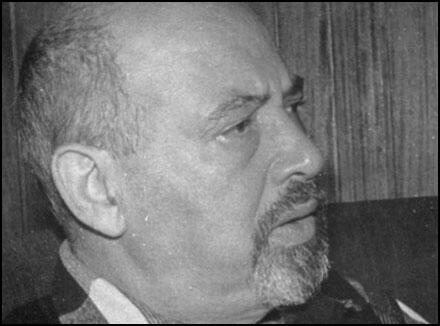

Max Shachtman

Max Shachtman was born in Warsaw, Poland, on 10th September 1904. His family emigrated with his family to New York City when he was a small child.

Shackman was very interested in politics and as a teenager joined the Socialist Party of America. The right-wing leadership of the party opposed the Russian Revolution. However, those members who disagreed with this policy formed the Communist Propaganda League.

In February 1919, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe, Louis Fraina, John Reed and Benjamin Gitlow created a left-wing faction that advocated the policies of the Bolsheviks in Russia. On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members who supported this faction. The process continued and by the beginning of July two-thirds of the party had been suspended or expelled.

American Communist Party

In September 1919, Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the Communist Party of the United States. Within a few weeks it had 60,000 members whereas the Socialist Party of America had only 40,000.

Initially, the American Communist Party was divided into two factions. One group that included Charles Ruthenberg, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe and Benjamin Gitlow, favoured a strategy of class warfare. Another group, led by William Z. Foster, William Dunne and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor. Shackman associated with the group led by Foster.

Shackman contributed to the party journal, The Young Worker. As the editor of The Labor Defender he joined with others such as William Z. Foster, Edna St Vincent Millay, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Floyd Dell in the campaign against the proposed execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.

Leon Trotsky

James Cannon, the first chairman of the American Communist Party, attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928. While in the Soviet Union he was given a document written by Leon Trotsky on the rule of Joseph Stalin. Convinced by what he read, when he returned to the United States he criticized the Soviet government. As a result of his actions, Cannon and his followers, including Shactman, were expelled from the party.

Shachtman, James Cannon and Martin Abern now joined with other Trotskyists to form the Communist League of America (CLA). The party also published the journal, The Militant. In July 1933, Shactman moved to France to live with Leon Trotsky and over the next few months worked as his secretary. In 1934 Shackman joined forces with Farrell Dobbs to publish The Organizer, a newspaper created to support the Minneapolis Teamster Strike.

Workers Party of the United States

In 1934 the party merged with the American Workers Party, to form the Workers Party of the United States, under the joint leadership of Abraham Muste and James Cannon. The party was dissolved in 1936 when it was decided that members should join the successful Socialist Party of America. During this period Shackman edited the New International, wrote a book on the Great Purge entitled, Behind the Moscow Trial (1936) and translated Leon Trotsky's The Stalin School of Falsification (1937).

Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, decided to expel the Trotskyists in 1937. Shachtman and James Cannon now decided to form the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). In March 1938, Shachtman and Cannon were part of a delegation sent to Mexico City to discuss the draft Transitional Program of the Fourth International with Leon Trotsky.

Shachtman became disillusioned with the Soviet Union when it signed the Soviet-Nazi Pact. These feelings were intensified when the Red Army invaded Poland (September, 1939) and Finland (November 1939). James Cannon continued to support the foreign policy of Joseph Stalin. Cannon, like Leon Trotsky, believed that the Soviet Union was "degenerated workers' state", whereas Shachtman argued that Stalin was developing an imperialist policy in Eastern Europe. Shachtman decided to leave the Socialist Workers Party and establish his own Workers Party. Other members included Martin Abern, C.L.R. James, Hal Draper, Joseph Carter, Julius Jacobson and Irving Howe.

Max Shachtman continued as editor of New International during the Second World War and in 1943 he predicted that the Red Army would impose Stalinism in Eastern Europe. In 1949 the Workers Party became the Independent Socialist League (ISL).

The Bureaucratic Revolution

In 1962, Shachtman published The Bureaucratic Revolution: The Rise of the Stalinist States. In the book he argued that capitalism and Stalinism to be equal impediments to socialism. In 1958, the ISL dissolved so that its members could join the Socialist Party of America. Shachtman also believed that socialists should try to move the Democratic Party to the left from within. Shachtman also worked closely with Bayard Rustin and the Civil Rights Movement.

Shachtman's anti-communism moved him to the right and upset fellow members by refusing to condemn the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and his unwillingness to call for US armed forces to leave Vietnam. This alienated former supporters such as Walter Reuther and Michael Harrington. When George McGovern became the Democratic Party candidate in 1972 on an anti-war manifesto, Shachtman refused to endorse him.

Max Shachtman died on 4th November 1972.

Primary Sources

(1) The Militant (17th December 1928)

The Political Committee of the Workers (Communist) Party expelled Cannon, a member of that committee, along with Martin Abern and Max Shachtman, member and alternate respectively of the party's Central Executive Committee, on charges of Trotskyism on October 27, 1928. But they had the right of appeal to the approaching plenary session of the Central Executive Committee. The following is the speech delivered to that plenum on December 17, 1928.

Comrades:

Many of the most important events and turning points in our party's life have been summed up in party gatherings, which stand out in party history as the expression of these events. The present meeting of the Central Executive Committee, called to confirm the control of the party by an opportunistic and bureaucratic leadership and to endorse the expulsion of its opponents, is such a gathering. It will represent in party history a downward Curve...

In the period that has intervened since our expulsion on October 25, we have continued to regard ourselves as party members and have conducted ourselves as Communists, as we have done since the foundation of the party, and even for years before that. Every step we have taken has been guided by this conception. Those acts which went beyond the bounds of ordinary party procedure in bringing our views before the party were imposed upon us by the action of the party leadership in denying us the right and opportunity to defend our views within the party by normal means. Our views relate to principled questions, and therefore it is our duty openly to defend them in spite of all attempts to suppress them.

We are bound to do this also in the future under all circumstances. However, we said on October 25, and we repeat now, that we are unconditionally willing to confine our activity to regular party channels and to discontinue all extraordinary methods the moment our party rights are restored and we are permitted to defend our views in the party press and at party meetings. The decision and the responsibility rest wholly with the majority of the Central Executive Committee.

Events since our expulsion have only served to confirm more surely the correctness of the views of the Russian Opposition, which we support. The momentous developments in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and throughout the Comintern have that meaning and no other. Life itself is proving the validity of their platform. Even those who fought that platform, who misrepresented it and hid it from the party and the Comintern, are today compelled, under the pressure of events and forces which overwhelm them, to give lip service to it, to pretend to adopt it. Many of the statements and proposals of the Opposition which were branded "counterrevolutionary" a year ago are today solemnly repeated, almost word for word, as the quintessence of Bolshevism.

Meanwhile their sponsors - the true leaders and defenders of the Russian Revolution - remain in exile, and there is no guarantee whatever that the presently advertised "left course" will mean anything more than a cover for further concessions to the right wing, whose policy directly undermines the dictatorship. The victorious fight of the party masses in Russia and throughout the Comintern against this disgraceful and dangerous course cannot be much longer postponed...

Our views on the problems of the American party and its leadership, outlined in our statement to the Political Committee on October 25, hold good today and have been underscored by the whole conduct of the Pepper-Lovestone faction since that time. We spoke then of "its opportunist political outlook, its petty-bourgeois origin, its corrupt factionalism, its careerism and adventurism in the class struggle" as "the greatest menace to the party." To speak now about the present party leadership with objectivity and precision, we could not use different language to characterize it This estimate is written in unmistakable words in the election campaign, the trade-union work, the inner-party regime and in all phases of party life and activity.

Since October 25, the Pepper-Lovestone leadership has taken further steps on the course of bureaucratic disruption which confronts the party today as a deadly menace - a course which began with the expulsion of Communists, copied from the labor fakers, and which has already taken another weapon from the same arsenal: the weapon of gangsterism. Everyone sitting here knows the facts about this. You know that inspired and organized gangster attacks have been made against us on the public streets, not once but several times.

Woe to the party of the workers if its proletarian kernel does not arise and stamp out these incipient fascist tactics at the very beginning! The blows from the black jacks of gangsters which have descended on the heads of Opposition Communists are blows at the very foundation of the party. This abominable gangsterism, for which the leaders of the two factions collaborating against us, the Lovestone faction and the Foster faction, are directly responsible, is hated by every honest worker. It dis credits the party before the working class and threatens to deprive the party of its moral and political position in the struggle against these methods of the trade-union reactionaries.

(2) Max Shachtman, Socialist Appeal (October 1936)

Unless we are the "gullible idiots" who Trotsky says would have to people the world if the charges made against the sixteen men just tried and shot in Moscow, were to be believed, we must conclude that the very indictment and execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev and the fourteen others constitute in actuality the most crushing indictment yet made of the Stalin regime itself. The real accused in the trial were not on the defendants' bench before the Military Tribunal. They were and they remain the usurping masters of the Kremlin - concocters of a hideous frame-up.

The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?

Leon Trotsky, organizer and leader, together with Lenin, of the October Revolution, and founder of the Comintern.

Zinoviev: 35 years of his life in the Bolshevik party; Lenin's closest collaborator in exile and nominated by him as first chairman of the Communist International; chairman of the Petrograd Soviet for years; member of the Central Committee and the Political Bureau of the C.P. for years.

Kamenev: also 35 years spent in the Bolshevik party; chairman of the Political Bureau in Lenin's absence; chairman of the Moscow Soviet; chairman of the Council of Labor and Defense; Lenin's literary executor.

Smirnov: head of the famous Fifth Army during the civil war; called the "Lenin of Siberia;" a member of the Bolshevik party for decades.

Yevdokimov: official party orator at Lenin's funeral; leader of the Leningrad party organization for many years; member of the Central Committee at the time Kirov died.

Ter-Vaganian: theoretical leader of the Armenian communists; founder and first editor of the party's review, "Under the Banner of Marxism."

Mrachkovsky: defender of Ekaterinoslav from the interventionist Czechs and the White troop during the civil war.

Bakayev: old Bolshevik leader in Moscow; member of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission during Lenin's time.

Sokolnikov: Soviet ambassador to England; creator of the "chervonetz," the first stable Soviet currency.

Tomsky: head of the Russian trade union center for years; old worker-Bolshevik; member of the Central Committee and Political Bureau for years.

Rykov: old Bolshevik leader; Lenin's successor as chairman of the Council of People's Commissars.

Serebriakov: Stalin's predecessor in the post of secretary of the C.P.

Bukharin: for years one of the most prominent theoreticians of the Bolsheviks; chairman of the Comintern after Zinoviev; editor of official government organ, Isvestia.

Kotsubinsky: one of the main founders of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic.

General Schmidt; head of one of the first Red Cavalry brigades in the Ukraine and one of the country's liberators from the White forces.

Other heroes of the Civil War, like General Putna, military attache till yesterday of the Soviet Embassy in London; Gertik and Gaevsky; Shaposhnikov, director of the Academy of the General Staff; Klian Kliavin.

Heads of banking institutions; chiefs of industrial trusts; heads of educational and scientific institutions; party secretaries from one end of the land to the other; authors (Selivanovsky, Serebriakova, Katayev, Friedland, Tarassov-Rodiondv); editors of party papers; high government officials (Prof. Joseph Lieberberg, chairman of the Executive Committee of the Jewish Autonomous Republic of Biro-Bijan); etc., etc.

Now to charge, as has been done, all these men and women, plus hundreds and perhaps thousands of others, with having engaged to one extent or another, in an assassination plot, is equivalent, at the very outset and on the face of the matter, to an involuntary admission by the accusing bureaucracy.

1. That its much-vaunted popularity and the universality of its support among the population, is fantastically exaggerated.

2. That it has created such a regime in the party and the country as a whole, that the very creators of the Bolshevik party and revolution, its most notable and valiant defenders in the crucial and decisive early years, could find no normal way of expressing their dissatisfaction or opposition to the ruling bureaucracy and found that the only way of fighting the latter was the way chosen, for example, by the Nihilists in their struggle against Czarist despotism, namely, conspiracy and individual terrorism.

3. That the "classless socialist society irrevocably" established by Stalin is so inferior to Fascist barbarism on the political, economic and cultural fields, that hundreds of men whose whole lives were prominently devoted to the cause of the proletariat and its emancipation, decided to discard everything achieved by 19 years of the Russian Revolution in favor of a Nazi regime.

4. And, not least of all, that the Russian Revolution was organized and led by an unscrupulous and perfidious hand of swindlers, liars, scoundrels, mad dogs and assassins. Or, more correctly, if these were not their characteristic in 1917 and the years immediately thereafter, then there was something about the gifted and beloved leadership of Stalinism that reduced erstwhile revolutionists and men of probity and integrity to the level of swindlers, liars, scoundrels, mad dogs and assassins.

These are the outstanding counts in the self-indictment of the bureaucracy. To them must be added the charge of a clumsy and cynical frame-up. Even a casual examination of the very carefully edited record of the trial that has thus far been made public, so thoroughly reveals its trumped-up, staged nature, as to deprive all the avidly made "confessions" of so much as an ounce of validity.

(3) Max Shachtman, speech at New York City's Webster Hall on 30th March, 1950.

If the cold horror of Stalinist despotism, that vast prison camp of peoples and nations, represents the victory of socialism, then we are lost; then the ideal of socialist freedom, justice, equality, and brotherhood has proved to be an unattainable Utopia; then the National Association of Manufacturers is right in saying that while capitalism is not perfect and has a couple of defects here and there, socialism is a new slavery; then we must be resigned to that appalling decay of modern civilization that is eating away the substance of human achievement. But if it can be shown that Stalinist Russia is not socialism, that it has nothing in common with socialism, that it is only another and very ominous lesson of what happens to society when the working class fails to fight, and extend its fight, for socialism, or when its fight is arrested or crushed; if it can be shown that Stalinist Russia is a new barbarism which results precisely from our failure up to now to establish a socialist society, to extend the Revolution of 1917 that took place in Russia - then, despite the agony that grips the world today, there is a hope and a future for the socialist emancipation of the race. It is from that standpoint and no other that I will seek to show that Stalinist Russia has nothing at all in common with socialism. The best way to begin is by defining socialism.

Socialism is based upon the common ownership and democratic control of the means of production and exchange, upon production for use as against production for profit, upon the abolition of all classes, all class divisions, class privilege, class rule, upon the production of such abundance that the struggle for material needs is completely eliminated, so that humanity, at last freed from economic exploitation, from oppression, from any form of coercion by a state machine, can devote itself to its fullest intellectual and cultural development. Much can perhaps be added to this definition, but anything less you can call whatever you wish, but it will not be socialism.

Now, if this definition is correct - as it has been considered by every socialist from the days of Marx to the days of Lenin - then there is not only not a trace of socialism in Russia, but it is moving in a direction which is the very opposite of socialism.

It is absolutely true that by their revolution in 1917 the Russian working class, under the leadership of the Bolsheviks, took the first great, bold, inspiring leap toward a socialist society. And that alone, regardless of what happened subsequently, justified it and made it a historic event that can never be eliminated from the consciousness of society. But it is likewise true that the working class of Russia was hurled back, it was crushed, and fettered and imprisoned, and that every achievement of the revolution, without exception, was destroyed by the victorious counter-revolution of the Stalinist bureaucracy which now rules the Russian empire with totalitarian absolutism.