Martin Luther

Martin Luther, the eldest son of Hans Luther, was born in Eisleben, Saxony on 10th November 1483. His father worked in the copper-refining business and the family moved to Mansfeld.

It was claimed that Hans Luther "belonged to that group of struggling but upwardly mobile working class people". His prospects were improved when he married Margaretta Lindemann who came from a family where for generations they had been doctors, lawyers and teachers. (1)

Martin Luther went to the local school in Magdeburg where "he received a thorough training in the Latin language and learned by rote the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, and morning and evening prayers". (2)

Luther's parents were religious but also superstitious. When one of her infant children died, Margaretta Luther did not attribute the tragedy to the will of God or seek within herself the reason for divine judgement. Instead she accused one of her neighbours of witchcraft. Martin was brought up believing that "one should wear charms, recite incantations, sprinkle the hearth with holy water and employ such other resources as the Church provided to ward off their attacks." (3)

In 1501 Martin Luther went to University of Erfurt. He seems to have disliked the experience and complained about the "rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises" and later described it as a "beerhouse and whorehouse". (4) Luther proved himself to be a gifted scholar and he was given the nickname "the philosopher".

Martin Luther graduated in July, 1505. According to his biographer, Derek Wilson: "He felt justifiable satisfaction when he qualified for his master's degree, coming second out of a class of seventeen, and it gave him immense pleasure to witness his parents' pride when they came to Erfurt to watch him go in torchlight procession to receive his new honour." (5)

In 1512 Martin Luther entered the monastery in Erfurt of the Order of the Hermits of St. Augustine. According to Owen Chadwick, he was "an earnest friar, practising the prayers and fasts with zeal". However, he found it difficult to keep to the rules of the monastery. Luther later recalled: "I tried as hard as I could to keep the Rule. I used to be contrite, and make a list of my sins. I confessed them again and again. I scrupulously carried out the penances which were allotted to me. And yet my conscience kept nagging... I was trying to cure the doubts and scruples of the conscience with human remedies, the traditions of men. The more I tried these remedies, the tradition of men. The more I tried these remedies, the more troubled and uneasy my conscience grew." (6)

Hans Luther was angry with him for abandoning what should have been a lucrative career in law in favour of the monastery. "His spartan quarters consisted of an unheated cell furnished only with a table and chair. His daily activities were structured around the monastic rule and the observance of the canonical hours, which began at 2:00 in the morning. In the fall of 1506, he was fully admitted to the order and began to prepare for his ordination to the priesthood. He celebrated his first mass in May 1507 with a great deal of fear and trembling, according to his own recollection." (7)

Some historians have questioned Martin Luther's later account of his time in the monastery where he claimed that "I alone in the Erfurt monastery read the Bible." Henry Ganss points out that the Augustinian rule lays especial stress on the monition that the novice "read the Scripture assiduously, hear it devoutly, and learn it fervently". Ganss goes on to argue: "There is no reason to doubt that Luther's monastic career thus far was exemplary, tranquil, happy; his heart at rest, his mind undisturbed, his soul at peace." (8)

Ninety-five Theses

In 1508 Martin Luther began studying at the newly founded University of Wittenberg. He was awarded his Doctor of Theology on 21st October 1512 and was appointed to the post of professor in biblical studies. He also began to publish theological writings. Luther was considered to be a good teacher. One of his students commented that he was "a man of middle stature, with a voice that combined sharpness in the enunciation of syllables and words, and softness in tone. He spoke neither too quickly nor too slowly, but at an even pace, without hesitation and very clearly." (9)

Luther began to question traditional Catholic teaching. This included the theology of humility (whereby confession of one's own utter sinfulness is all that God asks) and the theology of justification by faith (in which human beings are seen as incapable of any turning towards God by their own efforts). (10)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar arrived in Wittenberg. He was selling documents called indulgences that pardoned people for the sins they had committed. Tetzel told people that the money raised by the sale of these indulgences would be used to repair St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Luther was very angry that Pope Leo X was raising money in this way. He believed that it was wrong for people to be able to buy forgiveness for sins they had committed. Luther wrote a letter to the Bishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. (11)

On 31st October, 1517, Martin Luther affixed to the castle church door, which served as the "black-board" of the university, on which all notices of disputations and high academic functions were displayed, his Ninety-five Theses. The same day he sent a copy of the Theses to the professors of the University of Mainz. They immediately agreed that they were "heretical". (12) For example, Thesis 86, asks: "Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?" (13)

As Hans J. Hillerbrand has pointed out: "By the end of 1518, according to most scholars, Luther had reached a new understanding of the pivotal Christian notion of salvation, or reconciliation with God. Over the centuries the church had conceived the means of salvation in a variety of ways, but common to all of them was the idea that salvation is jointly effected by humans and by God - by humans through marshalling their will to do good works and thereby to please God, and by God through his offer of forgiving grace. Luther broke dramatically with this tradition by asserting that humans can contribute nothing to their salvation: salvation is, fully and completely, a work of divine grace." (14)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Pope Leo X ordered Luther to stop stirring up trouble. This attempt to keep Luther quiet had the opposite effect. Luther now started issuing statements about other issues. For example, at that time people believed that the Pope was infallible (incapable of error). However, Luther was convinced that Leo X was wrong to sell indulgences. Therefore, Luther argued, the Pope could not possibly be infallible.

During the next year Martin Luther wrote a number of tracts criticising the Papal indulgences, the doctrine of Purgatory, and the corruptions of the Church. "He had launched a national movement in Germany, supported by princes and peasants alike, against the Pope, the Church of Rome, and its economic exploitation of the German people." (15)

Johann Tetzel published a response to Luther's tracts. Tetzel's Theses opposed all of Luther's suggested reforms. Henry Ganss has admitted that it was probably a mistake to give Tetzel this task. "It must be admitted that they at times gave an uncompromising, even dogmatic, sanction to mere theological opinions, that were hardly consonant with the most accurate scholarship. At Wittenberg the created wild excitement, and an unfortunate hawker who offered them for sale, was mobbed by the students, and his stock of about eight hundred copies publicly burned in the market square - a proceeding that met with Luther's disapproval." (16)

In 1520 Martin Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation. In the tract he argued that the clergy were unable or unwilling to reform the Church. He suggested the kings and princes must step in and carry out this task. Luther went on to claim that reform is impossible unless the Pope's power in Germany is destroyed. He urged them to bring an end to the rule of clerical celibacy and the selling of indulgences. "The German nation and empire must be freed to live their own lives. The princes must make laws for the moral reform of the people, restraining extravagance in dress or feasts or spices, destroying the public brothels, controlling the bankers and credit." (17)

Humanists like Desiderius Erasmus had criticised the Catholic Church but Luther's attack was very different. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "From the beginning there was a fundamental difference between Erasmus and Luther, between the humanists and the Lutherans. The humanists wished to remove the corruptions and to reform the Church in order to strengthen it; the Lutherans, almost from the beginning, wished to overthrow the Church, believing that it had become incurably wicked and was not the Church of Christ on earth." (18)

On 15th June 1520, Pope Leo X issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against the Pope. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!" (19)

Emperor Charles V

Martin Luther was protected by Frederick III of Saxony. Pressure was placed on Emperor Charles V by the Pope to deal with Luther. Charles responded by claiming: "I am born of the most Christian emperors of the noble German nation, of the Catholic kings of Spain, the archdukes of Austria, the dukes of Burgundy, who were all to the death true sons of the Roman church, defenders of the Catholic faith, of the sacred customs, decrees and usages of its worship... Therefore I am determined to set my kingdoms and dominions, my friends, my body, my blood, my life, my soul upon the unity of the Church and the purity of the faith." (20)

Charles V was totally opposed to the ideas of Martin Luther and it is reported that when he was presented with a copy of To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation he tore it up in a rage. However, he was in a difficult position. As Derek Wilson has pointed out: "In most of his rag-bag of territories Charles ruled by right of inheritance but in Germany he held the crown by consent of the electors, chief among whom was Frederick of Saxony." (21)

The twenty-year old Emperor Charles invited Martin Luther to meet him in the city of Worms. On 18th April 1521, Charles asked Luther if he was willing to recant. He replied: "Unless I am proved wrong by Scriptures or by evident reason, then I am a prisoner in conscience to the Word of God. I cannot retract and I will not retract. To go against the conscience is neither safe nor right. God help me." (22)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey suggested to Henry VIII that he might want to distinguish himself from other European princes by showing himself to be erudite as well as a supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. With the help of Wolsey and Thomas More, Henry composed a reply to Martin Luther entitled In Defence of the Seven Sacraments. (23) Pope Leo X was delighted with the document and in 1521 he granted him the title, Defender of the Faith. Luther responded by denouncing Henry as the "king of lies" and a "damnable and rotten worm". As Peter Ackroyd has pointed out: "Henry was never warmly disposed towards Lutherism and, in most respects, remained an orthodox Catholic." (24)

Martin Luther had such a strong following in Germany the Emperor was reluctant to call for his arrest. Instead he was declared an outlaw. Luther returned to the protection of Frederick III of Saxony who had no intention of surrendering him to the Catholic authorities to be burnt or hanged. Luther went to live in Wartburg Castle where he began to translate the New Testament into German. (25)

There had been German versions of the Bible for nearly 50 years but they were of poor quality and were considered unreadable. Luther faced the basic problem of every translator: that of converting the original into the idioms and thought patterns of his own day. Luther's first version of the New Testament was published in September, 1522. It was immediately banned and people faced the possibility of arrest, imprisonment and death by owning, reading and selling copies of Luther's Bible. (26)

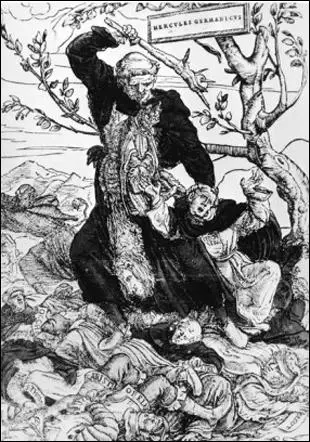

Hans Holbein was commissioned to create an image of Martin Luther. Published in 1523 it depicted Luther as the Greek super-hero and god, Hercules, attacking people with a viciously spiked club. In the picture, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, Duns Scotus and Nicholas of Lyra already lay bludgeoned to death at his feet and the German inquisitor, Jacob van Hoogstraaten was about to receive his fatal stroke. Suspended from a ring in Luther's nose was the figure of Pope Leo X. (27)

The author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "What was clever about this print (and what has made it difficult for later ages to determine its true message) was that it was capable of various interpretations. Followers of Luther could see their champion represented as a truly god-like being of awesome power, the agent of divine vengeance. Classical scholars, delighting in the many subtle allusions (such as the representation of the triple-tiaraed pope as the three-bodied monster, Geryon) could applaud the vivid representation of Luther as the champion of falsehood over medieval error. Yet, papalists could look on the same image and see in it a vindication of Leo's description of the uncouth German as the destructive wild boar in the vineyard and, for this reason, the engraving received a very mixed reception in Wittenberg." (28)

Influence of Luther's ideas in England

Martin Luther's ideas had a major impact on young men studying to be priests. Students at Cambridge University would meet at the White Horse tavern. It was nicknamed "Little Germany" as the Lutheran creed was discussed within its walls, and the participants were known as "Germans". Those involved in the debates about religious reform included Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Shaxton and Matthew Parker. These students also went to hear the sermons of preachers such as Robert Barnes and Thomas Bilney. (29)

If the Pope could be wrong about indulgences, Luther argued he could be wrong about other things. For hundreds of years popes had only allowed bibles to be printed in Latin or Greek. Luther pointed out that only a minority of people in Germany could read these languages. Therefore to find out what was in the Bible they had to rely on priests who could read and speak Latin or Greek. Luther, on the other hand, wanted people to read the Bible for themselves.

Luther also began work on what proved to be one of his foremost achievements - the translation of the New Testament into the German vernacular. "This task was an obvious ramification of his insistence that the Bible alone is the source of Christian truth and his related belief that everyone is capable of understanding the biblical message. Luther’s translation profoundly affected the development of the written German language. The precedent he set was followed by other scholars, whose work made the Bible widely available in the vernacular and contributed significantly to the emergence of national languages." (30)

Influenced by Luther's writings, William Tyndale began work on an English translation of the New Testament. This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. (31) In 1523 he travelled to London for a meeting with Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London. Tunstall refused to support Tyndale in this venture but did not organize his persecution. Tyndale later wrote that he now realized that "to translate the New Testament… there was no place in all England" and left for Germany in April 1524.

Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms. (32)

Tyndale's Bible was heavily influenced by the writings of Martin Luther. This is reflected in the way he altered the meaning of certain important concepts. "Congregation" was employed instead of "church", and "senior" instead of "priest", "penance", "charity", "grace" and "confession" were also silently removed. (33) Melvyn Bragg has pointed out. Tyndale "loaded our speech with more everyday phrases than any other writer before or since". This included “under the sun”, “signs of the times”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “lick the dust”, “fall flat on his face”, “the land of the living”, “pour out one’s heart”, “the apple of his eye”, “fleshpots”, “go the extra mile” and “the parting of the ways”. Bragg adds: "Tyndale deliberately set out to write a Bible which would be accessible to everyone. To make this completely clear, he used monosyllables, frequently, and in such a dynamic way that they became the drumbeat of English prose." (34)

The Peasants' War

Henry Ganss has argued: "Luther the reformer had become Luther the revolutionary; the religious agitation had become a political rebellion... Luther had one prominent trait of character, which in the consensus of those who have made him a special study, overshadowed all others. It was an overweening confidence and unbending will, buttressed by an inflexible dogmatism. He recognized no superior, tolerated no rival, brooked no contradiction." (35)

Martin Luther had been born a peasant and he was sympathetic to their plight in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. In December 1521 he warned that the peasants were close to rebellion: "Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man... is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do." (36)

Thomas Müntzer was a follower of Luther and argued that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society". (37)

In August 1524, Müntzer became one of the leaders of the uprising later known as the Peasants’ War. In one speech he told the peasants: "The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: 'God has commanded that thou shalt not steal'. Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang." (38)

Martin Luther seemed to take the side of the peasants and in May 1525 he published An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia: "To the Princes and Lords... We have no one on earth to thank for this mischievous rebellion, except you princes and lords; and especially you blind bishops and mad priests and monks... since you are the cause of this wrath of God, it will undoubtedly come upon you, if you do not mend your ways in time. ... The peasants are mustering, and this must result in the ruin, destruction, and desolation of Germany by cruel murder and bloodshed, unless God shall be moved by our repentance to prevent it... If these peasants do not do it for you, others will... It is not the peasants, dear lords, who are resisting you; it is God Himself. ... To make your sin still greater, and ensure your merciless destruction, some of you are beginning to blame this affair on the Gospel and say it is the fruit of my teaching... You did not want to know what I taught, and what the Gospel is; now there is one at the door who will soon teach you, unless you amend your ways." (39)

The following year Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Mühlhausen town council and setting up a type of communistic society. By the spring of 1525 the rebellion had spread to much of central Germany. The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto titled The Twelve Articles of the Peasants; the document is notable for its declaration that the rightness of the peasants’ demands should be judged by the Word of God, a notion derived directly from Luther’s teaching that the Bible is the sole guide in matters of morality and belief. (40)

Some of Luther's critics blamed him for the Peasants' War: "The peasant outbreaks, which in milder forms were previously easily controlled, now assumed a magnitude and acuteness that threatened the national life of Germany.... A fire of repressed rebellion and infectious unrest burned throughout the nation. This smouldering fire Luther fanned to a fierce flame by his turbulent and incendiary writings, which were read with avidity by all, and by none more voraciously than the peasant, who looked upon 'the son of a peasant' not only as an emancipator from Roman impositions, but the precursor of social advancement." (41)

Although it is true that Martin Luther he agreed with many of the peasants' demands, he hated armed strife. He travelled round the country districts, risking his life to preach against violence. Martin Luther also published the tract, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants, where he urged the princes to "brandish their swords, to free, save, help, and pity the poor people forced to join the peasants - but the wicked, stab, smite, and slay all you can." Some of the peasant leaders reacted to the tract by describing Luther as a spokesman for the oppressors. (42)

In the tract Luther made it clear that he now had no sympathy for the rebellious peasants: "The pretences which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil's work that they are at.... They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands... Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do."

Luther called on the nobility of Germany to destroy the rebels: "They (the peasants) are starting a rebellion, and violently robbing and plundering monasteries and castles which are not theirs, by which they have a second time deserved death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers ... if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man. For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster." (43)

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007), pointed out the Luther strongly defended the inequality that existed in 16th century Germany. "Luther told the peasants... the rebels have no mandate from God to challenge their masters and, as Jesus had shown by his rebuking of Peter who had drawn the sword in the Garden of Gethsemane, violence was never an option for the Christian. Vengeance and the rightings of wrongs belonged to God... Luther went through their twelve demands. The abolition of serfdom was fanciful nonsense; equality under the Gospel does not translate into the removal of social grading. Without class distinctions society would disintegrate into anarchy. By the same token, the withholding of tithes would be an unwarranted attack on the economic working of the prevailing system." (44)

Thomas Müntzer led about 8,000 peasants into battle in Frankenhausen on 15th May 1525. Müntzer told the peasants: "Forward, forward, while the iron is hot. Let your swords be ever warm with blood!" Armed with mostly scythes and flails they stood little chance against the well-armed soldiers of Philip I of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony. The combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack resulted in the peasants fleeing in panic. Over 3,000 peasants were killed whereas only four of the soldiers lost their lives. (45)

Müntzer was captured, tortured and finally executed on 27th May, 1525. His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who might again preach treasonous doctrines. Other ringleaders were also executed. "Meanwhile, all over Germany, the mopping-up operation got under way as the princes exacted their revenge and reasserted their authority. Men who had taken up arms or simply against their masters or who fell foul of informers were imprisoned or beheaded... To any unbiased commentator, then or twice, the reaction has seemed to be out of all proportion to the offence." (46)

Martin Luther wrote to his friend, Nicolaus von Amsdorf, justifying his position on the Peasants War: "My opinion is that it is better that all the peasants be killed than that the princes and magistrates perish, because the rustics took the sword without divine authority. The only possible consequence of their satanic wickedness would be the diabolic devastation of the kingdom of God. Even if the princes abuse their power, yet they have it of God, and under their rule the kingdom of God at least has a chance to exist. Wherefore no pity, no tolerance should be shown to the peasants, but the fury and wrath of God should be visited upon those men who did not heed warning nor yield when just terms were offered them, but continued with satanic fury to confound everything... To justify, pity, or favor them is to deny, blaspheme, and try to pull God from heaven." (47)

In July 1525, published An Open Letter Against the Peasants, where he attempted to regain the support of those who had supported the rebels: "All my words were against the obdurate, hardened, blinded peasants, who would neither see nor hear, as anyone may see who reads them; and yet you say that I advocate the slaughter of the poor captured peasants without mercy.... On the obstinate, hardened, blinded peasants, let no one have mercy. They say... that the lords are misusing their sword and slaying too cruelly. I answer: What has that to do with my book? Why lay others' guilt on me? If they are misusing their power, they have not learned it from me; and they will have their reward ... See, then, whether I was not right when I said, in my little book, that we ought to slay the rebels without any mercy. I did not teach, however, that mercy ought not to be shown to the captives and those who have surrendered." (48)

Martin Luther wrote to Philipp Melanchthon asking his for his support in this struggle: "I hear of nothing said or done by them that Satan could not also do or imitate... God has never sent anyone, not even the Son himself, unless he was called through men or attested by signs... I have always expected Satan to touch this sore, but he did not want to do it through the papists. It is among us and among our followers that he is stirring up this grievous schism, but Christ will quickly trample hum under our feet." (49)

Marriage of Priests

Luther also tackled the subject of priests and marriage. He argued out that nowhere in the Bible was the celibacy of priests commanded nor their marriage forbidden. He pointed out that all the apostles except John were married, and that the Bible portrays Paul as a widower. Luther went on to suggest that the prohibition of marriage increased sin, shame, and scandal without end. He quoted from Paul’s First Epistle to Timothy to justify his position: “A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt to teach; not given to wine, no striker, not greedy of filthy lucre; but patient, not a brawler, not covetous.” Luther denied that this or any other pope had any standing whatever to legislate human sexuality. “Does the pope set up laws?” he had asked in one essay. “Let him set them up for himself and keep hands off my liberty.” (50)

Katherine von Bora was one of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, when he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels. She was a woman from a noble family who had been placed in the convent as a child. For the next two years she worked as a servant in the house of the artist, Lucas Cranach. According to Derek Wilson: "Catherine was comely (perhaps even plain); she was intelligent; and she had a mind of her own. She set her face against being married off to the first man who would have her.... At length a suitor was found who did please her. This was Jerome Baumgartner, a wealthy, young burger from Nuremberg. Sadly, Baumgartner's family persuaded him that he could do better for himself and a disconsolate Catherine was left on the shelf." (51)

Martin Luther then tried to arrange for Katherine to marry Casper Glatz, a fellow theologian. She appealed to Nicolaus von Amsdorf and he wrote to his friend on her behalf: "What in the devil are you up to that you try to persuade good Kate and force that old skinflint, Glatz, on her. She doesn't go for him and has neither love nor affection for him." Catherine made it clear that she wanted to marry Luther. (52)

On a visit to his parents, Luther's father asked him: how long was Martin going to go on advising other ex-monks to marry while refusing to set an example himself. On 13th June 13, 1525, Luther married Katherine. Hans J. Hillerbrand has argued that this decision was based on a number of factors. This included the fact that he regarded the Roman Catholic Church’s insistence on clerical celibacy as the work of the Devil. (53)

Martin Luther explained his decision in a letter to Nicolaus von Amsdorf: "The rumour is true that I was suddenly married to Katherine. I did this to silence the evil mouths which are so used to complaining about me... In addition, I also did not want to reject this unique opportunity to obey my father's wish for progeny, which he so often expressed. At the same time I also wanted to confirm what I have taught by practising it; for I find so many timid in spite of such great light from the gospel. god has willed and brought about this step. For I feel neither passionate love nor burning desire for my spouse." (54)

Even his fiercest critics admit that Luther' marriage to Katherine von Bora was a happy one. It is claimed that "Katherine proved to be a plain, frugal, domestic housewife; her interest in her fowls, piggery, fish-pond, vegetable garden, home-brewery, were deeper and more absorbing than in the most gigantic undertakings of her husband". (55) Over the next few years she gave birth to six children: John (7th June, 1526), Elizabeth (10th December, 1527), Magdalene (4th May, 1529), Martin (9th November, 1531), Paul (28th January, 1533) and Margaret (17th December, 1534).

The German Bible

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has pointed out: "He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote". (56)

The translation of the Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534. Luther worked closely with Philipp Melanchthon, Johannes Bugenhagen, Caspar Creuziger and Matthäus Aurogallus on the project. There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg. This included the work of Lucas Cranach.

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "With the New Testament Luther staked a place at the very forefront of the development of German literature. His style was vigorous, colourful and direct. Anyone reading it could almost hear the author proclaiming the sacred text and that was no fortuitous accident; Luther's written language was akin to the oral delivery of his own impassioned sermons. His translation was couched in compelling prose." (57)

Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). He also commissioned Cranach to provide cartoon illustrations for his German translation of the New Testament, which became a best seller, a major event in the history of the Reformation. (58)

Augsburg Confession

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 Philipp Melanchthon was the leading representative of the Reformation, and it was he who prepared the Augsburg Confession, which influenced other credal statements in Protestantism. In the Confession he sought to be as inoffensive to the Catholics as possible while forcefully stating the Evangelical position. As Klemens Löffler has pointed out: "He was not qualified to play the part of a leader amid the turmoil of a troublous period. The life which he was fitted for was the quiet existence of the scholar. He was always of a retiring and timid disposition, temperate, prudent, and peace-loving, with a pious turn of mind and a deeply religious training. He never completely lost his attachment for the Catholic Church and for many of her ceremonies.... He invariably sought to preserve peace as long as might be possible." (59)

Martin Luther wrote a pamphlet, Exhortation to all Clergy Assembled at Augsburg that caused Melanchthon considerable distress: "You are the devil's church! She (the Catholic Church) is a liar against God's word and a murderess, for she sees that her god, the devil, is also a liar and a murderer... We want you to be forced to it by God's word and have you worn down like blasphemers, persecutors and murderers, so that you humble yourself before God, confess your sins, murder and blasphemy against God's word." (60)

Luther had the pamphlet printed and 500 copies sent to Augsburg. As Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) pointed out: "While Melanchthon and the others were making serious efforts to reach a compromise solution, their mentor, like some prophet of old, was despatching from his mountain retreat messages of fiery denunciation and exhortations to his friends to stick to their guns." (61)

Melanchthon's Apology of the Confession of Augsburg (1531) became an important document in the history of Lutherism. Melanchthon was accused of being too willing to compromise with the Catholic Church. However, he argued: "I know that the people decry our moderation; but it does not become us to heed the clamour of the multitude. We must labour for peace and for the future It will prove a great blessing for us all if unity be restored in Germany." (62)

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has written in some detail about the relationship between Luther and Melanchthon: "Melanchthon, seeing Luther's faults and regretting them, admired him with a rueful affection and reverenced him as the restorer of truth in the Church. His respect for tradition and authority suited Luther's underlying conservatism, and he supplied learning, a systematic theology, a mode of education, an ideal for the universities, and an even and tranquil spirit." (63)

Martin Luther and Anabaptists

Anabaptism emerged in Germany during the Protestant Reformation. It is claimed that the movement had been inspired by the teachings of Martin Luther and the publication of the Bible in German. Now able to read the Bible in their own language, they began to question the teachings of the Catholic Church. One of the movement's leaders, Balthasar Hubmaier, a former pupil of Luther, pointed out: “In all disputes concerning faith and religion, the scriptures alone, proceeding from the mouth of God, ought to be our level and rule.” (64)

The Anabaptists argued that Jesus taught that man should act in a non-violent way. They quoted him as saying: "Love your enemy and pray for those who persecute you.” (Luke 6.27) "Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called sons of God." (Matthew 5.9) “Do not use force against an evil man.. But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” (Matthew 5.39) “Do not resist evil with evil.” (Luke 6.37) “He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matthew 26.52)

The Anabaptists were the among the first to point out the lack of explicit biblical support for infant baptism. They repudiated their own baptism as infants. They considered the public confession of sin and faith, sealed by adult baptism, to be the only proper baptism. They agreed with Huldrych Zwingli that infants are not punishable for sin until they become aware of good and evil and can exercise their own free will, repent, and accept baptism. (65)

Anabaptists believed that "they were the true elect of God who did not require any external authority". (66) They therefore advocated separation of church and state. Anabaptists advocated complete freedom of belief and denied that the state had a right to punish or execute anyone for religious beliefs or teachings. This was a revolutionary notion in the 16th century and every government in Europe saw them as a potential threat to both religious and political power.

Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "The Anabaptists not only objected to infant baptism, but also denied the divinity of Christ or said that he was not born to the Virgin Mary. They advocated a primitive form of Communism, denouncing private property and urging that all goods should be owned by the people in common." (67) Anabaptists believed all people were equal and kept their hats on before magistrates and superior officials and their pacifism made them reject military service. (68)

Martin Luther was completely opposed to the Anabaptists and denounced people such as Balthasar Hubmaier and Pilgram Marpeck as satanic agents and enemies of the Gospel. Luther was especially upset by Hubmaier's teaching that people should not swear oaths. "Since solemn vows were a vital part of the making and sustaining of all relationships - master and apprentice, lord and servant, mercenary general and paymaster, what Hubmaier's followers proposed was nothing less than a breakdown of society." (69) Luther argued that all Anabaptists should be "hanged as seditionists". (70)

Martin Luther's Anti-Semitism

In his early career Martin Luther held tolerant views towards the Jews. In 1519 he had written: "Absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews... What Jew would consent to enter our ranks when he sees the cruelty and enmity we wreak on them - that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts?" (71) In 1523, he wrote: "I hope that if one deals in a kindly way with the Jews and instructs them carefully from Holy Scripture, many of them will become genuine Christians and turn again to the faith of their fathers, the prophets and patriarchs. They will only be frightened further away from it if their Judaism is so utterly rejected that nothing is allowed to remain, and they are treated only with arrogance and scorn. If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles. Since they dealt with us Gentiles in such brotherly fashion, we in our turn ought to treat the Jews in a brotherly manner in order that we might convert some of them." (72)

Luther was confident that his writings would convert Jews to Christianity. This had not happened and in 1542 he was upset when news reached him that proselytising Jews had succeeded in converting some Christian men, who had denied Christ and submitted to circumcision. He also recorded that three rabbis had called on him, apparently with the same objective. (73)

Soon afterwards his thirteen-year-old daughter, Magdalene, died. He confided to a friend: "My most beloved daughter Magdalene has departed from me and gone to the heavenly Father. She passed away having total faith in Christ. I have overcome the emotional shock typical of a father but only with a certain threatening murmur against death. By means of this disdain I have tamed my tears. I loved her so very much." (74)

In the weeks following his daughter's death he wrote On the Jews and Their Lies. The greater part of the work was a careful analysis of the Old Testament. However, in the final section of the book, Luther addressed himself to the question of how Christian rulers should treat their Jewish subjects. As Derek Wilson pointed out: "Attitudes to his harsh and uncompromising advice have inevitably been coloured by the appalling events of later centuries and predominately by the Holocaust... In 1523 he had been an assimilationist; now he had become an exclusionist. No longer were the Jews to be won over by kindness." (75)

Luther wrote: "What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews? Since they live among us, we dare not tolerate their conduct, now that we are aware of their lying and reviling and blaspheming. If we do, we become sharers in their lies, cursing and blasphemy... First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them... Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. For they pursue in them the same aims as in their synagogues. Instead they might be lodged under a roof or in a barn, like the gypsies. This will bring home to them that they are not masters in our country, as they boast, but that they are living in exile and in captivity, as they incessantly wail and lament about us before God. Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them... Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb." (76)

The author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has attempted to defend Luther's tract: "Luther did not advocate extermination. And he was not a racist. His objection was entirely to the Jews' religious beliefs and the behaviour that stemmed from those beliefs. He did not support inquisitorial methods to obtain conversions - use of informers, third-degree interrogation, torture and the threat of the stake... To individual Jews (of whom he met very few) he was his usual open, generous self." (77)

Hans J. Hillerbrand takes a less sympathetic approach to Martin Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies: "Such were hardly irenic words from a minister of the gospel, and none of the explanations that have been offered - his deteriorating health and chronic pain, his expectation of the imminent end of the world, his deep disappointment over the failure of true religious reform - seem satisfactory." (78) Roland H. Bainton agrees and has written that "one could wish that Luther had died before ever this tract was written". (79)

By this stage of his life his health was poor. "Prolonged attacks of dyspepsia, nervous headaches, chronic granular kidney disease, gout, sciatic rheumatism, middle ear abscesses, above all vertigo and gall stone colic were intermittent or chronic ailments that gradually made him the typical embodiment of a supersensitively nervous, prematurely old man. These physical impairments were further aggravated by his notorious disregard of all ordinary dietetic or hygienic restrictions." (80)

Martin Luther died on 18th February 1546.

Primary Sources

(1) Hans J. Hillerbrand, Martin Luther: Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

Luther’s new monastic life conformed to the commitment that countless men and women had made through the centuries - an existence devoted to an interweaving of daily work and worship. His spartan quarters consisted of an unheated cell furnished only with a table and chair. His daily activities were structured around the monastic rule and the observance of the canonical hours, which began at 2:00 in the morning. In the fall of 1506, he was fully admitted to the order and began to prepare for his ordination to the priesthood. He celebrated his first mass in May 1507 with a great deal of fear and trembling, according to his own recollection.

(2) Henry Ganss, Martin Luther: The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910)

Of Luther's monastic life we have little authentic information, and that is based on his own utterances, which his own biographers frankly admit are highly exaggerated, frequently contradictory, and commonly misleading. Thus the alleged custom by which he was forced to change his baptismal name Martin into the monastic name Augustine, a proceeding he denounces as "wicked" and "sacrilegious", certainly had no existence in the Augustinian Order.

His accidental discovery in the Erfurt monastery library of the Bible, "a book he had never seen in his life", or Luther's assertion that he had "never seen a Bible until he was twenty years of age", or his still more emphatic declaration that when Carlstadt was promoted to the doctorate "he had as yet never seen a Bible and I alone in the Erfurt monastery read the Bible", which, taken in their literal sense, are not only contrary to demonstrable facts, but have perpetuated misconception, bear the stamp of improbability written in such obtrusive characters on their face, that it is hard, on an honest assumption, to account for their longevity. The Augustinian rule lays especial stress on the monition that the novice "read the Scripture assiduously, hear it devoutly, and learn it fervently".... Protestant writers of repute have abandoned this legend altogether.

There is no reason to doubt that Luther's monastic career thus far was exemplary, tranquil, happy; his heart at rest, his mind undisturbed, his soul at peace. The metaphysical disquisitions, psychological dissertations, pietistic maunderings about his interior conflicts, his theological wrestlings, his torturing asceticism, his chafing under monastic conditions, can have little more than an academic, possibly a psychopathic value. They lack all basis of verifiable data. Unfortunately Luther himself in his self-revelation can hardly be taken as a safe guide. Moreover, with an array of evidence, thoroughness of research, fullness of knowledge, and unrivalled mastery of monasticism, scholasticism, and mysticism.

(3) Martin Luther, On the Pope as an Infallible Teacher (25 June 1520)

If we punish thieves with the yoke, highwaymen with the sword, and heretics with fire, why do we not rather assault these monsters of perdition, these cardinals, these popes, and the whole swarm of the Roman Sodom, who corrupt youth and the Church of God? Why do we not rather assault them with arms and wash our hands in their blood?

(4) Martin Luther, Reply to the Answer of the Leipzig Goat (January 1521)

All the strife and the wars of the Old Testament prefigured the preaching of the Gospel which must produce strife, dissension, disputes, disturbance. Such was the condition of Christendom when it was at its best, in the times of the apostles and martyrs. That is a blessed dissension, disturbance, and commotion which is produced by the Word of God; it is the beginning of true faith and of war against false faith; it is the coming again of the days of suffering and persecution and the right condition of Christendom.

(5) Martin Luther, An Earnest Exhortation for all Christians, Warning Them Against Insurrection and Rebellion (December 1521)

Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man . . . is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do ...

According to the Scriptures such fear and anxiety come upon the enemies of God as the beginning of their destruction. Therefore it is right, and pleases me well, that this punishment is beginning to be felt by the papists who persecute and condemn the divine truth. They shall soon suffer more keenly ... Already an unspeakable severity and anger without limit has begun to break upon them. The heaven is iron, the earth is brass. No prayers can save them now. Wrath, as Paul says of the Jews, is come upon them to the uttermost. God's purposes demand far more than an insurrection. As a whole they are beyond the reach of help ... The Scriptures have foretold for the pope and his followers an end far worse than bodily death and insurrection.

(6) Owen Chadwick, The Reformation (1964)

He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote.

(7) Derek Wilson, Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007)

With the New Testament Luther staked a place at the very forefront of the development of German literature. His style

was vigorous, colourful and direct. Anyone reading it could almost hear the author proclaiming the sacred text and that was no fortuitous accident; Luther's written language was akin to the oral delivery of his own impassioned sermons. His translation was couched in compelling prose. But what did it compel - or entreat - people to believe?This was no objective rendering of a Greek original into a sixteenth-century vernacular. Having, as he believed, fathomed the "true" gospel, Luther was intent on communicating his insights to others. Each book was provided with its own preface and marginal glosses, designed to instruct the reader in the understanding of all the key concepts - "law", "grace", "sin", "faith", "righteousness", etc. Anti-Roman polemic also had its place in the new translation.

Luther did not hesitate to point out the contemporary application of first-century teaching. For example, the papacy was clearly identified as the beast of Revelation in Luther's glosses and the vivid woodcuts provided by Lucas Cranach. Luther's New Testament was the campaign manual of the Reformation...

This phenomenon that appeared in England a few years later had its beginning in Germany in the early 1520s. Bible mania is something the modern reader may well find difficult to understand. In an age when the Bible remains the least read best-seller and is widely regarded as out-dated and irrelevant we find it hard to get inside the minds of people who risked arrest, imprisonment and death by owning, reading and selling copies of the sacred text. Luther's New Testament was, of course, banned and, of course, that only boosted sales. For young scholars and other radically minded people the fact that this fruit was forbidden only added piquancy to its taste. Like Tyndale's English version a few years later, the book attracted excited, devoted students. The lengths the authorities went to lay their hands on smuggled volumes is testimony to its success. The emperor ordered all copies to be handed in and some senior ecclesiastics even offered to pay for the books thus surrendered. Not many were.

Why did this translation, coming when it did, strike such a common chord? It was because books were, for the first time, becoming part of the everyday experience of people's lives. For some they were, doubtless, little more than status symbols - statements of their owners' wealth and sophistication. But for others they opened whole new worlds of knowledge and imagination hitherto available only to the well-educated (primarily senior clergy and the sons of aristocrats). An extensive "middle class" could now afford to buy what was coming from the presses. And the most intriguing book of all was the Bible. For as long as anyone could remember priests and friars had talked about it, theologians had argued about it, artists had represented scenes from it in paint and stained glass and now the controversy over what it actually meant had "hit the headlines". It was news. Small wonder, then, that people flocked to acquire copies, to become literate in order to read them or to resort secretly to the homes of neighbours where the forbidden words were expounded. Bible study became a swelling, unstoppable underground movement. Scripture written in language that ordinary literate people could understand emerged as the symbol and guarantor of personal freedom. Men and women no longer had to take their religion from the priest, to accept uncritically "truths" proclaimed by men for whom they had limited respect. They could read the Gospel for themselves, interpret it at will, and even write their own religious tracts, expounding and applying holy writ. As we shall see, one result of the publication of Lutheran Bibles was the releasing of a flood of books and pamphlets written by laymen (and women!). Merchants, artisans, soldiers and housewives turned into theologians and rushed into print.

But it was not just the serum of a purified biblical text that Luther set coursing through the veins of Germany. Translation implies interpretation and it was his exposition of the New Testament message that made such a dramatic impact. In the introductory notes and the marginal glosses he wrote for the New Testament books Luther identified and laid out the methodology that later ages would call "Evangelicalism". This was far and away the most important contribution of Martin Luther to the history of religion.

(8) Henry Ganss, Martin Luther: The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910)

Luther the reformer had become Luther the revolutionary; the religious agitation had become a political rebellion. Luther's theological attitude at this time, as far as a formulated cohesion can be deduced, was as follows:

* The Bible is the only source of faith; it contains the plenary inspiration of God; its reading is invested with a quasi-sacramental character.

* Human nature has been totally corrupted by original sin, and man, accordingly, is deprived of free will. Whatever he does, be it good or bad, is not his own work, but God's.

* Faith alone can work justification, and man is saved by confidently believing that God will pardon him. This faith not only includes a full pardon of sin, but also an unconditional release from its penalties.

* The hierarchy and priesthood are not Divinely instituted or necessary, and ceremonial or exterior worship is not essential or useful. Ecclesiastical vestments, pilgrimages, mortifications, monastic vows, prayers for the dead, intercession of saints, avail the soul nothing.

* All sacraments, with the exception of baptism, Holy Eucharist, and penance, are rejected, but their absence may be supplied by faith.

* The priesthood is universal; every Christian may assume it. A body of specially trained and ordained men to dispense the mysteries of God is needless and a usurpation.

* There is no visible Church or one specially established by God whereby men may work out their salvation.

(9) Victor S. Navasky, The Art of Controversy (2012)

Hans Holbein... created a woodcut depicting Martin Luther as "the German Hercules," in which Luther beats scholastics as Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas into submission with a nail-studded club.

Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). He also commissioned Cranach to provide cartoon illustrations for his German translation of the New Testament, which became a best seller, a major event in the history of the Reformation.

(10) James Reston Jr., Salon Magazine (30th May, 2015)

Nowhere in the Bible was the celibacy of priests commanded nor their marriage forbidden, he insisted. Indeed, the contrary was true. He pointed out that James (the first martyred apostle) and all the apostles except John were married, and that the Bible portrays Paul as a widower. He invoked Paul’s letters to Timothy and to Titus: a bishop must be blameless and be husband to only one wife. The first prohibition of marriage was proclaimed in the year 385 by Pope Siricus, and it was done out of “sheer wantonness.”

Worse than wantonness, it was the work of the Devil, Luther argued, for it increased sin, shame, and scandal without end. Prohibiting prelates from marital bliss was the effusion of the Anti-Christ. Again he invoked Paul’s First Letter to Timothy: “There shall come false prophets, seducing spirits, speaking lies in hypocrisy, forbidding marriage” (1 Timothy 4:1–4). Of the priest who takes a secret lover, Luther said, “his conscience is troubled, yet no one does anything to help him, though he might easily be helped.” Moreover, the controversy had led to the catastrophic schism between the Eastern and Western churches in the eleventh century. In the eastern Greek Orthodox Church the priest was required to marry a woman for the good of his community and himself. Luther seemed to like that idea, and he proposed that every Christian community appoint a pious and learned person as a minister, leaving him free to marry or not.

For biblical certification he continued to rely on Paul’s First Epistle to Timothy. According to 1 Timothy 3:2–3, the institution was specifically sanctioned: “A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt to teach; not given to wine, no striker, not greedy of filthy lucre; but patient, not a brawler, not covetous.”

Most of all, he denied that this or any other pope had any standing whatever to legislate human sexuality. “Does the pope set up laws?” he had asked in his essay on the church’s Babylonian captivity. “Let him set them up for himself and keep hands off my liberty.” If a priest was supposed to be celibate, what standing did he have to set up rules about sex for the laity?

But Luther did not stop there. He ventured unhesitatingly into areas where even a layperson much less a priest feared to tread: into questions of adultery, impotence, fornication, and masturbation. What was a wife to do when she found herself married to an impotent husband? Luther’s answer: she should seek a divorce and marry one more suitable and satisfying. But what if the impotent husband should not agree? Luther’s answer: then with the sufferance of her husband—he was not really a husband anyway, but merely the man dwelling with her under the same roof—she should have intercourse with another, perhaps the husband’s brother, and the children from such a union should be regarded as rightful heirs.

And should a spouse wish to obtain a divorce, what about the Catholic law against remarriage? Luther answered that he or she should be permitted to remarry: “Yet it is still a greater wonder to me why they compel a man to remain unmarried after being separated from his wife by divorce, and why they will not permit him to remarry. For if Christ permits divorce on the ground of fornication (Matthew 5:32) and compels no one to remain unmarried . . . then he certainly seems to permit a man to marry another woman in the place of the one who has been put away.” But what about the Catholic Church’s prohibition of divorce, all divorce? “The tyranny of the laws permits no divorce,” Luther wrote. “But the woman is free through the divine law and cannot be compelled to suppress her carnal desires. Therefore the man ought to concede her right and give up to somebody else the wife who is his only in outward appearance.” Still he detested divorce, he insisted, and preferred bigamy, considering it the lesser of evils and validated by multiple stories in the Old Testament. And annulment? Well, that process was far too complicated and time-consuming, not to mention the toll it took on all the parties.

(11) Hans J. Hillerbrand, Martin Luther: Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

On June 13, 1525, Luther married Katherine of Bora, a former nun. Katherine had fled her convent together with eight other nuns and was staying in the house of the Wittenberg town secretary. While the other nuns soon returned to their families or married, Katherine remained without support. Luther was likewise at the time the only remaining resident in what had been the Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg; the other monks had either thrown off the habit or moved to a staunchly Catholic area. Luther’s decision to marry Katherine was the result of a number of factors. Understandably, he felt responsible for her plight, since it was his preaching that had prompted her to flee the convent. Moreover, he had repeatedly written, most significantly in 1523, that marriage is an honourable order of creation, and he regarded the Roman Catholic Church’s insistence on clerical celibacy as the work of the Devil. Finally, he believed that the unrest in Germany, epitomized in the bloody Peasants’ War, was a manifestation of God’s wrath and a sign that the end of the world was at hand. He thus conceived his marriage as a vindication, in these last days, of God’s true order for humankind.

(12) Martin Luther, letter to Nicolaus von Amsdorf (27th June, 1525)

The rumour is true that I was suddenly married to Katherine. I did this to silence the evil mouths which are so used to complaining about me... In addition, I also did not want to reject this unique opportunity to obey my father's wish for progeny, which he so often expressed. At the same time I also wanted to confirm what I have taught by practising it; for I find so many timid in spite of such great light from the gospel. god has willed and brought about this step. For I feel neither passionate love nor burning desire for my spouse.

(13) Martin Luther, An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia (May 1525)

To the Princes and Lords... We have no one on earth to thank for this mischievous rebellion, except you princes and lords; and especially you blind bishops and mad priests and monks... since you are the cause of this wrath of God, it will undoubtedly come upon you, if you do not mend your ways in time. ... The peasants are mustering, and this must result in the ruin, destruction, and desolation of Germany by cruel murder and bloodshed, unless God shall be moved by our repentance to prevent it.

For you ought to know, dear lords, that God is doing this because this raging of yours cannot and will not and ought not be endured for long. You must become different men and yield to God's Word. If you do not do this amicably and willingly, then you will be compelled to it by force and destruction. If these peasants do not do it for you, others will... It is not the peasants, dear lords, who are resisting you; it is God Himself. ... To make your sin still greater, and ensure your merciless destruction, some of you are beginning to blame this affair on the Gospel and say it is the fruit of my teaching... You did not want to know what I taught, and what the Gospel is; now there is one at the door who will soon teach you, unless you amend your ways.

(14) Martin Luther, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants (1525)

The pretences which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil's work that they are at.... They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands... Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do...

They are starting a rebellion, and violently robbing and plundering monasteries and castles which are not theirs, by which they have a second time deserved death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers ... if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man.

For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster. Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you, and a whole land with you.

They cloak this terrible and horrible sin with the Gospel, call themselves "Christian brethren." ... Thus they become the greatest of all blasphemers of God and slanderers of His holy Name, serving the devil, under the outward appearance of the Gospel, thus earning death in body and soul ten times over. ... Fine Christians these! I think there is not a devil left in hell; they have gone into the peasants. Their raving has gone beyond all measure.

I will not oppose a ruler who, even though he does not tolerate the Gospel, will smite and punish these peasants without offering to submit the case to judgment... If anyone thinks this too hard, let him remember that rebellion is intolerable and that the destruction of the world is to be expected every hour.

(15) Martin Luther, letter of Nicolaus von Amsdorf (25 May 1525)

My opinion is that it is better that all the peasants be killed than that the princes and magistrates perish, because the rustics took the sword without divine authority. The only possible consequence of their satanic wickedness would be the diabolic devastation of the kingdom of God. Even if the princes abuse their power, yet they have it of God, and under their rule the kingdom of God at least has a chance to exist. Wherefore no pity, no tolerance should be shown to the peasants, but the fury and wrath of God should be visited upon those men who did not heed warning nor yield when just terms were offered them, but continued with satanic fury to confound everything... To justify, pity, or favor them is to deny, blaspheme, and try to pull God from heaven.

(16) Martin Luther, An Open Letter Against the Peasants (July 1525)

All my words were against the obdurate, hardened, blinded peasants, who would neither see nor hear, as anyone may see who reads them; and yet you say that I advocate the slaughter of the poor captured peasants without mercy.... On the obstinate, hardened, blinded peasants, let no one have mercy.

They say... that the lords are misusing their sword and slaying too cruelly. I answer: What has that to do with my book? Why lay others' guilt on me? If they are misusing their power, they have not learned it from me; and they will have their reward ...

See, then, whether I was not right when I said, in my little book, that we ought to slay the rebels without any mercy. I did not teach, however, that mercy ought not to be shown to the captives and those who have surrendered.

(17) Martin Luther, That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew (1523)

I hope that if one deals in a kindly way with the Jews and instructs them carefully from Holy Scripture, many of them will become genuine Christians and turn again to the faith of their fathers, the prophets and patriarchs. They will only be frightened further away from it if their Judaism is so utterly rejected that nothing is allowed to remain, and they are treated only with arrogance and scorn. If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles. Since they dealt with us Gentiles in such brotherly fashion, we in our turn ought to treat the Jews in a brotherly manner in order that we might convert some of them. For even we ourselves are not yet all very far along, not to speak of having arrived.

When we are inclined to boast of our position we should remember that we are but Gentiles, while the Jews are of the lineage of Christ. We are aliens and in-laws; they are blood relatives, cousins, and brothers of our Lord. Therefore, if one is to boast of flesh and blood, the Jews are actually nearer to Christ than we are, as St. Paul says in Romans 9. God has also demonstrated this by his acts, for to no nation among the Gentiles has he granted so high an honor as he has to the Jews. For from among the Gentiles there have been raised up no patriarchs, no apostles, no prophets, indeed, very few genuine Christians either. And although the gospel has been proclaimed to all the world, yet He committed the Holy Scriptures, that is, the law and the prophets, to no nation except the Jews, as Paul says in Romans 3 and Psalm 147, "He declares his word to Jacob, his statutes and ordinances to Israel. He has not dealt thus with any other nation; nor revealed his ordinances to them."

(18) Martin Luther, On the Jews and Their Lies (1543)

I had made up my mind to write no more either about the Jews or against them. But since I learned that these miserable and accursed people do not cease to lure to themselves even us, that is, the Christians, I have published this little book, so that I might be found among those who opposed such poisonous activities of the Jews who warned the Christians to be on their guard against them. I would not have believed that a Christian could be duped by the Jews into taking their exile and wretchedness upon himself. However, the devil is the god of the world, and wherever God's word is absent he has an easy task, not only with the weak but also with the strong...

Learn from this, dear Christian, what you are doing if you permit the blind Jews to mislead you. Then the saying will truly apply, "When a blind man leads a blind man, both will fall into the pit" (Luke 6:39). You cannot learn anything from them except how to misunderstand the divine commandments...

Therefore be on your guard against the Jews, knowing that wherever they have their synagogues, nothing is found but a den of devils in which sheer selfglory, conceit, lies, blasphemy, and defaming of God and men are practiced most maliciously and veheming his eyes on them.

Moreover, they are nothing but thieves and robbers who daily eat no morsel and wear no thread of clothing which they have not stolen and pilfered from us by means of their accursed usury. Thus they live from day to day, together with wife and child, by theft and robbery, as archthieves and robbers, in the most impenitent security.

However, they have not acquired a perfect mastery of the art of lying; they lie so clumsily and ineptly that anyone who is just a little observant can easily detect it. But for us Christians they stand as a terrifying example of God's wrath.

If I had to refute all the other articles of the Jewish faith, I should be obliged to write against them as much and for as long a time as they have used for inventing their lies - that is, longer than two thousand years....

Christ and his word can hardly be recognized because of the great vermin of human ordinances. However, let this suffice for the time being on their lies against doctrine or faith...

I brief, dear princes and lords, those of you who have Jews under your rule - if my counsel does not please your, find better advice, so that you and we all can be rid of the unbearable, devilish burden of the Jews, lest we become guilty sharers before God in the lies, blasphemy, the defamation, and the curses which the mad Jews indulge in so freely and wantonly against the person of our Lord Jesus Christ, this dear mother, all Christians, all authority, and ourselves. Do not grant them protection, safeconduct, or communion with us... With this faithful counsel and warning I wish to cleanse and exonerate my conscience.

Let the government deal with them in this respect, as I have suggested. But whether the government acts or not, let everyone at least be guided by his own conscience and form for himself a definition or image of a Jew. However, we must avoid confirming them in their wanton lying, slandering, cursing, and defaming...

What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews? Since they live among us, we dare not tolerate their conduct, now that we are aware of their lying and reviling and blaspheming. If we do, we become sharers in their lies, cursing and blasphemy. Thus we cannot extinguish the unquenchable fire of divine wrath, of which the prophets speak, nor can we convert the Jews. With prayer and the fear of God we must practice a sharp mercy to see whether we might save at least a few from the glowing flames. We dare not avenge ourselves. Vengeance a thousand times worse than we could wish them already has them by the throat. I shall give you my sincere advice:

First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them. This is to be done in honor of our Lord and of Christendom, so that God might see that we are Christians, and do not condone or knowingly tolerate such public lying, cursing, and blaspheming of his Son and of his Christians. For whatever we tolerated in the past unknowingly and I myself was unaware of it will be pardoned by God. But if we, now that we are informed, were to protect and shield such a house for the Jews, existing right before our very nose, in which they lie about, blaspheme, curse, vilify, and defame Christ and us (as was heard above), it would be the same as if we were doing all this and even worse ourselves, as we very well know.

Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. For they pursue in them the same aims as in their synagogues. Instead they might be lodged under a roof or in a barn, like the gypsies. This will bring home to them that they are not masters in our country, as they boast, but that they are living in exile and in captivity, as they incessantly wail and lament about us before God.

Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them.

Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb. For they have justly forfeited the right to such an office by holding the poor Jews captive with the saying of Moses in which he commands them to obey their teachers on penalty of death, although Moses clearly adds: "what they teach you in accord with the law of the Lord." Those villains ignore that. They wantonly employ the poor people's obedience contrary to the law of the Lord and infuse them with this poison, cursing, and blasphemy.

(19) Hans J. Hillerbrand, Martin Luther: Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

Luther’s role in the Reformation after 1525 was that of theologian, adviser, and facilitator but not that of a man of action. Biographies of Luther accordingly have a tendency to end their story with his marriage in 1525. Such accounts gallantly omit the last 20 years of his life, during which much happened. The problem is not just that the cause of the new Protestant churches that Luther had helped to establish was essentially pursued without his direct involvement, but also that the Luther of these later years appears less attractive, less winsome, less appealing than the earlier Luther who defiantly faced emperor and empire at Worms. Repeatedly drawn into fierce controversies during the last decade of his life, Luther emerges as a different figure - irascible, dogmatic, and insecure. His tone became strident and shrill, whether in comments about the Anabaptists, the pope, or the Jews. In each instance his pronouncements were virulent: the Anabaptists should be hanged as seditionists, the pope was the Antichrist, the Jews should be expelled and their synagogues burned. Such were hardly irenic words from a minister of the gospel, and none of the explanations that have been offered - his deteriorating health and chronic pain, his expectation of the imminent end of the world, his deep disappointment over the failure of true religious reform - seem satisfactory.