April Theses

On 10th March, 1917, Tsar Nicholas II had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that the Tsar should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (1)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. Members of the Cabinet included Pavel Milyukov (leader of the Cadet Party), was Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry, and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown." (2)

Prince George Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Joseph Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev and Yakov Sverdlov on 25th March, 1917. The three men had been in exile in Siberia. Stalin's biographer, Robert Service, has commented: "He was pinched-looking after the long train trip and had visibly aged over the four years in exile. Having gone away a young revolutionary, he was coming back a middle-aged political veteran." (3)

The exiles discussed what to do next. The Bolshevik organizations in Petrograd were controlled by a group of young men including Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov who had recently made arrangements for the publication of Pravda, the official Bolshevik newspaper. The young comrades were less than delighted to see these influential new arrivals. Molotov later recalled: "In 1917 Stalin and Kamenev cleverly shoved me off the Pravda editorial team. Without unnecessary fuss, quite delicately." (4)

The Petrograd Soviet recognized the authority of the Provisional Government in return for its willingness to carry out eight measures. This included the full and immediate amnesty for all political prisoners and exiles; freedom of speech, press, assembly, and strikes; the abolition of all class, group and religious restrictions; the election of a Constituent Assembly by universal secret ballot; the substitution of the police by a national militia; democratic elections of officials for municipalities and townships and the retention of the military units that had taken place in the revolution that had overthrown Nicholas II. Soldiers dominated the Soviet. The workers had only one delegate for every thousand, whereas every company of soldiers might have one or even two delegates. Voting during this period showed that only about forty out of a total of 1,500, were Bolsheviks. Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were in the majority in the Soviet.

The Provisional Government accepted most of these demands and introduced the eight-hour day, announced a political amnesty, abolished capital punishment and the exile of political prisoners, instituted trial by jury for all offences, put an end to discrimination based on religious, class or national criteria, created an independent judiciary, separated church and state, and committed itself to full liberty of conscience, the press, worship and association. It also drew up plans for the election of a Constituent Assembly based on adult universal suffrage and announced this would take place in the autumn of 1917. It appeared to be the most progressive government in history. (5)

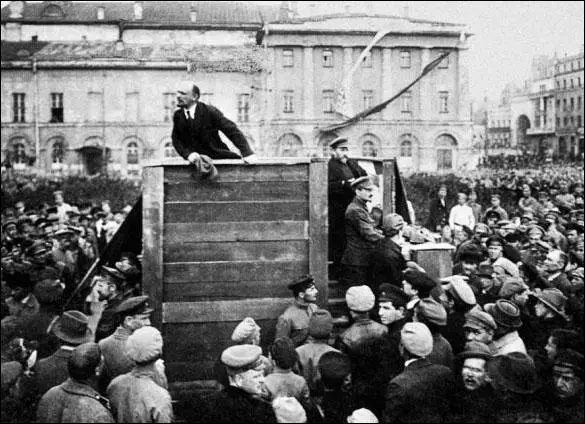

When Lenin returned to Russia on 3rd April, 1917, he announced what became known as the April Theses. As he left the railway station Lenin was lifted on to one of the armoured cars specially provided for the occasions. The atmosphere was electric and enthusiastic. Feodosiya Drabkina, who had been an active revolutionary for many years, was in the crowd and later remarked: "Just think, in the course of only a few days Russia had made the transition from the most brutal and cruel arbitrary rule to the freest country in the world." (6)

In his speech Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Lenin accused those Bolsheviks who were still supporting the government of Prince Georgi Lvov of betraying socialism and suggested that they should leave the party. Lenin ended his speech by telling the assembled crowd that they must "fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the proletariat". (7)

Some of the revolutionaries in the crowd rejected Lenin's ideas. Alexander Bogdanov called out that his speech was the "delusion of a lunatic." Joseph Goldenberg, a former of the Bolshevik Central Committee, denounced the views expressed by Lenin: "Everything we have just heard is a complete repudiation of the entire Social Democratic doctrine, of the whole theory of scientific Marxism. We have just heard a clear and unequivocal declaration for anarchism. Its herald, the heir of Bakunin, is Lenin. Lenin the Marxist, Lenin the leader of our fighting Social Democratic Party, is no more. A new Lenin is born, Lenin the anarchist." (8)

Joseph Stalin was in a difficult position. As one of the editors of Pravda, he was aware that he was being held partly responsible for what Lenin had described as "betraying socialism". Stalin had two main options open to him: he could oppose Lenin and challenge him for the leadership of the party, or he could change his mind about supporting the Provisional Government and remain loyal to Lenin. After ten days of silence, Stalin made his move. In the newspaper he wrote an article dismissing the idea of working with the Provisional Government. He condemned Alexander Kerensky and Victor Chernov as counter-revolutionaries, and urged the peasants to takeover the land for themselves. (9)

Primary Sources

(1) Lenin, April Theses, published in leaflet form on 7th April, 1917.

(1) In our attitude towards the war, which under the new government of Lvov and Co. unquestionably remains on Russia’s part a predatory imperialist war owing to the capitalist nature of that government, not the slightest concession to “revolutionary defencism” is permissible.

The class-conscious proletariat can give its consent to a revolutionary war, which would really justify revolutionary defencism, only on condition: (a) that the power pass to the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants aligned with the proletariat; (b) that all annexations be renounced in deed and not in word; (c) that a complete break be effected in actual fact with all capitalist interests.

In view of the undoubted honesty of those broad sections of the mass believers in revolutionary defencism who accept the war only as a necessity, and not as a means of conquest, in view of the fact that they are being deceived by the bourgeoisie, it is necessary with particular thoroughness, persistence and patience to explain their error to them, to explain the inseparable connection existing between capital and the imperialist war, and to prove that without overthrowing capital it is impossible to end the war by a truly democratic peace, a peace not imposed by violence.

The most widespread campaign for this view must be organised in the army at the front.

(2) The specific feature of the present situation in Russia is that the country is passing from the first stage of the revolution - which, owing to the insufficient class-consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, placed power in the hands of the bourgeoisie - to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest sections of the peasants.

This transition is characterised, on the one hand, by a maximum of legally recognised rights (Russia is now the freest of all the belligerent countries in the world); on the other, by the absence of violence towards the masses, and, finally, by their unreasoning trust in the government of capitalists, those worst enemies of peace and socialism.

This peculiar situation demands of us an ability to adapt ourselves to the special conditions of Party work among unprecedentedly large masses of proletarians who have just awakened to political life.

(3) No support for the Provisional Government; the utter falsity of all its promises should be made clear, particularly of those relating to the renunciation of annexations. Exposure in place of the impermissible, illusion-breeding “demand” that this government, a government of capitalists, should cease to be an imperialist government.

(4) Recognition of the fact that in most of the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies our Party is in a minority, so far a small minority, as against a bloc of all the petty-bourgeois opportunist elements, from the Popular Socialists and the Socialist-Revolutionaries down to the Organising Committee (Chkheidze, Tsereteli, etc.), Steklov, etc., etc., who have yielded to the influence of the bourgeoisie and spread that influence among the proletariat.

The masses must be made to see that the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies are the only possible form of revolutionary government, and that therefore our task is, as long as this government yields to the influence of the bourgeoisie, to present a patient, systematic, and persistent explanation of the errors of their tactics, an explanation especially adapted to the practical needs of the masses.

As long as we are in the minority we carry on the work of criticising and exposing errors and at the same time we preach the necessity of transferring the entire state power to the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies, so that the people may overcome their mistakes by experience.

(5) Not a parliamentary republic - to return to a parliamentary republic from the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies would be a retrograde step - but a republic of Soviets of Workers’, Agricultural Labourers’ and Peasants’ Deputies throughout the country, from top to bottom.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)