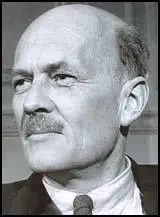

Tom Wintringham

Tom Wintringham was born in Grimsby on 15th May 1898. He later recalled: "Eight or nine generations back before my birth one of my ancestors, a Nonconformist hedge preacher, had his tongue torn out for carrying on subversive propaganda. Something of that man's attitude to life had come through to me from my parents, the most really liberal people I know."

Wintringham was educated at Arnold House Preparatory School in St. John's Wood. When he was thirteen he was sent to a Gresham School in Norfolk. He developed a strong interest in history. According to his autobiography, he became a socialist after reading books by William Morris, H. G. Wells, Edward Bellamy and Jack London.

In 1915 Wintringham he took the history entrance exam for Brasenose College, Oxford University. He did so well he was awarded the Brackenbury Scholarship for Balliol College. Later, he wrote: "When the Great War came I was torn between a half-understood idealist socialism and this fierce interest in fighting." However, he eventually decided that he would take part in the First World War. He enlisted on his 18th birthday and on 5th June 1916 he joined the Royal Flying Corps.

As a result of poor eyesight he was not allowed to fly aircraft. Instead he became a mechanic and dispatch rider attached to a balloon corps. He was sent to the Western Front where his "job was to pick up and deliver to base information about enemy artillery placements and trench lines contained in pouches that had been thrown out of the balloons."

In 1918 Wintringham was arrested and charged with mutiny. He was recovering in hospital from a serious bout of influenza when some of the men decided to walk into the local town and find some women. The charge was later reduced to "absent without a pass" and the sentence was a fine of six days' pay."

In November 1918 Wintringham was riding his motorbike near Mons at night when he crashed onto a railway line. He suffered severe concussion and spent several weeks in hospital. When he finally left the armed services he returned to Balliol College to study history. Two of his fellow students were Andrew Rothstein and Ralph Fox. In June 1920 Wintringham obtained his BA in Modern History.

His uncle, Tom Wintringham, a member of the Liberal Party, was elected to the House of Commons in 1920. The following year he died and his wife Margaret Wintringham, a former member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), was invited by the Louth Liberal Party to replace him as its candidate. In the subsequent by-election she was successful and became the second woman to sit in Parliament (Nancy Astor had been elected in 1919).

After leaving university Wintringham became a journalist specializing in military affairs. He visited Moscow where he met John Reed. He wrote for several newspapers and magazines and established the journal The Left Review.

In 1921 he joined the Inner Temple. His biographer, Hugh Purcell, wrote in Last English Revolutionary (2004): "A contemporary photograph of Tom fits the image of left-wing barrister. An idealistic-looking young man, informally dressed in a tweed jacket rather than suit, he looks directly at the camera; at ease with it and himself, clear features above a firm jaw and below a receding hair-line."

Like many former soldiers, Wintringham became angry about the large-scale unemployment that followed the First World War. In November 1921 a vast demonstration of 25,000 unemployed soldiers marched on the Cenotaph to place a wreath inscribed: "From the living victims - the unemployed - to our dead comrades who died in vain." The men wore pawn tickets instead of medals on their lapels.

In 1922 Wintringham met Elizabeth Arkwright, who was a founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. At first she rejected his advances. On 27th May 1923 she wrote: "I shall begin right away by telling you one reason why I so much want to wait a little. It's such a short time since I was in love with another comrade, who did not love me. I determined I would fall out of love with him quickly and, as a matter of fact, I have. But an emotional crisis leaves one dazed."

The following week Elizabeth wrote: "I do love you dear Tom, my self-doubt and hesitation are melting away so fast." Soon afterwards she arranged to stay the night with Wintringham: "Do I have to bring a nightdress? I look much better in pyjamas!" Later she wrote: "I am making some silk pyjamas. I'm going to make them without any buttons because it's so much easier; but that wouldn't do for you would it!?" The couple were married in 1923.

According to his autobiography, Wintringham joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1923. In June of that year he was left in charge of the Workers' Weekly and Labour Monthly when the entire executive of the CPGB was summoned to Moscow to discuss the future of the party.

Wintringham worked closely with Rajani Palme Dutt in the production of these publications. On 15th February 1924 he explained the way it worked: "The old style of Labour journal consists of long articles and a few notes from branches and committees, with unconnected propaganda notes filling up the odd spaces... I only spend one twentieth of my time writing. The rest is reading, sorting, combining and condensing the letters we get... I reckon in the first year we used a total of 1,149 letters, news reports and cuttings sent to us by workers."

Tom Wintringham had a reputation as a great womanizer and in 1925 he left Elizabeth Arkwright for another woman. Wintringham's biographer, Hugh Purcell, wrote in Last English Revolutionary (2004): "He tarnished his political career by a private scandal, thus setting a precedent he was to follow more than once in the years ahead. Although he had only been married for two years, he separated from Elizabeth and carried on a passionate but short-lived affair with another member of the Party." After coming under pressure from the leadership of the Communist Party of Great Britain Wintringham returned to Elizabeth.

On 4th August 1925, Wintringham and 11 other activists, Jack Murphy, Wal Hannington, Ernie Cant, Harry Pollitt, John R. Campbell, Hubert Inkpin, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, William Gallacher and Tom Bell were arrested for being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain and charged with violation of the Mutiny Act of 1797.

Tom Bell explained: "The indictment against the twelve read as follows: That between 1 January, 1924, and 21 October, 1925, the prisoners had: 1. Conspired to publish a seditious libel. 2. Conspired to incite to commit breaches of the Incitement to Mutiny Act, 1797. 3. Conspired to endeavour to seduce persons serving in His Majesty's forces to whom might come certain published books and pamphlets, to wit, the Workers' Weekly, and certain other publications mentioned in the indictment, and to incite them to mutiny." It was believed that the arrests was an attempt by the government to weaken the labour movement in preparation for the impending General Strike.

Harry Pollitt, Ernie Cant, Tom Wintringham, Albert Inkpin; (Front Row)

John R. Campbell, Arthur McManus, William Rust, Robin Page Arnot, Tom Bell.

The Communist Party of Great Britain decided that William Gallacher, John R. Campbell and Harry Pollitt should defend themselves. Tom Bell added: "their speeches were prepared, and approved by the Political Bureau (of the CPGB). To challenge the legality of the proceedings Sir Henry Slesser was engaged to defend the others. During the trial Judge Swift declared that it was "no crime to be a Communist or hold communist opinions, but it was a crime to belong to this Communist Party."

John Campbell later wrote: "The Government was wise enough not to rest its case on the activity of the accused in organising resistance to wage cuts, but on their dissemination of “seditious” communist literature, (particularly the resolutions of the Communist International), their speeches, and occasional articles... Five of the prisoners who had previous convictions, Gallacher, Hannington, Inkpin, Pollitt and Rust, were sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment and the others (after rejecting the Judge’s offer that they could go free if they renounced their political activity) were sentenced to six months."

Tom Wintringham, Jack Murphy, Ernie Cant, John R. Campbell, Arthur McManus, Robin Page Arnot, and Tom Bell was released from Wandsworth Prison at 8.15 a.m. on 11th April 1926 and was met by Elizabeth Wintringham and Rose Cohen. According to Rajani Palme Dutt: "Workers tramped from districts in every direction from the early hours of the morning, even fifteen miles through the London streets. Banners had been constructed bearing slogans of the fight, demanding the release of the remaining five prisoners and unity behind the miners... The drama reached its culmination outside the prison gates. The released Communist leaders shouted greetings through megaphones to those still imprisoned within. The cheers of 25,000 workers and the singing of the Internationale pierced the prison walls. The police took names and addresses of the tableaux actors and issued summons. Mounted police drove into parts of the procession causing injury."

In 1926 Elizabeth and Tom Wintringham moved to 51 Wilson Road in Camberwell Green. Soon afterwards Elizabeth heard that she had passed the LRCP and MRCS exams and could now practise as a doctor. However, she did not find work and the couple existed on Tom's salary as a journalist on Workers' Weekly. Later, he became editor of The Worker, the official journal of the National Minority Movement, a Communist-led united front within the trade unions.

On 13th November 1927 their first son was born, Robin, named after their friend Robin Page Arnot. He died in his cot six months later. After moving to 20 Warren Avenue, East Sheen, their second son, Oliver, was born on 18th March 1929. Later that year Tom began an affair with Millie, a worker with the CPGB. In 1930 he deserted Elizabeth and Oliver to live with Millie.

On 1st January 1930, the Communist Party of Great Britain launched its newspaper, The Daily Worker. Tom Wintringham was appointed chairman of the Utopia Press, the publishers of the newspaper. He later recalled: "I had to pay printers with I.O.U.s, stave off landlord and business, keep the paper going in spite of a mountain of debts for paper and machinery." After only a few weeks the circulation had dropped from 45,000 to 39,000 and the newspaper was losing £500 a week.

In September 1931, Tom's third child, Lesley was born. Elizabeth wrote to Tom during this period: "I know you are having a mouldy time. Don't think of me as someone you have hurt, but I am so utterly sure that Millie cannot give you more than passing happiness that it terrifies me to think of you tying yourself up only to have this sort of experience again." However, in May 1932, Tom returned to Elizabeth and as a result Millie was forced to put Lesley into a children's home.

Over the next few years Wintringham became according to one critic he was "the leading Marxist expert on military affairs at present writing in English". He wrote a series of pamphlets including War and the Way to Fight Against It (1932) and Air Raid Warning (1934). In 1935 Wintringham published The Coming World War. The following year he became Military Correspondent of the Daily Worker and wrote a series of articles on modern warfare. His next book was Mutiny: A Survey of Mutinies from Spartacus to Invergordon (1936).

During this period Wintringham supplemented his income by working part-time for Russian Oil Products, a company that was selling oil to the United Kingdom. In reality, the company was used to provide funds from the Soviet Union to key members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In August 1936 Harry Pollitt arranged for Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the CPGB during the Civil War. While in Barcelona in September he met an American journalist Kitty Bowler. She later recalled: "I wandered over to the cafe Rambla feeling desolate and forlorn. Like the story book waif, who peeks through frosted panes at the happy families gathered round the fireside, I eyed the little group at a corner table... All conversation stopped. Blankly and coldly they looked at me as only the English can. Then a soft-voiced bald man touched my arm: "You must join us." Soon afterwards Wintringham began an affair with Bowler.

While in Spain Wintringham developed the idea of a volunteer international legion to fight on the side of the Republican Army. He wrote: "You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in."

On 10th September 1936 Wintringham wrote to Harry Pollitt that he had arranged for Nat Cohen, a Jewish clothing worker from Stepney, to establish "a Tom Mann centuria which will include 10 or 12 English and can accommodate as many likely lads as you can send out... I believe that full political value can only be got from it (and that's a lot) if its English contingent becomes stronger. 50 is not too many."

Maurice Thorez, the French Communist Party leader, also had the idea of an international force of volunteers to fight for the Republic. Joseph Stalin agreed and in September 1936 the Comintern began organising the formation of International Brigades. An international recruiting centre was set up in Paris and a training base at Albacete in Spain.

Sid Avner, Nat Cohen, Ramona, Tom Wintringham, George Tioli, Jack Barry and David Marshall.

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, who was with Tom Wintringham at the time, later pointed out that Kitty Bowler "was a neat, active, progressive, American girl who had nipped across from France to see what was going on and maybe to make a name for herself." Wintringham's biographer, Hugh Purcell, wrote in Last English Revolutionary (2004): "While Tom and Kitty were falling in love they were also exploiting each other. She used him to guide her apprentice journalism; he used her as unofficial secretary and messenger."

In October 1936, Wintringham joined the International Brigades at their base in Albacete. He wrote to Kitty that the medical commission had marked him fit for service and that he would probably go to the Officers' Training School as an instructor but was keen to get to the front-line as soon as possible. His first job was as machine-gun instructor to the XI and XII Battalions. He told Kitty: "I'm blooming with uppishness at having vicious little guns to learn and handle... Think of me with my devil-guns. There's a certain exact, free of frills sensible beauty about a good piece of engineering."

Kitty Bowler wrote to Tom: "You took a somewhat undirected little lost girl and made a person of her. I love you, love you, all of you, your long tall body, your sweet steadying voice, your brains and good sense mixed with good emotion." Tom replied: "You know a good deal about giving a man a good time, and then some! The total effect on morale of my 24 hours leave was A1 Magnificent. I'm on top of the world."

Ralph Bates, a writer based in Spain, sent a highly critical report to Harry Pollitt about Wintringham and his relationship with Kitty Bowler. "Everyone here was very disappointed with Comrade Wintringham. He showed levity in taking a non-Party woman in whom neither the PSUC nor the CPGB comrades have any confidence to the Aragon front. We understand this person was entrusted with verbal messages to the Party in London. We are asked to send messages to Wintringham through this person rather than the Party headquarters here. The Party has punished members for far less serious examples of levity than this."

Kitty Bowler arrived back in London with a message from Tom Wintringham. Kenneth Sinclair Loutit was in the CPGB offices at the time: "She bounced in as the dawn, looking as bright as a new dollar and bringing an unaccustomed waft of Elizabeth Arden fragrance through the dusty entrance." Bowler asked for Harry Pollitt but he was out and was instead seen by Rajani Palme Dutt and John Campbell. Loutit commented: "She saw Pollitt later but the damage was done. Tom had sent back a bourgeois tart - a great talker, some said she clearly had Trotskyite leanings... It must not be forgotten that Tom had a wife of deadly respectability and unimpeachable Marxist propriety."

Kitty claimed that she asked Harry Pollitt to send Wintringham home. According to Kitty he told her to "tell him to get out of Barcelona, go up to the front line, get himself killed to give us a headline.... the movement needs a Byronic hero." However, many people who knew Pollitt well claim that he would never had said such a thing.

When Kitty Bowler returned to Spain she joined the PSUC English-speaking radio service in Barcelona. In December 1936 she joined the UGT and wrote to her mother: "I've gotten in with the editor of a Spanish newspaper and am getting all sorts of inside news and rushed around in cars." Her new contacts resulted in being given an assignment from The Toronto Star.

Wintringham wrote to Millie explaining that his relationship with her was over. She continued to write to him and on 23rd January 1937 she reported "Harry... told me that the News Chronicle London office had received a report that you had been killed in action near Madrid... He had been very torn about giving me the news but thought it best." However, she found out from Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland that the story was untrue.

In January 1937 Kitty Bowler travelled to Albacete where she was detained and interviewed by André Marty. "Behind a rolltop desk sat an old man with a first class walrus moustache. He was sleepy and irritable and had pulled a coat on over his pyjamas. He reminded me of a petty French bureaucrat. Perhaps that was just as well. To my surprise my mass of Spanish papers did not interest him in the least. Even my U.G.T. card and pass were thrown back in my face, contemptuously. My past was all that interested him, but I was sure it would all be cleared up in the morning when Mac and Tom came over. ... At the end of an hour he read out the charges and they shocked me out of my certainty. 1) Travelled from Albacete to Madrigueras by truck without a pass. 2) Penetrated into a military establishment. 3) Interested yourself into the functioning (bad) of machine guns. 4) Visited Italy and Germany in 1933. Therefore you are a spy."

Tom Wintringham attempted to protect Kitty Bowler by contacting André Marty. He then told her: "You impressed Marty as very, very strong, very clever, very intelligent. Although this was said as a suspicious point against you - women journalists should be weak and stupid - I got a jump of pride from these words." After being interviewed for three days and nights Kitty was expelled from Spain as a spy.

Wintringham was given the rank of captain and on 29th January 1937 he wrote to his mother: "I carry now a silver-handled walking-stick... In a few days I get a real officer's uniform, Sam Browne belt and all. But the real pleasure I get is teaching and learning from men I like and respect."

On 6th February, 1937, Wintringham became the commander of the British Battalion of the International Brigade. The commissar for English-speaking volunteers in the battalion, Peter Kerrigan, wrote to Wintringham about the standard of the soldiers under their control: "Some lads have no desire to serve in the army. All recruits must understand they are expected to serve. Tell them; this is a war and many will be killed. This should be put brutally, with a close examination of their hatred of fascism. A much greater discipline is needed. Recruits must be told there is no guarantee of mail and the allowance is only three pesetas a day."

Wintringham agreed with Kerrigan and sent a message to Harry Pollitt: "About ten percent of the men are drunks and flunkers. I can't understand why you've sent out such useless material. We call them Harry's anarchists."

After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February.

General José Miaja sent three International Brigades including the Dimitrov Battalion and the British Battalion to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. On 12th February, at what became known as Suicide Hill, the Republicans suffered heavy casualties. Tom Wintringham was forced to order a retreat back to the next ridge. The Nationalist then advanced up Suicide Hill and were then routed by Republican machine-gun fire.

On the right flank, the Nationalists forced the Dimitrov Battalion to retreat. This enabled the Nationalists to virtually surround the British Battalion. Coming under heavy fire the British, now only 160 out of the original 600, had to establish defensive positions along a sunken road.

During the afternoon Jason Gurney had been ordered by Wintringham to reconnoitre to the south of the sunken road: "I had only gone about 700 yards when I came across one of the most ghastly sights I have ever seen. I found a group of wounded (British) men who had been carried to a non-existent field dressing station and then forgotten. There were about fifty stretchers, but many men had already died and most of the others would be dead by morning. They had appalling wounds, mostly from artillery. One little Jewish kid of about eighteen lay on his back with his bowels exposed from his navel to his genitals and his intestines lying in a ghastly pinkish brown heap, twitching slightly as the flies searched over them. He was perfectly conscious. Another man had nine bullet holes across his chest. I held his hand until it went limp and he was dead. I went from one to the other but was absolutely powerless. Nobody cried out or screamed except they all called for water and I had none to give. I was filled with such horror at their suffering and my inability to help them that I felt I had suffered some permanent injury to my spirit."

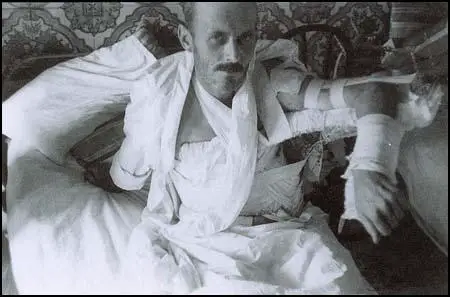

On 13th February, 1937, Wintringham was hit in the thigh while trying to organise a bayonet charge. Fred Copeman later commented that George Aitken and himself found Wintringham sitting behind an olive tree: "Well, we knew he shot himself." This is refuted by Aitkin who confirmed that he had been shot by the enemy.

The Daily Mail claimed on 20th February 1937 that many of the so-called volunteers had been press-ganged into the British Battalion and that at Madrigueras those who did not want to fight "were lined up and shot; the remainder like cattle were then driven to slaughter... commanded by an Englishman named Wintringham." As a result of this article, Wintringham later won a libel action against the newspaper.

Elizabeth Wintringham wrote to Tom in hospital: "When I tell him (Oliver) that he must be proud of his father fighting the fascists he clenches his fists and looks so serious and fierce I could weep." She then added: "You are indeed having a lot of varied experience, but shall I know you when you come back? I shall be most anxious to make your acquaintance you may be sure."

Kitty Bowler visited him in Pasionaria Military Hospital and discovered he was suffering from typhoid and a form of septicaemia. Patience Darton, a nurse with the International Brigades, later commented: "I poked around with a pair of scissors and found he had a lot of pus in his wounds which had been sewn up too tightly. And that was it; he got better very quickly."

Elizabeth Wintringham wrote to Kitty to thank her for looking after Tom. "How perfectly splendid you have been! Is Tom sensible at all, or rambling all the time? If it's possible please give him my love and Oliver's. If he seems inclined to worry about Millie and Lesley assure him they are being looked after. You may know who they are. I shall hope very much to meet you someday before long."

Charlotte Everett Bowler was less pleased with her daughter looking after Tom. She wrote: "It's all very charming and delightful for you; you gain almost everything. For my very dear child it's pretty tragic any way you look at it. I resent her giving her all - her mind, body and spirit - on such insecure grounds. Naturally I am distressed."

Tom replied: "I owe my life to your daughter, and a great deal more than just going on living... But there is very little I can say to reassure you because security does not exist. If I could have married Kitty I would have done so; if I can, I will. But better this might be in the future, rather than tie her to a blind or crippled husband."

While Tom was in Pasionaria Military Hospital he was visited by William Gallacher who had an order from the Communist Party of Great Britain: "The Party Order that I should leave Kitty was delivered to me by a very embarrassed Bill Gallacher while she was still nursing me through typhoid before I was strong enough even to stand."

Kitty Bowler was arrested by the Comintern police on 2nd July 1937 and she was expelled from Spain. She moved back to the United States. On 17th July 1937 Tom wrote: "My dear, the party, our party, yours and mine, is sometimes hard on individuals. But look at the job of work it does as a whole and there's nothing like it on earth or ever has been."

Tom Wintringham rejoined the XV Brigade on 18th August 1937 as a staff officer. He was immediately sent to the Aragon front and during the Battle of Belchite on 24th August he was shot in the shoulder while attempting to capture Quinto. He wrote to Kitty: "A bullet through the soldier, cracking a bone or so. Lost a lot of blood. I love you. Being away from you hurts more than silly bullets."

Dr Alex Tudor-Hart, a member of the CPGB who was providing medical care for the British Battalion, told him that his shoulder bone had splintered and this extended almost down to his elbow. This became infected and after two operations in Spain he was sent home to England. Kitty Bowler immediately left the United States and the two of them set-up home in a flat in York Street, London.

Tom's younger sister, Margaret, wrote a letter to Kitty: "I'm afraid I think it's rather a pity that you have come to London. I have grown to love and admire Elizabeth - I think she is a very good person... I know that the Party was pretty annoyed with him some time ago and the Millie-Elizabeth situation has been a source of embarrassment to Harry Pollitt. One or two people back from Spain have spoken of Tom's affairs as a joke, which is intolerable. So you see I must take sides against you."

Margaret Wintringham also wrote to Tom about his behaviour: "You simply can't get away with all this irresponsibility. Granted you have to abandon two sets of families, you might at least spare them minor anxieties. You could spare Elizabeth the small humiliation of ringing up the hospital and being asked if she would like to speak to Mrs Wintringham. You know you have a strong faculty for inspiring affection but I repeat, you can't get away with things like this."

Tom refused to go back to live with Elizabeth Wintringham and continued to live with Kitty Bowler at 30 Arundel Square, London. He also began work on English Captain, a book on his experiences of the Spanish Civil War.

Convinced that Britain would be invaded by Nazi Germany Wintringham advocated that trenches should be dug in the parks of all the big towns. The government agreed and on 25th September 1938 the Air Raid Precaution Service (ARP) were mobilised and trenches were established all over the country.

At a meeting of the Comintern in March 1938, André Marty confirmed that Kitty Bowler was a "Trotskyite spy". Wintringham was contacted and told that if he did not leave Bowler he would be expelled from the Communist Party of Great Britain. According to a Politburo meeting on 18th May 1938: "He (Wintringham) refused to accept discipline in relation to a personal question not considered to be in the interests of the Party." The case was put into the hands of Rajani Palme Dutt who decided that Wintringham should definitely be expelled from the CPGB. The Daily Worker printed the verdict on 7th July 1938.

Wintringham received support from people such as Bob Stewart and Harry Pollitt but they were unable to change the mind of Rajani Palme Dutt who carried out the orders of Joseph Stalin and the Soviet government.

As Hugh Purcell has argued: "Why did the CPGB agonise for so long and then take this extreme decision when Kitty was clearly not a Trotskyite spy and Tom was a senior member of the Party who had narrowly escaped death on its behalf in Spain? The answer lies in the reign of terror in Russia. Senior members of the Party were petrified they might lose their jobs or even their lives if they showed the slightest taint of Trotskyism. At the very time that Tom was fighting for his professional life his old friend Rose Cohen was waiting to be shot in Moscow. Her husband, Max Petrovsky, had been arrested the previous year as a wrecker (he had known Trotsky) and all British Communists who knew him had to make statements."

The leaders of the CPGB remained loyal supporters of Joseph Stalin in his attempts to purge the followers of Leon Trotsky in the Soviet Union. Harry Pollitt described it as "a new triumph in the history of progress". Rajani Palme Dutt used his journal, the Labour Monthly, to defend the Great Purge. As Duncan Hallas pointed out: "He repeated every vile slander against Trotsky and his followers and against the old Bolsheviks murdered by Stalin through the 1930s, praising the obscene parodies of trials that condemned them as Soviet justice".

At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". He added: "Every responsible position in the Party must be occupied by a determined fighter for the line." Bob Stewart disagreed and mocked "these sledgehammer demands for whole-hearted convictions and solid and hardened, tempered Bolshevism and all this bloody kind of stuff."

William Gallacher agreed with Stewart: "I have never... at this Central Committee listened to a more unscrupulous and opportunist speech than has been made by Comrade Dutt... and I have never had in all my experience in the Party such evidence of mean, despicable disloyalty to comrades." Harry Pollitt joined in the attack: "Please remember, Comrade Dutt, you won't intimidate me by that language. I was in the movement practically before you were born, and will be in the revolutionary movement a long time after some of you are forgotten."

John R. Campbell, the editor of the Daily Worker, thought the Comintern was placing the CPGB in an absurd position. "We started by saying we had an interest in the defeat of the Nazis, we must now recognise that our prime interest in the defeat of France and Great Britain... We have to eat everything we have said."

Wintringham completely disagreed with the Communist Party of Great Britain about the Second World War. He argued that the new party line was "disastrous, wrong, non-Marxist, contrary to the interests of the working-class and of the revolution." As Hugh Purcell has pointed out: ""He disliked increasingly the subservience of the Communist Party of Great Britain to the Comintern, in effect to Russian foreign policy, and he became vitriolic when the Party stayed out of World War Two after Stalin's peace pact with Hitler in the summer of 1939."

Tom Hopkinson recruited Wintringham to work for the Picture Post. He also wrote a regular column for the Daily Mirror, Tribune and the New Statesman. This gave him a readership of several million. He also wrote several pamphlets on the war effort including New Ways of War (1940), Freedom is Our Weapon (1941) and Politics of Victory (1941).

In New Ways of War he wrote: "Knowing that science and the riches of the earth make possible an abundance of material things for all, and trusting our fellows and ourselves to achieve that abundance after we have won, we are willing to throw everything we now possess into the common lot, to win this fight. We will allow no personal considerations of rights, privileges, property, income, family or friendship to stand in our way. Whatever the future may hold we will continue our war for liberty."

Wintringham "believed that war provided the best opportunity for revolution and that a revolution was necessary for fascism to be defeated." George Orwell agreed with him: "We are in a strange period of history, in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary." Both men had been deeply influenced by their experiences of fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

In October 1939, Winston Churchill suggested to Sir John Anderson, the head of Air Raid Precautions (ARP), that a Home Guard of men aged over forty should be formed. Anderson agreed with Churchill's suggestion but it was not until the German Army had launched its Western Offensive that action was taken and on 14th May, 1940, Anthony Eden appealed on radio for men to become Local Defence Volunteers (LDV). In the broadcast Eden asked that volunteers should be aged be aged between 40 and 65 and should be able to fire a rifle or shotgun. By the end of June nearly one and a half a million men had been recruited.

Wintringham wrote several articles where he argued that the Home Guard should be trained in guerrilla warfare. Tom Hopkinson and Edward Hulton came up with the idea private training school for the Home Guard. On 10th July 1940, Wintringham was appointed as director of the Osterley Park Training School at Isleworth, Middlesex. In the first three months he trained 5,000 in the rudiments of guerrilla warfare.

In 1940 Wintringham wrote a 20,000 word pamphlet entitled How to Reform the Army. Over the next few months over 10,000 copies were sold and he was consulted by Sir Ronald Adam, the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir John Brown, the Deputy Adjutant-General and Major General Augustus Thorne, the Commander of the Brigade of Guards.

At the beginning of Second World War, Kitty worked for left-wing newspapers such as the People's Independent. In 1939 Elizabeth Wintringham and her son Oliver left London to live in Derbyshire. Oliver attended Abbotsholme School. On 12th February 1940 Elizabeth petitioned for divorce.

Their friends during this period included Storm Jameson, Naomi Mitchison, Stephen Swingler and Pearl Binder. However, Anne Swingler pointed out: "She (Kitty) certainly didn't like pretty young girls around. She was thin, with wild dark hair and an awkward manner. I thought she was scatty, an endless talker, but bossy too. She was very possessive of Tom. People avoided her." Anne liked Tom a great deal: "He spoke with such authority but he was gentle and charming too. Quite a lady's man! And he thrived on women's company."

On 20th May 1940 Wintringham became the Military Correspondent of the Daily Mirror. He continued to write for other publications. One article published in the Picture Post on 15th June that gave practical instructions for a people's war to resist invasion was bought by the War Office which printed off 100,000 copies and distributed them to Home Guard units.

The War Office became concerned about the activities of the Osterley Park Training School. The Inspector's Directorate of the Home Guard reported in July 1940: "While approving of the school in principle, the London District Assistant Commander did not think the Instructors were of a suitable type because of communistic tendencies. On 10th September General Pownall informed the Inspector's Directorate that "the school at Osterley was gradually being taken over by the War Office." In the spring of 1941 Wintringham was dismissed from his post as director of the training school.

Wintringham published People's War in 1942. He argued that a modern people's war combines "guerrilla forces behind enemy lines with a blitzkrieg striking force." In another pamphlet, Freedom is Our Weapon, Wintringham wrote: "If we are able to achieve the making of a people's army, we can be sure that the men will come back determined to achieve and capable of achieving for themselves their own homes for heroes, their own society linking liberty, agreement and co-operation."

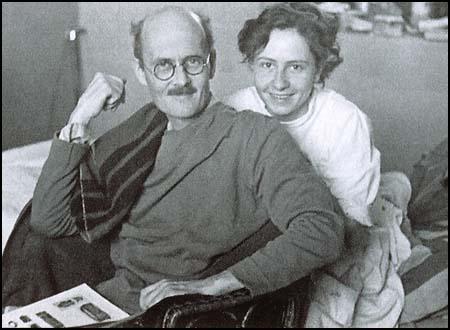

Tom Wintringham married Kitty Bowler at Dorking Registry Office on 25th January 1941. Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, a friend since the Spanish Civil War, was the main witness.

J. B. Priestley and a group of friends established the 1941 Committee. One of its members, Tom Hopkinson, later claimed that the motive force behind the organization was the belief that if the Second World War was to be won "a much more coordinated effort would be needed, with stricter planning of the economy and greater use of scientific know-how, particularly in the field of war production." Wintringham joined and so did Edward G. Hulton, Kingsley Martin, Richard Acland, Michael Foot, Peter Thorneycroft, Thomas Balogh, Richie Calder, Tom Wintringham, Vernon Bartlett, Violet Bonham Carter, Konni Zilliacus, Tom Driberg, Victor Gollancz, Storm Jameson, David Low, David Astor, Thomas Balogh, Richie Calder, Eva Hubback, Douglas Jay, Christopher Mayhew, Kitty Bowler and Richard Titmuss.

In December 1941 the committee published a report that called for public control of the railways, mines and docks and a national wages policy. A further report in May 1942 argued for works councils and the publication of "post-war plans for the provision of full and free education, employment and a civilized standard of living for everyone."

On 25th June, 1942, the Common Wealth Party supported Tom Driberg, the independent candidate that stood at a by-election at Maldon. Driberg won a sensational victory, reducing the Conservative vote by over 20%. Later that year Richard Acland and J. B. Priestley and other members of the 1941 Committee established the socialist CWP. The party advocated the three principles of Common Ownership, Vital Democracy and Morality in Politics.

Kitty Bowler was on the National Committee of the Common Wealth Party (CWP) and during this period came into conflict with Richard Acland. He accused her of having a "more chaotically disorderly brain than anyone I've ever met... you are wholly incapable of holding an organised part in any discussion or argument." Kitty replied that the CWP "is disintegrating because of attempts to turn it into an autocratic pseudo-religious body with fascist tendencies."

In 1942 the Common Wealth Party decided to contest by-elections against Conservative candidates. The CWP needed the support of traditional Labour supporters. Wintringham wrote in September 1942: "The Labour Party, the Trade Unions and the Co-operatives represent the worker's movement, which historically has been, and is now, in all countries the basic force for human freedom... and we count on our allies within the Labour Party who want a more inspiring leadership to support us." Large numbers of working people did support the SWP and this led to victories for Richard Acland in Barnstaple and Vernon Bartlett in Bridgwater.

Tom Wintringham decided to stand for the Common Wealth Party in the safe Conservative seat of North Midlothian. People who campaigned for him included H. G. Wells, J. B. Priestley, H. N. Brailsford, Sybil Thorndike, Naomi Mitchison and Kitty Bowler. The by-election took place on 5th February 1943 and Wintringham won 48% of the vote but lost to the Solicitor General for Scotland, Sir David King Murray by 869 votes.

Over the next two years the CWP also had victories in Eddisbury (John Loverseed), Skipton (Hugh Lawson) and Chelmsford (Ernest Millington). George Orwell wrote: "I think this movement should be watched with attention. It might develop into the new Socialist party we have all been hoping for, or into something very sinister." Orwell, like Kitty Bowler, believed that Richard Acland had the potential to become a fascist leader.

Negotiations went on between the CWP and the Labour Party about the 1945 General Election. Richard Acland demanded the right to contest 43 selected Conservative-held seats without opposition from Labour in return for not contesting all other constituencies. After this offer was rejected, Wintringham met with Herbert Morrison, and suggested this be lowered to "twenty middle-class Tory seats". Morrison made it clear that his party was unwilling to agree to any proposal that involved Labour candidates standing-down.

Tom Wintringham was commissioned by Victor Gollancz to write a book, Your MP. The book sold over 200,000 copies and was a best-seller during the 1945 general election campaign. The book contained an appendix detailing how 310 Conservative MPs voted in eight key debates between 1935 and 1943.

Wintringham decided to stand as the Common Wealth Party candidate in Aldershot. He persuaded the Labour Party candidate, Tom Gittins, not to stand. Wintringham launched a strong political attack on Oliver Lyttleton, the Conservative candidate. He pointed out that before the Second World War Lyttleton was a director of the German metal combine Metallgesellschaft that was arming the German Army.

Wintringham halved the Tory vote in the 1945 General Election but still lost by 14,435 votes to 19,456. The Labour Party ended up with 393 seats, whereas only one of the CWP twenty-three candidates was successful - Ernest Millington at Chelmsford, where there was no Labour contestant. Two of his former friends in the Communist Party of Great Britain, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin, also won seats in the election.

After the war Tom and Kitty lived in Pear Trees, at Brick End, Broxted. On 26th January 1947, Kitty gave birth to Benjamin Rhys Wintringham. In 1948 they moved to Edinburgh. Tom continued to work as a journalist and their income was supplemented by a trust fund that had been set-up in New York City by Kitty's family. Tom wrote to his son Oliver Wintringham: "Happiness, I feel superstitiously, should never be mentioned in a world such as this that you inherit. Then sometimes it may creep up on you without noticing you are there; and if you politely do not stare at it, may remain about the place."

Tom became radio critic of the New Statesman in 1946. He also appeared on the radio in BBC's The Critics programme. He also wrote regular articles for the Picture Post.

Tom Wintringham died while helping with the harvest on his sister's farm at Searby Manor in Lincolnshire on 16th August 1949. The post-mortem showed that Tom died of a ruptured aneurism of the right coronary artery. Kitty wrote to her friend, Rhys Caparn: "When they finally allowed me to go back and see him after the post mortem. I went to see his hands, hands don't die. And then it was the face that was so wonderful - not my private Tom, but all the fine strength of him - the man who could and did - and so many believed would do again and he was about ready to - could lead and inspire men." The funeral took place at Leeds Crematorium three days later.

Primary Sources

(1) Tom Wintringham, New Ways of War (1940)

I was born in 1898 in a house of solid Victorian brick in a town of solid Victorian prosperity. The prosperity was not elegant; in fact, it stank a bit of fish. I absorbed from my parents, nonconformists in religion, liberal in their outlook on life, a tradition of non-political radicalism.

(2) Tom Wintringham, The Workers' Weekly (15th February, 1924)

The old style of Labour journal consists of long articles and a few notes from branches and committees, with unconnected propaganda notes filling up the odd spaces... I only spend one twentieth of my time writing. The rest is reading, sorting, combining and condensing the letters we get... I reckon in the first year we used a total of 1,149 letters, news reports and cuttings sent to us by workers.

(3) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

For me it was lucky that someone called Tom Wintringham got on to our train at Paris. He became a friend and stayed so for the rest of his life. At the end of the Great War he had been one of the millions demobilized who were not ready to return to the slot in Society from which they had come. His father had been a well-to-do Quaker solicitor in Hull, but his son had not been a pacifist. In 1918 he had ended up as a dispatch-rider. In 1920, once again a civilian, he got onto his faithful Douglas and motorcycled to Moscow. When he came back to England he settled into London's left wing intellectual life. His reasons for being on the train were not clear but, he was known as the man from the Daily Worker. His subsequent career shows him as a bit more than that. He helped to form the fist British Unit in the International Brigade. He became the military inspiration of the Home Guard in 1940 and went on, with Sir Richard Rees to found the Commonwealth Party which won a couple of Parliamentary seats on a social-democratic basis. In August 1936 at the Spanish frontier it was me whom Tom Wintringham was inspiring; only a short time later on the Aragon front it was from him that I was to learn my first lessons under fire. You do not forget someone who shows you how to stay alive.

(4) Tom Wintringham, The English Captain (1939)

I believed in the idea of an international legion. Militias can do a lot. But a larger-scale example of military knowledge and discipline, and larger-scale results, are needed too. You have to treat the building of an army as a political problem, a question of propaganda, of ideas soaking in. You need things big enough to be worth putting in the newspapers.... Surely a big-scale, well-placarded example was necessary?

(5) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, letter to David Fernbach (1978)

Tom was carrying a knap-sack and wore a trench coat; the sort of stuff that Millets sold in their army surplus stores. He looked battered but had a good smile and a small subaltern moustache below his bald head. His approach to me was characteristic, direct, friendly, pragmatic, constructive. "How can your presence be explained?" I asked. "Look," said Tom, "the Party as you saw in Paris is the brain, heart and guts of the Popular Front and it's even more so in Spain. Unless the unit is right with the Party you'll be lost." He went on to suggest that his party affiliations should be neither concealed nor advertised...

He (Wintringham) was helpful and kind in great things and small. To be with a warmly human Marxist who was also a cool soldier made it possible for me possible for me to find the beginning of the path and I count him one of the best friends I ever had. I understood exactly what Kitty saw in him. He still carried some of the hubris of that gallant generation that bore the weight of 1914-18.

(6) Tom Wintringham, The English Captain (1939)

Barcelona, largest city in Spain and capital of Catalonia, is colour, noise, heat, dust, violent traffic and quick-moving people. Many of the men carry rifles slung on their backs, slung all ways; they wear cotton sandals, rope-soled, workmen's overalls of blue, brown and khaki. They march in groups of ten and sections of thirty, in centurias and columns, shuffling a little because of their sandals, in light smooth quick-step. They sing a little, salute often, with a raised clenched fist. Men and women crowd and climb to see them, cheer, clap. Banners are carried in front of each unit: the red and black, diagonally divided, of the Anarchists, the red with white letters of the Socialists and Communists, the hammers and sickles of the P.O.U.M; and there are also orange-striped flags, sometimes with a white star inset on blue, Catalan nationalism, and the red-yellow-purple of the republic of Spain.

(7) Tom Wintringham, letter to his mother (29th January, 1937)

I carry now a silver-handled walking stick. I'm appointed to the English speaking battalion as "Capitaine adjoint-majeur". In a few days I get a real officer's uniform, Sam Browne belt and all. But the real pleasure I get is teaching and learning from men I like and respect, and who like me - comrades who have got "real faith and fire within us".

Good, too, to make real the game of manoeuvre I used to play - do you remember? - with counters or with matches, books for hills and pencils for rivers, all over the floors and desks of the Garden House. I can do this job.

(8) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

A few days later the first drip-dry cotton any of us had ever seen was hanging in the Grañen hospital garden. It belonged to an American free-lance journalist called Kitty. She dressed smartly and neatly in practical "sporty" clothes. She had come to have a look at us, because Tom Wintringham had told her that there was a good story waiting to be written on the Huesca front. She later became Kitty Wintringham; by 1938 their coming together was to result in Tom being expelled from the British Communist Party.

Tom's fault was maintaining personal relations with elements considered undesirable by the CPGB which dated from the very week of my baptism of fire. It was the arrival of Kitty that did it. Tom was only fifteen years older than me, but I had read very widely and was in some ways older than my own twenty three. This meant that we could talk together on a plane that helped us both. Tom's conclusions, after a few weeks of Spain, were clear-cut and definite. In war, as in boxing, amateurs can only win a fight against professionals by scoring a knock-out in an early round. In the case of Spain, the amateurs were not making a full-time job of fighting the enemy; they were taking time off for fighting each other. The rivalry of PSUC and the FAI was ruinous. The foreign volunteers were tragically amateur. Who could imagine that the Thaelmann Centuria Germans were from a great military nation? They had good morale, they were risking their lives, but their lines were a slum and all military initiative was left to the enemy. Tom wrote a paper in September 1936 suggesting that international volunteers must show real military expertise. To use foreign volunteers for their journalistic impact on non-Spanish public opinion might be politically useful, but such amateurs would not change the military position. He wanted the Central Committee of the British Communist Party to reach a mature appreciation of the military position because he thought that the working-class movement's current reaction to the Civil War was altogether lacking in realism.

For Tom Wintringham, the Popular Front should be showing professionalism in military matters. International military assistance should be as professional as was the medical assistance. He was asking for an International Brigade of ex-servicemen. He got Kitty to take his report back to King Street (the CPGB H/Q) where she was to put it directly into the hands of Harry Pollitt, the Secretary General of the British Communist Party. The risk of mailing it from Spain was certainly far too great, but the choice of Kitty as a courier for this 'high security' tract was in fact a tactical error. Kitty was a college-girl archetype - leggy with a swinging walk, bottom in and bust out even though she did not have much of either. Her quick-fire, clear, zesty, American speech came out of a neatly lipsticked mouth which was set in a young self-confident face. I suppose she was then just less than 30 years old. So Kitty hurtled back to London arriving at Victoria Station early one morning feeling pretty beat up. She wanted to do a good job for Tom. Her background told her that a beat-up girl does not get as good a hearing as one who looks on top of the world. For a good hearing in King Street in 1936 this was a wrong. Led by her mistaken intuition, Kitty went straight from Victoria Station to the Bond Street Elisabeth Arden and gave herself the works: sauna, full facial, hairdo, and no doubt put on a clean drip-dry swirly skirt.

On the top of her form, she took King Street by storm. She certainly laid them all flat, but with the wrong emotions. A month or so later I had her side of the tale; she said that only one person in King Street knew how to smile but he worked with a sour-puss. They were glad to get Tom's report, but they did not seem to want any discussion. She also had taken the chance to tell them that they ought to make better financial arrangements for Tom in Spain, as he was quite evidently short of money.

A secondary source later indicated to me that Tom's lawful wedded wife, a party-member of standing, had been in King Street on the morning that Tom's dispatch was delivered. Kitty's mere presence, to say nothing of her Elisabeth Arden aura, must have served to confirm all the earlier traveller's tales. In those days a certain greyness, a quakerish sobriety, an evident renunciation of the superfluous, was reckoned as becoming to females with Party links. Poor Kitty must have exemplified the very licentiousness of the class-enemy, the bourgeoisie. Tom had certainly chosen Kitty as courier because he knew that she would get there, through Hell or high-water, without fail. What he failed to see was that her appearance, and her frank drive, would serve to weaken the force of his dispatches. He had not yet come to grips with Stalinist mediocracy; a characteristic so well demonstrated by O'Donnel.

(9) Jason Gurney, Crusade in Spain (1939)

He (Tom) was a slim man of medium height, with large, round, steel-framed spectacles, a high-domed bald head and an academic stoop. He always wore a khaki beret, a shiny black mackintosh coat of vaguely military cut, riding breeches and high laced boots. The total effect suggested a motor-cyclist rather than a soldier. He was invariably pleasant, informal and unpretentious. I don't think that he really knew any more about military affairs than I did, but he was a completely sincere radical who did his best to be useful to the cause without any idea of personal aggrandizement.

His only apparent vice was a weakness for delivering long and tedious lectures on the Marxist theory of warfare, heavily larded with texts from Marx and Engels which were supposed to re-inforce the argument.

(10) Bill Alexander, British Volunteers for Liberty (1992)

Eleven men in all commanded the British Battalion in actual battle: Wilfred McCartney (writer, who had to return before any fighting), Tom Wintringham (journalist), Jock Cunningham (labourer), Fred Copeman (ex-navy), Joe Hinks (army reservist), Peter Daly (labourer), Paddy O'Daire (labourer), Harold Fry (shoe repairer), Bill Alexander (industrial chemist), Sam Wild (labourer), and George Fletcher (newspaper canvasser). All except Wintringham had the opportunity of showing their abilities in action before being given leadership. All of them had been involved in working-class, anti-fascist activities at home, and had been influenced by Communist ideas and activity, although only Wintringham had held responsible positions in the Communist Party itself. In Spain their beliefs were reinforced by struggle and experience. The majority had been manual workers, having left school at fourteen - the usual lot of most in those days, no matter how intelligent or able. Only McCartney, Wintringham and Alexander had been to university; all had experienced the difficulties and frustration of finding work in a period of heavy unemployment. Their anti-fascism was anchored in hatred of the class and social system in Britain.

(11) Frank Ryan, The Fifteenth Brigade (1938)

In Spain since August 1936, his first assignment was machine-gun instructor. Later he was appointed in command of the British Battalion and led it at Jarama. Wounded on his second day in the field, he was just convalescent when typhoid put him back for another a few months. After a period as instructor at an Officers' Training Camp, he rejoined the XV Brigade in August, as a staff-officer, only to be again wounded on his second day in action, during street-fighting in Quinto. To the regret of all with whom he has worked, and of all he has led, his wound incapacitates him from active service for an indefinite period.

(12) The Daily Worker (7th July, 1938)

The Control Commission of the Communist Party has recommended the exclusion of Tom Wintringham for refusal to accept a decision of the Party to break off personal relations with elements considered undesirable by the Party. This exclusion is not a reflection of the services of T.H. Wintringham in Spain, but he has shown himself unable to fulfil the obligations of a Party member.

(13) Tom Wintringham, New Ways of War (1940)

Knowing that science and the riches of the earth make possible an abundance of material things for all, and trusting our fellows and ourselves to achieve that abundance after we have won, we are willing to throw everything we now possess into the common lot, to win this fight. We will allow no personal considerations of rights, privileges, property, income, family or friendship to stand in our way. Whatever the future may hold we will continue our war for liberty.

(14) Tom Wintringham, letter (22nd May 1941)

Spain woke me up. Politically I rediscovered democracy, realising the enormous potentialities in a real alliance of workers and other classes, the power that can come from people working together for things felt and believed, when a popular front is not just a manoeuvre but a reality. I was disgusted by sectarian intrigues and by the hampering suspicions of Marry and co. I got self-confidence from K. and from the fact that some anonymous simple man always bobbed up to see me through tight places. Two bullets and typhoid gave me time to think. I came out of Spain believing, as I still believe, in a more humane humanism, in a more radical democracy, and in a revolution of some sort as necessary to give the ordinary people a chance to beat Fascism. Marxism makes sense to me, but the 'Party Line' doesn't.

(15) Time Magazine (30th June, 1941)

Last week doughty, democratic, battle-scarred Thomas H. Wintringham, 43, was allowed to resign from the leadership of Britain's Home Guard Training School, which he so largely created. Many an observer of Britain's war effort wondered whether the War Office - at times seemingly bow-&-arrow minded - was trying to lose the war.

Veteran of World War I and of the Spanish Civil War, in which he commanded the British battalion of the International Brigade, Tom Wintringham wrote and harangued against the spit-&-polish, close-order drill snobbery of Sandhurst. In a handbook called New Ways of War (TIME, Nov.11), he insisted that the only way to repel an invasion was to supplement Britain's regular forces with an army of 4,000,000 civilians trained with maximum democracy and efficiency. To this end the Home Guard Training School was organized, and Tom taught his men sniping, barricading, bombing with homemade bombs, garroting, how to decapitate an onrushing enemy motorcyclist with a piano wire, all the impromptu arts of guerrilla warfare.

Recently, just as Hugh Slater, the International Brigade's Chief of Staff, was about to be gazetted Home Guard major, the Army conscripted him as a private. The Army also grabbed Surrealist Painter Roland Penrose, Tom Wintringham's star camouflage lecturer.

Wrote Guerrillista Wintringham, probably well aware that his fellow-traveling had done him no good with the brass hats: "The present policy of the War Office starves the Home Guard of manpower and materials and treats as relatively unimportant all those ideas of modern-training tactics that I have been advocating." He quit.

(16) Tom Hopkinson, Of This Our Time (1982)

At Picture Post we had come to know Tom Wintringham, who had gained experience of German methods of warfare while fighting for the International Brigade in Spain. He was also an excellent writer with a clear style and a vigorous outlook, and in a series of articles during May and June had established himself as the mouthpiece of new ideas and methods of guerrilla warfare. Since these depended little on square-bashing or highly organized staff work - and much on adaptability, local knowledge and ability to live off the country - they made a strong appeal to the freebooting spirit of the day and to the general determination to 'get stuck into things' without waiting for someone in Whitehall to issue permits in triplicate.

One evening in the summer of 1940 Wintringham and I were having dinner with Edward Hulton at his house in Hill Street, and we talked of the frustration in the LDV- recently renamed the Home Guard - over the fact that all they were getting was practice in forming fours when they wanted to learn how to fight, and the question came up, 'Why don't we ourselves provide the training?'

Between dinner and midnight everything was organized. Hulton had a friend, the Earl of Jersey, who owned Osterley Park, a mansion with lavish grounds just outside London. Hulton phoned him, and he came round at once. Yes, of course, we could have his ground for a training course; he hoped we wouldn't blow the house up as it was one of the country's showplaces and had been in the family for some time.

(17) Tom Wintringham, The Picture Post (21st September, 1940)

As I was watching yesterday 250 men of the Home Guard take their places for a lecture at the Osterley Park Training School an air-raid siren sounded, and a dozen men with rifles moved to their prearranged positions as a defence unit against low-flying aircraft.

The lecturer began to talk of scouting, stalking and patrolling. And as I watched and listened I realized that I was taking part in something so new and strange as to be almost revolutionary - the growth of an "army of the people" in Britain - and, at the same time, something that is older than Britain, almost as old as England - a gathering of the "men of the counties able to bear arms."

The men at Osterley were being taught confidence and cunning, the use of shadow and of cover, by a man who learned field-craft from Baden-Powell, the most original irregular soldier in modern history (with the possible exception of Lawrence of Arabia). And in an hour or two they would be hearing of the experience, hard bought with lives and wounds, won by an army very like their own, the army that for year after year held up Fascism's flood-tide towards world power, in that Spanish fighting which was the prelude and the signal for the present struggle. I could not help thinking how like these two armies were: the Home Guard of Britain and the Militia of Republican Spain. Superficially alike in mixture of uniforms and half-uniforms, in shortage of weapons and ammunition, in hasty and incomplete organization and in lack of modem training, they seemed to me more fundamentally alike in their serious eagerness to learn, their resolve to meet and defeat all the difficulties in their way, their certainty that despite shortage of time and gear they could fight and fight effectively.

The school that they were attending had in a way been made by themselves. Two or three months ago, when this newest army in the world was first proposed, I wrote two articles in Picture Post on ways to meet invasion, on the experiences of Spain, and on the first rough steps to be taken for the training of a new force. So many queries piled into the offices of Picture Post, so many requests for more teaching and more detail, that it was natural for Mr. Edward Hulton to think of the idea of a school for the Home Guard - or, as they were then, the L.D.V. Osterley was a Picture Post idea, and Osterley has given free training to over 3,000 of the Home Guard at Edward Hulton's expense. The same evening that he decided to go ahead with the idea, he got in touch with Lord Jersey, who permitted us to use the grounds of his famous park at Osterley.

On July 10 the first course was given at the school. Our aim was then to give 60 members of the Home Guard two days' training three times a week. By the end of July over 100 men were attending each course, 300 a week. The numbers rose sharply in August; during the week when this was written one of the courses included 270 men.

Those attending the school in July were nearly a thousand; those attending in August over 2,000; the September figures will probably be around 3,000. We could not keep them away with bayonets - if we had any.

But all was not plain sailing; there were prejudices to be broken down. Soon after the school was founded an officer high up in the command of the L.D.V. requested Mr. Hulton and myself to close the school down, because the sort of training we were giving was "not needed." This officer explained to us with engaging frankness that the Home Guard did not have to do "any of this crawling round; all they have to do is to sit in a pill-box and shoot straight." The "sit in a pillbox" idea, a remnant of the Maginot Line folly not yet rooted out of the British Army, met us on other occasions.

(18) Tom Wintringham, New Ways of War (1940)

One thing admitted by all observers of the German attacks is that they use most of their bombers as a flying artillery. The second thing that enters into the German formula of warfare, all observers agree, is the use of heavy tanks, so powerfully armoured that they are not vulnerable to light anti-tank weapons.

The third main factor in the success of the German tactics and strategy is that they have employed and developed the tactics known as "deep infiltration." This means that their army does not attack strung but in a line, and maintaining contact all the time between its advanced units and its main forces. It does not hit like a fist, but like long probing fingers with armoured finger-nails. Each separate claw seeks a weak spot; if it can drive through this weak spot, it does not worry about its flanks, or about continuous communications with the forces following it. It relies for safety upon surprise, upon the disorganisation of its opponents due to the fact that it has broken through to the rear of their position.

(19) Tom Wintringham, New Ways of War (1940)

Blitzkrieg tactics and strategy are almost entirely developed with the idea of escaping from the trench deadlock that held the armies between August, 1914, and March, 1918, and held them again from September, 1939, to April, 1940. We can only grasp the essence of the Blitzkrieg if we realise that it is an opposite to, a reaction against, the war of trenches that otherwise condemns armies to practical uselessness.

From October, 1914, to March, 1917, on the Western Front, position warfare became more and more rigid, immovable, and futile. To "attack" meant to lose twice or three times as many men as your opponent, with no considerable gain in ground, and no decisive effect on anything except, your own cannon-fodder. The armies were locked in solid and continuous lines of trenches, in which they were pounded and obliterated by an even heavier hail of shells.

From March, 1917, to March, 1918, position warfare was in full flower, but some of the factors that must lead to its partial decay, its change into a new shape, became apparent. One factor was the tank; another, more important, was a new method of defence - which inevitably developed into its opposite, a new tactical method for infantry advance. The defensive method was known as "elastic defence" or "defence in depth"; the second developed from it, and adopted because it was a success, was called the tactic of "infiltration in attack."

(20) Tom Wintringham, New Ways of War (1940)

If we are to meet the new Nazi tactics, we must do the following:

1. Understand the tactics of infiltration and train our troops in them, and in methods of meeting them.

2. Realise the connection between these tactics and the trench deadlock; for defensive purposes realise that these tactics make linear defence and passive defence no longer valuable, and make counter-attack the only basis for successful defence.

3. Clear out of our army the remnants of the past - ideas, methods of training and organisation and the men who cannot change - and revive in the army the qualities necessary for carrying out and meeting infiltration: qualities of initiative, independence, the spirit of attack and counter- attack.

(21) Tom Wintringham, Freedom is Our Weapon (1941)

This war can be won. But it cannot be won by endurance only, by the power to " stick it", by remaining unchanged. We must change to win it, and we must change the war as well as ourselves. If this war is to be won it must cease to be one in which the conservative British Empire attempts to defend its possessions from German attack. It must become a war for the liberation of Europe and the world from Nazi and Fascist domination and aggression.

It will be argued in some circles that if the changes proposed here, and if privilege and profiteering were swept out of our lives, and a revolutionary democracy took over the army and other forces, finance and the factories, education and the land, shaping these things to the needs of the nation and not to the rights of owners - if these changes were tried, some say, the nation would be divided and our military force would thus be diminished. It is not true. It is true that some profiteers, if prevented from profiteering, might hope and work for a Nazi victory. But by profiteering they are already working for that victory, and working effectively even if they pretend to themselves that they are not traitors.

(22) Tom Wintringham, Freedom is Our Weapon (1941)

A conservative ruling class is incapable of fighting modern war effectively because war is changing very rapidly. And Conservatives do not admit change. They do not understand it. They cannot take advantage of it.

In our own last great war we won in the end, not by the brains of great generals or the "organising skill" of financiers, but by the employment of a strange new machine invented by journalists and engineers and pushed towards completion by a crank at the Admiralty. We won by the tank, more than by anything else.

The Germans admitted it. And the Germans learned from it, as they have shown more recently. We, on the other hand, do not seem to have learned quite so much.

Haig and other British generals, to whom each change in war was an unpleasant surprise, had been trained as great gentlemen are, not to notice unpleasant surprises, not to admit that they exist. He persisted with perfectly futile attacks, at enormous cost in lives, simply because he was too conservative to give up a method which clearly was failing, and attempt another. He had to be kicked and forced and harried into giving the tanks any chance of a large-scale battle suited to their new and strange technique. He avoided it for years on end. When at last he could avoid it no longer, it was the battle that more than any other won the war for us the attack of August 8, 1918.

This is only the first reason why the Conservative sections of our ruling class blundered in the last war, and in the present war so far have done worse than blunder. War changes and they do not; this is the first thing and the worst. There are others. War changes in a particular way, and one of the ways in which it has changed recently makes the initiative of very small groups of soldiers, their self-control and their power to lead themselves, a most valuable factor in battle.

(23) Tom Wintringham, Freedom is Our Weapon (1941)

Having seen much of the Home Guard, and knowing something of the defensive capacity of troops whose training has not been completed I believe that it ought to be possible by the summer of 1941 for the Home Guard and the training units to take over the major part of the work of defence in Britain, though they will always need a minimum of fully trained and fully -equipped regular divisions to assist them. By the summer of 1941 this minimum might be ten such divisions, and by September 1941 it might be cut down to seven, including one fully armoured division. But this will only be possible if the Home Guard is allowed to expand considerably. Recruiting for it is still severely restricted, and no effort has been made to run a recruiting campaign. The number of rifles available is necessarily limited ; but other weapons can be made available and it is no longer essential that every member of an infantry force should carry a rifle. The rifle has become a somewhat out-of- date weapon for many purposes; the other weapons can be made relatively quickly and cheaply.

I believe that a strengthening of the Home Guard in numbers, equipment and training is necessary, such as will enable the training of the rest of our army to be undertaken practically without reference to the defence of Britain. And since Britain, with its hedges and ditches, its many good roads and many built-up areas, is from a tactical point of view a peculiar and unusual country, the training of our Regulars should aim at adapting them to quite other countrysides.

(24) Tom Wintringham, Picture Post (20th December 1941)

We have an army that is very good. As Churchill has told us, it began this job with equality on the ground and superiority in the air. Can Mr. Churchill find leaders for it who will understand what Rommel was being taught from 1935? Can we find a staff worthy of the fighting men and commanders? That is the key question raised by the fighting in Libya, and what we know as yet of how that important battle has gone.

(25) Tom Wintringham, Politics of Victory (1941)

Marxism is a method of thought by which men understand the world and a method of action by which men change the world. Today for many millions of people war brings inexplicable disasters, and their need both to understand and change the world has never been so great. Yet among the many books about various aspects of this war there are very few that claim to be Marxist. This book does make that claim; it is an attempt to apply something that I believe to be an incomplete, growing science of human society to something that I know to be a complicated mess: the world of the Second World War.

Marxism starts from simple propositions such as this: that the way groups of men get their living determines the way these men live. And the way men live has a dominating influence on the way they think and feel. From the way men get their living, and think and feel and live, are derived their institutions and governments. These institutions and governments do not often change at the same pace as the changes that happen in the ways men get their living, and in men's thoughts and feelings. Men are divided into classes by the ways they get their living, and institutions and governments do not change easily and at once to reflect the changes in the strength of these classes (strength to understand the world and change it). Therefore sometimes it becomes necessary, if men are to go forward to new powers and towards new hopes, for institutions and governments to be broken and new ones built. These breakings and rebuildings are revolutions.

(26) Raymond Postgate, Tribune (9th August 1942)

Readers should know Tom Wintringham's work: if they do not, they have missed the foremost military expert in the world. I wonder if that phrase isn't a little gross? Never mind, let it stand. It is because he is the only socialist who has paid attention to the theory and practice of war. He is not a pundit: he does not work through the usual channels. His education of his fellow citizens has been carried out strictly democratically and by writings addressed to the public. Major-Generals have had to go out and buy Picture Post. Although the political deductions Tom has drawn made scarlet majors turn purple, the technical truth and importance of what he said is so great they had to read on, and in the end their blood pressure went down.

(27) Alan Wood, Tribune (25th August 1949)

I will never understand the news values of Fleet Street, the blank ignorance of newspaper editors on what sort of things the public are interested in. Here was a man who, during the war, was known to millions through the Picture Post and Daily Mirror and Penguin Books; as the prophet of the Home Guard his was an essential part in our finest hour. Could not one newspaper editor at least see an interest in the leader of that select band of Englishmen who had the honour of actively fighting for Spanish democracy? That is something for which he will always be remembered.

(28) Hugh Purcell, Tom Wintringham (2004)

At present Tom Wintringham is an historical footnote in several standard histories of Britain covering the first half of the last century. My aim is to elevate him to the main text as a unique English revolutionary, perhaps the last. His papers, now available for study in the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, show that his place in history is merited for four reasons:

1) He was the only significant Marxist military expert of his time. His books and pamphlets defined a Marxist way to revolution adapted to the reality of Britain and the world in the 1920s, 30s and 40s. In 1926 he was one of the Communist planners of the General Strike, the last time a revolution was feasible in Britain, for which he served a prison sentence for "sedition". (He had joined the C.P.G.B. in 1923, one of its few bourgeois recruits at that time, and remained in the Party until 1938). In the 1930s he argued in his books The Coming World War and Mutiny that an essential war against fascism should lead to a revolution in Britain because Britain was becoming a fascist state. He argued that in any modern war the anti-Fascists, that is the Communist-led skilled working class of civilians in munitions factories and soldiers and sailors in action, held revolutionary power in their hands. In the 1940s he turned his attention to guerrilla war against the occupying Nazis in Europe and Japanese in the Far East. He saw guerrilla war as a "people's war" for freedom and socialism and in the short term history proved him right.

2) He was one of the pioneers of the International Brigades that fought for the Republic in the Spanish Civil War between 1936-1938. Arguably, though it is not possible to prove, the actual idea for an "international legion" came from Wintringham. He was the first commander of the British Battalion in conflict, at the bloody Battle of Jarama in February 1937. Here in the first two days fighting the British lost 150 men, one third of their fatalities in the entire war. Wintringham was wounded at Jarama but survived this and also near fatal typhoid to return to the Battalion in the summer of 1937. Once again he was wounded and this time repatriated. His autobiographical account English Captain is considered one of the few classics of the war written in English. His war poetry too was published.