in that sequence. Thus they wrote their own literary license for a new kind of news writing that was not news writing at all but good old-fashioned, time-tested fiction writing."

Soon after Hadden's death, Luce began publishing Fortune. He also recruited Charles Douglas Jackson to help him run his growing media empire. Luce also produced The March of Time for radio (1931) and for the cinema (1935).

Henry Luce met Clare Boothe, the former managing editor of Vanity Fair, at a party in 1934. After talking for a couple of hours he told her: "I want to tell you that you are the great love of my life. And someday I am going to marry you." As Luce was already married she dismissed his suggestion and went on a long holiday to Europe. Luce did not accept this rejection and met up with her in Paris. As Stephen Shadegg has pointed out: "The courtship which followed was not a particularly romantic one. Harry Luce found it difficult to express his love in the conventional words of lovers. Like Clare, he always seemed on his guard, fearful lest someone might discover the soft, eager, not-at-all-cocksure human being behind his gruff exterior. But his devotion and determination were unmistakable. Intellectually he was the most interesting man Clare had ever encountered. She fell in love with him."

Wilfrid Sheed, the author of Clare Boothe Luce (1982) has argued: "The possibility that there was a powerful mutual attraction hedged with normal lunges and hesitations seemed ruled out by their importance and ambition. Yet Harry was in fact precisely her type: physically, he was close enough to other men whom I know she finds interesting (although Harry photographed grimly) to suggest that their romance wasn't just power calling to power... Nevertheless, it was important for her to make clear for the record that he pursued her, because the non-record, or myth, ran all the other way. To begin with, Harry was already married and had two sons, not to mention two edifying magazines. The Other Woman was always public enemy number one in those days, whatever the circumstances; but in this case, the circumstances were bad too. Harry looked like a pillar of rectitude (an old Presbyterian trick-his sexual rectitude was to prove just about the national average) and he also looked absentminded, as if a smart woman could steal him while he wasn't looking."

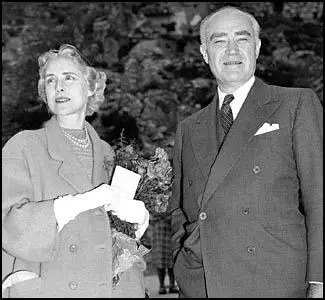

Luce divorced Lila Ross Hotz in September, 1935. According to Robert E. Herzstein, the author of Henry R.Luce: A Political Portrait of the Man Who Created the American Century (1994): "Lila was devastated when Luce confronted her with his intention to divorce her. But they maintained a closeness and were in constant contact, often discussing their children's education and careers, among other things.'' On 23rd November, 1935, Henry married Clare. The following year he began publishing the picture magazine, Life.

In 1936 Laird Goldsborough attempted to persuade Luce to take sides in the conflict in Spain. George Teeple Eggleston, who worked for the company at the time, has claimed that it was Goldsborough who persuaded Luce to support General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. According to Eggleston: "Time's conservative foreign news editor, Laird Goldsborough, promptly slanted all news stories in his department in favor of General Franco's rebel insurgents."

This approach was criticised by Archibald MacLeish, who worked on Fortune, another magazine owned by Luce, who "promptly bombarded Luce memos denouncing Franco's coalition of landowners, the Church, and the army". Goldsborough responded by arguing: "On the side of Franco are men of property, men of God, and men of the sword. What positions do you suppose these sorts of men occupy in the minds of 700,000 readers of Time? ... They resent communists, anarchists, and political gangsters - those so-called Spanish Republicans."

George Teeple Eggleston points out that Luce's wife, Clare Boothe Luce was on the side of the Republicans during the war: "Clare was violently anti-Franco and promptly contributed a thousand dollars to the pro-Communist Abraham Lincoln Brigade, which was gathering volunteers in New York City to fight against Franco in Spain."

Henry Luce purchased the humour magazine, Life, in 1936 so that he could acquire the rights to its name. Luce employed Ralph Ingersoll, one of his senior editors, to work on the project. Luce based his new magazine on similar picture magazines published in Germany during the 1920s. The weekly news magazine made full use of America's leading photojournalists such as Margaret Bourke-White, Carl Mydans, Grace Robertson, Constance Larrabee, Gordon Parks and Esther Bubley.

Luce predicted a circulation of 250,000. In order to cover the news-stands the first print order was for four hundred and forty-six thousands, but no one really expected to sell that many. According to Stephen Shadegg: "The public embraced Life with a passion. Some magazine stands began reserving all their favorite customers. Others just charged two or three times the published price of ten cents. At the end of three months the demand reached the one-million mark and the advertisers were getting four times the circulation they were paying for."

According to her friend, Wilfrid Sheed, Clare "had not lived together connubially" after Henry Luce resumed having affairs in the late 1930s. "Harry's famous conscience made it impossible for him to conduct two affairs at once, so as soon as someone, anyone, else came along, that was that. Whoever came along, I deduce, did so after about five years. If so, it suggests that their professional partnership got stronger as the chemistry got weaker."

In April 1939 Whittaker Chambers joined Time Magazine as a book and film reviewer. According to Jonathan P. Herzog, the author of The Spiritual-Industrial Complex: America's Religious Battle Against Communism in the Early Cold War (2011): "Chambers slowly climbed through the ranks of Time, Inc. and had entered the inner circle of advisers that Luce depended on for business and editorial decisions. In 1944 Luce made Chambers the head of Time's Foreign News. Predictably, Chambers moulded Time into an anti-Communist mouth-piece."

Warren Hinckle has argued: "Henry Luce believed that a morally slanted press was a responsible press... Life, the flagship picture book of the Luce fleet, afforded photojournalism some of its finest moments, while the text accompanying the pictures that were worth thousands of words was slanted with an ideological warp sufficient to stir Caxton in his grave." The cartoonist, Herbert Block, was equally critical: "Luce's unique contribution to American journalism... is that he placed into the hands of the people yesterday's newspaper and today's garbage homogenized into one neat package."

Marshall McLuhan was highly critical of Time Magazine: "The overwhelming fact about Time is its style. It has often been said that nobody could tell the truth in Time style. Time is a nursery book in which the reader is slapped and tickled alternately. It is full of predigested pap, spooned out with confidential nudges. The reader is never on his own for an instant, but, as though at his mother's knee, he is provided with the right emotions for everything he hears or sees as the pages turn... Totalitarianism engendered by the mass hypnosis of power, glitter, and the spectacle of regular ranks rather than insight or intelligibility is the object of all of Time's technical brilliance. Meanwhile, the editors of Time stand at mock attention in the reviewing stand, thumbing their noses at humanity."

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. Churchill realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain's ally. Randolph Churchill, on the morning of 18th May, 1940, claims that his father told him "I think I see my way through.... I mean we can beat them." When Randolph asked him how, he replied with great intensity: "I shall drag the United States in."

Churchill appointed William Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that Ernest Cuneo was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Dorothy Thompson, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Vincent Sheean, Eric Sevareid, Edmond Taylor, Rex Stout, Edgar Ansel Mowrer and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America". Cuneo also worked closely with editors and publishers who were supporters of American intervention into the Second World War. This included Henry Luce, Arthur Hays Sulzberger (New York Times), Helen Rogers Reid (New York Herald Tribune), Paul C. Patterson (Baltimore Sun), Marshall Field III (Chicago Sun) and Ralph Ingersoll (Picture Magazine).

In July, 1940, Henry Luce, Clare Boothe Luce, C. D. Jackson, Freda Kirchwey, Raymond Gram Swing, Robert Sherwood, John Gunther, Leonard Lyons, Ernest Angell and Carl Joachim Friedrich established the Council for Democracy. According to Kai Bird the organization "became an effective and highly visible counterweight to the isolation rhetoric" to America First Committee led by Charles Lindbergh and Robert E. Wood: "With financial support from Douglas and Luce, Jackson, a consummate propagandist, soon had a media operation going which was placing anti-Hitler editorials and articles in eleven hundred newspapers a week around the country."

During the 1940 Presidential Election the isolationist Chicago Tribune accused the Council for Democracy of being under the control of foreigners: "The sponsors of the so-called Council for Democracy... are attempting to force this country into a military adventure on the side of England." George Seldes also attacked the organization arguing that it was being mainly financed by Henry Luce.

However, according to The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45, a secret report written by leading operatives of the British Security Coordination (Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill), William Stephenson and BSC played an important role in the Council for Democracy: "William Stephenson decided to take action on his own initiative. He instructed the recently created SOE Division to declare a covert war against the mass of American groups which were organized throughout the country to spread isolationism and anti-British feeling. In the BSC office plans were drawn up and agents were instructed to put them into effect. It was agreed to seek out all existing pro-British interventionist organizations, to subsidize them where necessary and to assist them in every way possible. It was counter-propaganda in the strictest sense of the word. After many rapid conferences the agents went out into the field and began their work. Soon they were taking part in the activities of a great number of interventionist organizations, and were giving to many of them which had begun to flag and to lose interest in their purpose, new vitality and a new lease of life. The following is a list of some of the larger ones... The League of Human Rights, Freedom and Democracy... The American Labor Committee to Aid British Labor... The Ring of Freedom, an association led by the publicist Dorothy Thompson, the Council for Democracy; the American Defenders of Freedom, and other such societies were formed and supported to hold anti-isolationist meetings which branded all isolationists as Nazi-lovers."

Raymond Gram Swing defended the organisation by arguing: "As first conceived, the Council for Democracy was simply to be a co-ordinating body to pull together the work being done by a number of small organizations. But as it got under way, it became clear that a central organization supplanting many of the smaller ones would be more effective, and that is what the Council became.... Europe was at war; the United States was not. The war in Europe was one of the least complicated wars to understand; it was one of both conquest and ideology, waged by fascists. Democracy in Europe was in the most dire peril, which meant that in time it might well be in dire peril in the United States, too. The need for a Council dedicated to the preservation of democracy was incontestable. It had work to do; and within its means, as I now look back on it, it did that work. There was some indifference to democracy in the United States, as I assume there always has been. There was little outright fascism, but an inclination among not a few to be tolerant of it, which was the equivalent of being indifferent to the defense of democracy."

Luce was also one of the main funders with the British Security Coordination for the Fight of Freedom group. Other members included Allen W. Dulles, Joseph Alsop, Dean G. Acheson, Lewis William Douglas, and several journalists including Herbert Agar (Louisville Courier-Journal), Geoffrey Parsons (New York Herald Tribune) and Elmer Davis (CBS).

Ian Fleming, working for BSC's naval intelligence section, proposed that Luce should work for William Donovan as his Coordinator of Information. His recommendation was not accepted and the post went to Robert E. Sherwood. However, as Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has pointed out: "The British soon found themselves in conflict with Henry Luce. His global internationalist vision of the American Century and his ability to publicize that vision were very useful when the British were trying to involve the United States in international events. But they became a threat to the British vision of the postwar world after Pearl Harbor. By early 1943, Henry Luce was on the list of enemies who endangered the British Empire."

Luce was a supporter of the Republican Party. His wife, Clare Booth Luce, who shared his right-wing views, was elected to Congress in 1942 and represented Connecticut for the next four years. In her maiden speech she launched a savage attack on the internationalism of Vice President Henry A. Wallace. In February, 1945, he began a campaign for a permanent Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

David Halberstam has pointed out in The Powers That Be (1979): "Luce's politics hardened in the postwar years and Time had become increasingly Republican in its tone. He had been stunned by Truman's defeat of Dewey in 1948. Then in the fall of 1949 China had fallen, the Democratic administration had failed to save Chiang, and that was too much; Truman, and even more Acheson, would have to pay the price. Time was now committed and politicized, an almost totally partisan instrument. The smell of blood was in the air. There was a hunger now in Luce to put a Republican back in power. It was as if Luce, between elections, stood as the leader of the opposition, a kingmaker who had failed to produce a king. The fall of China and the rise of a post-war anti-Communist mood had produced the essential issue to use against the Democrats: softness on Communism."

Some left-wing figures believed they were persecuted by Time Magazine. Rockwell Kent commented: "Time is too strongly inclined to the ultra-right to be trustworthy in the forming of fair judgment in current political events. I feel itsstyle of writing to be objectionable and inclined to value smartness above truth." Howard Fast agreed: "Any reading of Time, even casual, will provide you with distortions and inaccuracies by the bushel."

Henry Luce used his media empire to get Dwight D. Eisenhower elected as president. In 1953 Eisenhower appointed Clare Booth Luce ambassador to Italy; the first American woman ambassador to a major country. Claudio Accogli, a Italian historian, argues that luce was heavily involved in covert anti-communist activities with local cia personnel. Larry Hancock adds: "With no-holds barred political activism and heavy spending (including the support of the SIFAR/Italian Army Secret Service), Luce and the CIA managed to block the probable takeover of the center-left governments, an alliance between Christian Democrats (DC) and the Socialist Democratic Party (PSI)."

In 1959 Eisenhower appointed her as ambassador to Brazil. The opposition to her appointment in Congress was led by Wayne Morse of Oregon. Clare commented Morse's actions were the result of him being "kicked in the head by a horse." This remark proved so controversial that Clare resigned the ambassadorship a few days later.

According to Carl Bernstein, Luce's close friend Charles Douglas Jackson, the publisher of Life Magazine, was "Henry Luce's personal emissary to the CIA". He also claimed that in the 1950s Jackson had arranged for CIA employees to travel with Time-Life credentials as cover. Drew Pearson supported this view: "Life magazine is always pulling chestnuts out of the fire for the CIA; and I recall that C. D. Jackson of the Life-Time empire was the man who arranged for the CIA to finance the Freedom Balloons. C. D. Jackson, Harold Stassen and the other boys who went with me to Germany spent money like money while I paid my own way. I always was suspicious that a lot of dough was coming from unexplained quarters and didn't learn until sometime later that the CIA was footing the bill."

Jonathan P. Herzog has argued that Luce was motivated by his religious faith: "While he counted anti-Communists like Mundt, Cardinal Spellman, and Chambers as allies, he viewed the Communist threat differently. In his view, it was a symptom and not a disease. Like his wife, Clare, he understood faith as a psychological imperative sought by all people. If religious faith waned, other dogmas would take its place. The success of Communism, then, was not attributable to its message but rather to the fact that it offered people the spiritual certainty they no longer found in Christianity. All the shocking anti-Communist propaganda and shopworn tributes to democracy that America could muster would fail to arrest the Marxian surge. But if Americans filled the spiritual vacuum, if they made religious faith commensurate with military and economic power, then Communism would dissipate."

The novelist, Wilfrid Sheed, became a close friend of the Luce family in the 1950s. He later wrote: "Harry was not as starchy as he looked (it would have been difficult), nor as puritanical... Over dinner, Harry would bark out his latest excitements like a kid in a show-and-tell class. He had always just discovered some red-hot theologian or a new theory about the American Proposition... He could not for the life of him see what people found wrong with him."

Henry Luce and Clare Booth Luce were strong opponents of Fidel Castro and his revolutionary government in Cuba. They joined forces with Hal Hendrix, Paul Bethel, William Pawley, Virginia Prewett, Dickey Chapelle, Edward Teller, Arleigh Burke, Leo Cherne, Ernest Cuneo, Sidney Hook, Hans Morgenthau and Frank Tannenbaum to form the Citizens Committee to Free Cuba (CCFC). On 25th March, 1963, the CCFC issued a statement: "The Committee is nonpartisan. It believes that Cuba is an issue that transcends party differences, and that its solution requires the kind of national unity we have always manifested at moments of great crisis. This belief is reflected in the broad and representative membership of the Committee."

The Luce family also funded Alpha 66. In 1962 Alpha 66 launched several raids on Cuba. This included attacks on port installations and foreign shipping. The authors of Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1981) argues that Clare Boothe Luce paid for one of the boats used in these raids: "The anti-communist blonde took a maternal interest in the three-man crew she adopted... She brought them to New York three times to mother them."

The Luce media empire led a campaign against the presidency of John F. Kennedy. As Richard D. Mahoney has pointed out: "The cause of liberating Cuba from Castro had become the grail of the Republican right. Life Magazine editorially adopted the cause of the exiles as its own, with photo essays on the raids.... Life's full-throttle opposition to Kennedy... was a problem for the administration. Along with Time, also published by Luce, it was one of the two or three most influential magazines in the country. In April, the president had invited the publisher and his very political wife to lunch at the White House. The Kennedy charm did nothing to deter or otherwise disarm them. The Luces walked out of the lunch to protest the president's warning to cool it on Cuba."

When Kennedy was assassinated, Charles Douglas Jackson purchased the Zapruder Film on behalf of Luce. David Lifton points out in The Great Zapruder Film Hoax (2004) that: "Abraham Zapruder in fact sold the film to Time-Life for the sum of $150,000 - about $900,000 dollars in today's money... Moreover, although Life had a copy of the film, it did little to maximize the return on its extraordinary investment. Specifically, it did not sell this unique property - as a film - to any broadcast media or permit it to be seen in motion, the logical way to maximize the financial return on its investment... A closer look revealed something else. The film wasn't just sold to Life - the person whose name was on the agreement was C. D. Jackson." Luce published individual frames of Zapruder's film but did not allow the film to be screened in its entirety.

Soon after the assassination Charles Douglas Jackson also successfully negotiated with Marina Oswald the exclusive rights to her story. Peter Dale Scott argues in his book Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (1996) that Jackson, on the urging of Allen Dulles, employed Isaac Don Levine, a veteran CIA publicist, to ghost-write Marina's story. This story never appeared in print.

Henry Luce remained active in right-wing politics and in 1964, campaigned for Barry Goldwater of Arizona, the Republican candidate for president. Later that year Henry and Clare Booth Luce retired to their home in Phoenix. He died there on on 28th February, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Wilfrid Sheed, Clare Boothe Luce (1982)

The possibility that there was a powerful mutual attraction hedged with normal lunges and hesitations seemed ruled out by their importance and ambition. Yet Harry was in fact precisely her type: physically, he was close enough to other men whom I know she finds interesting (although Harry photographed grimly) to suggest that their romance wasn't just power calling to power. Mentally, he was an extension of Baruch by other means: more global, but just as American, another confirmation of Mother's home truths. And morally, he was a decent man who knew his way in the jungle, like the heroine of The Women, like America in the world, as they both saw it.

Nevertheless, it was important for her to make clear for the record that he pursued her, because the non-record, or myth, ran all the other way. To begin with, Harry was already married and had two sons, not to mention two edifying magazines. The Other Woman was always public enemy number one in those days, whatever the circumstances; but in this case, the circumstances were bad too. Harry looked like a pillar of rectitude (an old Presbyterian trick-his sexual rectitude was to prove just about the national average) and he also looked absentminded, as if a smart woman could steal him while he wasn't looking.

Clare for her part lived in the scandal regions: a divorcee on the way up could hardly avoid one, even if she slept under armed guard. Wallis Simpson was the prototype of the day and Wallie's desperate maneuvering showed a thin-lipped world how villainous the type really was. So the record could say what it liked; the gossip had Clare reclining on a tiger skin all the way.

(2) David Halberstam, The Powers That Be (1979)

Luce's politics hardened in the postwar years and Time had become increasingly Republican in its tone. He had been stunned by Truman's defeat of Dewey in 1948. Then in the fall of 1949 China had fallen, the Democratic administration had failed to save Chiang, and that was too much; Truman, and even more Acheson, would have to pay the price. Time was now committed and politicized, an almost totally partisan instrument. The smell of blood was in the air. There was a hunger now in Luce to put a Republican back in power. It was as if Luce, between elections, stood as the leader of the opposition, a kingmaker who had failed to produce a king. The fall of China and the rise of a post-war anti-Communist mood had produced the essential issue to use against the Democrats: softness on Communism. If the Democrats for almost two decades had exploited the Great Depression as their essential issue-all Republicans wore top hats and forced all laboring men into breadlinesnow Republicans, with Luce at their forefront, were fixing on foreign affairs as the Democrats' Achilles' heel. It was a brutal time; serious foreign policy issues with emotional overtones were made more emotional by Luce; his magazine encouraged a kind of political primitivism. Time tried to convince its readers that the disaster in Asia had been caused by bad and unworthy Democrats at the State Department. It also encouraged them to think that a Republican administration would deal more forthrightly and more morally with the Communists, roll them back a little. Ttime's heroes during the late forties and early fifties were men like Foster Dulles and Douglas MacArthur, who talked of bringing moral standards to foreign affairs. Of MacArthur, Time was particularly worshipful, writing in that period when he was the Consul General of Japan: "Inside the Dai Ichi building, once the heart of a Japanese insurance empire, bleary-eyed staff officers looked up from stacks of papers, whispered proudly, 'God, the man is great.' General Almond, his chief of staff, said straight out, 'he's the greatest man alive.' And reverent Air Force General George E. Stratemeyer put it as strongly as it could be put. ..'he's the greatest man in history."' Acheson was the villain, savaged by Luce in those years. Clearly Acheson was not a patch on MacArthur: "What people thought of Dean Gooderham Acheson ranged from the proposition that he was a fellow traveller, or a wool-brained sower of `seeds of jackassery,' or an abysmally uncomprehending man, or a warmonger who was taking the U.S. into a world war, to the warm if not so audible defense that he was a great Secretary of State." Clearly the lines were being drawn. Luce had once told Felix Belair that Belair did not understand what being a Republican really meant, that it was like being part of a family.

(3) Jonathan P. Herzog, The Spiritual-Industrial Complex: America's Religious Battle Against Communism in the Early Cold War (2011)

Two advisers significantly shaped Luce's understanding of Communism's designs and weaknesses. The first was his wife, Clare Boothe Luce, for whom Communism was an evil religion that could only be met with the fiery zeal of a Christian nation. The second was Whittaker Chambers, the Communist turned Christian warrior. Chambers slowly climbed through the ranks of Time, Inc. and had entered the inner circle of advisers that Luce depended on for business and editorial decisions. In 1944 Luce made Chambers the head of Time's Foreign News. Predictably, Chambers molded Time into an anti-Communist mouthpiece....

While he counted anti-Communists like Mundt, Cardinal Spellman, and Chambers as allies, he viewed the Communist threat differently. In his view, it was a symptom and not a disease. Like his wife, Clare, he understood faith as a psychological imperative sought by all people. If religious faith waned, other dogmas would take its place. The success of Communism, then, was not attributable to its message but rather to the fact that it offered people the spiritual certainty they no longer found in Christianity. All the shocking anti-Communist propaganda and shopworn tributes to democracy that America could muster would fail to arrest the Marxian surge. But if Americans filled the spiritual vacuum, if they made religious faith commensurate with military and economic power, then Communism would dissipate.

Though his knowledge of Communism may have been underdeveloped, Luce spoke on religious matters with justified authority. Employees considered Luce's insistence upon riding alone in the elevator the thirty-six floors to his penthouse each morning a sign of elitism, but he actually took that time to pray. Luce was the son of Christian missionaries to China, and his father, a professor of theology, endowed him with a level of religious knowledge uncommon in businessmen of the age. Luce delighted in speaking before religious groups and fancied himself an amateur theologian. He was active in the Federal Council of Churches and the National Conference of Christians and Jews, and he sat on the board of directors of Union Theological Seminary.

(4) Drew Pearson, Diaries 1949-1959 (1974)

Life magazine is always pulling chestnuts out of the fire for the CIA; and I recall that C. D. Jackson of the Life-Time empire was the man who arranged for the CIA to finance the Freedom Balloons. C. D. Jackson, Harold Stassen and the other boys who went with me to Germany spent money like money while I paid my own way. I always was suspicious that a lot of dough was coming from unexplained quarters and didn't learn until sometime later that the CIA was footing the bill.

(5) Warren Hinckle & William Turner, Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1981)

Henry Robinson Luce, Lord High Admiral of the free world's greatest fleet of publications, believed fervently in God, flag, and Time, Inc., although not necessarily in that order. His blonde wife, Clare Boothe Luce, the former ambassador to Italy, was the princess regent of the respectable right wing. As a pair, Mr. and Mrs. Luce were face cards at any party. As one, they put down their silver forks on the dessert china imprinted with the blue of the presidential seal, and walked out of the White House lunch. Their host, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, had reason to be distressed at this unceremonious departure. He had arranged this special lunch in the spring of 1963 to convince the bellicose Lucepress to tone down its coverage of the exile raids and leave Cuba to the devices of the President. The luncheon instead turned out to be the Bay of Pigs of Kennedy's press relations.

(6) Gaeton Fonzi, The Last Investigation (1993)

One of the first leads Schweiker asked me to check came from a source he considered impeccable: Clare Boothe Luce. One of the wealthiest women in the world, widow of the founder of the Time, Inc. publishing empire, former member of the U.S. House of Representatives, former Ambassador to Italy, successful Broadway playwright, international socialite and longtime civic activist, Clare Boothe Luce was the last person in the world Schweiker would have suspected of leading him on a wild goose chase.

Yet the chase began almost immediately. Right after Schweiker announced the formation of his Kennedy assassination Subcommittee, he was visited by Vera Glaser, a syndicated Washington columnist. Glaser told him she had just interviewed Clare Boothe Luce and that Luce had given her some information relating to the assassination. Schweiker immediately called Luce and she, quite cooperatively and in detail, confirmed the story she had told Glaser.

Luce said that some time after the Bay of Pigs she received a call from her "great friend" William Pawley, who lived in Miami. A man of immense wealth-he had made his millions in oil-during World War II Pawley had gained fame setting up the Flying Tigers with General Claire Chennault. Pawley had also owned major sugar interests in Cuba, as well as Havana's bus, trolley and gas systems and he was close to both pre-Castro Cuban rulers, President Carlos Prio and General Fulgencio Batista. (Pawley was one of the dispossessed American investors in Cuba who early tried to convince Eisenhower that Castro was a Communist and urged him to arm the exiles in Miami.)

Luce said that Pawley had gotten the idea of putting together a fleet of speedboats-sea-going "Flying Tigers" as it were-which would be used by the exiles to dart in and out of Cuba on "intelligence gathering" missions. He asked her to sponsor one of these boats and she agreed. As a result of her sponsorship, Luce got to know the three-man crew of the boat "fairly well," as she said. She called them "my boys" and said they visited her a few times in her New York townhouse. It was one of these boat crews, Luce said, that originally brought back the news of Russian missiles in Cuba. Because Kennedy didn't react to it, she said she helped feed it to Senator Kenneth Keating, who made it public. She then wrote an article for Life magazine predicting the missile crisis. "Well, then came the nuclear showdown and the President made his deal with Khrushchev and I never saw my young Cubans again," she said. The boat operations were stopped, she said, shortly afterwards when Pawley was notified that the U.S. was invoking the Neutrality Act and would prevent any further exile missions into Cuba.

Luce said she hadn't thought about her boat crew until the day that President Kennedy was killed. That evening she received a telephone call from one of the crew members. She told Schweiker his name was "something like" Julio Fernandez, and he said he was calling her from New Orleans. Julio Fernandez told her that he and the other crew members had been forced out of Miami after the Cuban missile crisis and that they had started a "Free Cuba" cell in New Orleans. Luce said that Fernandez told her that Oswald had approached his group and offered his services as a potential Castro assassin. He said his group didn't believe Oswald, suspected he was really a Communist and decided to keep tabs on him. Fernandez said they found that Oswald was, indeed, a Communist, and they eventually penetrated his "cell" and tape-recorded his talks, including his bragging that he could shoot anyone because he was "the greatest shot in the world with a telescopic lens." Fernandez said that Oswald then suddenly came into money and went to Mexico City and then Dallas. According to Luce, Fernandez also told her that his group had photographs of Oswald and copies of handbills Oswald had been distributing on the streets of New Orleans. Fernandez asked Luce what he should do with this information and material.

(7) Richard D. Mahoney, Sons and Brothers: The Days of Jack and Bobby Kennedy (1999)

The situation meanwhile among the anti-Castro exiles in south Florida was taking on the character of an undeclared rebellion against the official cease-and-desist policy of the Kennedy administration. On March 18, Alpha 66, with the guidance of the CIA's David Phillips, launched an attack on the island of Isabela de Sagua, wounding twelve Soviet soldiers and damaging the Russian freighter Lvov. Later that month, exiled Cuban fighters in Commandos L group blew up and sank the Russian merchantman Baku off the coast of Cuba. The Soviet Union delivered an angry protest to the United States. Washington assured Moscow it would control the raids. In a press conference, the president noted that such sorties could renew hostilities between the superpowers if they were not stopped.

His exasperation was not shared by others in Washington. By this time the cause of liberating Cuba from Castro had become the grail of the Republican right. Life magazine editorially adopted the cause of the exiles as its own, with photo essays on the raids. Clare Booth Luce, the powerful wife of Life publisher Henry R Luce and, herself a former congresswoman and United States ambassador, helped finance an anti-Castro platoon - an action that years later pulled her into the investigation of the conspiracy to kill President Kennedy.

Life's full-throttle opposition to Kennedy "appeasement" was a problem for the administration. Along with Time, also published by Luce, it was one of the two or three most influential magazines in the country. In April, the president had invited the publisher and his very political wife to lunch at the White House. The Kennedy charm did nothing to deter or otherwise disarm them. The Luces walked out of the lunch to protest the president's warning to cool it on Cuba.

(8) Larry Hancock, Someone Would Have Talked (2006)

In the spring of 1960, Phillips began work on propaganda for the new Cuban Project. His activities from 1960 through 1961 frequently took him to the Miami JM/WAVE station and he also engaged in counter intelligence work against the FPCC. He met routinely with exile groups including the CRC (The Night Watch makes no mention of Alpha 66). JM/WAVE personnel have said that Phillips continued to maintain contact with and use Cubans that he had originally met in Havana, and continued this into his next assignment after the Bay of Pigs in Mexico City.

Virginia Prewett appears to have been one of Phillips' significant media contacts and certainly one of the most consistent sources of media coverage for Alpha 66 activities.

The other major source was Life magazine, part of the Luce Media family managed by Claire Booth Luce's husband Henry Robinson "Harry" Luce (a member of the Citizens Committee to Free Cuba, along with Phillips' friends Hal Hendrix and Paul Bethel). Articles by Prewitt and editorials by Time-Life provided the strongest challenge to the Kennedy position on Cuba and were quite consistent with the type of embarrass and back-to-the wall agendas Veciana attributed to Maurice Bishop...

David Phillips also became good friends with Paul Bethel. During his time in Cuba, Bethel was a US AID employee handling public relations. He and Phillips both participated in amateur theatricals in Cuba. Later, Bethel apparently became a key part of the media and political network that would represent one of David Phillips' major achievements in anti-Castro propaganda. Bethel's own politics were right-wing and "Red Menace" oriented. Paul Bethel had worked on a trial basis for JMWAVE from October - December, 1961 as a writer and analyst on Cuban press and press plans. He was released when JMWAVE determined that his contributions did not justify his $1,000 per month salary (after leaving USAID upon his return to Miami, Bethel was employed on a trial basis by JMWAVE from Oct-Dec of 1961).

Bethel was only one of Phillips associates who seem to have held aggressively conservative political agendas-friends with whom the supposedly apolitical Phillips established strong bonds. Phillips' friends included Claire Booth Luce of the Luce magazine empire and Gordon McLendon, founder of national radio and movie chains. Claire Booth Luce, once ambassador to Italy, was not known for her restrained remarks, once remarking that Vietnamese Buddhist monks who died in flames had "made a good deal for themselves" by assuring their own sainthood.

(9) Carl Bernstein, CIA and the Media, Rolling Stone Magazine (20th October, 1977)

In 1953, Joseph Alsop, then one of America’s leading syndicated columnists, went to the Philippines to cover an election. He did not go because he was asked to do so by his syndicate. He did not go because he was asked to do so by the newspapers that printed his column. He went at the request of the CIA.

Alsop is one of more than 400 American journalists who in the past twenty-five years have secretly carried out assignments for the Central Intelligence Agency, according to documents on file at CIA headquarters.

Some of these journalists’ relationships with the Agency were tacit; some were explicit. There was cooperation, accommodation and overlap. Journalists provided a full range of clandestine services - from simple intelligence gathering to serving as go-betweens with spies in Communist countries. Reporters shared their notebooks with the CIA. Editors shared their staffs. Some of the journalists were Pulitzer Prize winners, distinguished reporters who considered themselves ambassadors-without-portfolio for their country. Most were less exalted: foreign correspondents who found that their association with the Agency helped their work; stringers and freelancers who were as interested it the derring-do of the spy business as in filing articles, and, the smallest category, full-time CIA employees masquerading as journalists abroad. In many instances, CIA documents show, journalists were engaged to perform tasks for the CIA with the consent of the managements America’s leading news organizations.

The history of the CIA’s involvement with the American press continues to be shrouded by an official policy of obfuscation and deception...

Among the executives who lent their cooperation to the Agency were William Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System, Henry Luce of Time Inc., Arthur Hays Sulzberger of the New York Times, Barry Bingham Sr. of the Louisville Courier-Journal and James Copley of the Copley News Service. Other organizations which cooperated with the CIA include the American Broadcasting Company, the National Broadcasting Company, the Associated Press, United Press International, Reuters, Hearst Newspapers, Scripps-Howard, Newsweek magazine, the Mutual Broadcasting System, The Miami Herald, and the old Saturday Evening Post and New York Herald-Tribune. By far the most valuable of these associations, according to CIA officials, have been with The New York Times, CBS, and Time Inc.

From the Agency’s perspective, there is nothing untoward in such relationships, and any ethical questions are a matter for the journalistic profession to resolve, not the intelligence community...

Many journalists were used by the CIA to assist in this process and they had the reputation of being among the best in the business. The peculiar nature of the job of the foreign correspondent is ideal for such work; he is accorded unusual access, by his host country, permitted to travel in areas often off-limits to other Americans, spends much of his time cultivating sources in governments, academic institutions, the military establishment and the scientific communities. He has the opportunity to form long-term personal relationships with sources and -- perhaps more than any other category of American operative - is in a position to make correct judgments about the susceptibility and availability of foreign nationals for recruitment as spies.

The Agency’s dealings with the press began during the earliest stages of the Cold War. Allen Dulles, who became director of the CIA in 1953, sought to establish a recruiting-and-cover capability within America’s most prestigious journalistic institutions. By operating under the guise of accredited news correspondents, Dulles believed, CIA operatives abroad would be accorded a degree of access and freedom of movement unobtainable under almost any other type of cover.

American publishers, like so many other corporate and institutional leaders at the time, were willing us commit the resources of their companies to the struggle against “global Communism.” Accordingly, the traditional line separating the American press corps and government was often indistinguishable: rarely was a news agency used to provide cover for CIA operatives abroad without the knowledge and consent of either its principal owner; publisher or senior editor. Thus, contrary to the notion that the CIA era and news executives allowed themselves and their organizations to become handmaidens to the intelligence services. “Let’s not pick on some poor reporters, for God’s sake,” William Colby exclaimed at one point to the Church committee’s investigators. “Let’s go to the managements. They were witting” In all, about twenty-five news organizations (including those listed at the beginning of this article) provided cover for the Agency...

Many journalists who covered World War II were close to people in the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime predecessor of the CIA; more important, they were all on the same side. When the war ended and many OSS officials went into the CIA, it was only natural that these relationships would continue.

Meanwhile, the first postwar generation of journalists entered the profession; they shared the same political and professional values as their mentors. “You had a gang of people who worked together during World War II and never got over it,” said one Agency official. “They were genuinely motivated and highly susceptible to intrigue and being on the inside. Then in the Fifties and Sixties there was a national consensus about a national threat. The Vietnam War tore everything to pieces - shredded the consensus and threw it in the air.” Another Agency official observed: “Many journalists didn’t give a second thought to associating with the Agency. But there was a point when the ethical issues which most people had submerged finally surfaced. Today, a lot of these guys vehemently deny that they had any relationship with the Agency.”

The CIA even ran a formal training program in the 1950s to teach its agents to be journalists. Intelligence officers were “taught to make noises like reporters,” explained a high CIA official, and were then placed in major news organizations with help from management. “These were the guys who went through the ranks and were told, “You’re going to be a journalist,” the CIA official said. Relatively few of the 400-some relationships described in Agency files followed that pattern, however; most involved persons who were already bona fide journalists when they began undertaking tasks for the Agency. The Agency’s relationships with journalists, as described in CIA files, include the following general categories:

* Legitimate, accredited staff members of news organizations - usually reporters. Some were paid; some worked for the Agency on a purely voluntary basis.

* Stringers and freelancers. Most were payrolled by the Agency under standard contractual terms.

* Employees of so-called CIA “proprietaries.” During the past twenty-five years, the Agency has secretly bankrolled numerous foreign press services, periodicals and newspapers -- both English and foreign language -- which provided excellent cover for CIA operatives.

* Columnists and commentators. There are perhaps a dozen well-known columnists and broadcast commentators whose relationships with the CIA go far beyond those normally maintained between reporters and their sources. They are referred to at the Agency as “known assets” and can be counted on to perform a variety of undercover tasks; they are considered receptive to the Agency’s point of view on various subjects.

Murky details of CIA relationships with individuals and news organizations began trickling out in 1973 when it was first disclosed that the CIA had, on occasion, employed journalists. Those reports, combined with new information, serve as casebook studies of the Agency’s use of journalists for intelligence purposes.

The New York Times - The Agency’s relationship with the Times was by far its most valuable among newspapers, according to CIA officials. [It was] general Times policy to provide assistance to the CIA whenever possible...