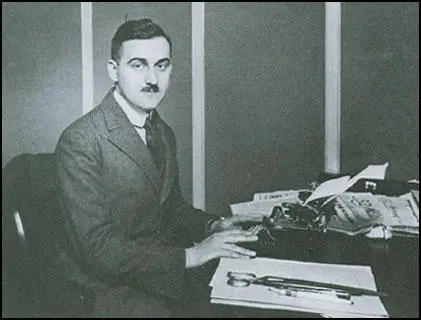

George Seldes

George Seldes was born in Alliance, New Jersey, on 16th November, 1890. When he was nineteen he was employed as a cub reporter by the Pittsburgh Leader. In his autobiography, Witness to a Century (1987) he admitted that as a young man he was influenced by investigative journalists such as Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair and Ray Stannard Baker.

Seldes interviewed William Haywood and Joe Hill in 1912: "When Bill Hayward came to the coal and iron capital of America, Ray Springle and I went to his headquarters, not for news stories, which we knew would never be published, but out of interest in the new labor movement, the Industrial Workers of the World. And so, by chance along with its new leaders we met the ballad-maker of the IWW, Joe Hill." Seldes later recalled: "Joe Hill was a man of great enthusiasm and such easy friendship that in the week or ten days in which we knew him the three of us and another of his friends pledged a lifetime of loyalty to one another. But it was only a few months later that the last member of our foursome... sent me a photograph of Joe Hill sitting upright in his coffin with five bullet holes in his left chest."

In 1914 Seldes was appointed night editor of the Pittsburgh Post. As a young man he was influenced by the investigative journalism of Lincoln Steffens. He later wrote: "Lincoln Steffens was the godfather of us all. He was an older man when I first met him. He was the first of the muckrakers.... He often warned me that I was starting to get a bad reputation for myself. I guess I never worried about that."

In 1916 Seldes moved to London where he worked for the United Press. When the United States joined the First World War in 1917, Seldes was sent to France where he worked as the war correspondent for the Marshall Syndicate. At end of the war he managed to obtain an exclusive interview with Paul von Hindenburg. Unfortunately for Seldes, the article was suppressed and never appeared in the American press.

Seldes spent the next ten years as an international reporter for the Chicago Tribune. In the summer of 1921, Seldes was sent to Russia to report on the new policy of war communism in Russia. Maxim Litvinov was placed in charge of giving permission to the journalists to go into the famine areas. Those who arrived from the United States included Floyd Gibbons and Walter Duranty. Seldes later commented in his autobiography, Witness to a Century (1987): "We had been instructed to proceed to the Hotel Savoy, a small hostelry near the Kremlin, and we were assigned rooms on the second or third floor. But Floyd Gibbons had beaten all of us to Moscow. We heard that he was now in Sumara, the worst-hit city in the famine zone."

According to Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990): "Floyd Gibbons arrived in Russia in order to report, now a dashing figure with his black eye patch, had chartered a plane and told Litvinov he planned to fly into Red Square in it, giving his paper a big scoop. Appalled at the prospect, Litvinov instead offered Gibbons the chance to go early into the area stricken by famine, exactly what Gibbons had been after all along. Once into the Ukraine, Gibbons sent his dispatches back by messenger and by train to Moscow, where they were cabled directly to the United States." Duranty of the New York Times said that Gibbons "fully deserved his success because he had accomplished the feat of bluffing the redoubtable Litvinov stone-cold... a noble piece of work." Over the next few days Gibbons was the only reporter to document the horrifying prospect of the deaths of as many as fifteen million people from starvation.

After Floyd Gibbons returned to Moscow he issued instructions to Seldes: "Floyd now returned to Moscow, made me officially his Russian correspondent, and sent me off to Samara, instructing me to evade the censorship by every trick known to the profession. By the time I was able to go to Samara - about a month later - there were no longer people lying dead on the streets... and every American was treated as a benefactor. (In Moscow officialdom tried its best to make believe there was no famine, no American aid saving millions of lives.)"

Seldes was a regular visitor to the home of Walter Duranty, the New York Times correspondent in Moscow. Seldes later recalled that Duranty was the "kind of man who wouldn't hesitate to attempt sexual conquests with his wife present." They employed a young cook, who Seldes described as "a very pretty peasant girl... pretty and young and vivacious and all of that; and tall, for a Russian." According to Seldes the young woman quickly became Duranty's mistress and Jane did not appear to be terribly upset by the arrangement.

In 1922 Seldes managed to get an interview with the Bolshevik leader, Lenin. "He spoke with a thick, throaty, wet voice. He was in very good humour, always smiling, his face never was hard. All his pictures are hard but he was always twinkling with laughter. Eyes bright, crowsfeet, a real, unserious face... Lenin had the greatness and the human, all-too-human sympathy to be a comrade to all, the group of fellow dictators and the peasants who loved him. In battle with his enemies he was uncompromising and without pity. He hated power, knowing its corruption. His political wisdom was great; he understood mob psychology thoroughly but was a little weak in his grasp of individual psychology; he never made a mistake in dealing with the masses but he frequently did in choosing men to share power."

However, the Soviet government did not like Seldes's reports and in 1923 he was expelled from the country. Seldes later reported that the main problem was the role played by Cheka in the Soviet Union: "Freedom, liberty, justice as we know it, democracy, all the fundamental human rights for which the world has been fighting for civilized centuries, have been abolished in Russia in order that the communist experiment might be made. They have been kept suppressed by the Cheka."

In a series of articles in the Chicago Tribune Seldes described the Soviet Union as a police state of unparalled ruthlessness. In one article Seldes commented "believe me, if Bolshevism ever comes to America nothing would please me more than a nice corner position on a roof overlooking two main streets and a nice large machine gun and unlimited belts of ammunition." Duranty responded by defending the country. He argued that: "freedom of speech and the press in America and England are the slow outcome of a centuries long fight for personal freedom. How can you expect Russia, just emerged from blackest tyranny, to share the attitude of Anglo-Saxons who struck the blow against royal tyrants a thousand years ago at Runnymede?"

The editor of the Chicago Tribune sent him to Italy where he wrote about Benito Mussolini and the rise of fascism. Seldes investigated the murder of Giacomo Matteotti, the head of the Italian Socialist Party. "Everyone had copies of the confessions of the men who killed Giacomo Matteotti (the head of the Italian Socialist Party and Mussolini's chief political rival). The documents clearly implicated Mussolini in the killing, but not one person wanted to write about it. They thought Rome was too nice a posting to give up to risk publishing them. They didn't want to, but I did. The major American newspapers at the time supported fascism as a legitimate political movement. They loved Mussolini because they thought he restored order to Italy and businesses there were doing well. It got more and more difficult to report on what was really happening there." His article implicating Mussolini in the killing, resulted in Seldes being expelled from Italy.

The Chicago Tribune sent Seldes to Mexico in 1927 but his articles criticizing American corporations concerning their use of the country's mineral rights, were not always published by the newspaper. Seldes returned to Europe but found that increasingly his work was being censored to fit the political views of the newspaper's owner, Robert McCormack.

Disillusioned, Seldes left the Chicago Tribune and worked as a freelance writer. In his first two books, You Can't Print That! (1929) and Can These Things Be! (1931), Seldes included material that he had not been allowed to publish in the newspaper. His next book, World Panorama (1933), was a narrative history of the period that followed the First World War.

In 1934 Seldes published a history of the Catholic Church, The Vatican. This was followed by an expose of the world armaments industry, Iron, Blood and Profits (1934), an account of Benito Mussolini, appeared in Sawdust Caesar (1935), and two books on the newspaper industry, Freedom of the Press (1935) and Lords of the Press (1938). During this period he also reported on the Spanish Civil War for the New York Post.

On his return to the United States in 1940 Seldes published Witch Hunt: The Techniques and Profits of Redbaiting, an account of the persecution of people with left-wing political views in America, and The Catholic Crisis, where he attempted to show the close relationship between the Catholic Church and fascist organizations in Europe.

In 1940 Seldes began his own political newsletter called In Fact. A journal that eventually reached a circulation of 176,000. One of the first articles published in the newsletter concerned the link between cigarette smoking and cancer. Seldes later explained that at the time, "The tobacco stories were suppressed by every major newspaper. For ten years we pounded on tobacco as being one of the only legal poisons you could buy in America."

As well as writing his newsletter Seldes continued to publish books. This included Facts and Fascism (1943), 1000 Americans (1947), an account of the people who controlled America and The People Don't Know (1949) on the origins of the Cold War.

Herbert Block, Washington Post (7th May, 1954)

In the early 1950s Seldes work came under attack from Joseph McCarthy. Despite his long history of being hostile to all forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism, he was accused of being a communist. He later recalled how: "Newspaper columnists would write that a Russian agent stopped by my office each week to pay my salary. I didn't have the money to sue them for libel. My lawyer told me it would take years to reach a settlement and even if I won I would never see a dime."

Seles was blacklisted and now found it difficult to get his journalism published. He continued to write books including Tell the Truth and Run (1953), Never Tire of Protesting (1968), Even the Gods Can't Change History (1976) and Witness to a Century (1987).

George Seldes died at Windsor, Vermont, on 2nd July, 1995, aged 104.

Primary Sources

(1) George Seldes, interviewed Paul von Hindenburg at the end of the First World War. It was censored at the time but appeared in his book You Can't Print That! (1929)

We were doing almost all the fighting while the Allies were marching unhindered into famous cities and famous battle fields of 1914, and capturing the headlines of the world. We were losing men and taking prisoners and trenches - fighting most of the war then and getting no credit from the press because our work was not spectacular. Hindenburg and Pershing knew what we were doing. What would Hindenburg say?

"I will reply with the same frankness," said Hindenburg, faintly amused at our diplomacy. " The American infantry in the Argonne won the war."

He paused and we sat thrilled.

" I say this," continued Hindenburg, " as a soldier, and soldiers will understand me best.

"To begin with I must confess that Germany could not have won the war - that is, after 1917. We might have won on land. We might have taken Paris. But after the failure of the world food crops of 1916 the British food blockade reached its greatest effectiveness in 1917. So I must really say that the British food blockade of 1917 and the American blow in the Argonne of 1918 decided the war for the Allies.

"But without American troops against us and despite a food blockade which was undermining the civilian population of Germany and curtailing the rations in the field, we could still have had a peace without victory. The war could have ended in a sort of stalemate.

"In the summer of 1918 the German army was able to launch offensive after offensive - almost one a month. We had the men, the munitions and the morale, and we were not overbalanced. But the balance was broken by the American troops.

"The Argonne battle was slow and difficult. But it was strategic. It was bitter and it used up division after division. We had to hold the Metz-Longuyon roads and railroad and we had hoped to stop all American attacks until the entire army was out of northern France. We were passing through the neck of a vast bottle. But the neck was narrow. German and American divisions fought each other to a standstill in the Argonne. They met and shattered each other's strength. The Americans are splendid soldiers. But when I replaced a division it was weak in numbers and unrested, while each American division came in fresh and fit and on the offensive.

"The day came when the American command sent new divisions into the battle and when I had not even a broken division to plug up the gaps. There was nothing left to do but ask terms.

(2) George Seldes, Witness to a Century (1987)

If the Hindenburg interview had been passed by Pershing's (stupid) censors at the time, it would have been headlined in every country civilized enough to have newspapers and undoubtedly would have made an impression on millions of people and became an important page in history. I believe it would have destroyed the main planks on which Hitler rose to power, it would have prevented World War II, the greatest and worst war in all history, and it would have changed the future of all mankind.

(3) George Seldes wrote about Benito Mussolini in his book You Can't Print That! (1929)

He began coldly, in a voice northern and unimpassioned. I had never heard an Italian orator so restrained. Then he changed, became soft and warm, added gestures, and flames in his eyes. The audience moved with him. He held them. Suddenly he lowered his voice to a heavy whisper and the silence among the listeners became more intense. The whisper sank lower and the listeners strained breathlessly to hear. Then Mussolini exploded with thunder and fire, and the mob - for it was no more than a mob now - rose to its feet and shouted. Immediately Mussolini became cold and nordic and restrained again and swept his mob into its seats exhausted. An actor. Actor extraordinary, with a country for a stage, a great powerful histrionic ego, swaying an audience of millions, confounding the world by his theatrical cleverness.

(4) George Seldes, interviewed by Randolph T. Holhut (1992)

Everyone had copies of the confessions of the men who killed Giacomo Matteotti (the head of the Italian Socialist Party and Mussolini's chief political rival). The documents clearly implicated Mussolini in the killing, but not one person wanted to write about it. They thought Rome was too nice a posting to give up to risk publishing them. They didn't want to, but I did. The major American newspapers at the time supported fascism as a legitimate political movement. They loved Mussolini because they thought he restored order to Italy and businesses there were doing well. It got more and more difficult to report on what was really happening there.

(5) George Seldes wrote about Cheka in his book You Can't Print That! (1929)

The Cheka (Chesvychaika), or GPU, is the instrument of the red terror, organized in 1918, through which the Soviet government, the Communist party and the Third International, Russia's indivisible trinity, maintains itself in dictatorial power to this very day. The years have brought a change in name, less activity, more secrecy.

The era of wanton murder has passed, it is true; public trials within fourteen days after arrest are now ordered by law and in most cases given. But the terror has entered into the souls of the Russian people.

Because of the Cheka, freedom has ceased to exist in Russia. There is no democracy. It is not wanted. Only American apologists for the Soviets have ever pretended there was democracy in Russia. " Democracy " says a communist axiom " is a delusion of the bourgeois mind." Justice in Russia is communist justice: the end justifies the means, and the end is Communism at all costs, including the lives of its opponents.

Freedom, liberty, justice as we know it, democracy, all the fundamental human rights for which the world has been fighting for civilized centuries, have been abolished in Russia in order that the communist experiment might be made. They have been kept suppressed by the Cheka.

The Cheka is the instrument of militant Communism. It is a great success. The terror is in the mind and marrow of the present generation and nothing but generations of freedom and liberty will ever root it out.

The victims of the Cheka are estimated anywhere from 50,000 to 500,000, with the truth probably mid-ways. But it is not a matter of numbers. The outstanding fact today is that by their tortures, wholesale arrests and wholesale murders of liberals suspected of not favouring the Bolshevik interpretation of Communism, the Cheka has terrorized a whole generation, the people of our time.

The victims are usually non-Bolshevik radicals, especially Socialists, social-revolutionaries and Mensheviks, who, incidentally, are more hated by the Bolsheviks than the capitalists, the nobility or the bourgeoisie.

(6) George Seldes, You Can't Print That! (1929)

Many people trembled when the name of the dictator was mentioned. But in dirty little offices sat little grey bureaucrats who changed Lenin's speeches when they feared he had spoken too dangerously, and in other dirty little offices sat military political police officials who bragged that they would arrest the man if he acted too dangerously.

When we said to the censors, Lenin himself said this, they laughed. When it served their purposes they added or deleted, and sometimes they suppressed Lenin entirely. When it pleased them they arranged interviews, but for years they did their best to keep the " capitalist" journalists out of Lenin's sight. We heard him, however, at all the big congresses.

He spoke with a thick, throaty, wet voice. He was in very good humour, always smiling, his face never was hard. All his pictures are hard but he was always twinkling with laughter. Eyes bright, crowsfeet, a real, unserious face. He had a clever motion of the hand by which he could emphasize a point and yet steal a look at the time on his wrist watch. Frequently he pointed with both index fingers, upwards, shoulder high, like the conventional picture of a Chinese dancer.

He was dressed in a cheap grey semi-military uniform, a civilian transplanted into ill-fitting army-issue clothes. They were grey-black but the crease in the trousers was already giving because there is too much shoddy in the wool. The tunic, which is high like the American doughboy's, was open at the neck revealing a flannel shirt and a bright blue necktie, loosely tied. His eyes were not half as oriental as the photographs have made him, because he has full eyebrows, not merely stubs at the nose, which the pictures emphasize.

He reported on foreign and domestic affairs. He never hesitated to acknowledge defeats and failures. But he was always optimistic. My disillusion was profound. I wondered how this man, who has so little magnetism, had come to the fore in a radical environment where spell-binding oratory, silver-tongued climaxes, soap-box repartee, have been the road to success. Only once did he aim to produce a laugh, and even that had his touch of irony. "We have pruned and pruned our bureaucracy," he said, "and after four years we have taken a census of our government staff and we have an increase of 12,000."

Lenin had the greatness and the human, all-too-human sympathy to be a comrade to all, the group of fellow dictators and the peasants who loved him. In battle with his enemies he was uncompromising and without pity. He hated power, knowing its corruption. His political wisdom was great; he understood mob psychology thoroughly but was a little weak in his grasp of individual psychology; he never made a mistake in dealing with the masses but he frequently did in choosing men to share power.

(7) George Seldes, interviewed by Randolph T. Holhut (1992)

Lincoln Steffens was the godfather of us all. He was an older man when I first met him (in 1919). He was the first of the muckrakers. As he once said, "where there's muck, I'll rake it." He often warned me that I was starting to get a bad reputation for myself. I guess I never worried about that.

(8) George Seldes, Lords of the Press (1938)

The failure of a free press in most countries is usually blamed on the readers. Every nation gets the government--and the press - it deserves. This is too facile a remark. The people deserve better in most governments and press. Readers, in millions of cases, have no way of finding out whether their newspapers are fair or not, honest or distorted, truthful or colored.

There are less than a dozen independent newspapers in the whole country, and even that small number is dependent on advertisers and other things, and all these other things which revolve around money and profit make real independence impossible. No newspaper which is supporting one class of society is independent.

(9) George Seldes, Tell the Truth and Run (1953)

The middle of the road is a crowded place. During all these years of work and talk I had had a fine contempt for the frightened majority which traveled the middle road. I had thought of myself as one of the non-conformists along the less-traveled and rather lonely individual path of my choosing.

(10) George Seldes, In Fact (1942)

Question: Can you trust the press?

George Seldes: The baseball scores are always correct (except for a typographical error now and then). The stock market tables are correct (within the same limitation). But when it comes to news which will affect you, your daily life, your job, your relation to other peoples, your thinking on economic and social problems, and, more important today, your going to war and risking your life for a great ideal, then you cannot trust about 98 percent (or perhaps 99 1/2 percent) of the big newspaper and big magazine press of America.

Question: But why can't you trust the press?

George Seldes: Because it has become big business. The big city press and the big magazines have become commercialized, or big business organizations, run with no other motive than profit for owner or stockholder (although hypocritically still maintaining the old American tradition of guiding and enlightening the people). The big press cannot exist a day without advertising. Advertising means money from big business.

(11) A. J. Liebling, The Wayward Pressman (1947)

George Seldes about as subtle as a house falling in. He makes too much of the failure of newspapers to print exactly what George Seldes would have printed if he were the managing editor. But he is a useful citizen. In fact is a fine little gadfly, representing an enormous effort for one man and his wife.

(12) George Seldes, interviewed by Randolph T. Holhut (1992)

A lot of people call here and say "I didn't know you were still alive." For a long time, my name never appeared in the papers. People thought "this guy is a troublemaker, the hell with him." I never had it easy, but I never missed a meal and I've never been broke.

One of the greatest sources of comfort to me is knowing that I have lived long enough to be vindicated. I've outlived all of my enemies, but I've also outlived all of my friends.