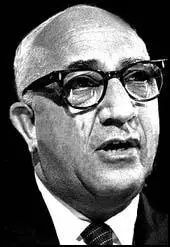

Carmine Bellino

Carmine Bellino was born in New Jersey in 1905. After graduating from New York University in 1928 Bellino worked as an accountant in New York City.

In 1934 Bellino joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation and served as an administrative assistant to, J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, until the end of the Second World War. He then served as assistant director of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1945-46) and War Assets Administration (1946-47). According to Robert Maheu, Bellino was also employed by Joseph Kennedy as his accountant and personal secretary.

Bellino specialized in dealing with organized crime and corrupt trade union officials and served on two congressional investigations into labour racketeering. In 1955, Robert Kennedy became chief counsel of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He recruited Bellino as one of his staff members.

Bellino served as a consultant to various congressional committees. He also worked as an accountant in New York City and Washington.

In 1961 John F. Kennedy appointed him as his special consultant until and held the post until the president was assassinated in 1963. Bellino now became a partner at Wright, Long and Company. He also worked part time for the Atomic Energy Commission and various congressional committees.

During the Watergate Scandal Bellino was appointed chief investigator of the Senate Select Committee on the 1972 Presidential Campaign Activities. Bellino had worked with Lou Russell at the FBI and the House Committee on Un-American Activities. According to Jim Hougan (Secret Agenda) Russell had helped James W. McCord to "sabotage the break-in".

Russell was interviewed by the FBI soon afterwards. He claimed that during the break-in he was in his rooming house. The FBI agents did not believe him but none of the burglars claimed he had been involved in the conspiracy and he was released. Bob Woodward discovered that Russell had been working for James W. McCord. He interviewed Russell but decided that he had not taken part in the Watergate break-in. According to Woodward: "He (Russell) was just an old drunk".

Soon afterwards Russell received a phone call from Bellino. It is not known was was said but as a result of this conversation Russell went to stay with Bellino's friend, William Birely, on the top floor of the Twin Towers complex in Silver Spring, Maryland. Birely was also a close friend of Lee R. Pennington. Both men had been active members of the Sons of the American Revolution. John Leon later claimed that Lou Russell was working as a spy for the Democratic Party and was reporting to Bellino about the Watergate break-in.

During the Watergate investigation George Bush accused Bellino of organizing a wiretap to be placed on the phones of Engelhard Industries for John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential elections. It later emerged that this story was true. Charles W. Engelhard, a South African diamond merchant, had discovered that Kennedy was having an affair with a nineteen year old student at Radcliffe College. Engelhard had attempted to employ a private detective in Boston to obtain photographs of Kennedy with this student. The detective refused and informed Kennedy of what was going on and this resulted in Bellino organizing the wiretap.

In 1979 Bellino was appointed as chief investigator of the Senate Judiciary Committee. He held this post for the next two years.

Carmine Bellino died on 29th February, 1990.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Kennedy, The Enemy Within (1960)

"When our plane touched down at the Willow Run airport near Detroit, Pierre Salinger, brief case in hand, the inevitable cigar in his mouth, and an almost visible halo of excitement encircling his head, was waiting for us in the sweltering summer sun. It was July 28, 1958 - just a week before Jimmy Hoffa was due to appear before our Committee for his second series of hearings.

Salinger was a dark, extremely alert and intelligent young man who could grasp the importance of a document better than almost anyone on the staff. So his urgent telephone call about a document he had got hold of in a particularly sticky investigation had brought Carmine Bellino and me rushing from Washington.

What he had was a signed, sworn affidavit that in 1949 Hoffa had demanded and received cash pay-offs from Detroit laundry owners in return for a sweetheart contract. The payments, it said, had been arranged through the labor consultant from Jack (Bab) Bushkin and Joe Holtzman, two of Hoffa's most helpful pals in Detroit.

Our Committee had already shown that Hoffa made 'business' deals with employers; we had shown that he kept huge sums of cash on hand. But he consistently had denied to us that the cash was pay-offs from employers.

This affidavit was important evidence to the contrary. Salinger had received it from William Miller, a former Detroit laundry owner, only a few hours before our arrival. For three consecutive years, Miller said, he and all the other laundry owners in the city had contributed to a purse raised for Mr. Hoffa by the Detroit Institute of Laundering. The cash was collected by two officials of the Institute, John Charles Meissner and Howard Balkwill, who saw to it that Mr. Hoffa got the money.

Meissner had been executive secretary-treasurer of the management group. He was now retired. Balkwill was still the chief executive officer. Meissner and Balkwill, then, were the first men in Detroit we wanted to see to get corroboration of Miller's statement.

As Pierre Salinger drove through the traffic toward Meissner's suburban home, he filled us in on the background of the 1949 dispute between the laundering management group and the Teamsters Union - the dispute that had led to the sweetheart contract and the pay-off.

Laundry drivers of Teamsters Local 285 had still been working a six-day week that year - and, as testimony showed, they were tired of it. In February, their local union head, Isaac Litwak, sat down with Laundry Institute officials headed by Meissner and Balkwill, determined to get a five-day work week for his union members. Across the table from Litwak, the laundry representatives put their heads together, counted costs, and decided they could not possibly afford a five-day week. Negotiations ran on for weeks, then months. In May, Litwak, impatient, threatened a strike.

Management negotiators again put their heads together. While they could not afford a five-day week, neither could they afford a strike. And as strike talk continued, they became alarmed. Obviously, they concluded, they couldn't deal with Litwak. He had even thrown one of their lists of proposals in the wastebasket. They decided they had to go to some higher Teamster authority. According to his own affidavit, William Miller suggested getting in touch with Jimmy Hoffa to see if something could be 'worked out'.

Balkwill and Meissner agreed to try. After several days, Miller's affidavit continued, they reported that they had been successful. They could obtain a contract for a continued six-day week - in return for a cash fund to pay off Jimmy Hoffa. Were the owners all agreeable? According to Miller, they were.

When we arrived at the home of John Charles Meissner, in a quiet Detroit residential section, it was humid and hot and clouds were blotting out the sun. A thunderstorm was brewing. Meissner was puttering in his garden. He was a tanned, healthy-looking man of medium build. As we walked across his lawn to where he was kneeling, he had a friendly though inquisitive look on his face.

We introduced ourselves. We showed him our credentials and sat down - Salinger and Bellino on a wooden bench, I on an overturned pail. We told him outright, without softening the blow, why we had come: about the pay-off in 1949 to Jimmy Hoffa. I told him we wanted his co-operation; that we needed his help. He was shocked. 'Never heard of such a thing,' he said, and vehemently continued to deny that the laundry owners had paid a 'shakedown' to anyone during the 1949 negotiations. We evidently didn't understand, he said, that we were talking about reputable businessmen, people with a standing in the community.

Mr. Meissner has an honest way about him. Without blinking, he looked me straight in the eye. And he lied. Mr. Meissner lied then and continued to lie for several days thereafter.

Carmine Bellino now set out to try to track down Howard Balkwill while Pierre Salinger and I continued our discussion with Mr. Meissner. We went with him into his house and I asked if we might use his telephone to call William Miller. When Miller answered, I asked him to refresh Mr. Meissner's memory. He agreed. I handed the phone to the former secretary of the Institute.

Salinger and I stood nearby while they talked. Mr. Miller, apparently, was making his position clear, telling Mr. Meissner what he had sworn to in the affidavit.

We heard Meissner say: 'Bill, I just don't know what you are talking about.' He put down the receiver.

We then served a subpoena on him, ordering him to come to Washington. He became angry. And so did his wife, who had heard the telephone conversation and our discussions with her husband. She ordered Salinger and me from her house. We left, and went off to see how Carmine was making out in his interview with William Balkwill.

(2) Evan Thomas, Robert Kennedy: His Life (2000)

When the Democrats won back control of the Senate in 1955, Bobby became chief counsel of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. With communist hunting out of favour in the wake of Joseph McCarthy's excesses, Kennedy steered the committee towards government corruption. But he discovered his true interest in the netherwold of organized crime...

In the summer of 1956, Kennedy began hearing from muckraking reporters who were writing stories about corruption in the trade union movement. Unions, with their vast pension funds and need for muscle, made ideal targets of opportunity for organized crime. Ever since the Kefauver hearings in 1951, the public had been at least dimly aware that labor was being infiltrated by the mob. On the Waterfront, the 1954 movie about corruption in the Longshoremen's Union, dramatized the problem. But it took some muckraking reporters to begin to expose the vast reach of labor racketeering.

Uncovering mob ties to the unions was a dangerous business. In April 1956, some hoods threw acid into the eyes of a crusading labor reporter, Victor Riesel... (the mobster later beat the rap). But reporters began nudging Kennedy: 'Shouldn't his congressional investigators take a look at the broader problem of labor racketeering?' Kennedy hesitated. He was only just beginning to see the dimensions of the threat. Anyway, he wasn't sure his committee had jurisdiction. The Senate Labor Committee was jealous of his purview, but its members were also leery of offending Big Labor, which generously donated to the political parties.

A relentless and abrasive newsman named Clark Mollenhoff found the key to Kennedy: he baited him for being gutless. 'Was Kennedy scared?' Mollenhoff taunted. 'Afraid of the power of the unions?' He didn't have to ask if Kennedy was physically afraid. Kennedy took the bait. In August 1956 Kennedy got the members of the investigations subcommittee to authorize a preliminary look into racketeering by the labor unions.

Although he could not yet see the scale of his crusade or where it would take him, Kennedy had at last found an enemy worthy of his passions. But, as usual, family duty came first. Before RFK could take on a thorough rackets investigation, he had to attend to his brother Jack's political ambitions. Already plotting his path to the White House after four years in the Senate, Jack Kennedy wanted to make a try at getting on the ticket with Adlai Stevenson...

JFK lost, narrowly, to Senator Estes Kefauver, the Tennessee senator who had first won national attention with televised hearings on organized crime in 1951...In fact, JFK's defeat really had been a blessing. Stevenson's campaign was doomed. But JFK had established himself as the bright young face of the party's future, the hope to recapture the White House in 1960...And the victory of Estes Kefauver, whom RFK had dismissed as a drunken lightweight, opened his eyes to another possibility--a way to make a name and win headlines while chasing bad guys....On election day, Kennedy voted for Eisenhower.

Then it was back to his new cause, investigating labor corruption. Kennedy saw a chance to top the 1951 Kefauver hearings by investigating the growing links between labor and organized crime. Such an investigation would be politically risky, given the power of Big Labor in the Democratic Party. Still, Kennedy started at the top: he picked as his first target the nation's largest and richest union, the Teamsters, the 1.3-million-man union that dominated the trucking industry.

The union had been 'mobbed up,' quietly infiltrated by gangsters who saw the Teamsters' $250 million pension fund as a honey pot. In November, Kennedy traveled west under an alias (Mr. Rogers), talking to newspapermen who had written stories about labor corruption. With him was Carmine Bellino, an accountant and former FBI agent who, as a Senate staffer, had seen two previous congressional investigations of labor racketeering wilt under political pressure. 'Unless you are prepared to go all the way,' he advised, 'don't start it.' Kennedy replied, 'We're going all the way.' In Los Angeles, they heard grisly stories of strong-arm tactics. They learned about the union organizer who had been warned to stay out of San Diego by the jukebox operators. He went anyway and was knocked unconscious. When he awoke the next morning, 'he was covered with blood and had terrible pains in his stomach,' Kennedy wrote. 'The pains were so intense that he was unable to drive back to his home in Los Angeles and stopped at a hospital. There was an emergency operation. The doctors removed from his backside a large cucumber. Later, he was told that if he ever returned to San Diego it would be a watermelon.'

(3) Robert Maheu, Next to Hughes (1992)

Shortly after I formed Maheu Associates, Jim O'Connell and Bob Cunningham, who had worked with me in the FBI and were now CIA agents, wanted me to perform "cut-out" operations for the Agency i.e., those jobs with which the Company could not be officially connected.

At that time, however, I shared an office with Carmine Bellino, an ex-FBI agent who had created a very successful practice as both a CPA and an investigator. For years, Carmine had been a close associate of old Joe Kennedy, serving as both his personal accountant and private gumshoe. Now that the Kennedy boys were coming of age, Carmine began doing the same for them. And young Bobby - who fifteen years later would be thought of as a liberal White Knight - had started his career working as Joseph McCarthy's assistant counsel, outranked on McCarthy's staff only by the infamous Roy Cohn.

Because of Bobby, the CIA told me that if I were to work with the Agency, I would have to move away from Carmine and any possible Kennedy connection. I said I couldn't afford to move out. So the Company put me on a monthly retainer of $500, thereby becoming my first steady client and enabling me to move into an office of my own.

The CIA's dislike of McCarthy was admirable, but not without self-interest. To its credit, the Agency recognized he was evil and acted accordingly. But this was when McCarthy was going after the Department of State like a dog after a bone. State was run by John Foster Dulles. The CIA was run by his brother, Allen. Like much in politics, the CIA's ideological stand was built upon a very personal foundation.

(4) Seymour Hersh, The Dark Side of Camelot (1998)

Senator Kennedy's scramble to protect his future presidential reputation began in earnest in late 1959, when a political opponent discovered that he was carrying on an affair with a nineteen-year-old student. She was studying at Radcliffe College, the woman's college of Harvard University, on whose board of overseers Kennedy then served. His indiscretion was known to many: Kennedy's car and driver had been seen picking up and dropping off the student at her dormitory.

In this instance, Kennedy's biggest worries came not from Republicans but from his fellow Democrats, who were eager to find ways to discredit their competition. Word of the liaison reached Charles W. Engelhard, a South African diamond merchant and investor with corporate offices in New Jersey. Engelhard had endorsed Robert B. Meyner, the Democratic governor of New Jersey, who had presidential ambitions of his own; he and Meyner could not resist a chance to get rid of Kennedy. The two men arranged for one of Engelhard's aides to approach a former New York City policeman, then a private investigator, and offer him $10,000 to fly to Boston and take incriminating photographs of Kennedy with the Radcliffe student. However, the former policeman was a staunch Kennedy supporter. He turned down the job and, through a mutual friend, brought the plan to the attention of a politically connected Democratic lawyer in Washington. The lawyer, who had spent many years as a Senate aide, immediately arranged to see Jack Kennedy.

"Evelyn Lincoln shows me in," the lawyer, who did not wish to be identified, recalled in a 1996 interview for this book, "and I show him the name of the girl. He says, "My God! They got her name: He started to explain - some bullshit - and I said, `I'm not really interested. I just wanted to let you know.' He was so appreciative that I'd tipped him off."

It was clear, the lawyer said, that "Charley Engelhard was trying to get the goods on Kennedy to knock him out of the running. They were going to set him up." Senator Kennedy, in the meeting, had exclaimed, "That goddamned Charley Engelhard. I'm going to give it to him up to there"- drawing his hand across his neck. Changing the subject, the lawyer asked Kennedy what he could do to help him win the Democratic nomination. He vividly recalled the answer: "I need money. I can't ask my father to pay for everything. Raise money."

Months later, during the campaign, the lawyer bumped into Kennedy and was thanked anew for his timely information. Kennedy told the lawyer he had assigned Carmine Bellino, one of his longtime assistants, to find out what was going on. Bellino, he said, had "put in a wire" on the Engelhard Industries official who had tried to hire the former New York City policeman. The lawyer raised an objection to the use of wiretaps and Kennedy reassured him, explaining, "We're not tapping his phone - just recording who he called."

In a meeting with the lawyer after the election, Kennedy reported that he was being urged by many ranking Democrat members of the Senate to name Engelhard ambassador to a high-profile embassy. "I'm going to get him," Kennedy said, with a laugh. "I'm going to send him to one of the boogie republics in Central Africa."

Engelhard, who died in 1971 one of the world's richest men, never got his embassy, but the Kennedy administration did name him as the American representative to the Independence Day ceremonies in Gabon and Zambia. Kennedy, as we have seen, continued his relationship with the student. After his inauguration, he arranged for her to be named a special assistant to McGeorge Bundy, who had been dean of faculty at Harvard. She remained on Bundy's White House staff until late 1962. "It was very embarrassing," the woman recalled in one of our interviews. "It put McGeorge in a very creepy situation."

(5) Webster G. Tarpley & Anton Chaitkin, George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography (2005)

One of the major sub-plots of Watergate, and one that will eventually lead us back to the documented public record of George Bush, is the relation of the various activities of the Plumbers to the wiretapping of a group of prostitutes who operated out of a brothel in the Columbia Plaza Apartments, located in the immediate vicinity of the Watergate buildings. Among the customers of the prostitutes there appear to have been a US Senator, an astronaut, A Saudi prince (the Embassy of Saudi Arabia is nearby), US and South Korean intelligence officials, and above all numerous Democratic Party leaders whose presence can be partially explained by the propinquity of the Democratic National Committee offices in the Watergate. The Columbia Plaza Apartments brothel was under intense CIA surveillance by the Office of Security/Security Research Staff through one of their assets, an aging private detective out of the pages of Damon Runyon who went by the name of Louis James Russell. Russell was, according to Hougan, especially interested in bugging a hot line phone that linked the DNC with the nearby brothel. During the Watergate break-ins, James McCord's recruit to the Plumbers, Alfred C. Baldwin, would appear to have been bugging the telephones of the Columbia Plaza brothel.

Lou Russell, in the period between June 20 and July 2, 1973, was working for a detective agency that was helping George Bush prepare for an upcoming press conference. In this sense, Russell was working for Bush.

Russell is relevant because he seems (although he denied it) to have been the fabled sixth man of the Watergate break-in, the burglar who got away. He may also have been the burglar who tipped off the police, if indeed anyone did. Russell was a harlequin who had been the servant of many masters. Lou Russell had once been the chief investigator for the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He had worked for the FBI. He had been a stringer for Jack Anderson, the columnist. In December, 1971 he had been an employee of General Security Services, the company that provided the guards who protected the Watergate buildings. In March of 1972 Russell had gone to work for James McCord and McCord Associates, whose client was the CREEP. Later, after the scandal had broken, Russell worked for McCord's new and more successful firm, Security Associates. Russell had also worked directly for the CREEP as a night watchman. Russell had also worked for John Leon of Allied Investigators, Inc., a company that later went to work for George Bush and the Republican National Committee. Still later, Russell found a job with the headquarters of the McGovern for President campaign. Russell's lawyer was Bud Fensterwald, and sometimes Russell performed investigative services for Fensterwald and for Fensterwald's Committee to Investigate Assassinations. In September, 1972, well after the scandal had become notorious, Russell seems to have joined with one Nick Beltrante in carrying out electronic countermeasures sweeps of the DNC headquarters, and during one of these he appears to have planted an electronic eavesdropping device in the phone of DNC worker Spencer Oliver which, when it was discovered, re-focussed public attention on the Watergate scandal at the end of the summer of 1972.

Russell was well acquainted with Carmine Bellino, the chief investigator on the staff of Sam Ervin's Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Practices. Bellino was a Kennedy operative who had superintended the seamy side of the JFK White House, including such figures as Judith Exner, the president's alleged paramour. Later, Bellino would become the target of George Bush's most revealing public action during the Watergate period. Bellino's friend William Birely later provided Russell with an apartment in Silver Spring, Maryland, (thus allowing him to leave his room in a rooming house on Q Street in the District), a new car, and sums of money.

Russell had been a heavy drinker, and his social circle was that of the prostitutes, whom he sometimes patronized and sometimes served as a bouncer and goon. His familiarity with the brothel milieu facilitated his service for the Office of Security, which was to oversee the bugging and other surveillance of Columbia Plaza and other locations.

Lou Russell was incontestably one of the most fascinating figures of Watergate. How remarkable, then, that the indefatigable ferrets Woodward and Bernstein devoted so little attention to him, deeming him worthy of mention in neither of their two books. Woodward and met with Russell, but had ostensibly decided that there was "nothing to the story. Woodward claims to have seen nothing in Russell beyond the obvious "old drunk."

The FBI had questioned Russell after the DNC break-ins, probing his whereabouts on June 16-17 with the suspicion that he had indeed been one of the burglars. But this questioning led to nothing. Instead, Russell was contacted by Carmine Bellino, and later by Bellino's broker Birely, who set Russell up in the new apartment (or safe house) already mentioned, where one of the Columbia Plaza prostitutes moved in with him...

Leaving the hospital on June 20, Russell was still very weak and pale. But now, although he remained on the payroll of James McCord, he also accepted a retainer from his friend John Leon, who had been engaged by the Republicans to carry out a counter investigation of the Watergate affair. Leon was in contact with Jerris Leonard, a lawyer associated with Nixon, the GOP, the Republican National Committee, and with Chairman George Bush. Leonard was a former assistant attorney general for civil rights in the Nixon administration. Leonard had stepped down as head of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) on March 17, 1973. In June, 1973 Leonard was special counsel to George Bush personally, hired by Bush and not by the RNC. Leonard says today that his job consisted in helping to keep the Republican Party separate from Watergate, deflecting Watergate from the party "so it would not be a party thing." As Hougan tells it, "Leon was convinced that Watergate was a set-up, that prostitution was at the heart of the affair, and that the Watergate arrests had taken place following a tip-off to the police; in other words, the June 17 burglary had been sabotaged from within, Leon believed, and he intended to prove it." Integral to Leon's theory of the affair was Russell's relationship to the Ervin committee's chief investigator, Carmine Bellino, and the circumstances surrounding Russell's relocation to Silver Spring in the immediate aftermath of the Watergate arrests. In an investigative memorandum submitted to GOP lawyer Jerris Leonard, Leon described what he hoped to prove: that Russell, reporting to Bellino, had been a spy for the Democrats within the CRP, and that Russell had tipped off Bellino (and the police) to the June 17 break-in. The man who knew most about this was, of course, Leon's new employee, Lou Russell."

Is it possible that Jerris Leonard communicated the contents of Leon's memorandum to the RNC and to its Chairman George Bush during the days after he received it? It is possible. But for Russell, the game was over: on July 2, 1973, barely two weeks after his release from the hospital, Russell suffered a second heart attack, which killed him. He was buried with quite suspicious haste the following day. The potential witness with perhaps the largest number of personal ties to Watergate protagonists, and the witness who might have re-directed the scandal, not just towards Bellino, but toward the prime movers behind and above McCord and Hunt and Paisley, had perished in a way that recalls the fate of so many knowledgeable Iran-contra figures.

With Russell silenced forever, Leon appears to have turned his attention to targeting Bellino, perhaps with a view to forcing him to submit to depositioning or other questioning in which questions about his relationship to Russell might be asked. Leon, who had been convicted in 1964 of wiretapping in a case involving El Paso Gas Co. and Tennessee Gas Co., had weapons in his own possession that could be used against Bellino. During the time that Russell was still in the hospital, on June 8, Leon had signed an affidavit for Jerris Leonard in which he stated that he had been hired by Democratic operative Bellino during the 1960 presidential campaign to "infiltrate the operations" of Albert B. "Ab" Hermann, a staff member of the Republican National Committee. Leon asserted in the affidavit that although he had not been able to infiltrate Hermann's office, he observed the office with field glasses and employed "an electronic device known as 'the big ear' aimed at Mr. Hermann's window." Leon recounted that he had been assisted by former CIA officer John Frank, Oliver W. Angelone and former Congressional investigator Ed Jones in the anti-Nixon 1960 operations.

(6) Jack Sonthor, Bush, Rove engaged in dirty tricks of their own dating to Watergate (June, 2005)

The main reason we have another Bush criminal in the White House. Bush Sr. accepted illegal campaign contributions from none other than Nixon himself during his failed Senate campaign in 1970. Some $106,000 came from Nixon's secret campaign slush fund called "Operation Townhouse," with at least $55,000 in cash that was not reported as required by law.

During Watergate, Bush Sr. headed the Republican National Committee and did everything he could to keep Watergate quiet. In 1973, Bush even came up with a phony plan to divert attention by accusing the late Carmine Bellino, a committee investigator for the U.S. Senate committee investigating Watergate, of trying to bug the hotel where Nixon stayed preparing for the 1960 debates with JFK. The investigation into that lie and dirty trick went on for more than two months, causing delays in the Watergate committee's proceedings.

Bellino was eventually cleared, of course, but not before Bush almost helped destroy the Watergate investigation. He might have succeeded had people like Felt not been there to blow the whistle. That's why people like Liddy and Buchanan and Bush call Felt a traitor, when he is a real hero who understood that reporting what he saw through the normal channels of the Justice Department was not going to work since the Justice Department destroyed evidence and worked directly in cahoots with the criminal Nixon White House.

(7) Richard D. Mahoney, Sons and Brothers (1999)

The Warren Report was drawing new fire from serious scholars. Edward J. Epstein, in his book Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth, demonstrated that the Commission's investigation had been sloppy and never proved that Oswald had acted alone or even was the killer. Dick Goodwin wrote a laudatory review of the book in the Washington Post's Book Week, calling for a new investigation by an independent group.

A few days later, in a late-night conversation with Bobby at his UN Plaza apartment, Goodwin recounted his doubts about the Warren Commission.

"Bobby listened silently, without objection," Goodwin later wrote, "his inner tension or distaste revealed only by the circling currents of Scotch in the glass he was obsessively rotating between his hands, staring at the floor in a posture of avoidance."

He finally looked up when Goodwin was finished. "I'm sorry, Dick," he said. "I just can't focus on it."

But Goodwin pressed the issue. "I think we should find our own investigator - someone with absolute loyalty and discretion."

"You might try Carmine Bellino. He's the best in the country."

That was as much as Kennedy would say.

(8) Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat and the CIA (1984)

It was at about this time that Russell received a telephone call from a prominent man - Carmine Bellino, an "investigative accountant," whose life had been spent in close association with the Kennedy family. He had known Lou Russell when the latter had been chief investigator for the House Committee on Un-American Activities, and he was telephoning Russell at the suggestion of a mutual friend, John Leon.

Leon later said that Bellino had wanted to learn everything he could about the attack on the DNC. Knowing of Russell's employment by McCord and suspecting his involvement in the break-in, Leon urged Bellino to contact the private detective. At the time, Bellino was the de facto point man of the congressional investigation then impending. Under the authority of Senator Edward Kennedy, the then chairman of the Senate's Administrative Practices Committee, Bellino was laying the groundwork for the day when he would be appointed chief investigator for the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities (the Ervin committee).

We do not know what Bellino said to Russell or what Russell said to Bellino. Soon after the call, however, a Good Samaritan came to Russell, offering sanctuary. The Samaritan was William Birely, Bellino's close friend and longtime stockbroker. Asked if there was any connection between his friendship with Bellino and his subsequent generosity to Russell, Birely insists that there was not. Similarly, Birely says, his friendship with Lee Pennington was also a coincidence: both he and Pennington had long served together as executive officers in various patriotic societies based in Washington.

It was "out of the goodness of my heart," Birely recalls, that he offered to rescue Russell from his squalid quarters in the capital. Russell accepted the offer, and was soon resident in an apartment on the top floor of the Twin Towers complex in Silver Spring, Maryland, just across the District line. Provided with "walking around money" and a better car than he had been driving until then, Russell found that his situation had improved dramatically.

"I pitied him," Birely told me. "There was nothing more to it than that. Lou had just picked himself up. He'd stopped drinking. He had great hopes for his work with McCord and then, all of a sudden, he was out of a job. The Watergate business just devastated him."

In fact Russell was not "out of a job." Despite McCord's arrest, and the apparent dissolution of McCord Associates, Inc., Russell remained in the employ of the Watergate burglar, albeit under different auspices. On June 9th McCord had rented office space at the Arlington Towers complex in Rosslyn on the Virginia side of the Potomac. There McCord established a new firm, Security International, Inc., headed by a former CIA officer named William Shea (whose wife, Theresa, had previously worked as McCord's secretary). The new firm was to achieve remarkable success; whereas McCord Associates had won only two clients (the CRP and the RNC) after two years of trying, Security International signed twenty-five to thirty (never identified) new clients in its first nine months of existence. Moreover, even while the Arlington Towers were unusually secure, so also was the suite of offices that McCord had rented for his new firm. The doors of that firm were kept locked around the clock (even while its employees worked inside), and no outsiders were permitted to enter. Salesmen and others who called in person were told that all business had to be transacted over the telephone. It was while living at the Twin Towers in Silver Spring as a guest of William Birely's that Russell continued to work for McCord under the auspices of Security International. According to Russell's daughter, Jean Hooper, "Mr. McCord was a pallbearer at my dad's funeral (in July i973). And when it was over, Mr. McCord came to me with my dad's last paycheck. I think it was for $285-something like that."

Which raises the question: Why did - how could - McCord keep Russell on the payroll for more than a year after the Watergate arrests and, indeed, even after the detective was incapacitated by a heart attack (in April 1973)? If we are to believe the impression given at the time, McCord was in desperate financial straits. Raising bail was said to be a serious problem, his family was allegedly hard put to make ends meet and so forth. And yet, despite these difficulties, McCord was able to pay Russell a good salary and, what is more, to reject a $105,000 publishing advance for what appear to have been artistic reasons.