The Roman Games

Many Romans believed that when people died their souls were transported by human blood. To help this happen, slaves or prisoners of war were sometimes killed during funerals. When an important Roman citizen called Julius Brutus died in 264 BC, his family had the idea of having three pairs of slaves fight each other during the funeral. In this way blood was shed and the mourners were given some entertainment.

Other prosperous families in Rome copied the example set by the Brutus family. The number of fights that took place at these funerals increased as families attempted to prove that they were richer or more important than other Roman families.

Passers-by often stopped and watched these fights and someone had the idea of putting out seats and charging people who were not friends of the family.

Over the next hundred years the idea of arranging fights between slaves at funerals gradually died out. However, by this time, watching men fight was an important form of entertainment in Rome.

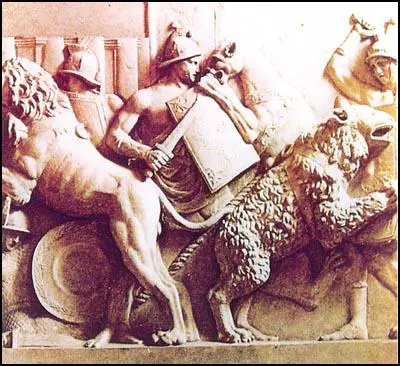

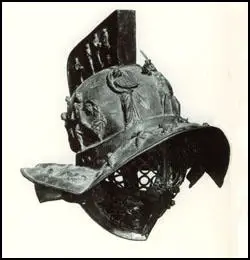

Slaves, called gladiators, were trained in the skills of fighting. At first all the gladiators were made to look like their long-time enemies, the Samnites. They carried a long, rectangular shield, straight sword and helmet. The Romans soon discovered it was more exciting to watch slaves fight with different weapons, and other types of gladiators were introduced.

The front seats were reserved for senators, magistrates and other important officials. Behind them were separate enclosures for patricians and soldiers, followed by another one for the ordinary citizens of Rome. At the top was a gallery for women. The emperor had his own private box with a special staircase that enabled him to enter just before the performance started. When he arrived the whole audience would usually give him a standing ovation. However, when the emperor had recently done something unpopular, the crowd would whistle and sometimes even throw missiles at him.

At the beginning of the games the gladiators would draw lots to find out who they were fighting. The aim of the contest was to kill your opponent. If a gladiator realised he was going to lose he would raise his left arm and point with one finger. The contest would then stop and the emperor or, if he was absent, the president of the games, would ask the crowd to decide whether In 53 BC the first amphitheatre was built. Initially they were made of wood but later giant stadiums of more durable material were constructed. The most famous of these was the Colosseum which seated 50,000 people.

The front seats were reserved for senators, magistrates and other important officials. Behind them were separate enclosures for patricians and soldiers, followed by another one for the ordinary citizens of Rome. At the top was a gallery for women. The emperor had his own private box with a special staircase that enabled him to enter just before the performance started. When he arrived the whole audience would usually give him a standing ovation. However, when the emperor had recently done something unpopular, the crowd would whistle and sometimes even throw missiles at him.

At the beginning of the games the gladiators would draw lots to find out who they were fighting. The aim of the contest was to kill your opponent. If a gladiator realised he was going to lose he would raise his left arm and point with one finger. The contest would then stop and the emperor or, if he was absent, the president of the games, would ask the crowd to decide whether the gladiator should be spared to fight another day. Those who favoured mercy would raise their hands or wave a white handkerchief, while those who wanted to see the man killed would give the thumbs-down sign.

The decision of the crowd would depend on how the defeated gladiator had fought. A man who had shown signs of cowardice or had been a dull fighter would invariably be killed. If the gladiator was a good fighter and had only lost because of bad luck, he might be spared. If the crowd decided the defeated gladiator should die, the emperor or president would turn down his thumb and shout out jugula and the victor would cut the other man's throat.

The Romans liked seeing fights between a retiarius and a mirmillo. The retiarius carried only a long trident and a net. He wore neither helmet or armour and his main objective was to entangle the mirmillo in his net. There were also fights between women slaves, gladiators on horseback, and men in chariots.

It was not only trained gladiators who were killed in the Roman games. Men captured during warfare, who were believed to be too rebellious to become good slaves, were also forced to fight. Some men refused to take part. One group of twenty-nine Saxons committed suicide together rather than fight as gladiators. Another prisoner killed himself by pushing a sponge from the latrines down his throat.

Julius Caesar was one of the first politicians in Rome to realise that providing free gladiatorial contests was a good way of becoming popular with the people. In the early days of his political career, Caesar got himself heavily into debt by putting on free shows. However, by doing so he developed a strong following, and later this was a factor in helping him gain power.

These free shows became known as the Roman Games. Emperors who followed Caesar continued the policy of paying for this entertainment. Over the years the Roman Games grew in size. Emperor Augustus boasted that he could provide an average of 625 pairs of gladiators for every spectacle that he organised. A hundred years later Emperor Trajan put on a show that lasted 123 days and included 9,138 gladiators. The games also took place more often and by AD 350 about 175 days a year were devoted to the games.

In an effort to keep the people of Rome happy, emperors were constantly looking for new ways of making the games more exciting. One of the most popular developments was the staging of famous battles from the past. Employing their aqueduct system and a large basin (538 metres by 360 metres), it was even possible for them to replay naval battles in the amphitheatre. In AD 53 Emperor Claudius staged a naval battle that involved 19,000 men.

Probably the most spectacular innovation was the animal hunt. Exotic animals from all over the empire were brought to Rome to be hunted in the amphitheatre. Trees and bushes were planted in the arena to make the hunt look realistic. The Roman people loved seeing new animals. Caesar caused a

sensation when he first brought back giraffes from his travels.

From safe walkways specially built across the arena, Emperor Commodus, in one morning, killed over a 100 lions and bears. In AD 50 over 5,000 animals, including elephants, tigers, leopards, crocodiles, giraffes, lynxes, rhinoceros and ostriches were killed in one day. Some species of animals were completely destroyed during this period.

In the amphitheatre a rhinoceros would be paired with an elephant, a python with a bear and a lion with a crocodile. To encourage the animals to fight, they were starved for several days before the contest. Even so, like the prisoners, they sometimes refused to fight.

Wild animals were also used to kill prisoners and criminals. It was mainly used as a punishment for those people the Romans particularly hated. For example, soldiers who deserted from the army were killed in this way. On one occasion, there was a shortage of prisoners to be executed, so Emperor Caligula ordered that a group of spectators should be thrown to the wild beasts.

Even after the Romans became converted to Christianity they continued to hold the Roman Games. Some Christian leaders complained about the games and in AD 469 Emperor Anthemius ruled that they should not take place on Sundays. However, it was not until the final stages of the Roman Empire that gladiatorial fights and the killing of wild animals for popular entertainment came to an end.

Primary Sources

(1) Seneca, Moral Epistles (c. AD 60)

The gladiators have nothing to protect them: their bodies are utterly open to every blow: every thrust finds its mark... Most people prefer this kind of thing to all other matches... The sword is not checked by helmet or shield. What good is armour? What good is swordsmanship? All these things only put off death a little. In the morning men are matched with lions and bears, at noon with their spectators... death is the fighters' only exit.

(2) Suetonius, Julius Caesar (c. AD 110)

His public shows were of great variety... Wild-beast hunts took place five days running, and the entertainment ended with a battle between two armies, each consisting of 500 infantry, twenty elephants, and thirty cavalry... Such huge numbers of visitors flocked to these shows from all directions that many of them had to sleep in tents pitched along the streets or roads, or on roof tops; and often the pressure of the crowd crushed people to death.

(3) Cicero, in a letter to a friend described a visit to the games (55 BC)

The wild-beast hunts, two a day for five days were magnificent... But what pleasure can it possibly be to a man of culture, when either a puny human being is mangled by a most powerful beast, or a splendid beast is killed with a hunting spear? The last day was that of the elephants, and on that day the mob and crowd was greatly impressed, but expressed no pleasure. Indeed the result was a certain compassion and a kind of feeling that this huge beast has a fellowship with the human race.

(4) Keith Hopkins, History Today Magazine (June 1983)

Rome was a cruel society... They won their huge empire by discipline and control. Public executions were a gruesome reminder to citizens, subjects and slaves, that vengeance would be exacted if they rebelled or betrayed their country.

(5) Juvenal, Satire X (c. AD 120)

Time was when plebeians elected generals and commanders of legions: but now... there's only two things that concern them: bread and games.

(6) Grave inscription (c. AD 175)

Glauco, born in Mutina, fought seven times, died in the eighth. He lived 23 years and 5 days. Aurelia set this up to her husband.

(7) Graffiti in Pompeii (c. AD 79)

20 pairs of gladiators will fight at Pompeii 8 April... Aemilius painted this, all alone in the moonlight.

(8) Graffiti found in the gladiators' barracks in Pompeii (c. AD 79)

Seneca is the only Roman writer to condemn the bloody Games.

(9) Salvian, On the Governance of God (c. AD 450)

In these (the Roman Games) the greatest pleasure is to have men die, or, what is worse... to have them torn to pieces... to have men eaten, to the great joy and the delight of the onlookers... There are no shows given now in Mayence... nor at Cologne, for they are now controlled by the barbarians... What hope have Christians in the sight of God when these evils only cease to exist... when Roman cities themselves have come under the control of the barbarians.