Mary Sophia Allen

Mary Sophia Allen, the daughter of the manager of the Great Western Railway, was born in Cardiff on 12th March, 1878. Educated at Princess Helena College in Ealing, she joined the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU) after meeting Annie Kenney. Her father gave her an ultimatum to either give up her involvement in the suffragette movement or to leave the house. She left but her father continued to support her financially.

In February 1909 she was a member of the WSPU deputation to the House of Commons. She was one of the 28 women arrested and was sentenced to a month's imprisonment in Holloway. On her release she was appointed as WSPU organiser in Cardiff.

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. This included Mary Allen.

Marion Wallace-Dunlop was a fellow prisoner. Christabel Pankhurst later reported: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded." She refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes, including Mary Allen, adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike.

In August 1909 she received a hunger-strike medal from Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), she was the first woman to be awarded this medal. In November 1909 she was arrested for breaking the windows of the Bristol Liberal Club during a visit made by Winston Churchill. She was sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment and after going on hunger strike she was forcibly fed.

Grace Roe remarked that at this time Mary Allen was "very feminine, very delicate". Mary Allen recalled that her digestion had been permanently affected and she was forbidden by Emmeline Pankhurst to take part in any further militant activity.

In February 1912 she became organizer of the Hastings branch of the WSPU and in early 1914 she replaced Lucy Burns as organizer in Edinburgh. On 6th May Christabel Pankhurst wrote to Janie Allan that "in Edinburgh a small handful of people... are decidedly cantankerous, and the person who is organising for the time being is made to feel the effect of this. These people criticise Miss Mary Allen."

Like most members of the WSPU, Allen agreed to the decision to give full support to the British war effort during the First World War. According to Joan Lock, the author of The British Policewoman (1979): "She (Mary Allen) was invited to join a needlework guild, a prospect which filled her with horror: she wanted action. While in this state of limbo, she overheard two people on a bus discussing the risible idea of women police. Mary was enchanted by the notion and immediately investigated and volunteered.

In September 1914, Nina Boyle founded the Women Police Volunteers. The following year Margaret Damer Dawson became Commandant and Allen became Sub-Commandant. Allen argued that it was her experience in the WSPU that made her realise how necessary it was that women when arrested should not "be handled by men."

The government had always opposed the idea of police women but with large numbers of policemen joining the British Army, it was considered a good idea to have women volunteers to help run the service. Another reason that Dawson's proposal was accepted was that her members were willing to work without pay.

Allen later remarked in her book, The Pioneer Policewoman, that: "A sense of humour had kept me from any bitterness. I was quite as enthusiastically ready to work with and for the police as I had been prepared, if necessary, to enter into combat with them."

In February 1915 Allen and Margaret Damer Dawson renamed her organisation, the Women's Police Service (WPS). At first the WPS concentrated its work in the London area. Wearing a dark-blue uniform, the WPS were assigned responsibilities such as looking after the welfare of refugees. Later that year, Allen was sent to sort out problems in Grantham and Hull. Both towns had army camps and local people were complaining about drunken behaviour and a growth in prostitution.

According to Rebecca Jennings, the author of A Lesbian History of Britain (2007): "Mary Allen's enthusiasm was shared by Margaret Damer Dawson, and the two soon established a close professional and personal relationship, living together in London between 1914 and 1920."

When the Armistice was signed, there were 357 members of the Women's Police Service. Margaret Damer Dawson and Allen, asked the Chief Commissioner, Sir Nevil Macready, to make them a permanent part of his force. He refused, saying that the women were "too educated" and would "irritate" male members of the force. Macready instead decided to recruit and train his own women. However, both Dawson and Allen were awarded the OBE for services to their country during wartime.

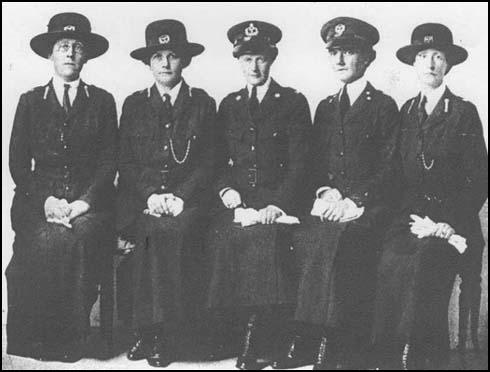

When ill-health forced Margaret Damer Dawson to retire in 1920, Allen became the new Commandant of the Women Police Service. In February, 1920, Mary Allen and four of her members were charged with "impersonating police officers". It was claimed that their uniforms were too similar to that of the one worn by the Metropolitan Women Police Patrols. After a four-day hearing Macready won his case and the WPS were forced to change its uniform and its name to the Women's Auxiliary Service.

Rebecca Jennings has argued that: "When Dawson died in 1920, Allen was a major beneficiary in her will, continuing to live in Dawson's house, Danehill, throughout the 1930s and beginning a relationship in the early 1920s with another former WPS officer Miss Helen Tagart."

In 1922 Allen spent time in Cologne where she trained German women for police work. During the 1926 General Strike she helped to keep the road transport services running. According to her biographer, Vera Di Campli San Vito: "In 1927 she founded and edited the Policewoman's Review, which ran until 1937. It was here, in December 1933, that she advertised for recruits to her newly formed women's reserve, the object of which was to train women for service in any national emergency."

Allen was a frequent visitor to Nazi Germany and after meeting Adolf Hitler in 1934 and became one of his most fervent admirers. In a discussion with Hermann Goering she was very pleased when he said that policewomen should wear uniform. Even when on official duties with the Women's Auxiliary Service she wore Nazi style jack-boots.

Allen was an active supporter of General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist Army during the Spanish Civil War. She was also Chief Women's Officer of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) and a member of the the Right-Club. The historian, Julie V. Gottlieb, has argued: "Allen was a prominent supporter of Mosley's British Union, a movement she claimed she had joined due to her sympathy for its anti-war policy." In 1940 she contributed a series of articles for Action, the organ of the BUF.

Her extreme right-wing views made her unpopular with some members of the Women's Auxiliary Service and she was forced to leave the movement with the approach of the Second World War. According to Helena Wojtczak: "Mary Allen became increasingly eccentric, and her apparent support for Hitler and Goering led to questions about whether she should be interned in 1940." Although she was not interned, her membership of the British Union of Fascists resulted in a suspension order under defence regulation 18B on 11th July 1940.

Mary Allen, who wrote several books, including The Pioneer Policewoman (1925), Woman at the Crossroads (1934) and Lady in Blue (1936), died in the Birdhurst Nursing Home, 4 Birdhurst Road, Croydon, of cerebral thrombosis and cerebral arteriosclerosis on 16th December 1964.

Primary Sources

(1) Joan Lock, The British Policewoman (1979)

She (Mary Allen) was invited to join a needlework guild, a prospect which filled her with horror: she wanted action. While in this state of limbo, she overheard two people on a bus discussing the risible idea of women police. Mary was enchanted by the notion and immediately investigated and volunteered.

(2) Rebecca Jennings, A Lesbian History of Britain (2007)

A number of voluntary women police organisations were also established by middle and upper-class women, as an extension of the growing involvement of such women in social welfare and factory inspection work. At the outbreak of war, the feminist National Union of Working Women (NUWW) proposed a force of non-uniformed volunteer patrols, while a number of women from a more militant Suffragette background, including Margaret Damer Dawson and Nina Boyle, established the uniformed professional Women's Police Volunteers (WPV). When a disagreement over the role of the WPV occurred soon afterwards, Margaret Damer Dawson and Mary Allen broke with Nina Boyle and established a further group, the Women Police Service (WPS). The central role of women police during the war was the policing and protection of women, with a focus on moral welfare work, in the context of widespread anxieties about female promiscuity. Women police patrolled parks, the perimeters of garrisons and other public spaces, separating men and women who were thought to be engaging in immoral or inappropriate behaviour and following suspect couples to prevent illicit sexual encounters. Continuing a practice of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century moral purity groups, women police also entered public houses and other sites of "ill-repute". By 1916, the WPS were also heavily involved in patrolling and inspecting munitions factories where women were employed, to ensure the moral conduct of the women factory workers.

Many of the early women police recruits were from the educated middle class and were drawn into the work through their involvement in feminist politics before the war. Both Nina Boyle and Mary Allen had been members of the militant suffrage group the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the WPS maintained a strong feminist outlook, campaigning for an independent professional women's police force with equal powers to policemen....

Mary Allen's enthusiasm was shared by Margaret Damer Dawson, and the two soon established a close professional and personal relationship, living together in London between 1914 and 1920. When Dawson died in 1920, Allen was a major beneficiary in her will, continuing to live in Dawson's house, Danehill, throughout the 1930s and beginning a relationship in the early 1920s with another former WPS officer Miss Helen Tagart.

(3) In her autobiography, The Pioneer Policewoman, Mary Allen recalled the actions of one policewoman in a London tube station during the war.

A soldier (who had just returned from the Western Front) was so disordered while he was going down the stairs into the tube station, he became suddenly aware of the crowds of people coming up, he looked haggardly about, and evidently mistaking the hollow space below for the trenches and the ascending crowd for Germans, fixed his bayonet and charged. But for the women constable on duty at the turn of the staircase, who was quick enough to divine his trouble and hang on to him with all her strength to prevent his forward advance, he would have wounded many and caused danger and panic.

(4) Mrs. Creighton, Voluntary Patrol Committee, Annual General Meeting (1917)

The policewoman of the future will be taken from that class of women who are forced to earn their living by it, and not so much from the educated women who now take smaller or no pay for the sake of helping.

(5) Eveline W. Brainerd, The Outlook (10th September, 1924)

The proposal of the New York Women's Police Bureau to train college women for policework, though a new idea here, has had ten years' trial in England and has proved its worth. The head of the Women's Auxiliary Service for training women candidates for police service in Great Britain, Mary E. Allen, came to this country last spring to study our police systems and to speak on the business of the women constables as worked out in Great Britain.

No one in London would turn to gaze after the trim uniform of the Commandant, but here the visored cap, the high-collared shirtwaist and black tie, the trousers and full-skirted coat meeting the tops of the black boots, catch every eye. When the Commandant is caught with her cap off there is another surprise, for the heavy hair is close cropped -- not bobbed, notice. It frames a strong, kindly face, of a type seen more often in England than among the descendants of the settlers on this side of the river. One would not choose to have the steady eyes rest upon one at an untoward moment, but at the corners are humorous wrinkles that show she has never become obsessed by the sordid and tragic scenes known to the police.

The war conditions brought to sudden action in 1914 the plans for an experiment in women on the police force that had long been considered by a group of thoughtful Englishwomen whose social work had shown them the need for some more understanding and careful treatment of women and children than the police force as constituted could give. In that time of need their offer, as a private organization, to train women for appointment to the regular police force was readily accepted. Commandant Allen was one of these women. She herself served on the police force at Grantham, where the experiment was first tried out, and, having learned the job, working side by side with the "Bobbies," she became head of the training school for these new officers, who during the war numbered a thousand, and who are now to be found on the local staffs in various parts of England and Scotland, and in the occupied territory in Germany.