Alexander II

Alexander, the eldest son of Tsar Nicholas I, was born in Moscow on 29th April, 1818. Educated by private tutors, he also had to endure rigorous military training that permanently damaged his health.

In 1841 he married Marie Alexandrovna, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt. Alexander became Tsar of Russia on the death of his father in 1855. At the time Russia was involved in the Crimean War and in 1856 signed the Treaty of Paris that brought the conflict to an end.

The Crimean War made Alexander realize that Russia was no longer a great military power. His advisers argued that Russia's serf-based economy could no longer compete with industrialized nations such as Britain and France.

Alexander now began to consider the possibility of bringing an end to serfdom in Russia. The nobility objected to this move but as Alexander told a group of Moscow nobles: "It is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait for the time when it will begin to abolish itself from below".

In 1861 Alexander issued his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments.

Alexander also introduced other reforms and in 1864 he allowed each district to set up a Zemstvo. These were local councils with powers to provide roads, schools and medical services. However, the right to elect members was restricted to the wealthy.

Other reforms introduced by Alexander included improved municipal government (1870) and universal military training (1874). He also encouraged the expansion of industry and the railway network.

Alexander's reforms did not satisfy liberals and radicals who wanted a parliamentary democracy and the freedom of expression that was enjoyed in the United States and most other European states. The reforms in agricultural also disappointed the peasants. In some regions it took peasants nearly 20 years to obtain their land. Many were forced to pay more than the land was worth and others were given inadequate amounts for their needs.

In 1876 a group of reformers established Land and Liberty. As it was illegal to criticize the Russian government, the group had to hold its meetings in secret. Influenced by the ideas of Mikhail Bakunin, the group published literature demanding that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants.

Some reformers favoured a policy of terrorism to obtain reform and on 14th April, 1879, Alexander Soloviev, a former schoolteacher, tried to kill Alexander. His attempt failed and he was executed the following month. So also were sixteen other men suspected of terrorism.

The government responded to the assassination attempt by appointing six military governor-generals that imposed a rigorous system of censorship on Russia. All radical books were banned and known reformers were arrested and imprisoned.

In October, 1879, the Land and Liberty split into two factions. The majority of members, who favoured a policy of terrorism, established the People's Will. Soon afterwards the group decided to assassinate Alexander. The following month Andrei Zhelyabov and Sophia Perovskaya used nitroglycerine to destroy the Tsar train. However, the terrorist miscalculated and it destroyed another train instead. An attempt the blow up the Kamenny Bridge in St. Petersburg as the Tsar was passing over it was also unsuccessful.

The next attempt on Alexander's life involved a carpenter, Stefan Khalturin, who had managed to find work in the Winter Palace. Allowed to sleep on the premises, each day he brought packets of dynamite into his room and concealed it in his bedding.

On 17th February, 1880, Khalturin constructed a mine in the basement of the building under the dinning-room. The mine went off at half-past six at the time that the People's Will had calculated Alexander would be having his dinner. However, his main guest, Prince Alexander of Battenburg, had arrived late and dinner was delayed and the dinning-room was empty. Alexander was unharmed but sixty-seven people were killed or badly wounded by the explosion.

The People's Will contacted the Russian government and claimed they would call off the terror campaign if the Russian people were granted a constitution that provided free elections and an end to censorship. On 25th February, 1880, Alexander announced that he was considering granting the Russian people a constitution. To show his good will a number of political prisoners were released from prison. Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, was given the task of devising a constitution that would satisfy the reformers but at the same time preserve the powers of the autocracy.

At the same time the Russian Police Department established a special section that dealt with internal security. This unit eventually became known as the Okhrana. Under the control of Loris Melikof, the Minister of the Interior, undercover agents began joining political organizations that were campaigning for social reform.

In January, 1881, Loris Melikof presented his plans to Alexander. They included an expansion of the powers of the Zemstvo. Under his plan, each zemstov would also have the power to send delegates to a national assembly called the Gosudarstvenny Soviet that would have the power to initiate legislation. Alexander was concerned that the plan would give too much power to the national assembly and appointed a committee to look at the scheme in more detail.

The People's Will became increasingly angry at the failure of the Russian government to announce details of the new constitution. They therefore began to make plans for another assassination attempt. Those involved in the plot included Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Gesia Gelfman, Nikolai Sablin, Ignatei Grinevitski, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov.

In February, 1881, the Okhrana discovered that their was a plot led by Andrei Zhelyabov to kill Alexander. Zhelyabov was arrested but refused to provide any information on the conspiracy. He confidently told the police that nothing they could do would save the life of the Tsar.

On 13th March, 1881, Alexander was travelling in a closed carriage, from Michaelovsky Palace to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges.

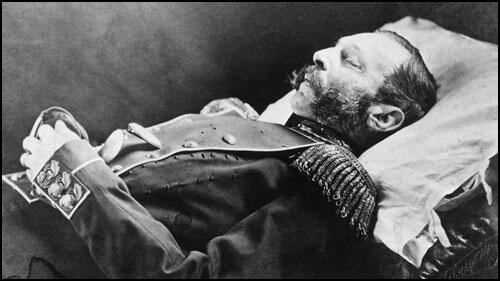

All along the route he was watched by members of the People's Will. On a street corner near the Catherine Canal Sophia Perovskaya gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast.

Of the other conspirators, Nikolai Sablin committed suicide before he could be arrested and Gesia Gelfman died in prison. Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov were hanged on 3rd April, 1881.

Primary Sources

(1) Stephen Graham, Alexander II (1935)

To give the land (to the serfs) meant to ruin the nobility, and to give freedom without land meant to ruin the peasantry. The state treasury impoverished by the vast expenses of war, could not afford to indemnify either party. There lay the problem. Could the serfs made to pay for their freedom? Could the serf-owners be granted loans on the security of their estates? Would not twenty-two million slaves suddenly set free combine to take matters into their own hands.

The position of most large landowners was this. They lived in St. Petersburg or some other great city. They did not farm their estates. They had stewards who administered their property and collected their revenue. They had numbers of serfs paying a handsome annual tribute for their partial freedom, a tribute which the landowners' agents strove incessantly to increase. It was their slaves rather than their land which brought them income.

(2) Victor Serge, From Serfdom to Proletarian Revolution (1930)

From 1840 onwards, the need for serious reform does begin to be apparent: agricultural production is poor, grain exports low, the growth of manufacturing industry slowed down through the shortage of labour; capitalist development is being impeded through aristocracy and serfdom.

It is a perilous situation, which is given a fairly astute solution in the act of "liberation" of 19th February 1861, abolishing serfdom. With a population of sixty-seven million, Russia had twenty-three million serfs belonging to 103,000 landlords. The arable land which the freed peasantry had to rent or buy was valued at about double its real value (342 million roubles instead of 180 million); yesterday's serfs discovered that, in becoming free, they were now hopelessly in debt.

(3) In her memoirs Olga Liubatovich described the reactions of Sophia Perovskaya after the failure to assassinate Alexander II in November, 1879.

A few days after the Moscow explosion, Sophia Perovskaya appeared at one of the party's secret apartments in St. Petersburg. The words began to spill out and she emotionally told us the story of the Moscow attempt. On November 19, it was she who waited in the bushes for the Tsar's train to approach and then gave the signal for the explosion that blew up the tracks. But there had been too little dynamite, she told us; how she regretted that so much had been sent to the operation in the south, instead of concentrating it all in Moscow! There was a catch in her voice as she spoke, and in her face reflected intense suffering; she was shaking, either from a chill produced by her bare wet hands or from a painful feeling of failure and long-suppressed emotion. There was nothing I could do to comfort her.

(4) Stephen Graham, Alexander II (1935)

The Tsar characteristically refused to quit the scene until he had enquired into the condition of the wounded Cossacks. One of them were dead; the others must be removed to hospital and cared for at once. A police officer begged the Tsar to get into his sledge and drive away, but Alexander turned away from him. At that moment another of the gang of assassins hurried up and threw the bomb which blew the Tsar to bits. It was a terrific explosion. Even the Tsar's clothing was torn to rags and his orders and accouterments scattered on the snow. One of his legs were blown away; the other shattered to the top of his thigh. Windows a hundred yards away were broken. The assassin himself was by the same explosion blown to bits.

(5) Vera Figner was involved in the planning of the assassination of Alexander II.

Everything was peaceful as I walked through the streets. But half an hour after I reached the apartment of some friends, a man appeared with the news that two crashes like cannon shots had rung out, that people were saying the sovereign had been killed, and that the oath was already being administered to the heir. I rushed outside. The streets were in turmoil: people were talking about the sovereign, about wounds, death, blood.

On March 3, Kibalchich came to our apartment with the news that Gesia Gelfman's apartment had been discovered, that she'd been arrested and Sabin had shot himself. Within two weeks, we lost Perovskaia, who was arrested on the street. Kibalchich and Frolenko were the next to go. Because of these heavy losses, the Committee proposed that most of us leave St. Petersburg myself included.

(6) Olga Liubatovich was living in St. Petersburg when she heard of the assassination of Alexander II.

One morning I awoke to an unusual commotion in the streets. On every corner, small groups of people were standing around talking about something, shaking their heads. Obviously something important had happened - but what? I went outside. Couriers were tearing madly through the streets. I thought back to the previous evening, March 1, when carriages had been hurrying to the governor's house, which was lit up as for a ball, although there was no sign of a large gathering. Judging from the rumours that were now circulating among the crowd - the sovereign had been killed. Toward noon, the notice of Alexander II's death and Alexander III's accession to the throne appeared, and people started gathering in synagogues and churches to take the oath of allegiance.