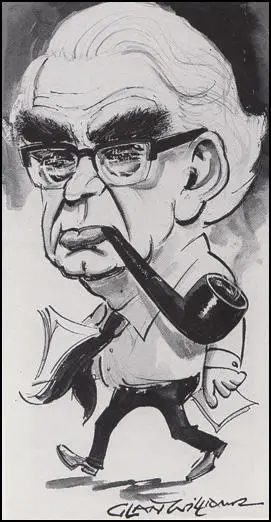

Ian Mikardo

Ian Mikardo, the son of Moshe (Morris) Mikardo, a tailor, and his wife, Bluma, was born on 9th July 1908. Both his parents came to Britain in the massive exodus from Russia during the Jewish Pogroms that were blamed on Tsar Nicholas II in 1903. (1)

Mikardo later recalled that when his father "disembarked at London Dock his total possessions were the clothes he stood up in, plus a little bag containing a change of shirt and underclothes and his accessories for prayer - a talis (prayer-shawl) and a sidur (prayer book) and tefilin (phylacteries) - plus one rouble... He didn't know a word of English, or indeed of any language other than Yiddish... He couldn't read or write a word of even his own language, nor sign his name." (2)

When he entered his first school in Portsmouth he had only a few words of English, which put him at a disadvantage with his classmates. His mother wanted him to become a rabbi and was sent to Aria College but he eventually rejected the idea and went to a local secondary school. He left school at fifteen and did a variety of different jobs. He took a keen interest in politics and after being converted to socialism by the writings of Richard Tawney and George Bernard Shaw he joined the Labour Party. (3)

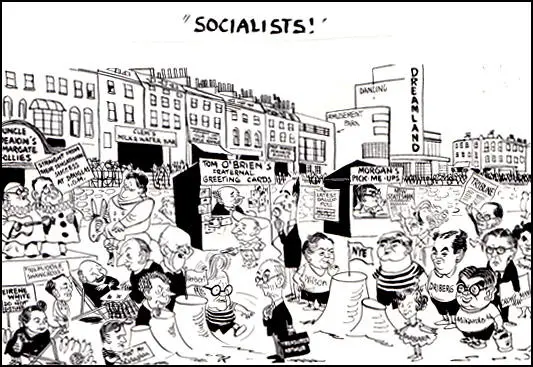

Ian Mikardo - Socialist

In 1930 Mikardo met Mary Rosetsky. They married two years later. He became involved in the struggle against the Ramsay MacDonald government. In August 1931, Philip Snowden wanted to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes.

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn and Margaret Bondfield lost their seats.

Mikardo lost interest in politics as a result of this defeat. Like many others during the Great Depression "the mundane grind of earning a living left little time or energy or resources for anything else." (4) He worked in several factories and warehouses, before becoming a management consultant. "I got a junior job in a small consultancy organisation specializing in revamping distribution and sales departments, and then went on to a slightly better job in a somewhat bigger group, but I wasn't satisfied with them because I felt their investigations were a bit superficial, and I began to think about starting up on my own account so that I could put to use all the ideas on organisation and management which had crystallized in my mind and were screaming out to be tested in practice." (5)

During the Second World War he worked as an administrator in the aircraft-building industry. In 1944 Mikardo published Centralised Control of Industry, advocating the extension into peacetime of wartime controls on industry. That year he was adopted as the Labour candidate for Reading, regarded at the time as a safe Conservative seat. "He quickly introduced a more ‘scientific’ approach to canvassing, dividing the electorate into ‘fors’, ‘againsts’, and ‘don't knows’, and concentrating his activists' efforts on persuading the fors to vote and converting the ‘don't knows’; the ‘Reading system’, as it came to be called, was subsequently adopted by all the major parties." (6)

1945 General Election

At the Labour National Conference in December 1944, Ian Mikardo proposed a resolution that was strongly opposed by the leadership of the Labour Party. It restated the fundamental socialist principles of the party. In his speech he called for the nationalisation of "the land, large-scale building, heavy industry and all forms of banking" as well as transport, fuel and power. (7)

During the debate Harold Laski asked Mikardo to withdraw the resolution for the sake of party unity. Mikardo refused and the "resolution was carried on a show of hands by such a large majority that no-one dared to call for a card vote." Herbert Morrison, the leader of the right-wing section of the party, said to Mikardo: "Young man, you did very well this morning. That was a good speech you made - but you realise, don't you, that you've lost us the general election." (8)

It was unclear during the 1945 General Election who would win. On 4th June, 1945, Winston Churchill made a radio broadcast where he attacked Clement Attlee and the Labour Party: "I must tell you that a socialist policy is abhorrent to British ideas on freedom. There is to be one State, to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State, once in power, will prescribe for everyone: where they are to work, what they are to work at, where they may go and what they may say, what views they are to hold, where their wives are to queue up for the State ration, and what education their children are to receive. A socialist state could not afford to suffer opposition - no socialist system can be established without a political police. They (the Labour government) would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo." (9)

Ian Mikardo believes that the Churchill broadcast helped his election campaign: "In his first election broadcast on the radio he warned the country that if they elected a Labour government they would find themselves under the jackboots of a socialist gestapo. The British people just wouldn't take that. They looked at Clem Attlee, the timid, correct, undemonstrative, unaggressive ex-public-schoolboy, ex-major, and couldn't see an Adolf Hitler in him." (10)

Attlee's response the following day caused Churchill serious damage: "The Prime Minister made much play last night with the rights of the individual and the dangers of people being ordered about by officials. I entirely agree that people should have the greatest freedom compatible with the freedom of others. There was a time when employers were free to work little children for sixteen hours a day. I remember when employers were free to employ sweated women workers on finishing trousers at a penny halfpenny a pair. There was a time when people were free to neglect sanitation so that thousands died of preventable diseases. For years every attempt to remedy these crying evils was blocked by the same plea of freedom for the individual. It was in fact freedom for the rich and slavery for the poor. Make no mistake, it has only been through the power of the State, given to it by Parliament, that the general public has been protected against the greed of ruthless profit-makers and property owners. The Conservative Party remains as always a class Party. In twenty-three years in the House of Commons, I cannot recall more than half a dozen from the ranks of the wage earners. It represents today, as in the past, the forces of property and privilege. The Labour Party is, in fact, the one Party which most nearly reflects in its representation and composition all the main streams which flow into the great river of our national life." (11)

Keep Left Group

Ian Mikardo won the seat at Reading: "We began the count at nine in the morning (26 July, 1945), and by midday I had been announced the winner with a majority of 6,390 over the Conservative candidate... I led a small army of wildly enthusiastic supporters across the market place and into the Labour Club for some celebratory drinks, though truth to tell we were all already hilariously drunk with unexpected triumph." (12)

Clement Attlee, the new prime minister, refused to appoint either Mikardo or Austen Albu, to positions in the government, apparently on racial grounds. "They both belonged to the Chosen People, and he did not think that he wanted any more of them!" (13)

Attlee was also not enthusiastic about the nationalisation programme proposed by Mikardo at the 1944 Labour Conference. However, it now had the support of the vast majority of its membership and he agreed to put it into operation. As Hugh Dalton pointed out: "We weren't really beginning our Socialist programme until we had gone past all the utility junk - such as transport and electricity - which were publicly owned in every capitalist country in the world. Practical Socialism... really began with Coal and Iron and Steel, and there was a strong political argument for breaking the power of a most dangerous body of capitalists." (14)

Mikardo was popular with his constituents: "At first we were not unduly impressed. No overwhelming charm of manner or appearance, a harsh, somewhat adenoidal voice, and yet, within minutes he had won our respect and, soon after, even a grudging affection. Whatever the topic - the National Health Service, education, social deprivation, nationalisation or socialism itself - he inspired others. He knew where he was going and we wanted to go with him … above all Ian Mikardo had that rarest of qualities among professional politicians - integrity." (15)

Mikardo was on the left of the party. In 1947 he joined Richard Crossman, Michael Foot, Konni Zilliacus, John Platts-Mills, Lester Hutchinson, Leslie Solley, Sydney Silverman, Geoffrey Bing, Emrys Hughes, D. N. Pritt, George Wigg, John Freeman, Richard Acland, William Warbey, William Gallacher and Phil Piratin in forming the Keep Left Group. They urged Clement Attlee to develop left-wing policies and were opponents of the cold war policies of the United States and urged a closer relationship with Europe in order to create a "Third Force" in politics. (16)

In 1947 Mikardo, Crossman and Foot published Keep Left. The pamphlet argued for a system of state planning: "Such a planning mechanism, to be successful, needs to be able not merely to co-ordinate the work of the departments of State but also to reconcile conflicts of view between them, and even to override them when the need arises. For this purpose, it must be headed by a Minister who can give the necessary time to the job, and who has a position and prestige above those of the departmental Ministers. We haven't got that yet." (17)

Mikardo later recalled: "In Keep Left the greater part of our discussions was about the basic philosophy of the Party and the sort of broad economic and social order we should be seeking to create. Between 1947 and 1950 we concentrated on the production of a wide-ranging programme for the next Labour government: we worked hard at it, writing and circulating papers, some of them long and detailed, on different policy areas, and discussing and amending them." (18)

Richardson helped Mikardo write The Second Five Years (1948). In a pamphlet they argued that the government needed to "nationalise the joint stock banks and industrial assurance companies, shipbuilding, aircraft construction, areo-engines, machine tools, and the assembly branch of mass-produced motor vehicles". This was followed by Keeping Left (1950) in which the Keep Left Group advocated the "public ownership of road haulage, steel, insurance, cement, sugar and cotton." (19)

These ideas were rejected by the Labour leadership of "electoral grounds". In the 1950 General Election manifesto, the only candidates for public ownership were "sugar, cement, meat wholesaling and water supplies - a curiously peripheral ragbag which scarcely threatened the commanding heights of the economy". (20) The manifesto failed to motivate voters and they ended up losing 78 seats but still retained control of the House of Commons. (21)

attacking Herbert Morrison, Clement Attlee and Hugh Gaitskell (July, 1951)

Mikardo had an uneasy relationship with Aneurin Bevan who joined the Keep Left group after resigned from the government on 21st April, 1951, when Hugh Gaitskell, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that he intended to introduce measures that would force people to pay half the cost of dentures and spectacles and a one shilling prescription charge. (22)

"The trouble with Nye (Bevan) was that he wasn't a team-player: that was a defect which often worried me and occasionally irritated me, though sometimes I wondered me and occasionally irritated me, though sometimes I wondered whether it was too much to expect a man of his incomparable political genius, of the statue head and shoulders above the rest of us and of everyone around him, to have the patience, the restraint, the self-abnegation that teamwork demands." (23)

Richard Crossman agreed with Mikardo and believed Bevan only wanted a group of compliant followers to amplify his own concerns: "He (Bevan) is an extraordinary mixture of withdrawnness and boldness, and he is always advising Ian Mikardo against rushing into action... He cannot stand the idea of uniting with Morrison and Gaitskell. Yet, on the other hand, when it comes to the point, he jibs at each fighting action as you propose it." (24)

The following month, Crossman wrote in his diary: "Nye is an individualist who, however, is an extraordinary pleasant member of a group. But the last thing he does is to lead it. He dominates its discussions simply because he is fertile in ideas, but the leadership and organisation are things he instinctively shrinks away from." (25)

Denis Healey, a former member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), argued against the policies of Mikardo and Bevan. In 1951 he wrote. "Further 'soaking of the rich' will no longer benefit the poor to any noticeable extent. Further nationalisation no longer attracts more than a tiny fringe of the Labour Party itself; it positively repels the electorate as a whole... A policy based on class war cannot have a wide appeal when the difference between classes is so small as Labour has made it." (26)

In the 1951 General Election the Labour Party won only 295 seats against 302 for the Conservative Party and Winston Churchill became the next prime minister. "In retrospect 1951 was a critical defeat because it put the Conservatives into office at the start of the prosperity and consumerism of the 1950s." (27)

In February 1958 Mikardo joined Konni Zilliacus, Michael Foot, Sydney Silverman, Stephen Swingler, Harold Davies and Walter Monslow, to form Victory for Socialism (VFS). According to Anne Perkins this was an attempt to support Aneurin Bevan in his struggles with Hugh Gaitskell: "the mission was to revive the Bevanite left in the constituencies, called for Gaitskell to go, triggering a vote of no confidence among Labour MPs." (28)

Mikardo worked very closely with Jo Richardson. It was the opinion of Richard Crossman that for all the "charisma of Aneurin Bevan and for all the organising skill of Ian Mikardo and for all the intellect of the members, the Keep Left and Bevanite groups would never have been the force they were but for the workhorse energies" of Jo Richardson, that "ever-persistent and beautiful girl with the flaming red hair". (29)

Labour Government: 1964-1970

Mikardo supported Harold Wilson in his struggle with the leadership of the Labour Party. Wilson later commented: "In this unhealthy atmosphere, the Gaitskellites were seeking their revenge. Their leader, far from discouraging them, was spurring them on, and some were aiming at expelling those who disagreed with him. A few of us, Barbara Castle, lan Mikardo and myself, felt that we should form a small tight group to work out our strategy and our week-by-week tactics. I was elected leader. We met at half-past one every Monday. I set myself the task of resisting extremism and provocative public statements." (30)

Mikardo was defeated in Reading by his Conservative opponent by 3,942 votes in 1959 General Election. "While out of parliament he focused his considerable energies on the development of his private business as an entrepreneur specializing in trade with the Soviet bloc, ably assisted by his secretary, Jo Richardson. His business activities led him to establish close relations with officials from the Soviet Union and eastern Europe, which reinforced the suspicion with which he was viewed by his Conservative opponents, and by many on the right wing of the Labour Party." (31)

Mikardo returned to the House of Commons when he won the safe-seat of Poplar in the 1964 General Election. He was also a member of the national executive committee of the Labour Party during this period. George Wigg advised Harold Wilson to appoint Ian Mikardo and Michael Foot to his Cabinet. Although he agreed that both men were talented he feared that as they were men of principal, if he introduced policies that they considered to be anti-socialist, they would cause him embarrassment by resigning from the government. (32)

Final Years

Tam Dalyell has argued that not giving "Mikardo ministerial office was a profound mistake and seen as an outrage by Labour activists up and down the country". (33) Mikardo continued to play an important role in the House of Commons and was chairman of the Select Committee on Nationalized Industries (1966-70) and chairman of the Labour Party (1970-71). In the 1974 General Election Mikardo was elected to represent Bethnal Green. (34)

Mikardo strongly disapproved when the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey, controversially began imposing tight monetary controls. The government's economic policies included deep cuts in public spending on education and health. Healey accused Mikardo of being "out of his tiny Chinese mind". (35) According to The Times "he had become - from his power base in the Tribune group - in effect the leader of the internal opposition to the government". (36)

Healey was unable to solve Britain's economic problems and in 1976 Healey was forced to obtain a $3.9 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. When Harold Wilson resigned that year, Healey stood for the leadership but was defeated by James Callaghan. The following year Healey controversially began imposing tight monetary controls. This included deep cuts in public spending on education and health. Critics claimed that this laid the foundations of what became known as monetarism. In 1978 these public spending cuts led to a wave of strikes (winter of discontent) and the Labour Party was easily defeated in the 1979 General Election. (37)

In 1980 Denis Healey once again contested the leadership of the Labour Party. The left campaigned against his nomination. Mikardo argued in his autobiography Back Bencher (1988): "When the leadership election loomed in 1980 my friends in the Tribune Group and many other people in the Party and the trade unions wanted to stop Healey because he was way out to the Right and was likely to go even further than Wilson and Callaghan in leading the Party away from its socialist principles. But even though I shared that view I had an even stronger motivation for frustrating his leadership bid. I had seen at first hand his emery-paper abrasive manner, his crude strong-arm all-in-wrestling ways of dealing with dissent, his undisguised contempt for many of his colleagues, his actual enjoyment of confrontation, his penchant for pouring petrol on the flames of controversy, and I was thoroughly convinced that if he became Leader of the Party it wouldn't be long before these aggressive characteristics of the would split the Party from top to bottom; and that was a prospect which scared me." Mikardo helped Michael Foot to be elected as leader. (38)

Ian Mikardo retired from the House of Commons in 1987 and he published his autobiography under the title Back Bencher (1988). In his final years he moved to Cheadle, Cheshire. Suffering from sarcoma and chronic obstructive airways disease, he died on 6th May 1993 at the Stepping Hill Hospital, Stockport, after a stroke.

Primary Sources

(1) Tam Dalyell, The Independent (6th May, 1993)

Both Mikardo's parents came to Britain in the massive Jewish exodus from the Tsarist empire in the last decades of the 19th century and the first of the 20th. His mother, Bluma, came from a village called Yampol in western Ukraine. His father, Morris, Anglicised from Moshe, arrived at the time of the Boer War from Kutno, a textile-manufacturing town to the west of Warsaw. When Morris disembarked in London his total possessions were the clothes that he stood up in plus a little bag containing a change of shirt and underclothes, his accessories for prayer and one rouble. They went to the East End of London, which their son was to represent in Parliament with such distinction from 1964 until 1987.

His parents left the East End and set up home in Portsmouth in 1907. Mikardo was born a year later. He recalled that the language of the family in those early days was Yiddish. When Mikardo went to school at the age of three he had only a few words of English and that put him at a disadvantage in relation to his classmates. He used to tell his many friends in the House of Commons how when he became a Member of Parliament for a constituency containing many Bangladeshi families whose young children had only a few words of English, and saw them harassed by having to study the usual range of school studies whilst they were unfamiliar with the language of their teachers and textbooks, he well understood what they were up against.

His mother's ambition for him was that he should become a rabbi and therefore he went to the Aria College in Portsmouth which had been set up 'for the training and maintenance of young men, natives of the County of Hampshire as Jewish divines on orthodox principles'. However he transferred to Portsmouth Grammar School and in the 1920s shuffled from job to job. He used to tell of how his greatest pleasure was to go and watch Pompey playing football. My wife's great-uncle Jimmy Nichol was one of the Portsmouth half-backs of the decade and I can bear out Mikardo's encyclopaedic knowledge retained after half a century and more of Pompey's games in those halcyon days.

In 1930 he met Mary Rosette, to be his lifelong partner for over 60 years, and as he put it 'found a new family in hers'. He joined the Labour Party and at the same time Poale Zion, the Zionist Workers' Movement which was affiliated to the party. For most of the time he was engaged in little political activity because as with so many others during the Great Depression the mundane grind of earning a living left little time or energy or resources for anything else. By 1935 he had returned to Stepney, where both his daughters were born...

As pamphleteer - his most famous were Keep Left (1947) and Keeping Left (with Dick Crossman, Michael Foot, Jo Richardson, 1950) - new Fabian essayist, staunch friend of Israel, a formidably active member of the NEC of the Labour Party for three decades, and as friend and mentor to many in the Labour movement, Mikardo made a vast impact. My own abiding memory of Mik will be those six-hour sessions in 1984 when he was engaged on 'the last proper thing I will do' in his modest three-roomed apartment on an eighth floor in St John's Wood, producing the Select Committee on Foreign Affairs minority report on the sinking of the Belgrano. In open- necked lumberjack's checked shirt, his foul pipe dangling from this mouth, his beloved Mary in the bedroom (no man was a kinder husband to a then disabled wife), Mik would interrogate his group - Nigel Spearing, Dennis Canavan, Paul Rogers and myself - with the sharpness of a man half a century younger.

(2) Ian Mikardo, Richard Crossman and Michael Foot, Keep Left (1947)

The recent setting up of an overall planning mechanism shows that, for more than a year and a half, we have been without an adequate overall planning mechanism. Even now, there is room for some doubt whether this task is being taken seriously enough. Such a planning mechanism, to be successful, needs to be able not merely to co-ordinate the work of the departments of State but also to reconcile conflicts of view between them, and even to override them when the need arises. For this purpose, it must be headed by a Minister who can give the necessary time to the job, and who has a position and prestige above those of the departmental Ministers. We haven't got that yet.But even more important is the relationship between the overall planning machine and the individual departments of State. This is a problem in management which is by no means confined to the business of government: it is the standard problem of every organisation which has both planning and executive functions. In individual businesses the relationship between "staff" departments, who determine the methods, and "line" departments, who put the methods into operation, has been the subject of continuous and intense study over the last fifty years or more. All that study has led to conclusions which are violated by the new planning mechanisms announced by the Prime Minister a few weeks ago, which is based on the principle of departmental autonomy. This is simply trying to eat your cake and have it, to plan without interfering with preconceptions; and its result is not to integrate the planning machine into the executive machine, but to make it a superstructure which adds to the weight without supplying a compensating increase in power. Departmental autonomy never works in practice, as any managing director knows who has had to resolve conflicts of view between the sales manager, the works manager, the personnel manager, and the accountant; and as the Prime Minister discovered when, in the fuel crisis, he had to set up a special organism which overrode the normal interdepartmental machinery.

(3) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986)

In this unhealthy atmosphere, the Gaitskellites were seeking their revenge. Their leader, far from discouraging them, was spurring them on, and some were aiming at expelling those who disagreed with him. A few of us, Barbara Castle, lan Mikardo and myself, felt that we should form a small tight group to work out our strategy and our week-by-week tactics. I was elected leader. We met at half-past one every Monday. I set myself the task of resisting extremism and provocative public statements.

For MPs to meet in unofficial groups, getting together informally, as distinct from in committees and sub-committees set up by the House of Commons itself, is probably as old as Parliament itself. King John could have written a thesis on the subject. But this was too much for Hugh Gaitskell, who would have been better advised to acknowledge that he led an unofficial group of his own. Immediately after the annual conference at Morecambe in 1952 he found his voice.

In a speech at Stalybridge, he repeated an allegation that one-sixth of the constituency party delegates at Morecambe were communist or communist-inspired. He drew the conclusion that at a time when communist policy was to infiltrate the Labour movement, the Bevanites were assisting them by their disruptive activities. Then, in a direct reference to us and our pamphlets, he went on: "It is time to end the attempt at mob rule by a group of frustrated journalists and restore the authority and leadership of the solid, sound, sensible majority of the movement.' He referred to 'the stream fit grossly misleading propaganda, with poisonous innuendoes and malicious attacks on Atlee, Morrison and the rest of the leadership."

(4) Michael Foot, Aneurin Bevan (1973)

Since the opening of the new session the Bevanites had sought to organize themselves into a more effective parliamentary group. On the suggestion of Ian Mikardo and on the precedent of the Keep Left group, it was agreed to elect a regular chairman - Harold Wilson was the first - and to meet at a regular time in the parliamentary week: 1.30 on Mondays. None of those participating in these secret rites thought at the outset that they might be indulging in some scandalous Mau Mau activity - (none at least except the compulsive informer in our midst who reported our proceedings regularly to Hugh Dalton and thereby to the Whips). Unofficial groups had existed in Parliament ever since the first Witenagemot, and the Bevanites of the early 1950s imagined they were following a more recent precedent set by others, notably the XYZ Club, which had been talking politics over exclusive dinner tables since its foundation by Douglas Jay and a few others in the early 1940s. No one, after all, had ever suggested that the Keep Left group should be outlawed. By January 1952 the new Bevanite arrangements were in full working order and the agenda was crowded.

(5) Ian Mikardo, speech (31st October 1952)

I rejoice that we are not going to have any more personal attacks by members of the Parliamentary Labour Party on other members of the Parliamentary Labour Party. Never again, O my exhuberant heart, will I be referred to as one of "a band of splenetic furies". I rejoice.

Never again will there be talk of "parlour revolutionaries and other mischief-makers". That's a great step forward.

No more, never ever more, will those who write about Nye Bevan include me in the list of "sycophantic friends about him". Let us praise this day for evermore. For never again will even the more eminent amongst us refer to some of his comrades as "extreme Left-wingers… some with outlooks soured and warped by disappointment of personal ambitions, some highbrows educated beyond their capacity".

I rejoice at this new upsurge of self-restraint, even though it will undoubtedly rob us of many lambent pearls of English literature. We shall, for instance, have to sigh in vain for any more like "an uneasy coalition of well-meaning emotionalists, frustrates, crackpots and fellow-travellers, making Fred Karno's Army look like the Brigade of Guards.

But it ensures that we don't ever again hear some sizeable fraction of the constituency delegates to the party Conference (who include many Labour M.P.s) as appearing "to be Communist or Communist-inspired", or the proceedings of that Conference characterised as "mob rule by a group of frustrated journalists".

(6) Ian Mikardo, statement issued after the death of Konni Zilliacus (27th July, 1967)

Zilly was in many ways the greatest international Socialist of my time. It is for that reason, and only for that reason, he earned the distinction of being refused a visa to the United States, and being refused a visa to the Soviet Union, and of being expelled from the Labour Party all within the same year. He never gave up fighting for the principles of the United Nations, based on the all-inclusive covenants of the Charter, no matter who opposed him, whether it was Ernest Bevin or Wall Street or Stalin. He was completely devoted in the best sense to the socialist causes which are the basis of peace.

In a way Zilly was a non-politician. Most people who didn't know him personally but knew him only from reading what he wrote and reading about him, would think of him pre-eminently as a politician, but he really wasn't. He was a man of political ideas, but he wasn't very good at politics. The tactics, the ritual dances of parliamentary procedure and the order paper, were in a language that wasn't contained within the eleven he spoke. They were all foreign to him and when it really came to the tough stuff and the in-fighting I sometimes thought of Zilly as a child walking around a jungle of man-eating animals. That's why he was more than once such an easy victim for the hatchet men. Zilly was preeminently an analyst, perhaps unparalleled as a political analyst, and perhaps even more than that a teacher, a great teacher, and not only those like myself of his own generation learned at his feet, but the next generation of people in our movement derived a great deal from him and many of the new, younger men we have had in the House of Commons in the last three years know a great deal of what they know because of what they learned from Zilly.

(7) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988)

In the meanwhile the Callaghan Government dragged to its miserable close, and after its suicide in 1979 it was clear that Jim would resign from his office as Leader within the next year or eighteen months. When the time actually came, in October 1980, the question of who was to succeed him was complicated by the fact that, while the constitution provided that the Leader and his Deputy were elected by the Parliamentary Party alone, there was a proposal before the Party to amend the constitution so as to widen the franchise by setting up an electoral college of the PLP plus the Constituency Parties plus the trade unions, and that amendment was due to be put to a special Party Conference to be held a few months later.

The Left in the PLP were keen to postpone the election of a new Leader till then by appointing the current Deputy Leader, Michael Foot, as a caretaker for the short period up to the constitutional conference. The Right, by contrast, wanted the election held at once by the PLP alone, because they could be expected to elect the Right's favoured candidate, Denis Healey. Some of Callaghan's ex-Ministers issued statements in support of this proposal: they included three or more of those who later became the Gang of Four and a number of their friends who also defected to the SDP. They got their way, and the election went ahead with the PLP as the electoral constituency.

To go back to the beginning, Jim announced his resignation to the Shadow Cabinet at their regular Wednesday afternoon meeting on 15 October 1980. As soon as he'd finished his resignation statement Michael Foot paid a long and warm tribute to him. (Michael had characteristically given continuously faithful and selfless loyalty to Jim throughout the two turbulent years of Jim's premiership, and Jim returned evil for good by undermining Michael's leadership during the 1983 election campaign.) After the Shadow Cabinet meeting three of the left wing members of the Shadow Cabinet and one semi-left winger - Albert Booth, Stan Orme, John Silkin and Peter Shore - went off to Silkin's room to discuss what to do next. The remaining two of their little group, Michael himself and Tony Benn, were tied up and weren't able to attend. The four who were there agreed that their objective must be to try to prevent the election of Denis Healey: Peter Shore said that he thought he had a good chance of beating Denis; John Silkin went much further and claimed confidently that he would certainly beat Healey and anyone else who might stand.

The stop-Healey urge was one which I shared in full measure, but more than once I asked myself sharply why I was so keen to keep out of the Party's top position a man for whom I had, as I still have, great admiration and a very high regard. Denis is an outstanding talent, equalled by very few people I've met in the whole of my long innings. When he speaks on international affairs, he speaks with the authority that derives from an unmatched knowledge of what's going on in almost every country in the world, and his analysis of all those movements of events is almost always penetrating and enlightening. He is a cultured man of parts, of many interests outside politics (those politicians whose lives contain nothing but politics are always second-class politicians). He's a bubbly, witty man who can be a charming and entertaining companion.

Now that he has mellowed, as we all do (not least I) after we get our senior-citizens' bus-passes, he exudes the milk of human kindness; but in the 1960s and 1970s he was a political bully wielding the language of sarcasm and contempt like a caveman's cudgel. He didn't argue with those members of the Party who didn't agree with him, he just wrote them off. He once described a Cabinet colleague who dared to differ from him as having a "tiny Chinese mind". More than once, in my own arguments with him, he didn't reply to what I'd said but instead quoted me as saying something nonsensical which I had never said. He knew all the tricks, and used them ruthlessly.

When the leadership election loomed in 1980 my friends in the Tribune Group and many other people in the Party and the trade unions wanted to stop Healey because he was way out to the Right and was likely to go even further than Wilson and Callaghan in leading the Party away from its socialist principles. But even though I shared that view I had an even stronger motivation for frustrating his leadership bid. I had seen at first hand his emery-paper abrasive manner, his crude strong-arm all-in-wrestling ways of dealing with dissent, his undisguised contempt for many of his colleagues, his actual enjoyment of confrontation, his penchant for pouring petrol on the flames of controversy, and I was thoroughly convinced that if he became Leader of the Party it wouldn't be long before these aggressive characteristics of the would split the Party from top to bottom; and that was a prospect which scared me.

References

(1) Tam Dalyell, Ian Mikardo : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) pages 7-8

(3) Tam Dalyell, Ian Mikardo : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(4) Tam Dalyell, The Independent (6th May, 1993)

(5) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) pages 53-54

(6) Tam Dalyell, Ian Mikardo : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(7) John Campbell, Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) page 136

(8) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) page 77

(9) Winston Churchill, radio broadcast (4th June, 1945)

(10) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) page 84

(11) Clement Attlee, radio broadcast (5th June, 1945)

(12) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) page 84

(13) Ben Pimlott, Hugh Dalton (1985) page 596

(14) Hugh Dalton, diary entry (12th April, 1946)

(15) The Independent (22nd May 1993)

(16) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) page 293

(17) Ian Mikardo, Richard Crossman and Michael Foot, Keep Left (1947)

(18) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) pages 118-119

(19) Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein, The Labour Party: A Marxist History (1988) page 239

(20) John Campbell, Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) page 136

(21) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) page 293

(22) Michael Foot, Aneurin Bevan: 1945-1960 (1973) pages 329-349

(23) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) pages 118-119

(24) Richard Crossman, diary entry (26th November, 1951)

(25) Richard Crossman, diary entry (17th December, 1951)

(26) Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (1989) page 150

(27) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) page 301

(28) Anne Perkins, Red Queen (2003) page 173

(29) Tam Dalyell, The Independent (2nd February, 1994)

(30) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986) page 137

(31) Tam Dalyell, Ian Mikardo : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(32) George Wigg, Autobiography (1972) page 308

(33) Tam Dalyell, The Independent (6th May, 1993)

(34) Tam Dalyell, Ian Mikardo : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(35) Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (1989) page 444

(36) The Times (7th May, 1993)

(37) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) page 360

(38) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988) pages 118-119