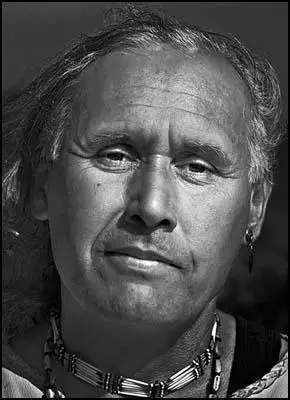

Chumash

The Chumash lived along the Pacific Coast from San Luis Obispo to Malibu in the south and inland to the San Joaquin Valley. According to Evelyn Wolfson: "It is an area of long mountain ranges, broad valleys, freshwater rivers, and dry plains. Food resources were limitless and the Indians lived entirely off the land all year. On the hilly rugged offshore islands, strong winds and constant mild temperatures provided excellent fishing."

According to the authors of The Natural World of the California Indians (1980): "The Chumash were the most sea-oriented people of the state, a specialization made possible by their seagoing plank canoes, which were propelled by double-bladed paddles. The Chumash had colonized the offshore islands of Santa Barbara, San Miguel, Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa".

Jean-François de Galaup was one of the first to record the behaviour of these tribes on the coast of California: "These Indians are extremely skillful with the bow and killed before us the smallest birds. Their patience in approaching them is inexpressible. They conceal themselves and slide in a manner after their game, seldom shooting until within fifteen paces. Their industry in hunting larger animals is still more admirable. We saw an Indian with a stag's head fastened on his own, walking on all fours and pretending to graze. He played this pantomime with such fidelity, that our hunters, when within thirty paces, would have fired at him if they had not been forewarned. In this manner they approach a herd of deer within a short distance, and kill them with their arrows."

In 1542 Antonio de Mendoza, the new viceroy of New Spain, commissioned the experienced navigator, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, to lead an expedition up the California coast in search of trade opportunities and to find the Strait of Anián, purportedly linking the Pacific and the Atlantic. On 27th June, Cabrillo sailed from the port of La Navidad along the Mexican coast north of Acapulco, rounded the tip of the Baja Peninsula and then moved slowly north. On 28th September, Cabrillo anchored in San Diego Bay. Cabrillo and his men therefore became the first Europeans to reach California from the sea. Soon after landing Cabrillo encountered members of the Chumash tribe.

In 1765 King Carlos III of Spain sent José de Gálvez to New Spain with orders to organize the settlement of Alta California. Inspector General Gálvez recruited Gaspar de Portolà and Junipero Serra in what became known as the "Sacred Expedition". It was decided that three ships, the San Carlos, the San Antonio, and the San José, should sail to San Diego Bay. It was also agreed to send two parties to make an overland journey from the Baja to Alta California.

The first ship, the San Carlos, sailed from La Paz on 10th January, 1769. The other two ships left on 15th February. The first overland party, led by Fernando Rivera Moncada, left from the Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá on 24th March. With him was Father Juan Crespi, who had been given the task of recording details of the trip. The expedition led by Portolà, which included Father Serra, set off on 15th May.

Moncada reached San Diego in May. He built a camp and waited for the others to arrive. The San Antonio, reached its destination in fifty-four days. The San Carlos took twice that time and the San José was lost with all aboard. The second overland party arrived on 1st July. Out of a total of two hundred and nineteen men who left Baja California, just over a hundred survived the journey. Some of these were to die while the San Antonio sailed back to La Paz for supplies and reinforcements.

In 1772 Father Junipero Serra established Mission San Luis Obispo. He soon came into contact with the Chumash people. According to Tracy Salcedo-Chouree, the author of California's Missions and Presidios (2005): "The valley was home to Chumash Natives, an amiable and intelligent people with whom the Spaniards shared the spoils of their bear hunt and who later would be recruited as neophytes of the mission." The Spanish were impressed by Chumash stonework and basketry. Alfred L. Kroeber thought that in the 1770s the population of the Chumash might have been about 10,000. Evelyn Wolfson argues: "The Spanish forced the Chumash to work for them. Many died from disease, overwork, and a lack of nourishing food."

The Chumash employed shamans to cure illness, to bring rain, and to insure an abundant supply of food. They believed that shamans were intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat illness by mending the soul. Shamans also preserve traditions by storytelling and singing songs.

In 1824 the Chumash rebelled against the Spanish but the revolt failed and they were forced to live in the mountains. When they were captured they became slaves of the Mexican ranchers. After the Mexican War American settlers also forced the Chumash to work on their farms and ranches. Descendants of the Chumash live on the Zanja de Cota Reservation in California.