1932 Presidential Election

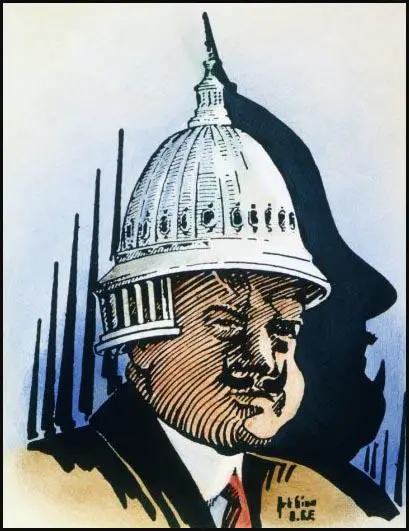

The Wall Street Crash in October 1929, created an economic crisis in America. President Herbert Hoover completely underestimated the importance of the event and argued. "The fundamental business of the country - that is, the production and distribution of goods and services - is on a sound and prosperous basis." (1)

The following month Hoover addressed the nation on how the problem would be solved. "I have... instituted systematic, voluntary measures of cooperation with the business institutions and with State and municipal authorities to make certain that fundamental businesses of the country shall continue as usual, that wages and therefore consuming power shall not be reduced, and that a special effort shall be made to expand construction work in order to assist in equalizing other deficits in employment."

Hoover then went on to claim: "I am convinced that through these measures we have reestablished confidence. Wages should remain stable. A very large degree of industrial unemployment and suffering which would otherwise have occurred has been prevented. Agricultural prices have reflected the returning confidence. The measures taken must be vigorously pursued until normal conditions are restored." (2)

These measures did not work. Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable." (3)

Smoot-Hawley Tariff

President Hoover made the situation worse by the passing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in March 1930. This raised taxes on more than 20,000 imported goods to record levels. In an attempt to persuade Hoover to veto the legislation, 1,028 American economists, including Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, who was considered the most important economist of the period, published a open letter on the subject. (4)

"We are convinced that increased protective duties would be a mistake. They would operate, in general, to increase the prices which domestic consumers would have to pay. By raising prices they would encourage concerns with higher costs to undertake production, thus compelling the consumer to subsidize waste and inefficiency in industry. At the same time they would force him to pay higher rates of profit to established firms which enjoyed lower production costs. A higher level of protection, such as is contemplated by both the House and Senate bills, would therefore raise the cost of living and injure the great majority of our citizens."

The letter went on to point out that since the Wall Street Crash had resulted in much higher-rates of unemployment: "America is now facing the problem of unemployment. Her labor can find work only if her factories can sell their products. Higher tariffs would not promote such sales. We can not increase employment by restricting trade. American industry, in the present crisis, might well be spared the burden of adjusting itself to new schedules of protective duties. Finally, we would urge our Government to consider the bitterness which a policy of higher tariffs would inevitably inject into our international relations. The United States was ably represented at the World Economic Conference which was held under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1927. This conference adopted a resolution announcing that 'the time has come to put an end to the increase in tariffs and move in the opposite direction.' The higher duties proposed in our pending legislation violate the spirit of this agreement and plainly invite other nations to compete with us in raising further barriers to trade. A tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace." (5)

Henry Ford spent an evening at the White House trying to convince Hoover to veto the bill, calling it "an economic stupidity." Thomas W. Lamont, the chief executive of J. P. Morgan Investment Bank said he "almost went down on his knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot tariff." He warned that the act would intensify "nationalism all over the world.” (6)

President Hoover considered the bill "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious" but according to his biographer, Charles Rappleye, "the president could hardly turn its back on a measure endorsed by a clear majority of his own party." (7) Hoover signed the bill on 17th June, 1930. The Economist Magazine argued that the passing of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was "the tragic-comic finale to one of the most amazing chapters in world tariff history… one that Protectionist enthusiasts the world over would do well to study.” (8)

Andrew Mellon was Hoover's secretary of the treasury. Mellon followed policies that involved cutting income tax rates and reducing public spending. He also brought an end to the excess profits tax. Mellon's policies created a great deal of controversy and he was accused of following policies that favoured the wealthy. The economic depression that began in 1929 was partly blamed on Mellon's policies. (9)

Franklin Roosevelt, Governor of New York

Franklin Roosevelt, the Governor of New York, had opposed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. He also disagreed with Hoover when he vetoed a bill that would have created a federal unemployment agency. Hoover also opposed a plan to create a public works programme. In March, 1930, Roosevelt established a commission to stabilize employment in New York. "The situation is serious and the time has come for us to face this unpleasant fact dispassionately". (10)

Unemployment which stood at 4 million in March 1930, reached 8 million in March 1931. Hoovervilles, settlements on tin shacks, abandoned cars and discarded packing crates, emerged on the edges of all big cities. President Hoover responded by urging Americans to embrace the principles of local responsibility and mutual self-help, by setting up community soup kitchens. If we depart from these principles, he argued, we will "have struck at the roots of self-government". (11)

Roosevelt made it clear that he disapproved of this approach to unemployment. He pointed out he was willing to spend $20 million to provide useful work where possible and, where such work could not be found, to provide the needy with food and shelter. "In broad terms I assert that modern society, acting through its government, owes the definite obligation to prevent the starvation or dire want of any of its fellow men and women who try to maintain themselves but cannot... To these unfortunate citizens aid must be extended by government - not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty." (12)

In addition to the $20 million relief package, Roosevelt asked the New York legislature, for funds to establish a new state agency, the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), to distribute the funds. He also requested that the legislature to raise personal income taxes by 50% to pay for the relief effort. New York was the first state to establish a relief agency, and TERA immediately became a model for other states. This included New Jersey, Rhode Island and Illinois. (13)

Roosevelt selected Jesse Straus, president of R. H. Macy department stores, and one of the most respected businessmen in New York, to head TERA. He chose as his executive director a forty-two-year-old social worker, Harry L. Hopkins, who at that time was unknown to Roosevelt or any of his advisers. Hopkins was an inspired choice. A gifted administrator who proved he could deliver aid swiftly. In the next six years TERA assisted some 5 million people - 40 per cent of the population of New York State. (14)

Eleanor Roosevelt pointed out that TERA was the first of her husband's important projects. "Many experiments that were later to be incorporated into a national program were being tried out in the state. It was part of Franklin's political philosophy that the great benefit to be derived from having forty-eight states was the possibility of experimenting on a small scale to see how a program worked before trying it out nationally." (15)

Senior members of the Democratic Party began to talk of Roosevelt being the best man to take on Herbert Hoover in the 1932 Presidential Election. This included Burton Wheeler of Montana, Cordell Hull of Tennessee, James F. Byrnes of South Carolina and Pat Harrison of Mississippi. Roosevelt wrote to his friend, James Hoey, that "the great majority of States through their regular organizations are showing every friendliness towards me." (16)

The Republican Party feared Roosevelt and began circulating unfounded gossip concerning his condition. Time Magazine reported that Roosevelt might be mentally qualified for the presidency, he was "utterly unfit physically". (17) Roosevelt was very concerned about this campaign and wrote to a friend in the media: "I find that there is a deliberate attempt to create the impression that my health is such as would make it impossible for me to fulfill the duties of President... I shall appreciate whatever my friends may have to say in their personal correspondence to dispel this perfectly silly piece of propaganda." (18)

Earle Looker, a journalist who was a supporter of the Republican Party, challenged Roosevelt to undergo a medical examination to prove "you are sufficiently recovered to assure your supporters that you could stand the strain of the Presidency." Roosevelt accepted the challenge immediately. Dr. Lindsay R. Williams, director of the New York Academy of Medicine, was asked to select a panel of eminent physicians, including a brain specialist, to conduct the examination. In addition, Looker was invited to visit Roosevelt unannounced and observe the governor whenever he wished and as often as he wished. (19)

The panel examined Roosevelt on 29th April, 1931, and published its report the same day: "We have today carefully examined Governor Roosevelt. We believe that his health and powers of endurance are such as to allow him to meet any demand of private and public life. We find that his organs and functions are sound in all respects. There is no anemia. The chest is exceptionally well developed, and the spinal column is absolutely normal; all its segments are in perfect alignment and free from disease. He has neither pain nor ache at any time... Governor Roosevelt can walk all necessary distances and can maintain a standing position without fatigue." (20)

Earle Looker took advantage of Roosevelt's offer to visit him at work. Later he recalled: "I observed him working and resting. I noted the alertness of his movements, the sparkle of his eyes, the vigor of his gestures. I saw his strength under the strain of long working periods. Insofar as I observed him, I came to the conclusion that he seemed able to take more punishment than many men ten years younger. Merely his knees were not much good to him... From my own observation I am able to say unhesitatingly that every rumour of Franklin Roosevelt's physical incapacity can be unqualified defined as false." (21)

Democratic Convention

In March 1932 Roosevelt asked Raymond Moley, a professor of public law at Columbia University, "to pull together some intellectuals who might help Roosevelt's bid for the presidency". Moley recruited two of his university colleagues, Rexford G. Tugwell and Adolf Berle. Others who joined the group, later known as the Brains Trust, included Roosevelt's law-partner, Basil O'Connor and his main speech writer, Samuel Rosenman. Felix Frankfurter, Louis Brandeis (who introduced the group to the ideas of John Maynard Keynes) and Benjamin Cohen also attended meetings. (22)

In a speech jointly written by Roosevelt, Moley and Rosenman, he gave a speech on 7th April 1932 where he attacked the Hoover administration for attacking the symptoms of the Great Depression, not the cause. "It has sought temporary relief from the top down rather than permanent relief from the bottom up. These unhappy times call for the building of plans that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid." (23)

Roosevelt constantly made the point that to solve the country's economic problems, the president had to resort to "imaginative and purposeful planning". In a speech at Oglethorpe University he suggested that if he became president he would not be afraid to experiment: "Must the country remain hungry and jobless while raw materials stand unused and factories idle? The country needs, the country demands, bold, persistent experimentation. Take a method and try it. If it fails admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something." (24)

At the convention held to select the presidential candidate a debate took place over the Democratic Party's policy on Prohibition. There appeared to be more concerned about prohibition than over unemployment. John Dewey commented: "Here we are in the midst of the greatest crisis since the Civil War and the only thing the two national parties seem to want to debate is booze." (25)

Prohibition was a problem for Roosevelt as much of his support came from traditionally dry areas in the South and West whereas most party members and the general public favoured repeal. Roosevelt told his supporters to "vote as you wish" and that he would be happy to run on whatever platform the convention adopted. They voted for repeal 934-213. Arthur Krock reported that "the Democratic party went as wet as the seven seas". (26)

The first ballot showed Roosevelt with 666 votes - more than three times as many as his nearest rival but 104 short of victory. Al Smith ran second with 201. At the second ballot Roosevelt's total crept up to 677. The conservative establishment in the South, disliked the radicalism of Roosevelt and made a move, led by Sennet Conner of Mississippi, to select Newton D. Baker as a compromise candidate. Huey Long, the progressive Governor of Louisiana, went to see Conner and said that unless he supported Roosevelt "I'll go into Mississippi and break you." (27)

Roosevelt won the nomination on the fourth ballot when he won 945 votes. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963) summed up the situation that the Democratic Party found itself in: "Liberal Democrats were somewhat uneasy about Roosevelt's reputation as a trimmer, and disturbed by the vagueness of his formulas for recovery, but no other serious candidate had such good claims on progressive support. as governor of New York, he had created the first comprehensive system of unemployment relief, sponsored an extensive program for industrial welfare, and won western progressives by expanding the work Al Smith had begun in conservation and public power." (28)

In his acceptance speech Roosevelt argued: "Yes, the people of this country want a genuine choice this year, not a choice between two names for the same reactionary doctrine. Ours must be a party of liberal thought, of planned action, of enlightened international outlook, and of the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens.... Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage. This is more than a political campaign; it is a call to arms. Give me your help, not to win votes alone, but to win in this crusade to restore America to its own people." (29)

Henry L. Mencken, was a journalist who had great doubts about the wisdom of selecting Roosevelt. He wrote in The Baltimore Evening Sun: "Mr. Roosevelt enters the campaign with a burden on each shoulder. The first is the burden of his own limitations. He is one of the most charming of men, but like many very charming man he leaves on the beholder the impression that he is also somewhat shallow and futile. The burden on his other shoulder is even heavier. It is the burden of party disharmony." (30)

Elmer Davis, in Harper's Magazine, claimed that the Democratic Party had nominated "the man who would probably make the weakest President of the dozen aspirants". (31) Another journalist, Charles Willis Thompson, believed that the Democrats have nominated nobody quite like him since Franklin Pierce." It was pointed out that when Roosevelt was nominated bookies made him a 5-1 chance of beating Herbert Hoover. (32)

The Roosevelt and Hoover Campaigns

Roosevelt's campaign did little to reassure critics who thought him a vacillating politician. For example, he attacked the Hoover administration because it was "committed to the idea that we ought to centre control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible" but advanced policies which would greatly extend the power of the national government. He said he would initiate a far-reaching plan to help the farmer; but he would do it in such a way that it would not "cost the Government any money". (33)

In one speech he made in Sioux City, Roosevelt argued that he would cut government spending by 25 per cent: "I accuse the present Administration of being the greatest spending Administration in peace times in all our history. It is an Administration that has piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission, and has failed to anticipate the dire and the reduced earning power of the people." (34) One of Roosevelt's supporters, Marriner Eccles, admitted: "Given later developments, the campaign speeches often read like a giant misprint, in which Roosevelt and Hoover speak each other's lines." (35)

Huey P. Long, the progressive governor of Louisiana, telephoned Roosevelt to complain about his apparent move to the right. Roosevelt placated Long as best he could because he did not want to lose his support. Roosevelt told one of his advisers that he was unwilling to use the Long approach to politics: "Huey's a whiz on the radio. He screams at people and they love it. He makes them think they belong to some kind of church. He knows there is a promised land and he'll lead them to it." (36)

However, Roosevelt made good use of Long's talents. James Farley, who managed Roosevelt's campaign, later regretted not making more of Long: "We underrated Long's ability to grip the masses. He put on a great show and everywhere he went we got the most glowing reports of what he had accomplished for the Democratic cause... If we had sent Huey into the thickly populated cities of the Pennsylvania mining districts, the electoral vote of the Keystone State would have gone to the Roosevelt-Garner ticket by a comfortable margin." (37)

There was a general agreement that Hoover ran a very bad campaign. Several leading Republican politicians, on the left of the party, including Robert LaFollette Jr of Wisconsin, Hiram Johnson of California, George Norris of Nebraska, Bronson Cutting of New Mexico and Smith Wildman Brookhart of Iowa, supported Roosevelt. Jonathan Bourne of Oregon stated: "I think Hoover is the most pitiful failure we have ever had in the White House." (38)

William E. Leuchtenburg pointed out: "If Roosevelt's program lacked substance, his blithe spirit - his infectious smile, his warm, mellow voice, his obvious ease with crowds - contrasted sharply with Hoover's glumness. While Roosevelt reflected the joy of a campaigner winging to victory. Hoover projected defeat. From the onset of the depression, he had approached problems with a relentless pessimism... A man of impressive accomplishments, he had little understanding of the nuances of the art of governing." (39)

The Bonus Army

During the campaign President Herbert Hoover had to deal with the problems of the Bonus Army. In May 1924 Congress voted $3,500,000,000 to the American veterans of the First World War. President Calvin Coolidge vetoed the bill saying: "patriotism... bought and paid for is not patriotism." However, Congress overrode his veto a few days later, enacting the World War Adjusted Compensation Act. Each veteran was to receive a dollar for each day of domestic service, up to a maximum of $500, and $1.25 for each day of overseas service, up to a maximum of $625. (40)

In order to prevent an immediate strain on its funds, the Government decided to pay the money over a 20 year period. During the Great Depression, many of these veterans found it difficult to find work. An increasing number came to the conclusion that the money would be more useful to them in this time of need than when the bonus was due. As Jim Sheridan pointed out: "The soldiers were walking the streets, the fellas who had fought for democracy in Germany. They thought they should get the bonus right then and there because they needed the money." (41)

In 1932 John Patman of Texas, introduced the Veteran's Bonus Bill which mandated the immediate cash payment of the endowment promised to the men who fought in the war. Although there was congressional support for the immediate redemption of the military service certificates, President Hoover opposed such action claiming that the government would have to increase taxes to cover the costs of the payout. (42)

In a letter to Reed Smoot, the senator from Utah, Hoover explained: "The proposal is to authorize loans upon these certificates up to 50% of their face value. As the face value is about $3,423,000,000, loans at 50% thus create a potential liability for the Government of about $1,172,000,000, and, less the loans made under the original Act, the total cash which might be required to be raised by the Treasury is about $1,280,000,000 if all should apply. The Administrator of Veterans' Affairs informs me by the attached letter that he estimates that if present conditions continue, then 75% of the veterans may be expected to claim the loans, or a sum of approximately $1,000,000,000 will need to be raised by the Treasury." (43)

In May 1932, 10,000 of these ex-soldiers marched on Washington in an attempt to persuade Congress to pass the Patman Bill. When they arrived in the capital the Bonus Army camped at Anacostia Flats, an area that had formerly been used as an army recruiting centre. They built temporary homes on the site and threatened to stay there until they received payment of money granted to them by Congress. It was clear that the veteran camp was a source of great embarrassment to Hoover and provided further proof of the government's callous unconcern for the plight of the people." (44)

John Dos Passos interviewed some of the men and reported on the issue for the The New Republic : "They... needed their bonus now; 1945 would be too late, only buy wreaths for their tombstones. They figured out, too, that the bonus paid now would tend to liven up business, particularly the retail business in small towns; might be just enough to tide them over till things picked up." Unable to afford the travel costs they hitchhiked and rode free on freight trains so they could go to Washington. (45)

Malcolm Cowley pointed out: "They arrived by hundreds or thousands every day in June. Ten thousand were camped on marshy ground across the Anacostia River, and ten thousand others occupied a number of half-demolished buildings between the Capitol and the White House. They organized themselves by states and companies and chose a commander named Walter W. Waters, an ex-sergeant from Portland. Oregon, who promptly acquired an aide-de-camp and a pair of highly polished leather puttees. Meanwhile the veterans were listening to speakers of all political complexions, as the Russian soldiers had done in 1917. Many radicals and some conservatives thought that the Bonus Army was creating a revolutionary situation of an almost classical type." (46)

It is estimated that by June 1932, there were 20,000 men living in the camp. President Herbert Hoover refused to meet with the leaders of the Bonus Army and ordered the gates of the White House chained shut. Police Chief Pelham Glassford did his utmost to provide tents and bedding for the veterans, furnished medicine, and assisted with food and sanitation. "The men were camped illegally, but Glassford (who had been the youngest brigadier general with the AEF in France) choose to treat them simply as old soldiers who had fallen on old times who had fallen on hard times. He resisted efforts to use force to dislodge them." (47)

On 15th June the House of Representatives passed the Bonus Bill by 209-176. Two days later the Senate defeated it 62-18. The veterans were now ordered to leave the city. According to the authorities some 5,000 people did leave the camp. Hoover claimed that "an examination of a large number of names discloses the fact that a considerable part of those remaining are not veterans; many are communists and persons with criminal records." (48)

The vast majority of the people in the camp refused to move. Secretary of War, Patrick J. Hurley, told Hoover that the country faced the possibility of a Communist uprising of vast proportions and talked about the need to impose martial law. The District of Columbia commissioners, on the suggestion of President Hoover, ordered Glassford to clear the area where the veterans were squatting. More controversially, he also instructed the armed forces to become involved in this action. (49)

On 28th July, General Douglas MacArthur and assisted by Major George S. Patton, used soldiers from the 3rd Cavalry Regiment and the 16th Infantry, supported by tanks and machine guns, to clear the area. After a tear gas barrage the cavalry swept the camp, followed by infantrymen, who systematically set fire to the veterans' tents and temporary buildings to stop the men returning. MacArthur, controversially used tanks, four troops of cavalry with drawn sabers, and infantry with fixed bayonets, on the ex-serviceman. He justified his attack by claiming the "mob" was animated by the "essence of revolution". (50)

William E. Leuchtenburg has argued: "Far from being a menacing band of revolutionaries, the Bonus Army was a whipped, melancholy group of men trying to hold themselves together with their spirit was gone. The Communist faction had to be protected from other bonus marchers who threatened physical violence." (51) Irving Bernstein has admitted that there were some criminals in the group, but the record for serious crime in the government of President Harding was proportionately higher than in the Bonus Army. (52)

During the operation two of the men, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, were killed. Time Magazine reported that: "When war came in 1917 William Hushka, 22-year-old Lithuanian, sold his St. Louis butcher shop, gave the proceeds to his wife, joined the Army. He was sent to Camp Funston, Kansas where he was naturalized. Honorably discharged in 1919, he drifted to Chicago, worked as a butcher, seemed unable to hold a steady job. His wife divorced him, kept his small daughter. Long jobless, in June he joined a band of veterans marching to Washington to fuse with the Bonus Expeditionary Force. 'I might as well starve there as here', he told his brother. He took part in the demonstration at the Capital the day Congress adjourned without voting immediate cashing of the bonus. Last week William Hushka's Bonus for $528 suddenly became payable in full when a police bullet drilled him dead in the worst public disorder the capital has known in years." (53)

President Hoover released a statement explaining his actions against the Bonus Army: "For some days police authorities and Treasury officials have been endeavoring to persuade the so-called bonus marchers to evacuate certain buildings which they were occupying without permission... This morning the occupants of these buildings were notified to evacuate and at the request of the police did evacuate the buildings concerned. Thereafter, however, several thousand men from different camps marched in and attacked the police with brickbats and otherwise injured several policemen, one probably fatally... An examination of a large number of names discloses the fact that a considerable part of those remaining are not veterans; many are communists and persons with criminal records." (54)

Some newspapers praised President Hoover for acting decisively, however, most were highly critical of what he had done. The The New York Times, devoted its first three pages to the coverage, including a full page of photographs showing the veterans being attacked. The Washington Daily News stated: "The mightiest government in the world chasing unarmed men, women and children with Army tanks. If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America. (55)

Roosevelt was highly critical of the way President Hoover treated the Bonus Army. He was especially harsh on General Douglas MacArthur who he believed "has prevented Hoover's reelection". He told Rexford Tugwell that MacArthur was the most dangerous person in America. "You saw the picture of him in the New York Times after the troops chased all those vets out with tear gas and burned their shelters. Did you ever see anyone more self-satisfied? There's a potential Mussolini for you. Right here at home." (56)

Final Campaign Speeches

Franklin D. Roosevelt made twenty-seven major addresses during the six month campaign, each devoted to a single subject. He spoke briefly on thirty-two additional occasions, usually at whistle-stops or impromptu gatherings to which he was invited. Herbert Hoover, by contrast, made only ten speeches, all of which were delivered during the closing weeks of the campaign. (57)

At a meeting in Detroit, President Hoover told the audience, "I wish to present to you the evidence that the measures and the policies of the Republican administration are winning this major battle for recovery. And we are taking care of distress in the meantime. It can be demonstrated that the tide has turned and the gigantic forces of depression are today in retreat." (58) The crowd responded with the cry: "Down with Hoover, slayer of veterans". According to one observer: "When he got up to speak, his face was ashen, his hands trembled. Toward the end, Hoover was a pathetic figure, a weary, beaten man, often jeered by crowds as a President had never been jeered before." (59)

The British film-star, Charlie Chaplin, took a keen interest in the election and later commented: "The lugubrious Hoover sat and sulked, because his disastrous economic sophistry of allocating money at the top in the belief that it would percolate down to the common people had failed. And amidst all this tragedy he ranted in the election campaign that if Franklin Roosevelt got into office the very foundations of the American system - not an infallible system at that moment - would be imperilled." (60)

On 31st October, 1932, in a speech in New York City Hoover attempted to show the American public had a clear choice in the election: "This campaign is more than a contest between two men. It is more than a contest between two parties. It is a contest between two philosophies of government. We are told by the opposition that we must have a change, that we must have a new deal.... This question is the basis upon which our opponents are appealing to the people in their fear and their distress. They are proposing changes and so-called new deals which would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life."

Hoover went on to argue: "The proposals of our opponents will endanger or destroy our system. I especially emphasize that promise to promote 'employment for all surplus labour at all times.' At first I could not believe that anyone would be so cruel as to hold out hope so absolutely impossible of realization to these 10,000,000 who are unemployed. And I protest against such frivolous promises being held out to a suffering people. If it were possible to give this employment to 10,000,000 people by the Government, it would cost upwards of $9,000,000,000 a year. It would pull down the employment of those who are still at work by the high taxes and the demoralization of credit upon which their employment is dependent. It would mean the growth of a fearful bureaucracy which, once established, could never be dislodged." (61)

Roosevelt heard Hoover's speech on the radio before appearing in Boston that night: "Once more he warned the people against changing - against a new deal - stating that it would mean changing the fundamental principles of America, what he called the sound principles that have been so long believed in in this country. My friends, my New Deal does not aim to change those principles. Secure in their undying belief in their great tradition and in the sanctity of a free ballot, the people of this country - the employed, the partially employed and the unemployed, those who are fortunate enough to retain some of the means of economic well-being, and those from whom these cruel conditions have taken everything - have stood with patience and fortitude in the face of adversity."

Roosevelt highlighted the plight of the unemployed: "There they stand. And they stand peacefully, even when they stand in the breadline. Their complaints are not mingled with threats. They are willing to listen to reason at all times. Throughout this great crisis the stricken army of the unemployed has been patient, law-abiding, orderly, because it is hopeful. But, the party that claims as its guiding tradition the patient and generous spirit of the immortal Abraham Lincoln, when confronted by an opposition which has given to this Nation an orderly and constructive campaign for the past four months, has descended to an outpouring of misstatements, threats and intimidation. The Administration attempts to undermine reason through fear by telling us that the world will come to an end on November 8th if it is not returned to power for four years more. Once more it is a leadership that is bankrupt, not only in ideals but in ideas." (62)

During the campaign Herbert Hoover had to have a heavy police escort to protect him from the angry crowds. He became very unpopular when he told one of the most influential journalists in Washington, Raymond Clapper: "Nobody is actually starving. The hobos, for example, are better fed than they have ever been." In another interview he attributed the high unemployment rate to the fact that "many people have left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples." (63)

Three days before the election he claimed that Roosevelt's policies could be compared to those of Joseph Stalin. He suggested that his opponent had "the same philosophy of government which has poisoned all of Europe... the fumes of the witch's cauldron which boiled in Russia." He accused the Democrats of being "the party of the mob". Hoover then added: "Thank God, we still have a government in Washington that knows how to deal with the mob." (64)

The turnout, almost 40 million, was the largest in American history. Roosevelt received 22,825,016 votes to Hoover's 15,758,397. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six. Hoover received 6 million fewer votes than he had in 1928. The Democrats gained ninety seats in the House of Representatives to give them a large majority (310-117) and won control of the Senate (60-36). Only one previous Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, had done as badly as Hoover. (65)

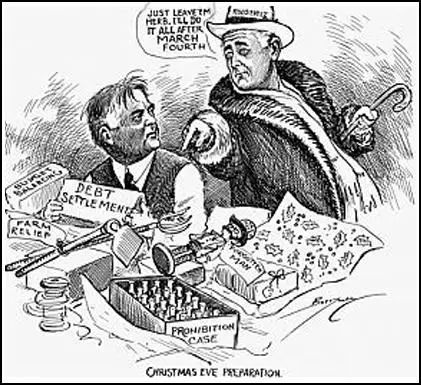

all after March 4th." Cliff Berryman, Washington Evening Star (December, 1932)

Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected on 8th November, 1932, but the inauguration was not until 4th March, 1933. While he waited to take power, the economic situation became worse. Three years of depression had cut national income in half. Five thousand bank failures had wiped out 9 million savings accounts. By the end of 1932, 15 million workers, one out of every three, had lost their jobs. When the Soviet Union's trade office in New York issued a call for 6,000 skilled workers to go to Russia, more than 100,000 applied. (66)

Edmund Wilson published an article in The New Republic just before Roosevelt took office: "There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer, the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps... a widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen-year-old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots." (67)

Primary Sources

(1) Franklin D. Roosevelt, speech on NBC's Lucky Strike Hour radio programme (7th April, 1932)

Although I understand that I am talking under the auspices of the Democratic National Committee, I do not want to limit myself to politics. I do not want to feel that I am addressing an audience of Democrats or that I speak merely as a Democrat myself. The present condition of our national affairs is to serious to be viewed through partisan eyes for partisan purposes.

Fifteen years ago my public duty called me to an active part in a great national emergency, the World War. Success then was due to a leadership whose vision carried beyond the timorous and futile gesture of sending a tiny army of 150,000 trained soldiers and the regular navy to the aid of our allies. The generalship of that moment conceived of a whole Nation mobilized for war, economic, industrial, social and military resources gathered into a vast unit capable of and actually in the process of throwing into the scales ten million men equipped with physical needs and sustained by the realization that behind them were the united efforts of 110,000,000 human beings. It was a great plan because it was built from bottom to top and not from top to bottom.

In my calm judgment, the Nation faces today a more grave emergency than in 1917.

It is said that Napoleon lost the battle of Waterloo because he forgot his infantry — he staked too much upon the more spectacular but less substantial cavalry. The present administration in Washington provides a close parallel. It has either forgotten or it does not want to remember the infantry of our economic army.

These unhappy times call for the building of plans that rest upon the forgotten, the unorganized but the indispensable units of economic power for plans like those of 1917 that build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.

Obviously, these few minutes tonight permit no opportunity to lay down the ten or a dozen closely related objectives of a plan to meet our present emergency, but I can draw a few essentials, a beginning in fact, of a planned program.

It is the habit of the unthinking to turn in times like this to the illusions of economic magic. People suggest that a huge expenditure of public funds by the Federal Government and by State and local governments will completely solve the unemployment problem. But it is clear that even if we could raise many billions of dollars and find definitely useful public works to spend these billions on, even all that money would not give employment to the seven million or ten million people who are out of work. Let us admit frankly that it would be only a stopgap. A real economic cure must go to the killing of the bacteria in the system rather than to the treatment of external symptoms.

How much do the shallow thinkers realize, for example, that approximately one-half of our whole population, fifty or sixty million people, earn their living by farming or in small towns whose existence immediately depends on farms. They have today lost their purchasing power. Why? They are receiving for farm products less than the cost to them of growing these farm products. The result of this loss of purchasing power is that many other millions of people engaged in industry in the cities cannot sell industrial products to the farming half of the Nation. This brings home to every city worker that his own employment is directly tied up with the farmer's dollar. No Nation can long endure half bankrupt. Main Street, Broadway, the mills, the mines will close if half the buyers are broke. I cannot escape the conclusion that one of the essential parts of a national program of restoration must be to restore purchasing power to the farming half of the country. Without this the wheels of railroads and of factories will not turn.

Closely associated with this first objective is the problem of keeping the home-owner and the farm-owner where he is, without being dispossessed through the foreclosure of his mortgage. His relationship to the great banks of Chicago and New York is pretty remote. The two billion dollar fund which President Hoover and the Congress have put at the disposal of the big banks, the railroads and the corporations of the Nation is not for him.

His is a relationship to his little local bank or local loan company. It is a sad fact that even though the local lender in many cases does not want to evict the farmer or home-owner by foreclosure proceedings, he is forced to do so in order to keep his bank or company solvent. Here should be an objective of Government itself, to provide at least as much assistance to the little fellow as it is now giving to the large banks and corporations. That is another example of building from the bottom up.

One other objective closely related to the problem of selling American products is to provide a tariff policy based upon economic common sense rather than upon politics, hot-air, and pull. This country during the past few years, culminating with the Hawley-Smoot Tariff in 1929, has compelled the world to build tariff fences so high that world trade is decreasing to the vanishing point. The value of goods internationally exchanged is today less than half of what it was three or four years ago.

Every man and woman who gives any thought to the subject knows that if our factories run even 80 percent of capacity, they will turn out more products than we as a Nation can possibly use ourselves. The answer is that if they run on 80 percent of capacity, we must sell some goods abroad. How can we do that if the outside Nations cannot pay us in cash? And we know by sad experience that they cannot do that. The only way they can pay us is in their own goods or raw materials, but this foolish tariff of ours makes that impossible.

What we must do is this: revise our tariff on the basis of a reciprocal exchange of goods, allowing other Nations to buy and to pay for our goods by sending us such of their goods as will not seriously throw any of our industries out of balance, and incidentally making impossible in this country the continuance of pure monopolies which cause us to pay excessive prices for many of the necessities of life.

Such objectives as these three, restoring farmers' buying power, relief to the small banks and home-owners and a reconstructed tariff policy, are only a part of ten or a dozen vital factors. But they seem to be beyond the concern of a national administration which can think in terms only of the top of the social and economic structure. It has sought temporary relief from the top down rather than permanent relief from the bottom up. It has totally failed to plan ahead in a comprehensive way. It has waited until something has cracked and then at the last moment has sought to prevent total collapse.

It is high time to get back to fundamentals. It is high time to admit with courage that we are in the midst of an emergency at least equal to that of war. Let us mobilize to meet it.

(2) Franklin D. Roosevelt, nomination address (2nd July, 1932)

There are two ways of viewing the Government's duty in matters affecting economic and social life. The first sees to it that a favored few are helped and hopes that some of their prosperity will leak through, sift through, to labor, to the farmer, to the small business man. That theory belongs to the party of Toryism, and I had hoped that most of the Tories left this country in 1776

But it is not and never will be the theory of the Democratic Party. This is no time for fear, for reaction or for timidity. Here and now I invite those nominal Republicans who find that their conscience cannot be squared with the groping and the failure of their party leaders to join hands with us; here and now, in equal measure, I warn those nominal Democrats who squint at the future with their faces turned toward the past, and who feel no responsibility to the demands of the new time, that they are out of step with their Party.

Yes, the people of this country want a genuine choice this year, not a choice between two names for the same reactionary doctrine. Ours must be a party of liberal thought, of planned action, of enlightened international outlook, and of the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens.

Now it is inevitable - and the choice is that of the times - it is inevitable that the main issue of this campaign should revolve about the clear fact of our economic condition, a depression so deep that it is without precedent in modern history. It will not do merely to state, as do Republican leaders to explain their broken promises of continued inaction, that the depression is worldwide. That was not their explanation of the apparent prosperity of 1928. The people will not forget the claim made by them then that prosperity was only a domestic product manufactured by a Republican President and a Republican Congress. If they claim paternity for the one they cannot deny paternity for the other.

I cannot take up all the problems today. I want to touch on a few that are vital. Let us look a little at the recent history and the simple economics, the kind of economics that you and I and the average man and woman talk.

In the years before 1929 we know that this country had completed a vast cycle of building and inflation; for ten years we expanded on the theory of repairing the wastes of the War, but actually expanding far beyond that, and also beyond our natural and normal growth. Now it is worth remembering, and the cold figures of finance prove it, that during that time there was little or no drop in the prices that the consumer had to pay, although those same figures proved that the cost of production fell very greatly; corporate profit resulting from this period was enormous; at the same time little of that profit was devoted to the reduction of prices. The consumer was forgotten. Very little of it went into increased wages; the worker was forgotten, and by no means an adequate proportion was even paid out in dividends - the stockholder was forgotten.

And, incidentally, very little of it was taken by taxation to the beneficent Government of those years.

What was the result? Enormous corporate surpluses piled up - the most stupendous in history. Where, under the spell of delirious speculation, did those surpluses go? Let us talk economics that the figures prove and that we can understand. Why, they went chiefly in two directions: first, into new and unnecessary plants which now stand stark and idle; and second, into the call-money market of Wall Street, either directly by the corporations, or indirectly through the banks. Those are the facts. Why blink at them?

Then came the crash. You know the story. Surpluses invested in unnecessary plants became idle. Men lost their jobs; purchasing power dried up; banks became frightened and started calling loans. Those who had money were afraid to part with it. Credit contracted. Industry stopped. Commerce declined, and unemployment mounted.

And there we are today.

Translate that into human terms. See how the events of the past three years have come home to specific groups of people: first, the group dependent on industry; second, the group dependent on agriculture; third, and made up in large part of members of the first two groups, the people who are called "small investors and depositors." In fact, the strongest possible tie between the first two groups, agriculture and industry, is the fact that the savings and to a degree the security of both are tied together in that third group--the credit structure of the Nation.

Never in history have the interests of all the people been so united in a single economic problem. Picture to yourself, for instance, the great groups of property owned by millions of our citizens, represented by credits issued in the form of bonds and mortgages - Government bonds of all kinds, Federal, State, county, municipal; bonds of industrial companies, of utility companies; mortgages on real estate in farms and cities, and finally the vast investments of the Nation in the railroads. What is the measure of the security of each of those groups? We know well that in our complicated, interrelated credit structure if any one of these credit groups collapses they may all collapse. Danger to one is danger to all.

How, I ask, has the present Administration in Washington treated the interrelationship of these credit groups? The answer is clear: It has not recognized that interrelationship existed at all. Why, the Nation asks, has Washington failed to understand that all of these groups, each and every one, the top of the pyramid and the bottom of the pyramid, must be considered together, that each and every one of them is dependent on every other; each and every one of them affecting the whole financial fabric?

Statesmanship and vision, my friends, require relief to all at the same time.

Just one word or two on taxes, the taxes that all of us pay toward the cost of Government of all kinds.

I know something of taxes. For three long years I have been going up and down this country preaching that Government - Federal and State and local - costs too much. I shall not stop that preaching. As an immediate program of action we must abolish useless offices. We must eliminate unnecessary functions of Government - functions, in fact, that are not definitely essential to the continuance of Government. We must merge, we must consolidate subdivisions of Government, and, like the private citizen, give up luxuries which we can no longer afford.

By our example at Washington itself, we shall have the opportunity of pointing the way of economy to local government, for let us remember well that out of every tax dollar in the average State in this Nation, 40 cents enter the treasury in Washington, D. C., 10 or 12 cents only go to the State capitals, and 48 cents are consumed by the costs of local government in counties and cities and towns.

I propose to you, my friends, and through you, that Government of all kinds, big and little, be made solvent and that the example be set by the President of the United States and his Cabinet.

And talking about setting a definite example, I congratulate this convention for having had the courage fearlessly to write into its declaration of principles what an overwhelming majority here assembled really thinks about the 18th Amendment. This convention wants repeal. Your candidate wants repeal. And I am confident that the United States of America wants repeal.

Two years ago the platform on which I ran for Governor the second time contained substantially the same provision. The overwhelming sentiment of the people of my State, as shown by the vote of that year, extends, I know, to the people of many of the other States. I say to you now that from this date on the 18th Amendment is doomed. When that happens, we as Democrats must and will, rightly and morally, enable the States to protect themselves against the importation of intoxicating liquor where such importation may violate their State laws. We must rightly and morally prevent the return of the saloon.

To go back to this dry subject of finance, because it all ties in together--the 18th Amendment has something to do with finance, too - in a comprehensive planning for the reconstruction of the great credit groups, including Government credit, I list an important place for that prize statement of principle in the platform here adopted calling for the letting in of the light of day on issues of securities, foreign and domestic, which are offered for sale to the investing public.

My friends, you and I as common-sense citizens know that it would help to protect the savings of the country from the dishonesty of crooks and from the lack of honor of some men in high financial places. Publicity is the enemy of crookedness.

And now one word about unemployment, and incidentally about agriculture. I have favored the use of certain types of public works as a further emergency means of stimulating employment and the issuance of bonds to pay for such public works, but I have pointed out that no economic end is served if we merely build without building for a necessary purpose. Such works, of course, should insofar as possible be self-sustaining if they are to be financed by the issuing of bonds. So as to spread the points of all kinds as widely as possible, we must take definite steps to shorten the working day and the working week.

Let us use common sense and business sense. Just as one example, we know that a very hopeful and immediate means of relief, both for the unemployed and for agriculture, will come from a wide plan of the converting of many millions of acres of marginal and unused land into timberland through reforestation. There are tens of millions of acres east of the Mississippi River alone in abandoned farms, in cut-over land, now growing up in worthless brush. Why, every European Nation has a definite land policy, and has had one for generations. We have none. Having none, we face a future of soil erosion and timber famine. It is clear that economic foresight and immediate employment march hand in hand in the call for the reforestation of these vast areas.

In so doing, employment can be given to a million men. That is the kind of public work that is self-sustaining, and therefore capable of being financed by the issuance of bonds which are made secure by the fact that the growth of tremendous crops will provide adequate security for the investment.

Yes, I have a very definite program for providing employment by that means. I have done it, and I am doing it today in the State of New York. I know that the Democratic Party can do it successfully in the Nation. That will put men to work, and that is an example of the action that we are going to have.

Now as a further aid to agriculture, we know perfectly well-- but have we come out and said so clearly and distinctly?--we should repeal immediately those provisions of law that compel the Federal Government to go into the market to purchase, to sell, to speculate in farm products in a futile attempt to reduce farm surpluses. And they are the people who are talking of keeping Government out of business. The practical way to help the farmer is by an arrangement that will, in addition to lightening some of the impoverishing burdens from his back, do something toward the reduction of the surpluses of staple commodities that hang on the market. It should be our aim to add to the world prices of staple products the amount of a reasonable tariff protection, to give agriculture the same protection that industry has today.

And in exchange for this immediately increased return I am sure that the farmers of this Nation would agree ultimately to such planning of their production as would reduce the surpluses and make it unnecessary in later years to depend on dumping those surpluses abroad in order to support domestic prices. That result has been accomplished in other Nations; why not in America, too?

Farm leaders and farm economists, generally, agree that a plan based on that principle is a desirable first step in the reconstruction of agriculture. It does not in itself furnish a complete program, but it will serve in great measure in the long run to remove the pall of a surplus without the continued perpetual threat of world dumping. Final voluntary reduction of surplus is a part of our objective, but the long continuance and the present burden of existing surpluses make it necessary to repair great damage of the present by immediate emergency measures.

Such a plan as that, my friends, does not cost the Government any money, nor does it keep the Government in business or in speculation.

As to the actual wording of a bill, I believe that the Democratic Party stands ready to be guided by whatever the responsible farm groups themselves agree on. That is a principle that is sound; and again I ask for action.

One more word about the farmer, and I know that every delegate in this hall who lives in the city knows why I lay emphasis on the farmer. It is because one-half of our population, over 50,000,000 people, are dependent on agriculture; and, my friends, if those 50,000,000 people have no money, no cash, to buy what is produced in the city, the city suffers to an equal or greater extent.

That is why we are going to make the voters understand this year that this Nation is not merely a Nation of independence, but it is, if we are to survive, bound to be a Nation of interdependence--town and city, and North and South, East and West. That is our goal, and that goal will be understood by the people of this country no matter where they live.

Yes, the purchasing power of that half of our population dependent on agriculture is gone. Farm mortgages reach nearly ten billions of dollars today and interest charges on that alone are $560,000,000 a year. But that is not all. The tax burden caused by extravagant and inefficient local government is an additional factor. Our most immediate concern should be to reduce the interest burden on these mortgages.

Rediscounting of farm mortgages under salutary restrictions must be expanded and should, in the future, be conditioned on the reduction of interest rates. Amortization payments, maturities should likewise in this crisis be extended before rediscount is permitted where the mortgagor is sorely pressed. That, my friends, is another example of practical, immediate relief: Action.

I aim to do the same thing, and it can be done, for the small home-owner in our cities and villages. We can lighten his burden and develop his purchasing power. Take away, my friends, that spectre of too high an interest rate. Take away that spectre of the due date just a short time away. Save homes; save homes for thousands of self-respecting families, and drive out that spectre of insecurity from our midst.

Out of all the tons of printed paper, out of all the hours of oratory, the recriminations, the defenses, the happy-thought plans in Washington and in every State, there emerges one great, simple, crystal-pure fact that during the past ten years a Nation of 120,000,000 people has been led by the Republican leaders to erect an impregnable barbed wire entanglement around its borders through the instrumentality of tariffs which have isolated us from all the other human beings in all the rest of the round world. I accept that admirable tariff statement in the platform of this convention. It would protect American business and American labor. By our acts of the past we have invited and received the retaliation of other Nations. I propose an invitation to them to forget the past, to sit at the table with us, as friends, and to plan with us for the restoration of the trade of the world.

Go into the home of the business man. He knows what the tariff has done for him. Go into the home of the factory worker. He knows why goods do not move. Go into the home of the farmer. He knows how the tariff has helped to ruin him.

At last our eyes are open. At last the American people are ready to acknowledge that Republican leadership was wrong and that the Democracy is right.

My program, of which I can only touch on these points, is based upon this simple moral principle: the welfare and the soundness of a Nation depend first upon what the great mass of the people wish and need; and second, whether or not they are getting it.

What do the people of America want more than anything else? To my mind, they want two things: work, with all the moral and spiritual values that go with it; and with work, a reasonable measure of security--security for themselves and for their wives and children. Work and security--these are more than words. They are more than facts. They are the spiritual values, the true goal toward which our efforts of reconstruction should lead. These are the values that this program is intended to gain; these are the values we have failed to achieve by the leadership we now have.

Our Republican leaders tell us economic laws--sacred, inviolable, unchangeable--cause panics which no one could prevent. But while they prate of economic laws, men and women are starving. We must lay hold of the fact that economic laws are not made by nature. They are made by human beings.

Yes, when--not if--when we get the chance, the Federal Government will assume bold leadership in distress relief. For years Washington has alternated between putting its head in the sand and saying there is no large number of destitute people in our midst who need food and clothing, and then saying the States should take care of them, if there are. Instead of planning two and a half years ago to do what they are now trying to do, they kept putting it off from day to day, week to week, and month to month, until the conscience of America demanded action.

I say that while primary responsibility for relief rests with localities now, as ever, yet the Federal Government has always had and still has a continuing responsibility for the broader public welfare. It will soon fulfill that responsibility.

And now, just a few words about our plans for the next four months. By coming here instead of waiting for a formal notification, I have made it clear that I believe we should eliminate expensive ceremonies and that we should set in motion at once, tonight, my friends, the necessary machinery for an adequate presentation of the issues to the electorate of the Nation.

I myself have important duties as Governor of a great State, duties which in these times are more arduous and more grave than at any previous period. Yet I feel confident that I shall be able to make a number of short visits to several parts of the Nation. My trips will have as their first objective the study at first hand, from the lips of men and women of all parties and all occupations, of the actual conditions and needs of every part of an interdependent country.

One word more: Out of every crisis, every tribulation, every disaster, mankind rises with some share of greater knowledge, of higher decency, of purer purpose. Today we shall have come through a period of loose thinking, descending morals, an era of selfishness, among individual men and women and among Nations. Blame not Governments alone for this. Blame ourselves in equal share. Let us be frank in acknowledgment of the truth that many amongst us have made obeisance to Mammon, that the profits of speculation, the easy road without toil, have lured us from the old barricades. To return to higher standards we must abandon the false prophets and seek new leaders of our own choosing.

Never before in modern history have the essential differences between the two major American parties stood out in such striking contrast as they do today. Republican leaders not only have failed in material things, they have failed in national vision, because in disaster they have held out no hope, they have pointed out no path for the people below to climb back to places of security and of safety in our American life.

Throughout the Nation, men and women, forgotten in the political philosophy of the Government of the last years look to us here for guidance and for more equitable opportunity to share in the distribution of national wealth.

On the farms, in the large metropolitan areas, in the smaller cities and in the villages, millions of our citizens cherish the hope that their old standards of living and of thought have not gone forever. Those millions cannot and shall not hope in vain.

I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people. Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage. This is more than a political campaign; it is a call to arms. Give me your help, not to win votes alone, but to win in this crusade to restore America to its own people.

(3) Herbert Hoover, speech in New York City (31st October, 1932)

This campaign is more than a contest between two men. It is more than a contest between two parties. It is a contest between two philosophies of government.

We are told by the opposition that we must have a change, that we must have a new deal. It is not the change that comes from normal development of national life to which I object or you object, but the proposal to alter the whole foundations of our national life which have been builded through generations of testing and struggle, and of the principles upon which we have made this Nation. The expressions of our opponents must refer to important changes in our economic and social system and our system of government; otherwise they would be nothing but vacuous words. And I realize that in this time of distress many of our people are asking whether our social and economic system is incapable of that great primary function of providing security and comfort of life to all of the firesides of 25 million homes in America, whether our social system provides for the fundamental development and progress of our people, and whether our form of government is capable of originating and sustaining that security and progress.

This question is the basis upon which our opponents are appealing to the people in their fear and their distress. They are proposing changes and so-called new deals which would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life.

Our people should consider the primary facts before they come to the judgment - not merely through political agitation, the glitter of promise, and the discouragement of temporary hardships - whether they will support changes which radically affect the whole system which has been builded during these six generations of the toil of our fathers. They should not approach the question in the despair with which our opponents would clothe it...

The proposals of our opponents will endanger or destroy our system. I especially emphasize that promise to promote "employment for all surplus labour at all times." At first I could not believe that anyone would be so cruel as to hold out hope so absolutely impossible of realization to these 10,000,000 who are unemployed. And I protest against such frivolous promises being held out to a suffering people.

If it were possible to give this employment to 10,000,000 people by the Government, it would cost upwards of $9,000,000,000 a year. It would pull down the employment of those who are still at work by the high taxes and the demoralization of credit upon which their employment is dependent. It would mean the growth of a fearful bureaucracy which, once established, could never be dislodged.

(4) Franklin D. Roosevelt, speech in Boston (31st October, 1932)

At first the President refused to recognize that he was in a contest. But as the people with each succeeding week have responded to our program with enthusiasm, he recognized that we were both candidates. And then, dignity died.At Indianapolis he spoke of my arguments, misquoting them. But at Indianapolis he went further. He abandoned argument for personalities.

In the presence of a situation like this, I am tempted to reply in kind. But I shall not yield to the temptation to which the President yielded. On the contrary, I reiterate my respect for his person and for his office. But I shall not be deterred even by the President of the United States from the discussion of grave national issues and from submitting to the voters the truth about their national affairs, however unpleasant that truth may be.

The ballot is the indispensable instrument of a free people. It should be the true expression of their will; and it is intolerable that the ballot should be coerced - whatever the form of coercion, political or economic.

The autocratic will of no man - be he President, or general, or captain of industry - shall ever destroy the sacred right of the people themselves to determine for themselves who shall govern them.

An hour ago, before I came to the Arena, I listened in for a few minutes to the first part of the speech of the President in New York tonight. Once more he warned the people against changing - against a new deal - stating that it would mean changing the fundamental principles of America, what he called the sound principles that have been so long believed in in this country. My friends, my New Deal does not aim to change those principles. It does aim to bring those principles into effect.

Secure in their undying belief in their great tradition and in the sanctity of a free ballot, the people of this country - the employed, the partially employed and the unemployed, those who are fortunate enough to retain some of the means of economic well-being, and those from whom these cruel conditions have taken everything - have stood with patience and fortitude in the face of adversity.

There they stand. And they stand peacefully, even when they stand in the breadline. Their complaints are not mingled with threats. They are willing to listen to reason at all times. Throughout this great crisis the stricken army of the unemployed has been patient, law-abiding, orderly, because it is hopeful.

But, the party that claims as its guiding tradition the patient and generous spirit of the immortal Abraham Lincoln, when confronted by an opposition which has given to this Nation an orderly and constructive campaign for the past four months, has descended to an outpouring of misstatements, threats and intimidation.

The Administration attempts to undermine reason through fear by telling us that the world will come to an end on November 8th if it is not returned to power for four years more. Once more it is a leadership that is bankrupt, not only in ideals but in ideas. It sadly misconceives the good sense and the self-reliance of our people.

(5) Frances Perkins, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946)

Franklin Roosevelt was not a simple man. That quality of simplicity which we delight to think marks the great and noble was not his. He was the most complicated human being I ever knew; and out of this complicated nature there sprang much of the drive which brought achievement, much of the sympathy which made him like, and liked by, such oddly different types of people, much of the detachment which enabled him to forget his problems in play or rest, and much of the apparent contradiction which so exasperated those associates of his who expected "crystal clear" and unwavering decisions. But this very complicated of his nature made it possible for him to have insight and imagination into the most varied human experiences, and this he applied to the physical, social, geographical, economic and strategic circumstances thrust upon him as responsibilities by his times.

(6) James Farley, Behind the Ballots: The Personal History of a Politician (1938)

The intensity of the struggle which had to be waged to capture the Democratic presidential nomination for Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 was in reality a tremendous piece of good fortune - far more effective than if he had won the honor without a battle in a drab convention. The love of drama is age-old in the human heart, and by the time the Governor of New York was flying to Chicago to accept the nomination, the attention of every voter in America was turned his way.

Roosevelt played the role with consummate skill, and the country caught the picture of a smart and daring man who knew what was wrong with the economic machine and what was needed to set it right. His ability to discuss political issues in short, simple sentences also made a powerful impression. We noticed shortly after his acceptance speech, from reports of state and local leaders, that he had gotten away to a flying start. He never lost that advantage.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject