Lord Ashley, Earl of Shaftesbury

Anthony Ashley Cooper, the eldest son of the 6th Earl of Shaftesbury (1768–1851) and Lady Anne Spencer-Churchill (1773–1865), was born on 28th April, 1801. At the age of seven he was sent to boarding school and five years later he was transferred to Harrow (1813-16)At the age of ten, Anthony was given the courtesy title of Lord Ashley.

Harrow School (1813-16) was followed by Christ Church College, where he gained a first-class degree in classics. At the age of twenty-five he was elected as M.P. for Woodstock, a pocket borough under the control of his uncle, the Duke of Marlborough.

Lord Ashley's early political career was undistinguished and political reporters of the time complained that his speeches in the House of Commons were inaudible. He turned the offer of office from George Canning in April 1827, but early in 1828 he accepted from the Duke of Wellington a commissionership at the India Board of Control. According to his biographer, John Wolffe: "He sought to promote humanitarian and administrative reform in India, and also in 1828 took a leading part in securing legislation to protect lunatics. He was subsequently appointed to the metropolitan commission in lunacy."

In the general election of 1830 Ashley was returned for Dorchester. After the fall of the Wellington administration, he was offered the post under-secretaryship in the Foreign Office by the new prime-minister, Lord Palmerston. He refused and took a leading role in opposing the 1832 Reform Act.

Lord Ashley began to take an interest in social issues after reading reports in The Times about the accounts given before Michael Sadler and his parliamentary committee investigating child labour. He wrote: "I was astonished and disgusted by what I read. I wrote to Sadler offering my services. In February the Rev. George Bull asked me to take up the question that Sadler had been forced to drop. I can perfectly recollect my astonishment, and doubt, and terror, at the proposition."

When Michael Sadler was defeated in the 1832 General Election, Lord Ashley was approached by John Wood and the Rev. George Bull, the Evangelical curate of Bierly near Bradford, to become the new leader of the factory reform movement in the House of Commons. Ashley's critics claimed that he took up the factory question "as much from a dislike of the millowners as from sympathy with the mill-workers."

Lord Ashley agreed to George Bull's request and in March 1833, he proposed a bill that would restrict children to a maximum ten hour day. On 18th July, 1833, Ashley's bill was defeated in the House of Commons by 238 votes to 93. Although the government opposed Ashley's bill it accepted that children did need protecting and decided to put forward its own proposals. The government's 1833 Factory Act was passed by Parliament on 29th August.

Under the terms of the new act, it became illegal for children under nine to work in textile factories, whereas children aged between nine and thirteen could not be employed for more than eight hours a day. The main disappointment of the reformers was that children over thirteen were allowed to work for up to twelve hours a day. They also complained that with the employment of only four inspectors to monitor this legislation, factory owners would continue to employ very young children.

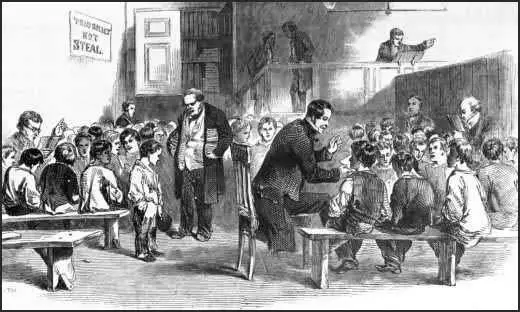

Other social issues that interested the Earl of Shaftesbury included the provision of working class education and was chairman of the Ragged Schools Union for over forty years. John Wolffe has argued: "Ashley's growing sense of himself as a lone crusader was undergirded in the course of the 1830s by a deepening of his religious commitment. He had always been a sincere and pious Christian, but his beliefs now assumed an unambiguously evangelical character, sustained in particular by his friendship from 1835 with the leading divine Edward Bickersteth. Ashley became convinced of the imminence of the premillennial second advent of Christ, an expectation which for him engendered a sense not of fatalism, but rather of the urgency of saving souls and of reforming national life so as to mitigate the impact of the coming divine judgment. This conviction remained fundamental to the intensity and passion with which he pursued his numerous concerns."

On 4th August, 1840, Lord Ashley said in the House of Commons: "The future hopes of a country must, under God, be laid in the character and condition of its children; however right it may be to attempt, it is almost fruitless to expect, the reformation of its adults; as the sapling has been bent, so will it grow. The first step towards a cure is factory legislation. My grand object is to bring these children within the reach of education."

Later that year Lord Ashley helped set up the Children's Employment Commission. Its first report on mines and collieries was published in 1842. The report caused a sensation when it was published. The majority of people in Britain were unaware that women and children were employed as miners. Later that year Lord Ashley piloted the Coal Mines Act through the House of Commons. As a result of this legislation all females and boys under ten years old from working underground in coal mines. However, only one inspector was appointed for the entire country and so colliery owners continued to employ women and children in mines.

Lord Ashley also continued to lead the campaign for a reduction in the hours that children worked in factories. In 1841 Ashley received a manuscript from William Dodd about his experiences as a child worker. Lord Ashley, arranged for it to be published as A Narrative of the Experience and Sufferings of William Dodd a Factory Cripple. Lord Ashley decided to employ Dodd to collect information about the treatment of children in textile factories. William Dodd's research was published as The Factory System: Illustrated in 1842.

William Dodd's books created a great deal of controversy. William Dodd was attacked in the House of Commons as an unreliable source of information. John Bright: "I have in my hand two publications; one is The Adventures of William Dodd he Factory Cripple and the other is entitled The Factory System - both books have gone forth to the public under the sanction of the noble Lord Ashley. I do not wish to go into the particulars of the character of this man, for it is not necessary to my case, but I can demonstrate, that his books and statements are wholly unworthy of credit. Dodd states that from the hardships he endured in a factory, he was "done up" at the age of thirty-two, whereas I can prove that he was treated with uniform kindness, which he repaid by gross immorality of conduct, and for which he was discharged from his employment." As a result of this attack Lord Ashley decided to sack Dodd.

In 1851 Anthony Ashley Cooper's father died and he now became the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. He continued to campaign for effective factory legislation. In 1863 he published a report that revealed that children as young as four and five were still working from six in the morning to ten at night in some British factories.

Cooper told his friend Edwin Hodder: "My religious views are not very popular but they are the views that have sustained and comforted me all though my life. I think a man's religion, if it is worth anything, should enter into every sphere of life, and rule his conduct in every relation. I have always been - and, please God, always shall be, an Evangelical."

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, died on 1st October, 1885.

Primary Sources

(1) Lord Ashley personal memorandum, February, 1833

In the autumn and winter of 1832 I read in The Times some extracts from the evidence taken before Sadler's Committee. I was astonished and disgusted by what I read. I wrote to Sadler offering my services. In February the Rev. George Bull asked me to take up the question that Sadler had been forced to drop. I can perfectly recollect my astonishment, and doubt, and terror, at the proposition.

(2) Lord Ashley, speech in the House of Commons, 9th May, 1836

Of the thirty-one medical men who were examined, sixteen gave it as their most decided opinion that ten hours is the utmost quantity of labour which can be endured by the children, with the slightest chance of preserving their health. Dr. Loudon reports, "I am of the opinion no child under fourteen years of age should work in a factory of any description more than eight hours a day." Dr. Hawkins reports, "I am compelled to declare my deliberate opinion, that no child should be employed in factory labour below the age of ten; that no individual, under the age of eighteen, should be engaged in it longer than ten hours daily."

(3) Lord Ashley, speech in the House of Commons (4th August, 1840)

The future hopes of a country must, under God, be laid in the character and condition of its children; however right it may be to attempt, it is almost fruitless to expect, the reformation of its adults; as the sapling has been bent, so will it grow. The first step towards a cure is factory legislation. My grand object is to bring these children within the reach of education.

(4) William Dodd, A Narrative of William Dodd,: A Factory Cripple (1841)

The fat of horses, dogs, pigs, and many other animals, which die a natural death, or are killed with some incurable disease upon them, is sold to the manufacturers, and kept for the purpose of greasing the heavy machinery. It may be imagined what sort of smell will arise from the application of this fat to shafts almost on fire.

(5) John Bright, speech in the House of Commons (15th March, 1844)

I have in my hand two publications; one is The Adventures of William Dodd he Factory Cripple and the other is entitled The Factory System - both books have gone forth to the public under the sanction of the noble Lord Ashley. I do not wish to go into the particulars of the character of this man, for it is not necessary to my case, but I can demonstrate, that his books and statements are wholly unworthy of credit. Dodd states that from the hardships he endured in a factory, he was "done up" at the age of thirty-two, whereas I can prove that he was treated with uniform kindness, which he repaid by gross immorality of conduct, and for which he was discharged from his employment.

(6) Lord Ashley told his friend, Edwin Hodder, why he had spent much of his life involved in social reform.

My religious views are not very popular but they are the views that have sustained and comforted me all though my life. I think a man's religion, if it is worth anything, should enter into every sphere of life, and rule his conduct in every relation. I have always been - and, please God, always shall be, an Evangelical.