Emergency Banking Relief Act

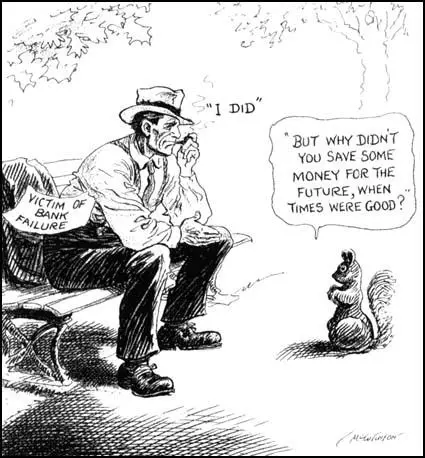

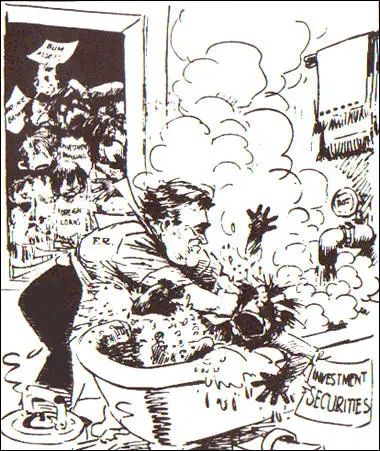

The economic depression in the early 1930s had a disastrous impact on the banking system in America. Private banks which had invested in stocks and shares found that the Wall Street Crash had severely reduced their funds.

In December, 1930, the Bank of the United States, with more than 410 branches in California and more than a million depositors, was forced to close. (1) According to David M. Kennedy the closing of this one bank another "two hundred smaller banks closed because of the deposits in that bank from the others." (2)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office on 4th March, 1933. His first act as president was to deal with the country's banking crisis. Since the beginning of the depression, a fifth of all banks had been forced to close. Already 389 banks had shut their doors since the beginning of the year. As a consequence, around 15% of people's life-savings had been lost. Banking was at the point of collapse. In 47 of the 48 states banks were either closed or working under tight restrictions. To buy time to seek a solution Roosevelt declared a four-day bank holiday. It has been claimed that the term "bank holiday" was used to seem festive and liberating. "The real point - the account holders could not use their money or get credit - was obscured." (3)

Roosevelt's advisers, Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter, and Rexford G. Tugwell agreed with progressives who wanted to use this opportunity to establish a truly national banking system. Heads of great financial institutions opposed this idea. Louis Howe supported conservatives on the Brains Trust such as Raymond Moley and Adolf Berle, who feared such a measure would create very dangerous enemies. Roosevelt was worried that such action "might accentuate the national sense of panic and bewilderment". (4)

Roosevelt summoned Congress into special session and presented it with an emergency banking bill that permitted the government to reopen the banks it ascertained to be sound, and other such banks as rapidly, as possible." The statue passed the House of Representatives by acclamation in a voice vote in forty minutes. In the Senate there was some debate and seven progressives, Robert LaFollette Jr, Huey P. Long, Gerald Nye, Edward Costigan, Henrik Shipstead, Porter Dale and Robert Davis Carey, voted against as they believed that it did not go far enough in asserting federal control. (5)

On 9th March, 1933, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Relief Act. Within three days, 5,000 banks had been given permission to be re-opened. President Roosevelt gave the first of his radio broadcasts (later known as his "fireside chats"): "Some of our bankers have shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people's funds. They had used money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was, of course, not true of the vast majority of our banks, but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity. It was the government's job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible. And the job is being performed. Confidence and courage are the essentials in our plan. We must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumours. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. Together we cannot fail." (6)

Will Rogers welcomed the speech: "Mr. Roosevelt stepped to the microphone last night and knocked another home run. His message was not only a great comfort to the people, but it pointed a lesson to all radio announcers and public speakers what to do with a big vocabulary - leave it at home in the dictionary. Our President took such a dry subject as banking (and when I say dry, I mean dry, for if it had been liquid, he wouldn't have to speak on it at all) and made everybody understand it, even the bankers." (7)

Marriner Eccles was appointed as Governor of the Federal Reserve Board in November, 1934. The following year Eccles and Lauchlin Currie drafted a new banking bill to secure radical reform of the central bank for the first time since the formation of the Federal Reserve Board in 1913. It emphasized budget deficits as a way out of the Great Depression and it was fiercely resisted by bankers and the conservatives in the Senate. The banker, James P. Warburg commented that the bill was: "Curried Keynes... a large, half-cooked lump of J. Maynard Keynes... liberally seasoned with a sauce prepared by professor Lauchlin Currie." (8)

With strong support from California bankers eager to undermine New York City domination of national banking, the 1935 Banking Act was passed by Congress. Over the next few years Eccles joined Harry Hopkins, Harold Ickes, Frances Perkins and Henry A. Wallace to continue increased government spending whereas Henry Morgenthau, James Farley and Daniel C. Roper urged President Roosevelt to balance the budget. (9)

Primary Sources

(1) David M. Kennedy, interviewed by Studs Terkel, in his book, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970)

All through the Twenties, they were having about six hundred banks a year close. In 1929 and 1930 they got into thousands. Closing every day. There was one bank in New York, the Bank of the United States - in the wake of that closing, two hundred smaller banks closed because of the deposits in that bank from the others.

(2) Ruth McKenney, diary entries (26th February - 4th March, 1933)

26th February: Horrible rumours spread through West Hill. Bank officials didn't show up at church services and weren't home at one o'clock to eat the usual big Sunday dinner with their families.

27th February: The Akron banks went on a "restricted withdrawal basis". The lobby of the First-Central Trust Company was a madhouse. Bewildered grocery store owners and frantic housewives stood in line with their passbooks shrilly demanding their money. Soft-voiced clerks explained, over and over, that "everything was all right".

Ist March: The local newspapers spread great cheer over the local banking situation. Pay rolls were said to be passing through the bank, taxes were being paid, business places were finding their operations unhampered.

3rd March: In the nearby empty streetcars, men told scare stories. Hysterical women wept on neighbours' shoulders, "Everything we had is gone. Now we go on relief."

4th March: At nine, the First-Central Trust Company owned for business. The lobby was jammed. Clerks paid out the one per cent allowed. "I didn't get paid this week," men in work clothes shouted. "You've got to give me some of my money." "No!" said the clerks, signalling for the bank guards. At noon the bank guards hustled the crowd out. "Closing time," they shouted.

(3) Newsweek Magazine (11th March, 1933)

Less than 34 hours after he became President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt took action unprecedented in American history. By proclamation, under a war-time measure's terms, he closed the doors of every bank in the United States and its possessions.

(4) Franklin D. Roosevelt, radio broadcast, Fireside Chat (12th March, 1933)

Some of our bankers have shown themselves either incompetent or dishonest in their handling of the people's funds. They had used money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was, of course, not true of the vast majority of our banks, but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity. It was the government's job to straighten out this situation and do it as quickly as possible. And the job is being performed. Confidence and courage are the essentials in our plan. We must have faith; you must not be stampeded by rumours. We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. Together we cannot fail.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject