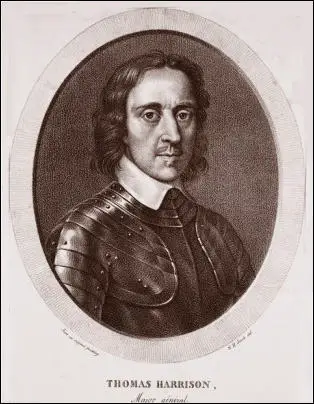

Thomas Harrison

Thomas Harrison, the second of four children and the only son of Richard and Mary Harrison, was born in Newcastle-under-Lyme, in July, 1616. His father was a butcher and four times mayor of the town. He was educated at a local grammar school, and then became a clerk to solicitor Thomas Houlker of Clifford's Inn. (1)

Over the next few years Harrison developed hostile views towards the monarchy and the established church: "The young Harrison found himself associated with a number of young men who helped to frame his mind to opposition to the King and bishops." (2) It has been claimed that during this period he became an Anabaptist. (3)

On 4th January 1642, Charles I sent his soldiers to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London and formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers). His opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads) and it was the beginning of the English Civil War. The Roundheads immediately took control of London. (4)

The English Civil War

In 1642, aged twenty-six, Harrison enlisted in the Parliamentary Army under Edward Montagu, the Earl of Manchester. The following year he served with Charles Fleetwood at Marston Moor (5). The battle lasted two hours. Over 3,000 Royalists were killed and around 4,500 were taken prisoner. The Parliamentary forces lost only 300 men. The city of York surrendered two weeks after the battle, ending Royalist power in the north of England. (6) It is claimed that during this battle Harrison developed a reputation as a "dashing cavalry officer whose rule in warfare was audacity and attack". (7)

Charles H. Simpkinson has pointed out that Harrison was an excellent soldier: "The life of a soldier was very attractive to him, and he loved the danger and excitement of a headlong cavalry charge. At certain moments he exhibited a strange cruelty which brought him into some disgrace. But other men who knew desire to be kind to all with whom he might be brought into contact of whatever class. He had a sense that he was an instrument in the hands of God, and was confident that he had special revelations from the Spirit. It seems as if he was kept in the rank of Major for some time in order that not having too definite a command he might be available to lead the forlorn hope either in politics or in battle." (8)

At the beginning of the war, Parliament relied on soldiers recruited by large landowners who supported their cause. In February 1645, Parliament decided to form a new army of professional soldiers and amalgamated the three armies of William Waller, Earl of Essex and Earl of Manchester. This army of 22,000 men became known as the New Model Army. Its commander-in-chief was General Thomas Fairfax, while Oliver Cromwell was put in charge of its cavalry. According to A. L. Morton, these men were the "equals of Charles' gentlemen riders in courage and infinitely their superiors in discipline." (9)

Thomas Harrison & the Levellers

Major Harrison became associated with progressive elements in the army and became chief in the councils of the Independent Party. (10) This group argued for a policy of religious toleration. Some Independents also wanted to bring an end to the monarchy. Most members of the House of Commons were Presbyterians. These men were willing to share power with the King. Presbyterians also had strong feelings on religion. They disapproved of other puritan groups such as the Anabaptists, Quakers, Levellers, and Congregationalists and wanted them suppressed. (11)

In 1646 Thomas Harrison was elected to Parliament as MP for Wendover. In the same year he married his cousin Catherine Harrison, the daughter of his father's brother Ralph Harrison, a woollen draper in Watling Street, London. Harrison and his wife settled in Highgate and they attended the church at St Ann Blackfriars, which later housed a Fifth Monarchists congregation. Their three children were buried there in 1649, 1652, and 1653. (12)

During the English Civil War a group emerged that was called the Levellers. Members of this group included John Lilburne, Elizabeth Lilburne, Richard Overton, Mary Overton, Thomas Prince, Katherine Chidley, John Wildman and William Walwyn. In September, 1647, Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%. (13)

In October, 1647, the Levellers published An Agreement of the People. As Barbara Bradford Taft has pointed out: "Under 1000 words overall, the substance of the Agreement was common to all Leveller penmen... Inflammatory demands were avoided and the first three articles concerned the redistribution of parliamentary seats, dissolution of the present parliament, and biennial elections. The heart of the Leveller programme was the final article, which enumerated five rights beyond the power of parliament: freedom of religion; freedom from conscription; freedom from questions about conduct during the war unless excepted by parliament; equality before the law; just laws, not destructive to the people's well-being." (14)

Harrison was sympathetic to the demands of the Levellers and in November, 1648, he began negotiating with John Lilburne. "He attempted to persuade the Levellers that before the agreement could be perfected it was necessary for the army to invade London and prevent parliament from concluding a treaty with the king." He argued that any agreement was likely that the New Model Army. would be disbanded, with the consequence "that you will be destroyed as well as we." (15)

Harrison told Lilburne that Major General Henry Ireton and he "were resolved to destroy the King". (16) It was agreed that a joint committee of four parliamentary (political) Independents, four London (religious) Independents, four of the Army leaders and four Levellers should set about drafting a new An Agreement of the People. This included John Lilburne, Henry Marten, William Walwyn and John Wildman. (17)

Lilburne admitted that Harrison was "extremely fair" in the negotiations. "We fully and effectually acquainted

him with the most desperate mischievousness of their attempting to do these things, without giving some good security to the nation for the future settlement of their liberties and freedoms; specially in frequent, free, and successive representations, according to their many promises, oaths, covenants and declarations; or else as soon as they had performed their intentions to destroy the King (which we fully understood they were absolutely resolved to do, yea, as they told us, though they did it by martial law), and also totally to root up the Parliament, and invite so many members to come to them as would join with them, to manage businesses, till a new and equal representative could by an agreement be settled ; which the chiefest of them protested before God was the ultimate and chiefest of their designs and desires... I say, we pressed hard for security, before they attempted those things in the least, lest when they were done we should be solely left to their wills and swords." (18)

Execution of Charles I

Harrison was opposed to negotiations with Charles I and argued "that the king was a man of blood" who ought to be prosecuted for his crimes. Oliver Cromwell agreed with him and in January 1649, Parliament decided to charge Charles with "waging war on Parliament." It was claimed that he had contrived "a wicked design totally to subvert the ancient and fundamental laws and liberties of this nation" and was responsible for "all the murders, burnings, damages and mischiefs to the nation" in the war. The House of Commons passed a resolution that "the people are, under God, the original of all just power" and that they represented the people." (19)

The jury included members of Parliament, army officers and large landowners. Some of the 135 people chosen as jurors did not turn up for the trial. For example. General Thomas Fairfax, the leader of the Parliamentary Army, did not appear. When his name was called, a masked lady believed to be his wife, shouted out, " He has more wit than to be here." This was the first time in English history that a king had been put on trial. Charles believed that he was God's representative on earth and therefore no court of law had any right to pass judgement on him. Charles therefore refused to defend himself against the charges put forward by Parliament.

Charles pointed out that in December 1648, the army had expelled several members of' Parliament. Therefore, Charles argued, Parliament had no legal authority to arrange his trial. The arguments about the courts legal authority to try Charles went on for several days. Eventually, on 27th January, 1649, Charles was given his last opportunity to defend himself against the charges. When he refused he was sentenced to death. (20)

The King's death warrant was signed by the fifty-nine jurors who were in attendance. This included Thomas Harrison. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has argued: "To the sects of the left, the execution of Charles... was a symbolic act of justice, an apocalyptic deed, ushering in the Fifth Monarchy, the rule of the saints... The Levellers, already expressing their political ideas in more secular terms, saw it as the prelude to a more democratic system and perhaps to a social revolution." (21)

The Commonwealth

In May 1649 a Leveller inspired mutiny broke out at Salisbury. Led by Captain William Thompson, they were defeated by a large army at Burford led by Major General Harrison. Thompson escaped only to be killed a few days later near the Diggers community at Wellingborough. After being imprisoned in Burford Church with the other mutineers, three other leaders, "Private Church, Corporal Perkins and Cornett Thompson", were executed by Harrison's forces in the churchyard. (22) John Lilburne responded by describing Harrison as a "hypocrite" for his initial encouragement of the Levellers. (23)

General Thomas Fairfax appointed Thomas Harrison as commander-in-chief of the Commonwealth's forces in the counties of Monmouthshire, Glamorgan, Brecknockshire, Radnorshire, Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire, Herefordshire, and parts of Gloucestershire. In 1650 he was given command of the forces in England during Cromwell's absence in Scotland. In February 1651, he became a member of the Council of State. A few months later Charles II marched into England at the head of a Scottish army. Harrison took part in the battle of Worcester (3rd September) and was given the job of pursuing the fleeing royalists. He completed the assignment so energetically and skilfully that few royalists escaped. (24)

Oliver Cromwell became increasingly frustrated by the inability of Parliament to get anything done. His biographer, Pauline Gregg, has pointed out: "He realized that all revolutions are about power and he was asking himself who, or what, should exercise that power. He knew, moreover, that whoever or whatever was in control must be strong enough to propel the state in one direction. This he learned from his battle experience. To be successful an army must observe one plan, one directive." (25)

Major General Thomas Harrison, who had been sympathetic to the demands of the Levellers, urged the House of Commons to pass legislation to help the poor. In August 1652, he promoted an army petition that called for law reform, the more effective propagation of the gospel, the elimination of tithes, and speedy elections for a new parliament. When it failed to act on these items, Harrison began to press for its dissolution. Harrison argued that when it was established after the death of the Charles I it was "unanimous in its proceedings for the reform of the nation" but it was now dominated by "a strong Royalist party". (26)

On 20th April 1653, Cromwell sent in his troopers with their muskets and drawn swords into the House of Commons. Harrison himself pulled the Speaker, William Lenthall, out of the Chair and pushed him out of the Chamber. That afternoon Cromwell dissolved the Council of State and replaced it with a committee of thirteen army officers. Harrison was appointed as chairman and in effect the head of the English state. (27)

According to Edmund Ludlow, a senior officer in the New Model Army, Harrison was a committed Fifth Monarchists and was willing to take up arms to usher in the kingdom of heaven on earth. Harrison used to quote the apocalyptic book of Daniel (7:18) that "the saints… shall take the kingdom", to which he added another to the same effect, "That the kingdom shall not be left to another people"'. (28)

In July, 1653, Oliver Cromwell established the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints. The total number of nominees was 140 (129 from England, five from Scotland and six from Ireland). Harrison was responsible for nominating four members of his own Fifth Monarchist sect, as well as getting himself elected to the new council of state. (29) The nominated assembly grappled with several of Harrison's favourite issues, including the immediate abolition of tithes. There was general consensus that tithes were objectionable, but no agreement about what mechanism for generating revenue should replace them. (30)

The Parliament was closed down by Cromwell in December, 1653. Charles H. Simpkinson has argued that Harrison now believed that "England now lay under a military despotism". (31) This decision was fiercely opposed by Thomas Harrison. Cromwell reacted by depriving him of his military commission, and in February, 1654, he was ordered to retire to Staffordshire. However, he was able to keep the land he had acquired during his period of power. The total value of this land was well over £13,000. (32)

Harrison was associated with the Levellers and the Anabaptists who were still advocating reform. On 13th September, 1654, Oliver Cromwell made a speech where he "spoke against the Levellers, the Independents, the Anabaptists, making it to appear that the one and the other, under pretence of establishing entire equality, and to persuade the people that the time of the Fifth Monarchy was come, did only labour and intend thereby, the establishment of their own greatness ; and after that he had admonished them of having a care of such men, and that they should not

believe that Christ would come and reign bodily here upon earth, but in the hearts." (33)

In February 1655 an informer told the government that Harrison was involved in a plot against the government. After being placed under house arrest for a few days Harrison was lodged in Portland Castle. In March 1656 he was released and allowed to live at Highgate with his family. Fifth Monarchist agitation continued in 1657, and once again he was placed under arrest, this time in Pendennis Castle. (34)

Execution of Thomas Harrison

Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September, 1658. A few months previously, Cromwell had announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. In May 1659, the generals forced Richard to retire from government. (35)

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army of 8,000 men to London. When Monck arrived he reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. (36)

Monck now began negotiations with Charles II, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an "absolute" monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (37)

On the Restoration Harrison was an obvious target for the Royalists. Harrison refused to flee the country and was therefore like other Regicides arrested and brought to the Tower of London. At his trial in October 1660 he asserted that he had acted in the name of the parliament of England and by their authority. "Maybe I might be a little mistaken, but I did it all according to the best of my understanding, desiring to make the revealed will of God in his holy scriptures as a guide to me". (38)

Harrison claimed he had been acting on the authority of the House of Commons: Denzil Holles rejected this argument. "You do very well know that this that you did, this horrid, detestable act which you committed, could never be perfected by you till you had broken the Parliament. That House of Commons, which you say gave you authority, you know what yourself made of it when you pulled out the speaker; therefore do not make the Parliament to be the author of your black crimes." (39)

Harrison was found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. On 13th October 1660 he was taken on a sledge to Charing Cross, the place of his execution. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (40) Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves." (41)

Samuel Pepys witnessed his execution: "I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison, hanged, drawn, and quartered... he looked as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there were great shouts of joy... Harrison's head has been set up (on a pole) on the other side of Westminster Hall." (42)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles H. Simpkinson, Thomas Harrison: Regicide and Major-General (1905)

Thomas Harrison was after a time sent to London to be clerk to a solicitor in Clifford's Inn, named Thomas Houlker. And here again young Harrison found himself associated with a number of young men who helped to frame his mind to opposition to the King and bishops. In this solicitor's office he remained till the struggle began in 1642 between the King and Parliament. Then he with a number of other young men, who were connected with the law, resolved to take part in the struggle on the Parliamentary side. They offered themselves for exercise in military drill, and were speedily enrolled in the body-guard of the new commander-in-chief, the Earl of Essex, who as a soldier trained in the Dutch wars, was able to inspire the young men of London with keen enthusiasm after the long years of peace...

Harrison was, indeed, a man unlikely to remain unnoticed, since he had the gift of expressing himself with remarkable enthusiasm and eloquence, and when once his opportunity of distinguishing himself came, he was sure to prove that

he understood how to fight as well as to talk. And further, his religious opinions had already taken the shape of a confidence in the direct inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and in the call given to the soldiers to vindicate the authority of Almighty God, by establishing the reign of righteousness in England. These opinions were entirely in harmony with the aspirations of many of the bravest fighters in the ranks of the Eastern Counties Association. Vague and misty

they necessarily were at present; none the less the expression of them stirred high hopes in the hearts of men with whom personal religion was ever the first motive of action.

(2) Thomas Harrison, speech on the scaffold (13th October, 1660)

Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves.

(3) Samuel Pepys, diary entry (13th October, 1660)

I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison, hanged, drawn, and quartered... he looked as cheerful as any man could do in that condition. He was presently cut down, and his head and heart shown to the people, at which there were great shouts of joy... Harrison's head has been set up (on a pole) on the other side of Westminster Hall.

Student Activities

Military Tactics in the English Civil War (Answer Commentary)

Women in the English Civil War (Answer Commentary)