Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

President Calvin Coolidge announced in August 1927 that he would not seek a second full term of office. Coolidge was unwilling to nominate Herbert Hoover as his successor. The two men had a poor relationship on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice - all of it bad. I was particularly offended by his comment to 'shit or get off the pot'." (1)

Coolidge was not alone in thinking that Hoover might be a bad candidate. Republican leaders cast about for an alternative candidate such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and the former Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Despite these reservations, Hoover won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas was selected as his running-mate. One newspaper reported: "Hoover brings character and promise to the Republican ticket. He is a new kind of candidate in a day surfeited with old forms and old habits in politics." (2)

1922 Fordney-McCumber Act

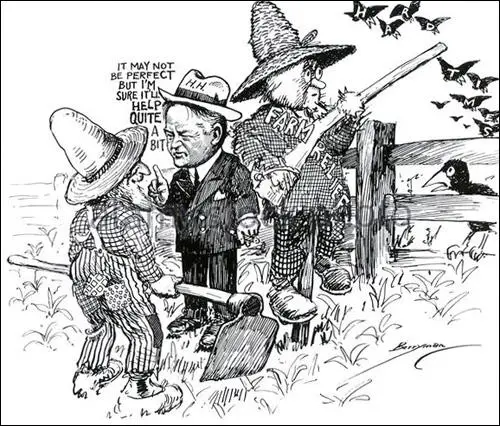

One of the main issues in the election campaign was the taxes imposed on imports. The Fordney-McCumber Act of 1922. This authorized the "Tariff Commission, working in an 'expert' and unpolitical way (and thus supposedly also independently of economic interests), to set rates so as to equalize the difference between American and foreign costs of production." (3)

It raised tariffs to levels higher than any previously in American history in an attempt to bolster the post-war economy, protect new war industries, and aid farmers. "Duties on chinaware, pig iron, textiles, sugar, and rails were restored to the high levels of 1907 and increases ranging from 60 to 400 per cent were established on dyes, chemicals, silk and rayon textiles, and hardware." (4)

In response to the Fordney-McCumber, most of American trading partners had raised their own tariffs to counter-act this measure. The Democratic Party that had opposed tariffs argued that it was to blame for the agricultural depression that took place during the 1920s. Senator David Walsh pointed out that farmers were net exporters and so did not need protection. He explained that American farmers depended on foreign markets to sell their surplus. The price of farming machinery also increased. For example, the average cost of a harness rose from $46 in 1918 to $75 in 1926, the 14-inch plow rose from $14 to $28, mowing machines rose from $45 to $95, and farm wagons rose from $85 to $150. Statistics of the Bureau of Research of the American Farm Bureau that showed farmers had lost more than $300 million annually as a result of the tariff. (5)

Although agriculture sector had problems during the 1920s, American industry prospered. The real wages of industrial workers increased by about 10 per cent during this period. However, productivity rose by more than 40%. Semi-skilled and unskilled workers in mass production, who were not unionized, lagged far behind skilled craftsmen and therefore was a growth in inequality: "The average industrial wage rose from 1919's $1,158 to $1,304 in 1927, a solid if unspectacular gain, during a period of mainly stable prices... The twenties brought an average increase in income of about 35%. But the biggest gain went to the people earning more than $3,000 a year.... The number of millionaires had risen from 7,000 in 1914 to about 35,000 in 1928." (6)

Hoover and the Republicans believed the Forder-McCumber tariffs had helped the American economy to grow. William Borah, the charismatic senator from Idaho, widely regarded as a true champion of the American farmer, had a meeting with Hoover and offered to give him his full support if he promised to increase tariffs of agricultural products if elected. (7) Hoover agreed with the proposal and during the campaign promised the American electorate that he would revise the tariff. (8)

Carter Field argued that the business community was pleased with the election of Hoover: "In the months following the election of Hoover, in 1928, there was a wild stock-market boom. Most speculators, most businessmen, most people thought the country was moving on to a new high plateau of prosperity. Hoover was the miracle man. He knew about business and would help it prosper. Stocks were already high the day Hoover was elected; for example, American Telephone, which was sold around 150 in the spring of 1927 and was about 200 on election day, 1928, soared to a high above 310." (9)

1930 Smoot-Hawley Act

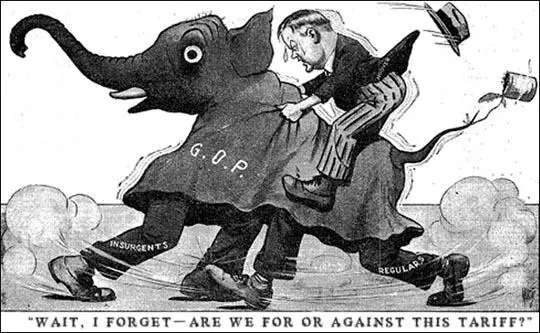

After his election Hoover asked Congress for an increase of tariff rates for agricultural goods and a decrease of rates for industrial goods. Reed Smoot from Utah and chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and Willis C. Hawley, from Oregon, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, agreed to sponsor the proposed bill. Individual members of Congress were under great pressure from industry lobbyists to raise tariffs to protect them from the negative effects of foreign imports. Therefore, when it passed by the House of Representatives the president's bill was completely changed and now included rate hikes covering 887 specific products. (10)

Patrick Renshaw has pointed out: "The real problem was that in both agricultural and industrial sectors of the economy America's capacity to produce was tending to outstrip its capacity to consume. This gap had been partly bridged by private debt, easy credit, easy credit and hire purchase. But this would collapse if anything went wrong in another part of the system." (11) Smoot and Hawley argued that raising the tariff on imports would alleviate the over-production problem. In May 1929, the House of Representatives passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff bill on a vote of 264 to 147, with 244 Republicans and 20 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. (12)

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff bill was then debated in the Senate. It came under attack from Democrats. Reed Smoot defended the bill by arguing: "This government should have no apology to make for reserving America for Americans. That has been our traditional policy. ever since the United States became a nation. We have returned to participate in the political intrigues of Europe, and we will not compromise the independence of this country for the privilege of serving as schoolmaster for the world. In economics as in politics, the policy of the government is, "America First". The Republican Party will not stand by and see economic experimenters fritter away our national heritage." (13)

The Senate debated its bill until March 1930, with many Senators trading votes based on their states' industries. Eventually, the revised bill proposed raising taxes on more than 20,000 imported goods to record levels. Willis C. Hawley predicted that it would bring "a renewed era of prosperity". Another supporter, Frank Crowther, argued that "business confidence will be immediately restored. We shall gradually work out of the temporary slump we have been in for the last few months... We shall dissipate the dark clouds of your gloomy prophecy with the rising sunshine of continued prosperity." (14)

The Smoot-Hawley bill was passed in the Senate on a vote of 44 to 42, with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. In an attempt to persuade Hoover to veto the legislation, 1,028 American economists, including Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, who was considered the most important economist of the period, published a open letter on the subject. (15)

"We are convinced that increased protective duties would be a mistake. They would operate, in general, to increase the prices which domestic consumers would have to pay. By raising prices they would encourage concerns with higher costs to undertake production, thus compelling the consumer to subsidize waste and inefficiency in industry. At the same time they would force him to pay higher rates of profit to established firms which enjoyed lower production costs. A higher level of protection, such as is contemplated by both the House and Senate bills, would therefore raise the cost of living and injure the great majority of our citizens."

The letter went on to point out that since the Wall Street Crash had resulted in much higher-rates of unemployment: "America is now facing the problem of unemployment. Her labor can find work only if her factories can sell their products. Higher tariffs would not promote such sales. We can not increase employment by restricting trade. American industry, in the present crisis, might well be spared the burden of adjusting itself to new schedules of protective duties. Finally, we would urge our Government to consider the bitterness which a policy of higher tariffs would inevitably inject into our international relations. The United States was ably represented at the World Economic Conference which was held under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1927. This conference adopted a resolution announcing that 'the time has come to put an end to the increase in tariffs and move in the opposite direction.' The higher duties proposed in our pending legislation violate the spirit of this agreement and plainly invite other nations to compete with us in raising further barriers to trade. A tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace." (16)

Henry Ford spent an evening at the White House trying to convince Hoover to veto the bill, calling it "an economic stupidity." Thomas W. Lamont, the chief executive of J. P. Morgan Investment Bank said he "almost went down on his knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot tariff." He warned that the act would intensify "nationalism all over the world.” (17)

President Hoover considered the bill "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious" but according to his biographer, Charles Rappleye, "the president could hardly turn its back on a measure endorsed by a clear majority of his own party." (18) Hoover signed the bill on 17th June, 1930. The Economist Magazine argued that the passing of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was "the tragic-comic finale to one of the most amazing chapters in world tariff history… one that Protectionist enthusiasts the world over would do well to study.” (19)

At the time the Smoot-Hawley bill was passed the United States had 4.3 million unemployed. By 1932 it was 12.0 million. The economist, David Blanchflower, has argued that the "Smoot-Hawley Tariff proved to be the most damaging piece of trade legislation in US history." (20)

1934 Reciprocal Tariff Act

In 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Cordell Hull as his Secretary of State. Hull considered himself as an internationalist and was a strong advocate of free trade. Hull regarded himself as a follower of the economic theories of Adam Smith and as a disciple of "Locke, Milton, Pitt, Burke, Gladstone, and the Lloyd George school." (21)

Hull knew that America would never adopt free trade but believed the best policy was to empower Roosevelt to negotiate agreements with no other nations to lower duties. In 1934 Hull won the support of Henry Wallace, Secretary of Agriculture, who argued in a pamphlet, America Must Choose: The Advantages and Disadvantages of Nationalism, of World Trade, and of a Planned Middle Course (1934), that the only alternative to burgeoning foreign trade was a controlled economy. (22)

President Roosevelt was now convinced the Smoot-Hawley Tariff had played a significant role in the Great Depression. He believed that Congress should not be directly involved in such issues. On 2nd March, 1934, Roosevelt asked Congress for authority to negotiate tariff agreements. "Other governments are to an ever-increasing extent winning their share of international trade by negotiated reciprocal trade agreements. If American agricultural and industrial interests are to retain their deserved place in this trade, the American government must be in a position to bargain for the place with other governments by rapid and decisive negotiation based upon a carefully considered program, and to grant with discernment corresponding opportunities in the American market for foreign products supplementary to our own. If the American government is not in a position to make fair offers for fair opportunities, its trade will be superseded. If it is not in a position at a given moment rapidly to alter the terms on which it is willing to deal with other countries, it cannot adequately protect its trade against discriminations and against bargains injurious to its interests." (23)

The President's request met strenuous opposition from business interests and from Republican congressmen, who objected both to lowering duties and to surrendering yet another congressional prerogative. (24) However, as Cordell Hull pointed out: "In both House and Senate we were aided by the severe reaction of public opinion against the Smoot-Hawley Act." (25)

On 29th March, the House of Representatives, adopted the bill 274-111, only two Republicans voted for it. The Democrats also controlled the Senate and the Reciprocal Tariff Act was passed on 12th June. This gave power to the president to raise or lower existing tariff rates up to 50 per cent for countries which would reciprocate with similar concessions for American products. In the next four years, Hull concluded eighteen such treaties. (26)

Businessmen like James D. Mooney, vice-president of General Motors, and Thomas A. Morgan, president of Curtiss-Wright, urged Roosevelt to recognition of the Soviet Union. They believed that it would lead to a revival of trade with the world's largest buyer of American industrial and agricultural equipment. Catholic leaders opposed any action that might appear to sanction bolshevism, Roy Wilson Howard, head of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, observed: "I think the menace of Bolshevism in the United States is about as great as the menace of sunstroke in Greenland or chilblains in the Sahara." Thomas J. Watson, president of International Business Machines, asked every American, in the interest of good relations, to "refrain from making any criticism of the present form of Government adopted by Russia." (27)

Trade Tariffs since the Second World War

Reciprocity was an important tenet of the trade agreements brokered under RTAA because it gave Congress more of an incentive to lower tariffs. As more foreign countries entered into bilateral tariff reduction deals with the United States, American exporters had more incentive to lobby Congress for even lower tariffs across many industries. President Dwight Eisenhower admitted that when he came to power some congressional Republicans "were unhappy with the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, and a few even hoped we could restore the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, a move which I knew would be ruinous." (28)

By the time President Lyndon Baines Johnson came to power the debate over tariffs seemed to be over: "What captain of industry or what union leader in this country really yearns and is eager to return to the days of Smoot-Hawley? For the world of you-know-what-deep depressions, rampant unemployment, low profits, if any and, generally, losses... Any move to raise tariffs would set a chain reaction of counter-protection and retaliation that would put in jeopardy our ability to work together and to prosper together... The days of declining trade barriers in a world of unprecedented prosperity and growth is something we want to continue." (29)

As Douglas A. Irwin, the author of Peddling Protectionism: Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression (2017) pointed out: "The Tariff of 1930 proved to be the last time Congress ever determined the specific rates of duty that applied to U.S. imports. Since World War II, a series of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements have reduced U.S. tariffs to levels that would have shocked Smoot and Hawley. Whereas the average tariff on dutiable imports was 45 per cent in 1930, it was less than 5 per cent in 2010." (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Rappleye, Herbert Hoover in the White House: The Ordeal of the Presidency

(2017)

Of all the imbroglios to mar Hoover's first, extended encounter with the Congress, the tariff was perhaps the most costly. It dragged on incessantly, it brought out the worst of the legislators, and it highlighted Hoover's weakness as a leader - all in service of a bill that nobody much liked in the end.

The final version of the tariff bill authored by Utah senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willie Hawley of Oregon, engaged in wholesale rate hikes covering 887 specific products - a far cry from the limited revision first proposed by Hoover. After winning House approval in May, the bill engendered a groundswell of protest, including a public letter from 1,028 economists demanding a Hoover veto. But that was impossible; having stood by as the bill made it tortuous way through Congress, the president could hardly turn its back on a measure endorsed by a clear majority of his own party.

(2) A public letter signed by 1,028 American economists (May, 1930)

The undersigned American economists and teachers of economics strongly urge that any measure which provides for a general upward revision of tariff rates be denied passage by Congress, or if passed, be vetoed by the President.

We are convinced that increased protective duties would be a mistake. They would operate, in general, to increase the prices which domestic consumers would have to pay. By raising prices they would encourage concerns with higher costs to undertake production, thus compelling the consumer to subsidize waste and inefficiency in industry. At the same time they would force him to pay higher rates of profit to established firms which enjoyed lower production costs. A higher level of protection, such as is contemplated by both the House and Senate bills, would therefore raise the cost of living and injure the great majority of our citizens.

Few people could hope to gain from such a change. Miners, construction, transportation and public utility workers, professional people and those employed in banks, hotels, newspaper offices, in the wholesale and retail trades, and scores of other occupations would clearly lose, since they produce no products which could be protected by tariff barriers.

The vast majority of farmers, also, would lose. Their cotton, corn, lard, and wheat are export crops and are sold in the world market. They have no important competition in the home market. They can not benefit, therefore, from any tariff which is imposed upon the basic commodities which they produce. They would lose through the increased duties on manufactured goods, however, and in a double fashion. First, as consumers they would have to pay still higher prices for the products, made of textiles, chemicals, iron, and steel, which they buy. Second, as producers, their ability to sell their products would be further restricted by the barriers placed in the way of foreigners who wished to sell manufactured goods to us.

Our export trade, in general, would suffer. Countries can not permanently buy from us unless they are permitted to sell to us, and the more we restrict the importation of goods from them by means of ever higher tariffs the more we reduce the possibility of our exporting to them. This applies to such exporting industries as copper, automobiles, agricultural machinery, typewriters, and the like fully as much as it does to farming. The difficulties of these industries are likely to be increased still further if we pass a higher tariff. There are already many evidences that such action would inevitably provoke other countries to pay us back in kind by levying retaliatory duties against our goods. There are few more ironical spectacles than that of the American Government as it seeks, on the one hand, to promote exports through the activity of the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, while, on the other hand, by increasing tariffs it makes exportation ever more difficult. President Hoover has well said, in his message to Congress on April 16, 1929, “It is obviously unwise protection which sacrifices a greater amount of employment in exports to gain a less amount of employment from imports.”

We do not believe that American manufacturers, in general, need higher tariffs. The report of the President’s committee on recent economics changes has shown that industrial efficiency has increased, that costs have fallen, that profits have grown with amazing rapidity since the end of the war. Already our factories supply our people with over 96 percent of the manufactured goods which they consume, and our producers look to foreign markets to absorb the increasing output of their machines. Further barriers to trade will serve them not well, but ill. Many of our citizens have invested their money in foreign enterprises. The Department of Commerce has estimated that such investments, entirely aside from the war debts, amounted to between $12,555,000,000 and $14,555,000,000 on January 1, 1929. These investors, too, would suffer if protective duties were to be increased, since such action would make it still more difficult for their foreign creditors to pay them the interest due them.

America is now facing the problem of unemployment. Her labor can find work only if her factories can sell their products. Higher tariffs would not promote such sales. We can not increase employment by restricting trade. American industry, in the present crisis, might well be spared the burden of adjusting itself to new schedules of protective duties.

Finally, we would urge our Government to consider the bitterness which a policy of higher tariffs would inevitably inject into our international relations. The United States was ably represented at the World Economic Conference which was held under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1927. This conference adopted a resolution announcing that “the time has come to put an end to the increase in tariffs and move in the opposite direction.” The higher duties proposed in our pending legislation violate the spirit of this agreement and plainly invite other nations to compete with us in raising further barriers to trade. A tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace.

(3) Neil Wynn, The A to Z from the Great War to the Great Depression (2009)

Approved by President Herbert Hoover despite the appeals of over a thousand leading economists to reject it, the Hawley-Smoot Tariff raised the tariffs of the Fordney-McCumber Act and set import duties at some of the highest levels in American history. Proposed by Representative Willis Hawley of Oregon and Senator Reed Smoot of Utah, the tariff was intended to help particularly agriculture in the face of falling prices. However, it was extended to cover many aspects of manufacturing industry. Its effects were disastrous as foreign nations introduced their own retaliatory duties leading to a further fall in American and world trade and only increasing the impact of the Depression.

(4) David Blanchflower, New Statesman (24th March, 2011)

The really bad economic idea during the Great Depression, put forward by the Republican senator for Utah Reed Smoot and the Oregon representative Willis Hawley, was to raise taxes on more than 20,000 imported goods to record levels. Ignoring the widespread opposition of economists, the politicians made bold claims as to how the new legislation would transform America's economy. Hawley predicted that it would bring "a renewed era of prosperity". Frank Crowther, a New York Republican representative, said that "business confidence will be immediately restored. We shall gradually work out of the temporary slump we have been in for the last few months... We shall dissipate the dark clouds of your gloomy prophecy with the rising sunshine of continued prosperity."

In May 1930, 1,028 economists signed a petition asking President Herbert Hoover to veto the legislation, but the act became law just a couple of weeks later. Unfortunately, the Republican politicians' predictions were wide of the mark and the economy sank deeper into depression. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff proved to be the most damaging piece of trade legislation in US history.

(5) President Franklin D. Roosevelt, speech to Congress (2nd March, 1934)

Other governments are to an ever-increasing extent winning their share of international trade by negotiated reciprocal trade agreements. If American agricultural and industrial interests are to retain their deserved place in this trade, the American government must be in a position to bargain for the place with other governments by rapid and decisive negotiation based upon a carefully considered program, and to grant with discernment corresponding opportunities in the American market for foreign products supplementary to our own. If the American government is not in a position to make fair offers for fair opportunities, its trade will be superseded. If it is not in a position at a given moment rapidly to alter the terms on which it is willing to deal with other countries, it cannot adequately protect its trade against discriminations and against bargains injurious to its interests.

(6) President Lyndon Baines Johnson, speech (December, 1967)

What captain of industry or what union leader in this country really yearns and is eager to return to the days of Smoot-Hawley? For the world of you-know-what-deep depressions, rampant unemployment, low profits, if any and, generally, losses.

(7) Dominic Rushe, The Observer (29th January 2017)

As America inches towards a potential trade war over steel prices can Donald Trump hear whispering voices? Alone in the Oval Office in the wee dark hours, illuminated by the glow of his Twitter app, does he feel the sudden chill flowing from those freshly hung gold drapes? It is the shades of Smoot and Hawley.

Willis Hawley and Reed Smoot have haunted Congress since the 1930s when they were the architects of the Smoot-Hawley tariff bill, among the most decried pieces of legislation in US history and a bill blamed by some for not only for triggering the Great Depression but also contributing to the start of the second world war.

Pilloried even in their own time, their bloodied names have been brought out like Jacob Marley's ghost every time America has taken a protectionist turn on trade policy. And America has certainly taken a protectionist turn.

Successful presidents including Barack Obama and Bill Clinton have campaigned on the perils of free trade only to drop the rhetoric once installed in the White House. Trump called Mexicans "rapists" on the campaign trail. And China? "There are people who wish I wouldn't refer to China as our enemy. But that's exactly what they are," Trump said.

As commander-in-chief he has shown no signs of softening and this week took major action announcing steel imports would face a 25% tariff and aluminium 10%.

Canada and the EU said they would bring forward their own counter-measures. Mexico, China and Brazil have also said they are considering retaliatory steps.

Trump doesn't seem worried. "Trade wars are good," he tweeted even as the usually friendly Wall Street Journal thundered that "Trump's tariff folly" was the "biggest policy blunder of his Presidency".

It is not his first protectionist move. In his first days in office the president has vetoed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the biggest trade deal in a generation, said he will review the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta), a deal he has called "the worst in history", and had his visit with Mexico's president cancelled over his plans to make them pay for a border wall.

Free traders may have become complacent after hearing tough talk on trade from so many presidential candidates on the campaign trail only to watch them furiously back-pedal when they get into office, said Dartmouth professor and trade expert Douglas Irwin. "Unfortunately that pattern may have been broken," he says. "It looks like we have to take Trump literally and seriously about his threats on trade."

Not since Herbert Hoover has a US president been so down on free trade. And Hoover was the man who signed off on Smoot and Hawley's bill.

Hawley, an Oregon congressman and a professor of history and economics, became a stock figure in the textbooks of his successors thanks to his partnership with the lean, patrician figure of Senator Reed Smoot, a Mormon apostle known as the "sugar senator" for his protectionist stance towards Utah's sugar beet industry.

Before he was shackled to Hawley for eternity Smoot was more famous for his Mormonism and his abhorrence of bawdy books, a disgust that inspired the immortal headline "Smoot Smites Smut" after he attacked the importation of Lady's Chatterley's Lover, Robert Burns' more risqué poems and similar texts as "worse than opium … I would rather have a child of mine use opium than read these books."

But it was imports of another kind that secured Smoot and Hawley's place in infamy.

The US economy was doing well in the 1920s as the consumer society was being born to the sound of jazz. The Tariff Act began life largely as a politically motivated response to appease the agricultural lobby that had fallen behind as American workers, and money, consolidated in the cities.

Foreign demand for US produce had soared during the first world war, and farm prices doubled between 1915 and 1918. A wave of land speculation followed and farmers took on debt as they looked to expand production. By the early 1920s farmers had found themselves heavily in debt and squeezed by tightening monetary policy and an unexpected collapse in commodity prices.

Nearly a quarter of the American labor force was then employed on the land, and Congress could not ignore heartland America. Cheap foreign imports and their toll on the domestic market became a hot issue in the 1928 election. Even bananas weren't safe. Irwin quotes one critic in his book Peddling Protectionism: Smoot Hawley and the Great Depression: "The enormous imports of cheap bananas into the United States tend to curtail the domestic consumption of fresh fruits produced in the United States."

Republicans called protective tariffs "essential for the continued prosperity of the country" and Hoover, who said agriculture was "the most urgent economic problem" facing the nation, said "an adequate tariff is the foundation of farm relief".

Hoover won in a landslide against Albert E Smith, an out-of-touch New Yorker who didn't appeal to middle America, and soon after promised to pass "limited" tariff reforms.

Hawley started the bill but with Smoot behind him it metastasized as lobby groups shoehorned their products into the bill, eventually proposing higher tariffs on more than 20,000 imported goods.

Siren voices warned of dire consequences. Henry Ford reportedly told Hoover the bill was "an economic stupidity".

Critics of the tariffs were being aided and abetted by "internationalists" willing to "betray American interests", said Smoot. Reports claiming the bill would harm the US economy were decried as fake news. Republican Frank Crowther, dismissed press criticism as "demagoguery and untruth, scandalous untruth".

In October 1929 as the Senate debated the tariff bill the stock market crashed. When the bill finally made it to Hoover's desk in June 1930 it had morphed from his original "limited" plan to the "highest rates ever known", according to a New York Times editorial.

The extent to which Smoot and Hawley were to blame for the coming Great Depression is still a matter of debate. "Ask a thousand economists and you will get a thousand and five answers," said Charles Geisst, professor of economics at Manhattan College and author of Wall Street: A History.

What is apparent is that the bill sparked international outrage and a backlash. Canada and Europe reacted with a wave of protectionist tariffs that deepened a global depression that presaged the rise of Hitler and the second world war. A myriad other factors contributed to the Depression, and to the second world war, but inarguably one consequence of Smoot-Hawley in the US was that never again would a sitting US president be so avowedly anti-trade. Until today.

Franklin D Roosevelt swept into power in 1933 and for the first time the president was granted the authority to undertake trade negotiations to reduce foreign barriers on US exports in exchange for lower US tariffs. The backlash against Smoot and Hawley continued to the present day. The average tariff on dutiable imports was 45% in 1930; by 2010 it was 5%.

The lessons of Smoot-Hawley used to be taught in high schools, said Geisst. Presidents from Lyndon Johnson to Ronald Reagan have enlisted the unhappy duo when facing off with free trade critics. "I have been around long enough to remember that when we did that once before in this century, something called Smoot-Hawley, we lived through a nightmare," Reagan, who came of age during the Great Depression, said in 1984.

They even got a mention in Ferris Bueller's Day Off when actor Ben Stein's teacher bores his class with it. "I don't think the current generation are taught it. It's in the past and we are more interested in the future," said Geisst.

But that might be about to change. "The main lesson is that you have to worry about what other countries do. Countries will retaliate," said Irwin. "When Congress was considering Smoot-Hawley in the 1930s they didn't consider what other countries might do in reaction. They thought other countries would remain passive. But other countries don't remain passive."

The consequences of a trade war today are far worse than in the 1930s. Exports of goods and services account for about 13% of US gross domestic product (GDP) – the broadest measure of an economy. It was roughly 5% back in 1920.

"The US is much more engaged in trade, it's much more a part of the fabric of the country, than it was in the 1920s and 1930s. That means the ripple effects are widespread. Many more industries will be hit by it and the scope for foreign retaliation, which in the case of Smoot-Hawley was quite limited, is going to be much more widespread if a trade war was to start," said Irwin.

"When you start talking about withdrawing from trade agreements or imposing tariffs of 35%, if you are doing that as a protectionist measure, that would be blowing up the system."

That the promise of "blowing up the system" got Trump elected may be why the ghosts of Smoot and Hawley are once again walking the halls of Congress.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject