Matthew Boulton

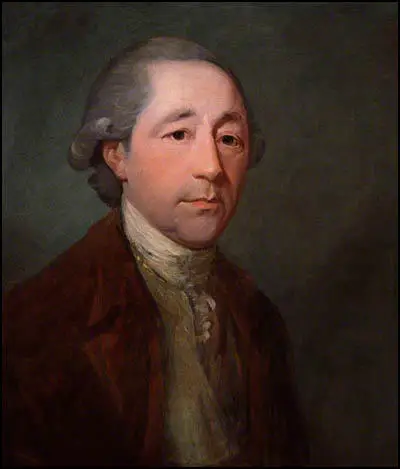

Matthew Boulton, the son of Matthew Boulton. a silver-stamper and toy maker, was born in Birmingham on 14th September 1728. His name had originally been given to the first-born son, who had died at the age of two in 1726. Although he had a brother, John, and two sisters, as he grew up it was he who carried his father's hopes." (1)

Matthew was educated at the Nonconformist academy run by John Hausted in Deritend and joined the family business on leaving school. The company was a maker of toys, this was the general name for small metal goods such as "gold and silver toys produced trinkets, snuff-boxes, inkstands... and steel toys, chiefly buckles for both shoes and knee-breeches". (2)

At the age of twenty-one he became a partner in his father's business. At that time the Birmingham toy trade employed 20,000 people. Distance from major rivers had pushed its tradesmen towards small-scale metal-working. Boulton told his father that he wanted to build the company into a dominant force in the city. (3) Jenny Uglow, the author of The Lunar Men (2002), has argued: "Boulton was neat and dark and dapper, with curly brown hair, keen eyes and a broad grin. Frank and humorous, always with an eye to the main chance, he was a man on the make." (4)

In 1756 Boulton married a distant cousin, Mary Robinson, the elder daughter of Luke Robinson, a merchant from Lichfield. On the death of her parents she inherited £14,000. Mary Boulton died in 1760 and there were no surviving children. His father also died around the same time, leaving the business to his son. Boulton later married Anne, Mary's younger sister. This was forbidden by ecclesiastical law but Boulton still went ahead with the wedding. According to his biographer, Jennifer Tann: "Boulton's marriage, and with it the addition to his fortune, was the cause of a number of letters of congratulations from his friends. Later in his life, alluding to his fortune, he remarked that he had had the option of living the life of a gentleman but chose, rather, to become an industrialist." (5)

Boulton decided to use his new wealth to expand his business to include other "mechanic inventions, toys and utensils of various kinds in gold, silver, steel, copper, tortoiseshell, enamels, and many vitreous and metallic compositions." (6)

Soho Manufactory

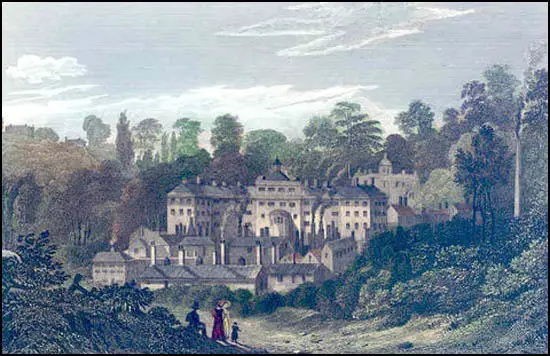

To achieve this he acquired the lease of a site on Handsworth Heath. In the summer 1761 he built dwellings for workmen, workshops, and a warehouse. The following year began to plan the construction of the Soho Manufactory. It was completed in 1766 and was considered to be Britain's very first factory.

Boulton also formed a partnership with John Fothergill, who could speak French and German and had good contacts in Europe. They also employed talented craftsmen from Europe an attempt to discover some of the secrets of manufacture. Soho was visited by foreign visitors. However, as Gavin Weightman has pointed out: "They could never be quite sure if their guest had an eye to steal their trade secrets, and a decision had to be taken about how much to show them, or whether to let them in at all." (7)

During this period he became friends with Erasmus Darwin, who had recently set up a medical practice in nearby Lichfield. "The chief bond between them was the love of invention and experiment. Very quickly they realized how they could complement each other. Darwin the university-educated theorist, Boulton the man with the technical know-how. equally outspoken, energetic and ebullient, they were two sides of a coin." (8)

Boulton also became friends Josiah Wedgwood, who ran his own business at Burslem. Wedgwood loved experimenting and invented what became known as green glaze. In 1763 he patented a beautiful cream-coloured pottery. Wedgwood visited his factory in May 1767. At the time Boulton was employing over 500 people and had a turnover of £30,000. Wedgewood was impressed as he only had a turnover of around £5,000. Wedgewood wrote to his friend, Thomas Bentley: "He is I believe the most complete manufacturer in England in England, in metal. He is very ingenious." (9)

The following year Boulton formed a partnership with Wedgwood. It was agreed that Wedgwood would supply plain ornamental vases which Boulton would finish by applying colourful gold and purple metal works (ormolu) to vases. Boulton told Wedgewood that he was convinced that they were going to "supplant the French in the gilt business" and would extend "the sale of it to every corner of Europe." (10) Unfortunately, Wedgwood was forced to have his leg amputated in April, 1767, and the arrangement was cancelled. (11)

In 1768 Boulton and Darwin formed what became known as the Lunar Society of Birmingham. The group took this name because they used to meet to dine and converse on the night of the full moon. Other members included Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley, James Brindley, Thomas Day, William Small, John Whitehurst, John Robison, Joseph Black, William Withering, John Wilkinson, Richard Lovell Edgeworth and Joseph Wright. This group of scientists, writers and industrialists discussed philosophy, engineering and chemistry. (12)

As Maureen McNeil has pointed out: "These innovating men of science and industry were drawn together by their interest in natural philosophy, technological and industrial development, and social change appropriate to these concerns. The society acquired its name because of the practice of meeting once a month on the afternoon of the Monday nearest the time of the full moon, but informal contacts among members were also important." (13)

Boulton acquired the technology for manufacturing Sheffield plate - a sheet of silver fused to one of copper and subsequently rolled. He used Sheffield plate to make a variety of articles, including candlesticks in different patterns, jugs, tureens, and cups. Boulton was the first to make plated telescope tubes for the London instrument maker Jesse Ramsden. (14)

Boulton was both an artisan innovator and a good salesman who obtained orders from around the world. Adolf Frederick, the King of Sweden, offered Boulton a business deal if he established a factory in his country. Boulton was to receive £500 for travelling expenses, an advance of £1,500 on equipment including waterwheels and a cut of 20 to 25 per cent on everything he exported. He was also promised exemption from import duty on English coal but he refused the offer. As he did when a similar deal from King Frederick II of Prussia. (15)

Matthew Boulton and James Watt

Boulton's factory used machines performing tasks such as turning lathes and stamping sheet metal. The engines of these machines were driven by a water mill, but the water source was always running dry, either from drought or diversion to the Birmingham Canal. Boulton and some of his friends at the Lunar Society had many discussions about the possibility of developing an engine powered by steam. (16) Darwin was especially involved in these experiments but he had to admit that he was unable to overcome the problems that Boulton faced. (17)

In March 1773 John Roebuck, the owner of Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in Scotland, was forced into bankruptcy. At the time he owed Matthew Boulton over £1,200. Roebuck had been working very closely with the inventor, James Watt, who was developing a steam-engine that could power machinery. Boulton knew about Watt's research and wrote to him making an offer for Roebuck's share in the steam-engine. Roebuck refused but on 17th May, he changed his mind and accepted Boulton's terms. James Watt was also owed money by Roebuck, but as he had done a deal with his friend, he wrote a formal discharge "because I think the thousand pounds he (Boulton) he has paid more than the value of the property of the two thirds of the inventions." (18)

Roger Osborne, the author of Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013) has argued: "The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character.... Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm." (19)

Boulton pointed out that before he would give Watt financial backing, he insisted that the 1769 patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons. By 1775 the two men had their patent which gave them "the sole use and property of certain steam-engines of his invention, throughout the majesty's dominions." This prevented others from making steam-engines which contained improvements of their own. (20)

Under the terms of the partnership Watt assigned two-thirds of both property and the patent to Boulton. In return Boulton undertook to pay the expenses already incurred, to meet the costs of experiments, and to pay for materials and wages. The profits were to be divided in proportion to their shares. "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business." (21)

For the next eleven years Boulton's factory producing and selling Watt's steam-engines. These machines were mainly sold to colliery owners who used them to pump water from their mines. Watt's machine was very popular because it was four times more powerful than those that had been based on the Thomas Newcomen design. One of their machines was installed at Whitbread's Brewery in London in 1775 to grind malt and raise the liquor, taking the place of a huge wheel which needed six horses at a time to turn it. The company was very pleased with the economic benefits of Watt's steam engine that had cost them £1,000. (22)

Rotary-Motion Steam Engine

Watt continued to experiment and in 1781 he produced a rotary-motion steam engine. Whereas his earlier machine, with its up-and-down pumping action, was ideal for draining mines, this new steam engine could be used to drive many different types of machinery. Richard Arkwright was quick to importance of this new invention, and in 1783 he began using Watt's steam-engine in his textile factories. Others followed his lead and after fifteen years there were over 500 of Boulton & Watt's machines in Britain's mines and factories. (23)

The ironmaster John Wilkinson, was one of the first people to buy Watt's steam engine. He installed eleven engines at his Bradley ironworks by the 1790s and at least seven elsewhere. The partners depended heavily on Wilkinson for it was he who was capable of boring engine cylinders with greater accuracy than any other iron-founder. His boring machine has been called the first machine tool that was developed in the industrial revolution. (24)

Eric Hobsbawm has argued that James Watt's steam engine was "the foundation of industrial technology". (25) Arthur Young commented in his book, Tours in England and Wales (1791) about the impact that Watt had on Britain: "What trains of thought, what a spirit of exertion, what a mass and power of effort have sprung in every path of life, from the works of such men as Brindley, Watt, Priestley, Harrison, Arkwright.... In what path of life can a man be found that will not animate his pursuit from seeing the steam-engine of Watt?" (26)

Richard Guest pointed out that Watt's steam engine that drove the power looms was extremely popular with factory owners: "The increasing number of steam-looms is a certain proof of their superiority over the hand-looms. In 1818, there were in Manchester, Stockport, Middleton, Hyde, Stayley Bridge, and their vicinities, 14 factories, containing about 2,000 looms. In 1821, there were in the same neighbourhoods 32 factories, containing 5,732 looms. Since 1821, their number has still increased, and there are at present not less than 10,000 steam-looms at work in Great Britain." (27)

Boulton & Watt company had a virtual monopoly over the production of steam-engines. Watt charged his customers a premium for using his steam engines. To justify this he compared his machine to a horse. Watt calculated that a horse exerted a pull of 180 lb., therefore, when he made a machine, he described its power in relation to a horse, i.e. "a 20 horse-power engine". Watt worked out how much each company saved by using his machine rather than a team of horses. The company then had to pay him one third of this figure every year, for the next twenty-five years. (28)

Henry Brougham later recalled: "There was one quality, which most honourably distinguished him from too many inventors, and was worthy of all imitation, he was not only entirely free from jealously, but he exercised a careful and scrupulous self-denial, and was anxious not to appear, even by accident, as appropriating to himself that which he thought belonged to others." (29)

Manufacturing Coins

Boulton continued to produce other goods. In September 1778, Boulton commented "how far it may be prudent in me to stick to Engines or Buttons for I can consider Buttons as a sheet anchor". Jennifer Tann has argued: "It would be incorrect to stereotype Boulton as the entrepreneur and Watt as the inventor, for Boulton made many suggestions for improvements to the engine and Watt also had a good head for business. But there is no doubt that Boulton's flair for marketing was significant for the early success of the business." (30)

In 1786 Boulton applied steam power to coining machines. So successful was the process that as well as his supplying the home market, he produced coins for foreign governments as well. Boulton employed Jean-Pierre Droz from France and Conrad Heinrich Küchler from Germany in an attempt to improve the quality of coins. In 1789 Droz devised a collar used to engrave the sides of coins and ensure a circular shape. (31)

As his biographer has pointed out: "A mint to supply copper coinage to the government was established at Soho Manufactory. Towards the end of the eighteenth century Boulton undertook the supply of complete mints for overseas customers, the first one being the imperial mint in St Petersburg. Other orders followed and one of his last commissions before his death was the new Royal Mint in London. It was particularly for his mint interests that he sought out expert engravers and die-sinkers from continental Europe to enhance the level of skill at Soho Manufactory. By means of his mint machinery and the flow-production system in which it was deployed he achieved greater accuracy in the finished product." (32)

Slave-Trade

In 1787 Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and William Dillwyn established the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Other supporters were William Allen, John Wesley, Samuel Romilly, Thomas Walker, John Cartwright, James Ramsay, Charles Middleton, Henry Thornton and William Smith. Sharp was appointed as chairman. He accepted the title but never took the chair. Clarkson commented that Sharp "always seated himself at the lowest end of the room, choosing rather to serve the glorious cause in humility... than in the character of a distinguished individual." Clarkson was appointed secretary and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Samuel Hoare reported subscriptions of £136. (33)

Josiah Wedgwood joined the organising committee. As Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has pointed out: "Wedgwood asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands beseechingly." It included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" Hochschild goes onto argue that "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks, the image was an instant hit... Wedgwood's kneeling African, the equivalent of the label buttons we wear for electoral campaigns, was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause." (34)

Other members of the Lunar Society, including Matthew Boulton, Joseph Priestley, Thomas Day and Erasmus Darwin became involved in the campaign against the slave-trade. In 1789, along with Priestley, he joined the deputation to welcome Olaudah Equiano, who came to speak in Birmingham about his experiences as a slave and whose autobiography, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of America, was such a focus on the anti-slavery campaign. (35)

Boulton deeply felt the loss of some of his friends from the Lunar Society. A number of Boulton's friends died at the turn of the century. Josiah Wedgwood (1795), Joseph Black (1799), Erasmus Darwin (1802), Joseph Priestley (1804) and John Robison (1805). Boulton suffered from stones in the kidneys, and he told a friend: "My doctors say my only chance of continuing in this world depends on my living quiet in it." (36)

Matthew Boulton died of kidney failure at Soho House, Handsworth, on 17th August 1809. James Watt wrote that Boulton was "not only an ingenious mechanic, well skilled in all the practices of the Birmingham manufacturers, but possessed in a high degree the faculty of rendering any new invention of his own or others useful to the public, by organising and arranging the processes by which it could be carried on." (37) Watt died ten years later and was buried beside Boulton in St Mary's Church on 2nd September. (38)

Primary Sources

(1) Roger Osborne, Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution (2013)

When Watt visited Soho in early 1769, with a brand-new patent in his pocket, Boulton was already a major figure in British manufacturing. The two men instantly knew they could work together. Perhaps Watt saw that Boulton was the necessary complement to his own gloomy character - an energetic optimist who would carry him through his difficulties - while Boulton surely recognised the seriousness of Watt's character. When he returned to Glasgow Watt proposed to Roebuck that Boulton come in as a partner by buying one-third of the interest in the patent. Roebuck and Boulton already knew each other, having worked together on a plan to manufacture thermometers.

Watt was delighted not just by the prospect of investment hut especially by Boulton's personal enthusiasm. As he wrote soon after his return to Glasgow: "It gave me great joy when you seemed to think so favourably of our scheme as to wish to engage in it." Boulton on the other hand was both excited about the project and in need of money - the building of Soho had nearly ruined him and he was often better at spending than making money.

(2) Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007)

To take out his patent, Watt had had to go down to London in 1769 to argue his case and on the way he had called to see the Birmingham "toy" maker Matthew Boulton at his Soho works. For many of the ingenious processes he had devised to turn out buckles, buttons and a huge variety of metal pieces, Boulton relied on machines powered by a waterwheel. He had tried a Savery engine but it did not work efficiently.Watt and Boulton got on well at their first meeting and it was to Birmingham that Watt returned when Roebuck could no longer fund him. As it happened, one of Roebuck's creditors was Boulton, who agreed to take over the two-thirds share of Watt's patent. The Watt family then moved lock, stock and barrel to Birmingham along with the various parts of the revolutionary engine.

Before he would give Watt financial backing, however, Boulton insisted that the patent, with only eight years to run, should be extended to twenty-five years. This meant petitioning the House of Commons and beating off the opposition of rival engineers. By 1775 the two men had their patent, valid until 1800, and Watt was well on the way to perfecting his steam engine. As luck would have it, just when Watt needed a very accurately bored cylinder for his separate condenser, "Iron Mad" Wilkinson had perfected his cannon boring machine and was able to produce these crucial components for the new engines. The large boilers were made elsewhere in the Midlands, while Boulton's own workshops could turn out most of the smaller working parts.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)