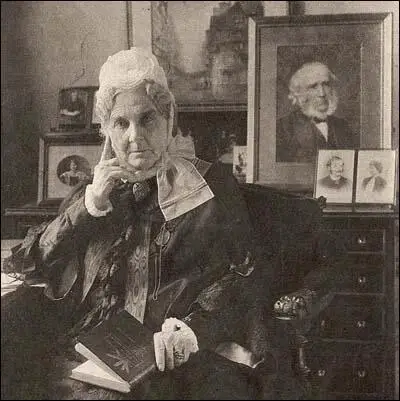

Priscilla McLaren

Priscilla Bright, the fifth in the family of eleven children of Jacob Bright (1775–1851) and his wife, Martha Wood Bright, was born in Rochdale on 8th September 1815. John Bright and Jacob Bright were two of her brothers. (1)

Her father was a self-made and successful cotton manufacturer. He was deeply religious and sent his sons to Quaker schools. This education helped to develop in Bright a passionate commitment to political and religious equality. (2)

Priscilla Bright was educated at Hannah Wilson's school in York, and at Hannah Johnson's school in Liverpool. Her "upbringing gave her a keen and active interest in politics which she never lost until the end of her life". (3)

As a girl she visited Newgate prison with her fellow Quaker, Elizabeth Fry. After John Bright's first wife, Elizabeth, died in September 1841, leaving an eleven-year-old daughter, Priscilla Bright moved into her brother's Rochdale home. Like her brothers she was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party and eventually married, Duncan McLaren, who shared her progressive political beliefs. They had one daughter and two sons. She also took on responsibility for five stepchildren, the eldest of whom was seventeen. (4)

Priscilla McLaren was a supporter of women's suffrage. On 20th May 1867, John Stuart Mill, proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together." (5)

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (6)

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Members included Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. (7) Priscilla McLaren decided to form the Edinburgh Society for Women's Suffrage. (8)

In 1870 Priscilla McLaren joined with her sister-in-law, Ursula Bright, Josephine Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy in forming the Ladies' National Association, an organisation that pressed for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. This legislation allowed policeman to arrest prostitutes in ports and army towns and bring them in to have compulsory checks for venereal disease. If the women were suffering from sexually transmitted diseases they were placed in a locked hospital until cured. It was claimed that this was the best way to protect men from infected women. Many of the women arrested were not prostitutes but they still were forced to go to the police station to undergo a humiliating medical examination. (9)

In 1870 her brother, Jacob Bright and Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke introduced what was the first women's suffrage bill. In one speech he argued: "I know of no reason for the electoral disabilities of women. I know some reasons, which if there are to be electoral disabilities, would lead me to begin elsewhere than with women. Women are less criminal than men: they are more temperate than men the distinction is not small, it is broad and conspicuous; women are less vicious in their habits than men; they are more thrifty, more provident: they give more to the family, and take less to themselves." (10)

After its defeat Jacob Bright introduced another Women's Suffrage Bill in 1871. Once again, William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, arranged for it to be defeated and commented that women voting in elections would be "a practical evil of an intolerable character". (11)

Priscilla McLaren was active in the demands for changes in the law on women's ownership of property. She became increasingly frustrated with male politicians. She told a conference of the Married Women's Property Committee in 1880 that their struggle was "a question of power... they (men) could not bear that the wife should have power". (12)

The Married Women's Property Act was eventually passed in 1882. Under the terms of the act married women had the same rights over their property as unmarried women. This act therefore allowed a married woman to retain ownership of property which she might have received as a gift from a parent. Before the 1882 Married Women's Property Act was passed this property would have automatically have become the property of the husband. (13)

Priscilla McLaren died from pneumonia at home at Newington House, Blacket Avenue, Edinburgh, on 5th November 1906.

Primary Sources

(1) Edward H. Milligan, Priscilla Bright McLaren : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

After John Bright's first wife, Elizabeth, died in September 1841, leaving an eleven-year-old daughter, Priscilla Bright moved into her brother's Rochdale home, One Ash, until he remarried in June 1847. As well as assisting Bright with fund-raising and canvassing, she ran his household and brought up his daughter, to whom she remained very close and with whom as Helen P. Bright Clark - she worked closely in campaigning activities. In 1842 Priscilla met the recently widowed Scottish Presbyterian Duncan McLaren (1800–1886) while he was on a visit to her brother at One Ash. Freed from her domestic responsibilities on Bright's remarriage, she and McLaren were themselves married on 6 July 1848; they had one daughter and two sons, Charles Benjamin Bright McLaren, first Baron Aberconway, and Walter Stowe Bright McLaren. She also took on responsibility for five stepchildren, the eldest of whom was seventeen. They shared the same broad political interests: for both of them, their Liberal convictions veered strongly towards radicalism. Alike in party politics and single-issue agitation, Priscilla McLaren and her husband were equal partners, though they disagreed from time to time on matters of tactics and policy.

(2) Roger Fulford, Votes for Women (1956)

After John Stuart Mill the conspicuous name among the champions of woman's suffrage in the House of Commons was Jacob Bright. He has been inevitably eclipsed by his famous elder brother, and as in private life he was a shade more worldly so in politics he was somewhat more practical. The young Quaker, Jacob Bright, who once slightly shocked John Bright by staying to watch a dance, and even by organizing a picnic party on First Day had perhaps a shrewder understanding of human beings than his more cloistered brother. He gained experience of life through a long term of managing the family mill at Rochdale and, in those days when courage was needed to espouse the women's cause, he spoke with all the incisive forthrightness of a business man who knows his own mind....

Professor G. M. Trevelyan in contrasting the two brothers has pointed out that Jacob Bright had all his brother's fearless and unyielding temper, together with a greater measure of intellectual daring and suppleness. Speaking with all the authority of Member of Parliament for the potent City of Manchester he seemed to bring to these discussions on the franchise something of the thrust and foresight which had brought riches to the area of England which he represented.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)