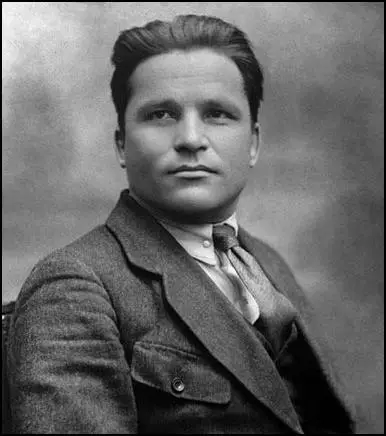

Sergei Kirov

Sergei Kirov was born in Urzhum, Russia, on 15th March, 1886. His parents died when he was young and he was brought up by his grandmother until he was seven when he was sent to an orphanage.

In 1901 he attended the Kazan Technical School. During this period he became a Marxist and joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1904. He took part in the 1905 Revolution in St. Petersburg. He was arrested but was released after three months in prison. Kirov now joined the Bolshevik faction of the SDP. He lived in Tomsk where he was involved in the printing of revolutionary literature. He also helped to organize a successful strike of railway workers.

In 1906 Kirov moved to Moscow but he was soon arrested for printing illegal literature. Several of his comrades were executed but he was sentenced to three years in prison. Kirov later wrote: "The prison library was quite satisfactory, and in addition one was able to receive all the legal writings of the time. The only hindrances to study were the savage sentences of courts as a result of which tens of people were hanged. On many a night the solitary block of the Tomsk country prison echoed with condemned men shouting heart-rending farewells to life and their comrades as they were led away to execution. But in general, it was immeasurably easier to study in prison than as an underground militant at liberty."

The Russian Revolution

The prison had a good library and during his stay he took the opportunity to improve his education. Kirov returned to revolutionary activity after his release and in 1915 he was once again arrested for printing illegal literature. After a year in custody he moved to the Caucasus. After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Kirov joined the other Bolsheviks in now attempting to undermine the government.

After the Russian Revolution he became commander of the Bolshevik military administration in Astrakhan. He also fought in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War until the defeat of General Anton Denikin in 1920. The following year Kirov was put in charge of the Azerbaijan party organization.

Sergei Kirov and the Politburo

Kirov loyally supported Joseph Stalin and in 1926 he was rewarded by being appointed head of the Leningrad party organization. He joined the Politburo in 1930 and now one of the leading figures in the party, and many felt that he was being groomed for the future leadership of the party by Stalin. However, this was not the case as Stalin saw him as a rival. As Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "In sharp contrast to Stalin, Kirov was a much younger man and an eloquent speaker, who was able to sway his listeners; above all, he possessed a charismatic personality. Unlike Stalin who was a Georgian, Kirov was also an ethnic Russian, which stood in his favour."

Kirov loyally supported Joseph Stalin and in 1926 he was rewarded by being appointed head of the Leningrad party organization. He joined the Politburo in 1930 and now one of the leading figures in the party, and many felt that he was being groomed for the future leadership of the party by Stalin. However, this was not the case as Stalin saw him as a rival. As Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "In sharp contrast to Stalin, Kirov was a much younger man and an eloquent speaker, who was able to sway his listeners; above all, he possessed a charismatic personality. Unlike Stalin who was a Georgian, Kirov was also an ethnic Russian, which stood in his favour."

Martemyan Ryutin

In the summer of 1932 Martemyan Ryutin wrote a 200 page analysis of Stalin's policies and dictatorial tactics, Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship. Ryutin argues: "The party and the dictatorship of the proletariat have been led into an unknown blind alley by Stalin and his retinue and are now living through a mortally dangerous crisis. With the help of deception and slander, with the help of unbelievable pressures and terror, Stalin in the last five years has sifted out and removed from the leadership all the best, genuinely Bolshevik party cadres, has established in the VKP(b) and in the whole country his personal dictatorship, has broken with Leninism, has embarked on a path of the most ungovernable adventurism and wild personal arbitrariness."

Ryutin also wrote up a short synopsis of the work and called it a manifesto and circulated it to friends. General Yan Berzin obtained a copy and called a meeting of his most trusted staff to discuss and denounce the work. Walter Krivitsky remembers Berzen reading excerpts of the manifesto in which Ryutin called "the great agent provocateur, the destroyer of the Party" and "the gravedigger of the revolution and of Russia."

Stalin interpreted Ryutin's manifesto as a call for his assassination. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Stalin also attacked those who were calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Stalin's close friend, also agreed with Kirov. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

On 22nd September, 1932, Martemyan Ryutin was arrested and held for investigation. During the investigation Ryutin admitted that he had been opposed to Stalin's policies since 1928. On 27th September, Ryutin and his supporters were expelled from the Communist Party. Ryutin was also found guilty of being an "enemy of the people" and was sentenced to a 10 years in prison. Soon afterwards Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were expelled from the party for failing to report the existence of Ryutin's report. Ryutin and his two sons, Vassily and Vissarion were later both executed.

Sergei Kirov and Joseph Stalin

At the 17th Party Congress in 1934, when Sergei Kirov stepped up to the podium he was greeted by spontaneous applause that equalled that which was required to be given to Joseph Stalin. In his speech he put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. The members of the Congress gave Kirov a vote of confidence by electing him to the influential Central Committee Secretariat.

Stalin now found himself in a minority in the Politburo. After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public. He feared that this would undermine his authority in the party.

The Assassination of Sergei Kirov

As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé. According to Alexander Orlov, who had been told this by Genrikh Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die.

Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin.

Zaporozhets provided him with a pistol and gave him instructions to kill Kirov in the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. However, soon after entering the building he was arrested. Zaporozhets had to use his influence to get him released. On 1st December, 1934, Nikolayev, got past the guards and was able to shoot Kirov dead. Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Genrikh Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

According to Alexander Orlov: "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov". Victor Kravchenko has pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Walter Duranty, the New York Times correspondent based in Moscow, was willing to accept this story. "The details of Kirov's assassination at first pointed to a personal motive, which may indeed have existed, but investigation showed that, as commonly happens in such cases, the assassin Nikolaiev had been made the instrument of forces whose aims were treasonable and political. A widespread plot against the Kremlin was discovered, whose ramifications included not merely former oppositionists but agents of the Nazi Gestapo. As the investigation continued, the Kremlin's conviction deepened that Trotsky and his friends abroad had built up an anti-Stalinist organisation in close collaboration with their associates in Russia, who formed a nucleus or centre around which gradually rallied divers elements of discontent and disloyalty. The actual conspirators were comparatively few in number, but as the plot thickened they did not hesitate to seek the aid of foreign enemies in order to compensate for the lack of popular support at home."

Robin Page Arnot, a member of the British Communist Party, also did his best to promote the theory that the conspiracy to kill Kirov had been led by Leon Trotsky: "In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bukharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists."

Primary Sources

(1) The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution was published by the Soviet government in 1924. The encyclopaedia included a collection of autobiographies and biographies of over two hundred people involved in the Russian Revolution. This included one written by Sergei Kirov.

The prison library was quite satisfactory, and in addition one was able to receive all the legal writings of the time. The only hindrances to study were the savage sentences of courts as a result of which tens of people were hanged. On many a night the solitary block of the Tomsk country prison echoed with condemned men shouting heart-rending farewells to life and their comrades as they were led away to execution. But in general, it was immeasurably easier to study in prison than as an underground militant at liberty.

(7) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003)

Stalin devised a plan to deal with Kirov's dangerous eminence, proposing his recall from Leningrad to become one of the four Secretaries, thereby cleverly satisfying those who wanted him promoted to the Secretariat: on paper, a big promotion; in reality, this would bring him under Stalin's observation, cutting him off from his Leningrad clientele. In Stalin's entourage, a promotion to the centre was a mixed blessing. Kirov was neither the first nor the last to protest vigorously - but, in Stalin's eyes, a refusal meant placing personal power above Party loyalty, a mortal sin. Kirov's request to stay in Leningrad for another two years was supported by Sergo and Kuibyshev. Stalin petulantly stalked out in a huff.

Sergo and Kuibyshev advised Kirov to compromise with Stalin: Kirov became the third Secretary but remained temporarily in Leningrad. Since he would have little time for Moscow, Stalin reached out to another newly elected CC member who would become the closest to Stalin of all the leaders: Andrei Zhdanov, boss of Gorky (Nizhny Novgorod), moved to Moscow as the fourth Secretary.

Kirov staggered back to Leningrad, suffering from flu, congestion in his right lung and palpitations. In March, Sergo wrote to him: "Listen my friend, you must rest. Really and truly, nothing is going to happen there without you there for 10-15 days... Our fellow countryman (their codename for Stalin) considers you a healthy man... none the less, you must take a short rest!" Kirov sensed that Stalin would not forgive him for the plot. Yet Stalin was even more suffocatingly friendly, insisting that they constantly meet in Moscow. It was Sergo, not Stalin, with whom Kirov really needed to discuss his apprehensions. `I want awfully to have a chat with you on very many questions but you can't say everything in a letter so it is better to wait until our meeting.' They certainly discussed politics in private, careful to reveal nothing on paper.

There were hints of Kirov's scepticism about Stalin's cult: on 15 July 1933, Kirov wrote formally to "Comrade Stalin" (not the usual Koba) that portraits of Stalin's photograph had been printed in Leningrad on rather "thin paper". Unfortunately they could not do any better. One can imagine Kirov and Sergo mocking Stalin's vanity. In private, Kirov imitated Stalin's accent to his Leningraders.

When Kirov visited Stalin in Moscow, they were boon companions but Artyom remembers a competitive edge to their jokes. Once at a family dinner, they made mock toasts:

"A toast to Stalin, the great leader of all peoples and all times. I'm a busy man but I've probably forgotten some of the other great things you've done too!" Kirov, who often "monopolized conversations so as to be the centre of attention", toasted Stalin, mocking the cult. Kirov could speak to Stalin in a way unthinkable to Beria or Khrushchev.

"A toast to our beloved leader of the Leningrad Party and possibly the Baku proletariat too, yet he promises me he can't read all the papers - and what else are you beloved leader of?" replied Stalin. Even the tipsy banter between Stalin and Kirov was pregnant with ill-concealed anger and resentment, yet no one in the family circle noticed that they were anything but the most loving of friends. However the `vegetarian years', as the poetess Akhmatova called them, were about to end: "the meat-eating years" were coming.

On 30 June, Adolf Hitler, newly elected Chancellor of Germany, slaughtered his enemies within his Nazi Party, in the Night of the Long Knives - an exploit that fascinated Stalin.

"Did you hear what happened in Germany?" he asked Mikoyan. "Some fellow that Hitler! Splendid! That's a deed of some skill!" Mikoyan was surprised that Stalin admired the German Fascist but the Bolsheviks were hardly strangers to slaughter themselves.

(2) Alexander Orlov was a NKVD officer who escaped to the United States.

Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov, "the beloved son of the party", a member of the Politburo, he then would be justified in demanding blood for blood.

(3) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

The details of Kirov's assassination at first pointed to a personal motive, which may indeed have existed, but investigation showed that, as commonly happens in such cases, the assassin Nikolaiev had been made the instrument of forces whose aims were treasonable and political. A widespread plot against the Kremlin was discovered, whose ramifications included not merely former oppositionists but agents of the Nazi Gestapo. As the investigation continued, the Kremlin's conviction deepened that Trotsky and his friends abroad had built up an anti-Stalinist organisation in close collaboration with their associates in Russia, who formed a nucleus or centre around which gradually rallied divers elements of discontent and disloyalty. The actual conspirators were comparatively few in number, but as the plot thickened they did not hesitate to seek the aid of foreign enemies in order to compensate for the lack of popular support at home. In other words, the whole set of trials and investigations from that of Kirov's assassin and his accomplices up to that of the generals in June 1937, have not been separate incidents but part of a continuous process which has revealed step by step the development of a conspiracy in which Trotsky and the foreign enemies of Russia had not only the strongest of incentives but ample opportunity to co-operate with the conspirators.

If one accepts these premises, it is obvious that both Trotsky and the foreign enemies would use every means in their power to deny and discredit the evidence produced at the trials. In this they have been aided by Western unfamiliarity with Soviet mentality and methods, and to no small degree, by Soviet unfamiliarity with Western mentality and methods. Thus, at the very outset, the Western world was shocked by the harshness of the reprisals which followed Kirov's murder, and already the cry was raised abroad that this wave of killings and arrests was a sign of panic on the part of the Kremlin or that Stalin and his associates were taking advantage of an "accident" to rid themselves of political opponents.

The later "treason trials" of the Kamenev-Zinoviev and Piatakov-Radek groups were used by Stalin's enemies to confirm these two assertions and to deepen the scepticism with which the extraordinary (to Western minds) nature of the confessions had been received abroad. In the fog of denials and declarations that the confessions were elicited by drugs, torture, pressure upon relatives, hypnotism or other nefarious devices of the G.P.U., foreign opinion lost sight of three important facts: first, that these same men had, individually and collectively, confessed their sins and beaten their breasts in contrition no less fully and abashedly on previous occasions; second, that the outline of the conspiracy was gradually taking shape; third, that through the maze of charge and counter-charge the thread of collusion with foreign enemies ran ever stronger and more clear. The second trial established the fact of personal contact between several of the accused and foreign - i.e., German and Japanese - representatives. This in itself meant little because Piatakov received dozens of foreigners every week in his official position, the accused railway managers of the Far Eastern lines had similar official contact with Japanese consuls and business men, and Radek was a familiar figure at most of the diplomatic receptions in Moscow. Nevertheless the element of opportunity was thus introduced to buttress the prosecution's charge of treasonable and hostile motives that led to collusion.

(4) The New Republic (9th January, 1935)

Up to last Sunday 117 persons had been executed in Soviet Russia as the direct result of the Kirov assassination. To what extent are Zinoviev and Kamenev implicated in the plot. The hysteria of Karl Radek's and Nikolai Bukharin's charges against them in Pravda and Izvestia fails to carry conviction.

Russia's right to crush Nazi-White Guard conspiracies or other plots of murder and arson no one questions; few have anything but approval for it. What is in question is the guilt of particular persons who have not been tried in an open court of law.

(5) Robin Page Arnot, The Labour Monthly (November 1937)

In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bucharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists. The group of fourteen constituting the Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Centre were brought to trial in Moscow in August 1936, found guilty, and executed. In Siberia a trial, held in November, revealed that the Kemerovo mine had been deliberately wrecked and a number of miners killed by a subordinate group of wreckers and terrorists. A second Moscow trial, held in January 1937, revealed the wider ramifications of the conspiracy. This was the trial of the Parallel Centre, headed by Pyatakov, Radek, Sokolnikov, Serebriakov. The volume of evidence brought forward at this trial was sufficient to convince the most sceptical that these men, in conjunction with Trotsky and with the Fascist Powers, had carried through a series of abominable crimes involving loss of life and wreckage on a very considerable scale. With the exceptions of Radek, Sokolnikov, and two others, to whom lighter sentences were given, these spies and traitors suffered the death penalty. The same fate was meted out to Tukhachevsky, and seven other general officers who were tried in June on a charge of treason. In the case of Trotsky the trials showed that opposition to the line of Lenin for fifteen years outside the Bolshevik Party, plus opposition to the line of Lenin inside the Bolshevik Party for ten years, had in the last decade reached its finality in the camp of counter-revolution, as ally and tool of Fascism.

(6) Victor Kravchenko, I Choose Freedom (1947)

Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks. Almost hourly the circle of those supposedly implicated, directly or "morally", was widened until it embraced anyone and everyone who had ever raised a doubt about any Stalinist policy.

(7) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003)

Poskrebyshev answered Stalin's telephone in his office. Kirov's deputy, Chudov, broke the terrible news from Leningrad. Poskrebyshev tried Stalin's phone line but he could not get an answer, sending a secretary to find him. The hozhd, according to his journal, was meeting with Molotov, Kaganovich, Voroshilov and Zhdanov, but hurriedly called Leningrad, insisting on interrogating the Georgian doctor in his native language. Then he rang back to ask what the assassin was wearing. A cap? Were there foreign items on him? Yagoda, who had already called to demand whether any foreign objects had been found on the assassin, arrived at Stalin's office at 5.50 p.m.

Mikoyan, Sergo and Bukharin arrived quickly. Mikoyan specifically remembered that 'Stalin announced that Kirov had been assassinated and on the spot, without any investigation, he said the supporters of Zinoviev (the former leader of Leningrad and the Left opposition to Stalin) had started a terror against the Party. Sergo and Mikoyan, who were so close to Kirov, were particularly appalled since Sergo had missed seeing his friend for the last time. Kaganovich noticed that Stalin 'was shocked at first'.

Stalin, now showing no emotion, ordered Yenukidze as Secretary of the Central Executive Committee to sign an emergency law that decreed the trial of accused terrorists within ten days and immediate execution without appeal after judgement. Stalin must have drafted it himself. This 1st December Law - or rather the two directives of that night - was the equivalent of Hitler's Enabling Act because it laid the foundation for a random terror without even the pretence of a rule of law. Within three years, two million people had been sentenced to death or labour camps in its name. Mikoyan said there was no discussion and no objections. As easily as slipping the safety catch on their Mausers, the Politburo clicked into the military emergency mentality of the Civil War.

If there was any opposition, it came from Yenukidze, that unusually benign figure among these amoral toughs, but it was he who ultimately signed it. The newspapers declared the laws were passed by a meeting of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee - which probably meant Stalin bullying Yenukidze in a smoky room after the meeting. It is also a mystery why the craven Kalinin, the President who was present, did not sign it. His signature had appeared by the time it was announced in the newspapers. Anyway the Politburo did not officially vote until a few days later.

Stalin immediately decided that he would personally lead a delegation to Leningrad to investigate the murder. Sergo wanted to go but Stalin ordered him to remain behind because of his weak heart. Sergo had indeed collapsed with grief and may have suffered another heart attack. His daughter remembered that "this was the only time he wept openly". His wife, Zina, travelled to Leningrad to comfort Kirov's widow.Kaganovich also wanted to go but Stalin told him that someone had to run the country. He took Molotov, Voroshilov and Zhdanov with him along with Yagoda and Andrei Vyshinsky, the Deputy Procurator, who had crossed Sergo earlier that year. Naturally they were accompanied by a trainload of secret policemen and Stalin's own myrmidons, Pauker and Vlasik. In retrospect, the most significant man Stalin chose to accompany him was Nikolai Yezhov, head of the CC's Personnel Department. Yezhov was one of those special young men, like Zhdanov, on whom Stalin was coming to depend.

The local leaders gathered, shell-shocked, at the station. Stalin played his role, that of a Lancelot heartbroken and angry at the death of a beloved knight, with self-conscious and preplanned Thespianism. When he dismounted from the train, Stalin strode up to Medved, the Leningrad NKVD chief, and slapped his face with his gloved hand.

Stalin immediately headed across town to the hospital to inspect the body, then set up a headquarters in Kirov's office where he began his own strange investigation, ignoring any evidence that did not point to a terrorist plot by Zinoviev and the Left opposition. Poor Medved, the cheerful Chekist slapped by Stalin, was interrogated first and criticized for not preventing the murder. Then the "small and shabby" murderer himself, Nikolaev, was dragged in. Nikolaev was one of those tragic, simple victims of history, like the Dutchman who lit the Reichstag fire with which this case shares many resemblances. This frail dwarf of thirty had been expelled from, and reinstated in, the Party but had written to Kirov and Stalin complaining of his plight. He was apparently in a daze and did not even recognize Stalin until they showed him a photograph. Falling to his knees before the jackbooted leader, he sobbed,"What have I done, what have I done?" Khrushchev, who was not in the room, claimed that Nikolaev kneeled and said he had done it on assignment from the Party. A source close to Voroshilov has Nikolaev stammering, "But you yourself told me... " Some accounts claim that he was punched and kicked by the Chekists present.

"Take him away!" ordered Stalin.

The well-informed NKVD defector, Orlov, wrote that Nikolaev pointed at Zaporozhets, Leningrad's deputy NKVD boss, and said, "Why are you asking me? Ask him."

Zaporozhets had been imposed on Kirov and Leningrad in 1932, Stalin and Yagoda's man in Kirov's fiefdom. The reason to ask Zaporozhets was that Nikolaev had already been detained in October loitering with suspicious intent outside Kirov's house, carrying a revolver, but had been freed without even being searched. Another time, the bodyguards had prevented him taking a shot. But four years later, when Yagoda was tried, he confessed, in testimony filled with both lies and truths, to having ordered Zaporozhets not to place any obstacles in the way of the terrorist act against Kirov.

Then the assassin's wife, Milda Draul, was brought in. The NKVD spread the story that Nikolaev's shot was a crime passionnel following her affair with Kirov. Draul was a plain-looking woman. Kirov liked elfin ballerinas but his wife was not pretty either: it is impossible to divine the impenetrable mystery of sexual taste but those who knew both believed they were an unlikely couple. Draul claimed she knew nothing. Stalin strode out into the ante-room and ordered that Nikolaev be brought round with medical attention.

"To me it's already clear that a well-organized counter-revolutionary terrorist organization is active in Leningrad... A painstaking investigation must be made." There was no real attempt to analyse the murder forensically. Stalin certainly did not wish to find out whether the NKVD had encouraged Nikolaev to kill Kirov.

Later, it is said that Stalin visited the "prick" in his cell and spent an hour with him alone, offering him his life in return for testifying against Zinoviev at a trial. Afterwards Nikolaev wondered if he would be double-crossed.

The murkiness now thickens into a deliberately blind fog. There was a delay. Kirov's bodyguard, Borisov, was brought over to be interrogated by Stalin. He alone could reveal whether he was delayed at the Smolny entrance and what he knew of the NKVD's machinations. Borisov rode in the back of an NKVD Black Crow. As the driver headed towards the Smolny, the front-seat passenger reached over and seized the wheel so that the Black Crow swerved and grazed its side against a building. Somehow in this dubious car crash, Borisov was killed. The `shaken' Pauker arrived in the anteroom to announce the crash. Such ham-handed "car crashes" were soon to become an occupational hazard for eminent Bolsheviks. Certainly anyone who wanted to cover up a plot might have wished Borisov dead. When Stalin was informed of this reekingly suspicious death, he denounced the local Cheka: "They couldn't even do that properly."

The mystery will never now be conclusively solved. Did Stalin order Kirov's assassination? There is no evidence that he did, yet the whiff of his complicity still hangs in the air. Khrushchev, who arrived in Leningrad on a separate train as a Moscow delegate, claimed years later that Stalin ordered the murder. Mikoyan, a more trustworthy witness in many ways than Khrushchev and with less to prove, came to believe that Stalin was somehow involved in the death.

Stalin certainly no longer trusted Kirov whose murder served as a pretext to destroy the Old Bolshevik cliques. His drafting of the lst December Law minutes after the death seems to stink as much as his decision to blame the murder on Zinoviev. Stalin had indeed tried to replace Kirov's friend Medved and he knew the suspicious Zaporozhets who, shortly before the murder, had gone on leave without Moscow's permission, perhaps to absent himself from the scene. Nikolaev was a pathetic bundle of suspicious circumstances. Then there were the strange events of the day of the murder: why was Borisov delayed at the door and why were there already Moscow NKVD officers in the Smolny so soon after the assassination? Borisov's death is highly suspect. And Stalin, often so cautious, was also capable of such a reckless gamble, particularly after admiring Hitler's reaction to the Reichstag fire and his purge.

(7) Nikita Khrushchev, speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party (1956)

There are reasons for the suspicion that the killer of Kirov, Nikolayev, was assisted by someone from among the people whose duty it was to protect the person of Kirov. A month and a half before the killing, Nikolayev was arrested on the grounds of suspicious behaviour but he was released and not even searched. It is an unusually suspicious circumstances that the member of the Secret Police assigned to protect Kirov was being brought for an interrogation, on 2nd December, 1934, he was killed in a car accident in which no other occupants of the car were harmed.