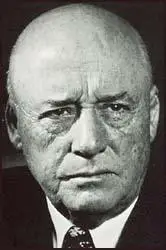

Sam Rayburn

Sam Rayburn, the son of a cavalryman in the Confederate Army, was born in Roane County, Tennessee, on 6th January, 1882. Five years later the family moved to a 40 acre cotton farm in Fannin County, Texas. After graduating from East Texas College he became a school teacher. Later he became a lawyer.

Rayburn was a member of the Democratic Party and in 1906 he won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives. In his third term he served as speaker. As he said later: "I saw that all my friends got the good appointments and that those who voted against me for Speaker got none."

In 1912 he was elected to Congress where he represented the Fourth Texas District. In his first term he was appointed to the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. He remained a member for the next 25 years.

In 1927 Rayburn married Metze Jones, the sister of his good friend, John Marvin Jones. The marriage lasted less than three months. Rayburn never remarried.

Rayburn worked closely with John Nance Garner. He was Garner's campaign manager in his attempt to become the Democratic presidential candidate. After Garner's defeat by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rayburn took part in the negotiations that enabled Garner to become vice president.

As chairman of the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee he played an important role in the establishing the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Communications Commission. He also joined forces with George Norris to pass the Rural Electrification Act.

In 1937 Rayburn became majority leader and helped He held the post for three years but in 1940 he was elected speaker. During the two periods of Republican majorities (1947-49 and 1953-55) he served as minority leader. He worked very closely with Lyndon Johnson and supported his attempts in 1956 and 1960 to become the presidential candidate.

Sam Rayburn died on 16th November, 1961. During his career he had developed a reputation for honesty. When he died his savings totaled $15,000.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert A. Caro, Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power (1983)

Rayburn who hated the railroads, whose freight charges fleeced the farmer, and the banks, whose interest charges fleeced the farmer, and the utility companies, which refused to extend their power lines into the countryside, and thus condemned the farmer to darkness. Rayburn who hated the "trusts" and the "interests"- Rayburn who hated the rich and all their devices. Rayburn who hated the Republican Party, which he regarded as one of those devices-hated it for currency policies that, he said, "make the rich richer and the poor poorer"; hated it for the tariff ("the robber tariff, the most indefensible system that the world has ever known," he called it; because the Republican Party "fooled ... the farmer into" supporting the tariff, he said, the rich "fatten their already swollen purses with more ill-gotten gains wrung from the horny hands of the toiling masses"); and hated it for Reconstruction, too: the son of a Confederate cavalryman who "never stopped hating the Yankees," Rayburn, a friend once said, "will not in his long lifetime forget Appomattox"; for years after he came to Congress, the walls of his office bore many pictures, but all were of one man-Robert E. Lee; in 1928, when his district was turning to the Republican Hoover over Al Smith, and he was advised to turn with it or risk losing his own congressional seat, he growled: "As long as I honor the memory of the Confederate dead, and revere the gallant devotion of my Confederate father to the Southland, I will never vote for electors of a party which sent the carpetbagger and the scalawag to the prostrate South with saber and sword." Rayburn who hated the railroads, and the banks, and the Republicans because he never forgot who he was, or where he came from.

(2) Alfred Steinberg, Sam Johnson's Boy (1968)

Rayburn came to Congress in 1913, with the Wilson influx, by the narrowest of margins. The opportunity arose when Choice Randell, representative from the Fourth Congressional District, quit to make an unsuccessful race for the Senate. Rayburn had seven opponents in the House contest, and it went down to the final wire in doubt. Of the 21,236 votes, he emerged with less than 25 per cent of the total. Yet his vote of 4,983 gave him the election, for the highest vote of any other candidate was 4,493.

When Rayburn first came to Washington, John Nance Garner let him share his office until one became available for him. And as the bald but fair-haired boy of Garner, Rayburn was given a coveted post on the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee. Here old-timers recalled that he buttered up Committee Chairman William C. Adamson, who also became his sponsor.

But before long Garner realized that Rayburn intended to compete with him eventually for House leadership. In 1924 their relationship grew strained, said Tom Connally, when Garner tried to get House Democrats to elect him minority leader. By chance he discovered that protégé Rayburn was quietly boosting Finis Garrett of Tennessee, the state where Rayburn was born, for the same post. When Garrett won, Garner lost his enthusiasm for the double-dealer, though he let him stay in his private drinking club.

During Rayburn's early House period he was known for his coarse practical jokes. But he subdued himself on purpose, adopted a dour expression, and clothed himself like an undertaker. Despite his early poverty, while in Congress he managed to acquire a comfortable two-story white colonial house on a substantial farm-ranch near Bonham. This was essential for prestige purposes to impress visiting politicians, who noted the permanent roots in the soil of Texas with approbation. Lyndon Johnson caught the significance of this facade on early visits to Bonham. He listened with interest when Rayburn told company he was "busy as a cranberry merchant" on the farm and detailed so many orders to "Old Henry," his colored herdsman, that he gave the impression he was first a farmer and second a member of Congress.

The Lyndon Johnson-Sam Rayburn relationship developed quickly into a son-father kinship. "Sam had married Metze Jones, the sister of Marvin Jones, a member of the House from Amarillo, in 1927," said Tom Connally. "In fact, Sam and Marvin got married at the same time in a double ceremony. But on their joint honeymoon, the bridegrooms did such powerful drinking that the brides fled in the middle of one night and later got divorces." After that Rayburn called himself a bachelor and became a doting uncle to his flock of nephews and nieces.

(3) Robert Dallek, Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and His Times (1991)

No one in the House was more important to Lyndon Johnson, however, than Sam Rayburn, his fellow Texan from Bonham in the northeast corner of the state. At the age of fifty-five, after twenty-four years in the House, Rayburn had become Majority Leader in January 1937. A short, stocky man with a bald head, broad shoulders, and a thick-set, powerful neck, Rayburn dressed in dark suits that gave him the "somber, immaculate" look of "a capable undertaker." A normally "poker-faced expression" or "stern demeanor" added to his grave appearance. A bachelor with few interests outside of the House of Representatives, which he once described as "my life and my love," Rayburn was a lonely man. On Sundays, he would awake unhappy at the prospect of a day without the excitement of the Capitol. "God help the lonely, for loneliness consumes people," he once said when facing a quiet day.