Michael Gold

Itzok Isaac Granich, the son of Jewish immigrants, was born in New York City on 12th April, 1893. He later took the name, Michael Gold. His family lived on the Lower East Side of the city.

Gold's brother, Manny, was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World and he was introduced into the world of socialism at a very early age. He attended journalism classes at New York City University (1912-13) and spent a year as a special student at Harvard in 1914.

Gold returned to New York City and began to associate with a group of socialists that lived in Greenwich Village. This included Max Eastman, John Reed, Floyd Dell, Robert Minor, Art Young, Arturo Giovannitti and Boardman Robinson. He also became a regular contributor to the socialist journal, The Masses and the New York Call.

A group of left-wing writers including Gold, Floyd Dell, John Reed, George Jig Cook, Mary Heaton Vorse, Michael Gold, Susan Glaspell, Hutchins Hapgood, Harry Kemp, Theodore Dreiser, William Zorach, Neith Boyce and Louise Bryant, often spent their summers in Provincetown. In 1915 several members of the group established the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf was turned into a theatre. Later, other writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay joined the group. Gold's first one-act play was performed in 1916. Over the next three years he had two more plays performed by the Provincetown Players.

Michael Gold, like most of the people who wrote for The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in the fact that the articles and cartoons that appeared in journal attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges.

In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of Dell and his fellow defendants.

In 1918 Max Eastman joined with Art Young, Floyd Dell and his sister, Crystal Eastman, to establish another radical journal, The Liberator. Other writers and artists involved in the magazine included Michael Gold, Claude McKay, Boardman Robinson, Roger Baldwin, Louis Fraina, Norman Thomas, John Reed, Louise Bryant, Bertrand Russell, Dorothy Day, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, Maurice Becker, Helen Keller, Cornelia Barns, Louis Untermeyer, Hugo Gellert, K. R. Chamberlain and William Gropper.

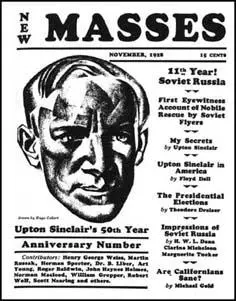

In 1920 Michael Gold was appointed editor of the journal. Two years later the the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the American Communist Party and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. Many of the people who contributed to the The Masses and the original The Liberator, were unhappy with this development and in 1926, they started their own journal, the New Masses. Michael Gold was once again appointed as editor.

Gold joined forces with John Dos Passos, John Howard Lawson, Francis Edward Faragoh and Emjo Basshe to establish their own 52nd Street Theatre that was sponsored by Otto Hermann Kahn. On 14th March, 1927, Time Magazine reported: "Here, at old Bim's, now the 52nd Street Theatre, they propose to experiment with those radical dramatic forms of whose marketability the commercial producers are suspicious."

According to Dan Georgakas: "His (Gold) period of greatest literary influence would be from the founding of the New Masses until the mid-1930s, a time when he was identified as the leading American advocate of proletarian literature." In 1930 he published his first novel, Jews Without Money. Georgakas argues that: "In addition to the work's considerable intrinsic merits, its appearance coincided with the deepening of a depression that made a novel about poverty pertinent to a mass audience. Friends hailed him as the American Gorky, but Gold was never to fulfill his promise as a writer of fiction." In fact, his first novel was also his last.

As editor of New Masses Gold allowed it to become a strong supporter of the Soviet Union. Writers such as Max Eastman and Floyd Dell, who were not members of the American Communist Party, ceased to become involved in the journal. Gold produced a visually exciting journal by employing artists such as William Gropper, Art Young, Hugo Gellert and Reginald Marsh. By 1935 sales had reached 25,000.

According to David Peck: "The New Masses sponsored some of the decade's most important literary organizations (the John Reed Clubs in the early thirties, the first American Writers and Artists Congresses in 1935), provoked some of its most controversial literary discussions (on proletarian literature and Marxist literary criticism), and published some of the best radical literature to come out of the thirties (the reportage of Meridel Le Suer, John L. Spivak, Josephine Herbst, and Agnes Smedley)."

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the New Masses was a strong supporter of the Popular Front government and tended to concentrate on the growing fascist threat and in order to achieve left-wing unity was far less critical of liberals and other non-communists.

In 1933 Michael Gold became a columnist for the Daily Worker in 1933, the journal of the American Communist Party, a role he would retain until the end of his life. Gold followed the party line and was ordered to attack those like Max Eastman, who had become a follower of Leon Trotsky after Joseph Stalin had ordered the Great Purge. Others who suffered from Gold's criticism included Ernest Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, Waldo Frank, Albert Maltz, Sherwood Anderson, Robinson Jeffers and Granville Hicks. A collection of these literary reviews were published in The Hollow Men (1941).

Michael Gold continued to defend the policies of the Soviet Union, including sending in the Red Army to put down the Hungarian Uprising, until his death in Terra Linda, on 14th May, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Time Magazine (14th March, 1927)

The New Playwrights - John Dos Passos, John Howard Lawson, Francis Faragoh., Michael Gold, Em Jo Basshe - impatient with the restraint of conventional theatre, have set up one of their own, bolstered up by the generous purse of Otto Hermann Kahn. Here, at old Bim's, now the 52nd Street Theatre, they propose to experiment with those radical dramatic forms of whose marketability the commercial producers are suspicious.

Their first production, Loud Speaker, was written by John Howard Lawson, author of Processional ). As expected, it is staged against a "constructivist" background and presents the subjective state of the principal characters as well as their objective actions. The virtue of such staging is that, by affording the playwright several planes of action on one stage, it allows greater flexibility than is permitted by the rigid three-walled limitations of ordinary theatre. Thus, in Loud Speaker, the candidate for governor of the State may be discovered mulling over his radio speech in one corner of the stage, while his memory of an Atlantic City bathing beauty may be enacted in another corner. His daughter may black-bottom on an upper level and his wife receive a weird, bearded, hypnotic lover on still another. By proper punctuation and emphasis, such a production may be made colorful, clear, rapid, nervous, like jazz music. But, though the new playwrights deserve credit for the enterprise, Mr. Lawson's "farce" fails to enthrall the observer, because: 1) The lines are not pointed artfully enough to evoke laughs in the right places. 2) His characters are not sufficiently personalized. No one cares whether the candidate for Governor does get drunk and say the wrong things over the radio, thus confounding the tabloids and winning the election by unorthodox strategy.

(2) Time Magazine (24th February, 1930)

Not all Jews have money; some, like Author Gold's family, live in the slums, are too poor ever to get away. Says Author Gold: "Bedbugs are what people mean when they say: Poverty. There are enough pleasant superficial liars writing in America. I will write a truthful book of Poverty; I will mention bedbugs."

Gold's parents came from Rumania to a Manhattan East Side tenement in Chrystie Street. They were orthodox Jews, decent, kindly people, believed in dybbuks (evil spirits). Manhattan tenement life shocked their kindliness and decency, did not shake their faith in evil spirits. Chrystie Street was in the red-light district, under the protection of Tammany Hall. Mike Gold never forgot his fifth birthday, for that night two gunmen shot it out in the back yard.

Mike and his gang played in vacant lots when they could, but mostly in the street. Once one of them was attacked by a pervert. Mike's little sister was killed by a truck.

Father Gold was a housepainter, until he fell from a scaffold and broke all the bones in his feet. He was also a wonderful storyteller: some of his tales took weeks to finish. Mike discovered afterward that they came from the Arabian Nights: his father had heard them in Oriental marketplaces, from Turkish or Rumanian peasants. Once his father tried voting. He was taken by a Jewish Tammany man to the polls, voted three times, was suddenly hit over the head with a blackjack. Groaned he to his wife: "Katie, you were right. Voting is only for Irish bums. Never again will I do such a dangerous thing."

Gyp the Blood, famed killer of Gambler Rosenthal, was in Mike's public school class. Some of Mike's pals grew up to be rich; one of them became a gunman. Mike ends his own story at the point where he tired of selling papers and began to look for a job - not because he wanted to be rich (he hated capitalism) but to stay alive.

Forty times he has been chased by cops for taking part in street demonstrations; 20 strikes have had his help. In Boston he became an anarchist; Mexico converted him to Communism. One time editorial assistant to Max Eastman of the late great Masses, three years ago he became editor of the only artistic-radical magazine left in the U. S., the New Masses, in which Jews Without Money appeared serially. He has had two plays produced: Hoboken Blues, Fiesta. Says he: "Both were flops." He has also written 120 Million. He is on the board of the New Playwrights' Theatre supported by Capitalist Otto H. Kahn. Last February the New Playwrights gave a dinner, invited Maecenas Kahn, made many speeches attacking capitalism, prophesying the triumph of the workers. Banker Kahn, bland, smiling, replied in the best speech of the evening. Intimated he: I give my money gladly to artistic experiments, am willing to take a chance on thereby upsetting the social order.