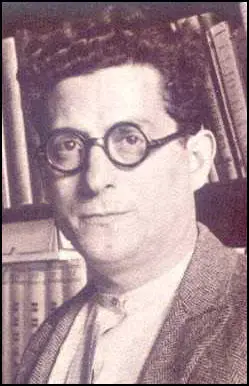

Andres Nin

Andres Nin, the son of a shoemaker, was born in El Vendrell, Tarragona, on 4th February, 1892. He moved to Barcelona in 1914 and during the First World War he taught at a secular anarchist school. In 1917, he joined the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).

Nin helped to form the Communist Party (PCE) in November, 1921. It was made up of dissident members of the Socialist Party, the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT).

In 1931 he wrote in The Militant: "The unusual situation through which our country is passing presents the Communist Left Opposition with gigantic tasks. Although the situation is objectively favorable for the development of Communism and for the preparation of the victory of the proletariat there is the danger that the revolutionary process that has begun may end in a miscarriage that will have fatal consequences not only for the revolutionary movement of our country but for the whole world. Those dangers have their origin in causes of various kinds: in the influence exercized in our movement by anarcho-syndicalism, in the strength that the Socialist party still has in certain points of Spain, and above all in the extreme feebleness of Spanish Communism and the disastrous policy of the International. In reality, there is no Communist party in Spain. There exist various factions that fight each other and lack, with the exception of our own, ideological cohesion. Under these circumstances, the constitution of a powerful Communist party is urgently imposed upon us. But this will be impossible without a clear policy, capable of taking advantage of the inevitable discontentment that will not be long in developing among the broad popular masses of the country, deceived by republicanism, in order to win them to our cause and to lead the proletariat to the conquest of power. It is obvious that this can be achieved only under the banner of the Communist Left Opposition. In spite of the difficulties under which we are fighting, we have already achieved in recent times very satisfactory results. But these would be infinitely greater were we to have the possibility of making our voice heard more directly by the masses."

Nin moved to the Soviet Union and associated with those opposing the dictorial rule of Joseph Stalin. During this period he was briefly secretary to Leon Trotsky. On his return to Spain in 1935 he joined with Joaquin Maurin to form the Workers Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). This revolutionary anti-Stalinist Communist party was strongly influenced by the political ideas of Trotsky. The group supported the collectivization of the means of production and agreed with Trotsky's concept of permanent revolution.

Nin later wrote: "Our party has repeatedly insisted, during these recent times, on the need to provide a political solution to the problems which have arisen during the war and revolution. We even declared that the working class could take power without the need to resort to armed insurrection: it would be enough to bring its enormous influence into play for the relationship of forces to decide in its favour, to achieve a workers’ and peasants’ government without violence of any kind. Failure to confront the problem in these terms, on the political plane, would sooner or later produce a violent explosion, of the accumulated anger of the working class and, as a result, a movement that would be spontaneous, chaotic and lacking in immediate perspectives."

As a result of Maurin's involvement, POUM was very strong in Catalonia. In most areas of Spain it made little impact and in 1935 POUM is estimated to have only around 8,000 members. After the Popular Front gained victory Nin became councillor of justice. He supported the government but his radical policies such as nationalization without compensation, were not introduced. During the Spanish Civil War the Workers Party of Marxist Unification grew rapidly and by the end of 1936 it was 30,000 strong with 10,000 in its own militia.

The American journalist, John Dos Passos, went to interview Nin in 1936: "Nin was well-built and healthy looking and probably looked younger than his age; he had a ready childish laugh that showed a set of solid white teeth. From time to time as we were talking the telephone would ring and he would listen attentively with a serious face. Then he'd answer with a few words too rapid for me to catch and would hang up the receiver with a shrug of the shoulders and come smiling back into the conversation again."

During the Spanish Civil War the Workers Party of Marxist Unification grew rapidly and by the end of 1936 it was 30,000 strong with 10,000 in its own militia. Luis Companys attempted to maintain the unity of the coalition of parties in Barcelona. However, after the Soviet cousul, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, threatened the suspension of Russian aid, he agreed to sack Nin as minister of justice in December 1936. Nin's followers were also removed from the government.

Joseph Stalin appointed Alexander Orlov as the Soviet Politburo adviser to the Popular Front government. Orlov and his NKVD agents had the unofficial task of eliminating the supporters of Leon Trotsky fighting for the Republican Army and the International Brigades. This included the arrest and execution of leaders of the Worker's Party (POUM), National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT) and the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI).

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "Stalin had a secret and extremely important aim in Spain: to eliminate the supporters of Trotsky who had gathered from all over the world to fight for the Spanish revolution. NKVD men, and Comintern agents loyal to Stalin, accused the Trotskyists of espionage and ruthlessly executed them." Orlov later claimed that "the decision to perform an execution abroad, a rather risky affair, was up to Stalin personally. If he ordered it, a so-called mobile brigade was dispatched to carry it out. It was too dangerous to operate through local agents who might deviate later and start to talk."

Alexander Orlov ordered the arrest of Nin. George Orwell explained what happened to Nin in his book, Homage to Catalonia (1938): "On 15 June the police had suddenly arrested Andres Nin in his office, and the same evening had raided the Hotel Falcon and arrested all the people in it, mostly militiamen on leave. The place was converted immediately into a prison, and in a very little while it was filled to the brim with prisoners of all kinds. Next day the P.O.U.M. was declared an illegal organization and all its offices, book-stalls, sanatoria, Red Aid centres and so forth were seized. Meanwhile the police were arresting everyone they could lay hands on who was known to have any connection with the P.O.U.M."

Nin who was tortured for several days. Jesus Hernández, a member of the Communist Party, and Minister of Education in the Popular Front government, later admitted: "Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the dry method. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin resisted the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days his face was a shapeless mass of flesh."

Andres Nin was executed on 20th June 1937.

Primary Sources

(1) Andres Nin, The Militant (8th August 1931)

The unusual situation through which our country is passing presents the Communist Left Opposition with gigantic tasks. Although the situation is objectively favorable for the development of Communism and for the preparation of the victory of the proletariat there is the danger that the revolutionary process that has begun may end in a miscarriage that will have fatal consequences not only for the revolutionary movement of our country but for the whole world. Those dangers have their origin in causes of various kinds: in the influence exercized in our movement by anarcho-syndicalism, in the strength that the Socialist party still has in certain points of Spain, and above all in the extreme feebleness of Spanish Communism and the disastrous policy of the International. In reality, there is no Communist party in Spain. There exist various factions that fight each other and lack, with the exception of our own, ideological cohesion. Under these circumstances, the constitution of a powerful Communist party is urgently imposed upon us. But this will be impossible without a clear policy, capable of taking advantage of the inevitable discontentment that will not be long in developing among the broad popular masses of the country, deceived by republicanism, in order to win them to our cause and to lead the proletariat to the conquest of power. It is obvious that this can be achieved only under the banner of the Communist Left Opposition. In spite of the difficulties under which we are fighting, we have already achieved in recent times very satisfactory results. But these would be infinitely greater were we to have the possibility of making our voice heard more directly by the masses.

(2) John Dos Passos, The Villages Are the Heart of Spain (1937)

The headquarters of the unified Marxist party (P.O.U.M.). It's late at night in a large bare office furnished with odds and ends of old furniture. At a bit battered fake Gothic desk out of somebody's library. Andres Nin sits at the telephone. I sit in a mangy overstuffed armchair. On the settee opposite me sits a man who used to be editor of a radical publishing house in Madrid. We talk in a desultory way with many pauses about old times in Madrid, about the course of the war. They are telling me about the change that has come over the population of Barcelona since the great explosion of revolutionary feeling that followed the attempted military coup d'etat and swept the fascists out of Catalonia in July. "You can even see it in people's dress," said Nin from the telephone laughing. "Now we're beginning to wear collars and ties again but even a couple of months ago everybody was wearing the most extraordinary costumes... you'd see people on the street wearing feathers."

Nin was wellbuilt and healthy looking and probably looked younger than his age; he had a ready childish laugh that showed a set of solid white teeth. From time to time as we were talking the telephone would ring and he would listen attentively with a serious face. Then he'd answer with a few words too rapid for me to catch and would hang up the receiver with a shrug of the shoulders and come smiling back into the conversation again. When he saw that I was begin-ning to frame a question he said, "It's the villages... They want to know what to do." "About Valencia taking over the police services?" He nodded. "What are they going to do?" "Take a car and drive through the suburbs of Barcelona, you'll see that all the villages are barricaded. The committees are all out on the streets with machine guns." Then he laughed. "But maybe you had better not."

"He'd be all right," said the other man. "They have great respect for foreign journalists." "Is it an organized movement?" "It's complicated.... in Bellver our people want to know whether they ought to move against the anarchists. In other places they are with them. You know Spain."

It was time for me to push on. I shook hands with Nin and with a young Englishman who also is dead now, and went out into the rainy night. Since then Nin has been killed and his party suppressed.

(3) Anis Nin, The May Days in Barcelona (May 1937)

Our party has repeatedly insisted, during these recent times, on the need to provide a political solution to the problems which have arisen during the war and revolution. We even declared that the working class could take power without the need to resort to armed insurrection: it would be enough to bring its enormous influence into play for the relationship of forces to decide in its favour, to achieve a workers’ and peasants’ government without violence of any kind. Failure to confront the problem in these terms, on the political plane, would sooner or later produce a violent explosion, of the accumulated anger of the working class and, as a result, a movement that would be spontaneous, chaotic and lacking in immediate perspectives.

Our predictions have been borne out. The provocative attitude of the counter-revolution caused the explosion. But once the workers were in the streets, our party had to adopt a position. Which? To keep out of the movement, to condemn it or to solidarise with it? Our choice was not difficult. Neither the first nor the second attitude squared with our character as a working class and revolutionary party, and without a moment’s hesitation we opted for the third: to offer our active solidarity with the movement, even though we knew in advance that it could not succeed.

If the decision had depended on us, we would not have ordered the insurrection, as the moment was not favourable for a decisive action. But the revolutionary workers, justifiably indignant at the provocation of which they were the victims, threw themselves into battle, and we could not abandon them. To act otherwise would have been an unpardonable betrayal.

We had to do so, not only because we are a revolutionary party, morally obliged to stand by the workers when, rightly or wrongly, they enter into battle in defence of their conquests, but also because of the need to help channel a movement which because of its spontaneity had many chaotic aspects, in order to avoid it being transformed into a fruitless putsch, which would have resulted in a bloody defeat for the proletariat.

(4) George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (1938)

On 15 June the police had suddenly arrested Andres Nin in his office, and the same evening had raided the Hotel Falcon and arrested all the people in it, mostly militiamen on leave. The place was converted immediately into a prison, and in a very little while it was filled to the brim with prisoners of all kinds. Next day the P.O.U.M. was declared an illegal organization and all its offices, book-stalls, sanatoria, Red Aid centres and so forth were seized. Meanwhile the police were arresting everyone they could lay hands on who was known to have any connection with the P.O.U.M.

After his arrest Nin was transferred to Valencia and thence to Madrid, and as early as 21 June the rumour reached Barcelona that he had been shot. Later the rumour took a more definite shape: Nin had been shot in prison by the secret police and his body dumped into the street. This story came from several sources, including Federica Montsenys, an ex-member of the Government. From that day to this Nin has never been heard of alive again.

(5) Jesus Hernandez, The Country of the Big Lie (1973)

Nin was not giving in. He was resisting until he fainted. His inquisitors were getting impatient. They decided to abandon the 'dry' method. Then the blood flowed, the skin peeled off, muscles torn, physical suffering pushed to the limits of human endurance. Nin resisted the cruel pain of the most refined tortures. In a few days his face was a shapeless mass of flesh.

(6) Edward Knoblaugh, Correspondent in Spain (1937)

Juan Negrin, former Minister of Treasury under Largo and a friend of the foreign correspondents, was named Premier to succeed Largo. I had known Negrin for several years and sincerely admired him. Even after the stocky, bespectacled multi-linguist became a cabinet minister he continued his nightly visits to the Miami bar for his after-dinner liqueur. I often chatted with him there, getting angles on the financial situation.

The presence of a moderate Socialist at the head of the new government was a boon to the regime because it strengthened the fiction of a "democratic" government abroad. Largo's ouster, however, produced fresh troubles. Feeling much stronger after its critical first test of strength against the Catalonian Anarcho-Syndicalists, the government had ousted the Anarchist members of the Catalonian Generalitat government and followed this up by excluding the Anarcho-Syndicalists from representation in the new Negrin cabinet.

Largo, it had been thought, would step down gracefully, but, bitterly disappointed and angry, the former Premier immediately began plotting his return to power. The Anarchists, equally bitter at their being deprived of a voice in government, suddenly threw their support to Largo, who adopted as his new campaign slogan the Anarchist cry "We want our social revolution now."

Largo has another important, if less powerful, ally, in the outlawed P.O.U.M. Trotskyites. The disappearance and reported murder of the Trotskyite leader, Andres Nin, added to the bitterness of the P.O.U.M. Nin, one of the foremost revolutionaries in Spain, was arrested last June when the government, at the behest of the Stalin Communists, raided the P.O.U.M. headquarters in Barcelona and arrested many of the members.

It was announced that Nin had been taken first to Valencia and then to Madrid for imprisonment pending trial. When the P.O.U.M., supported by the Anarchists and many of Largo's extreme Socialists, became more and more insistent in their demands that Nin be produced and tried, and the government was unable to dodge the issue any longer, it issued a communiqué to the effect that Nin had "escaped" from the Madrid prison with his guards. Even the Anarchist newspapers were obliged to print this version, but Anarchist and Trotskyite circles were convinced that Nin was murdered enroute to Madrid, and he became a martyr.

Largo regards the present government as bourgeois and counter-revolutionary, and is frankly working for its overthrow. With the opposition to the Negrin government now three-way, neutral observers do not believe that a decisive program can long be avoided. The well-disciplined Communists supporting the Negrin cabinet are confident that if an open fight eventuates, as it seems likely to do either before or after the war, it will have the support of a large percentage of Loyalist Spain. The government will be able to count on its "army within an army." Whether this will be able to cope with the powerful labor unions supporting Largo is problematical.