Isaac Brodsky

Isaac Brodsky, the son of Yisrael Brodsky, a Jewish merchant, was born in the village of Sofiyivka near Berdyansk on 6th January 1884. He studied at Odessa Art Academy and the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. In 1916 he joined the Jewish Society for the Encouragement of the Arts and was deeply influenced by the work of Ilya Repin.

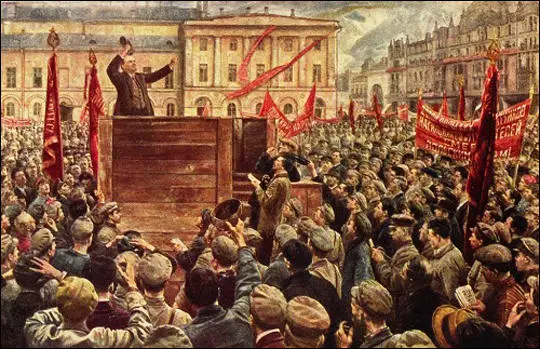

In 1917 he painted the portrait of Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government. One of the founders of the Socialist Realist art movement he produced several paintings dedicated to the events of the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War.

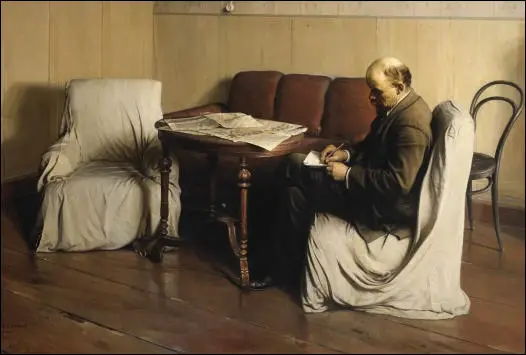

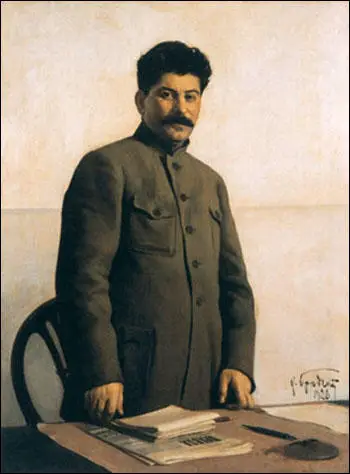

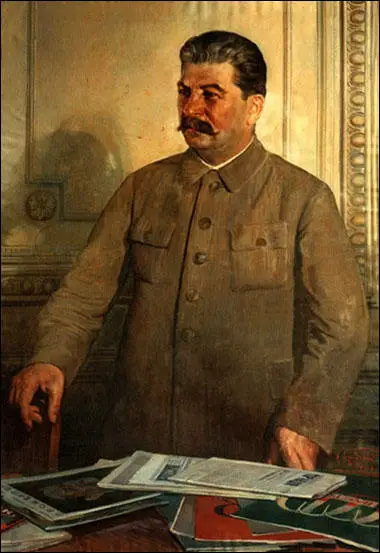

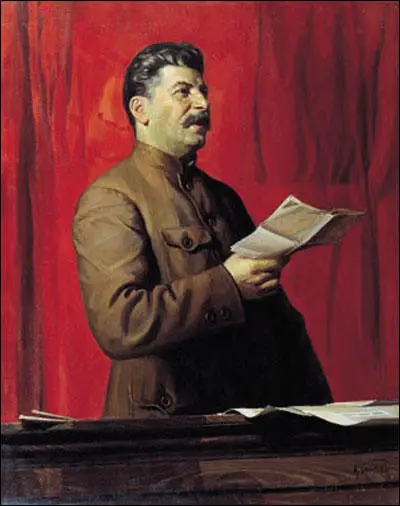

Brodsky was a committed supporter of the Bolsheviks and painted portraits of Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Gregory Ordzhonikidze.

In 1934 he was appointed Director of the All-Russian Academy of Arts. His pupils included the well-known Soviet painters, Piotr Belousov, Nikolai Timkov, Alexander Laktionov, Vasily Surikov, Yuri Neprintsev, Piotr Vasiliev and Mikhail Kozell.

Isaac Brodsky died on 14th August 1939. He was an avid art collector and after his death his apartment on Arts Square in St. Petersburg was declared a national museum.

Primary Sources

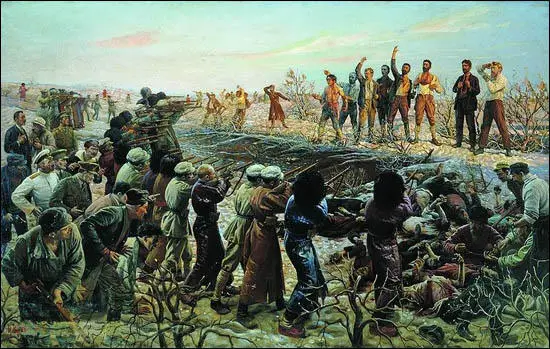

(1) Execution of the 26 Baku Commissars (19th September, 2014)

In the history and the mythology of the October Revolution and the Soviet civil war, the 26 Baku Commissars have played a role similar to the 300 Spartans in the history of ancient Greece. Their death would be immortalized in Soviet times through movies, books, artwork, stamps, and public works, and even cities and towns would be named after some of them.

After the Bolshevik revolution of October/November 1917, a Soviet (council) of workers, villagers, and soldiers was created in Baku. This council came to power from April 13 to July 25, 1918 and created an executive organ, the Council of Popular Commissars, formed by an alliance of Bolsheviks and leftist Socialist Revolutionaries, and presided by a famous Bolshevik revolutionary, the Armenian Stepan Shahumian. It was known as the Commune of Baku.

The Commune faced various problems, from the shortage of food and supplies to the threat posed by the invading Turks. The Red Army units hurriedly organized by the Commune were defeated by the Islamic Army of the Caucasus, an Ottoman army unit organized by order of Minister of War Enver Pasha on the basis of the local Tatar (Azerbaijani) population, and retreated to Baku in July 1918.

The military defeat provoked the rise of a coalition of rightist Socialist Revolutionaries, Social Democrats, and Armenian Revolutionary Federation members, which asked help from British forces stationed in Persia to counterbalance the Ottoman advance. The Commune transferred power to the new provisional government formed by the coalition, called the Centro-Caspian Dictatorship, and left Baku for Astrakhan, which was under Bolshevik control. However, the new authorities arrested the members of the Commune under charges of embezzlement and treason.

However, a new attack of the Ottoman forces over Baku prevented the trial of the military tribunal, and, according to Soviet historiography, on 14 September 1918, during the fall of Baku to the Turks, Red Army soldiers broke into their prison and freed the 26 prisoners; they then boarded a ship to Astrakhan, which changed its destination to Krasnovodsk, on the other side of the Caspian Sea. They were promptly arrested by local authorities of the Transcaspian provisional government, also anti-Soviet, on September 17, and three days later executed by a firing squad between the stations of Pereval and Akhcha-Kuyma on the Transcaspian Railway, apparently under British pressure.

Although they have been named as “commissars,” not all of them were officials and not all of them were Bolsheviks. Among the executed men, there were Russians, Jews, Armenians, Georgians, Azerbaijanis, Greeks, and Latvians.

(1) In November, 1918, General Peter Wrangel was fighting with General Anton Denikin in the Kuban area.

In the course of the last few months my command had received considerable reinforcements. In spite of heavy losses, its strength was almost normal. We were well supplied with artillery, technical equipment, telephones, telegraphs, and so on, which we had taken from the enemy. When the Reds had succeeded in making themselves masters of the Kuban district they had recourse to conscription there. Now these forced recruits were deserting en masse, and coming over to us to defend their homes. They were good fighters, but once their own village was cleared of Reds, many of them left the ranks to cultivate their land once more.

(4) Leaflet issued by the Bolsheviks in Mourmansk in 1919.

For the first time in history the working people have got control of their country. The workers of all countries are striving to achieve this object. We in Russia have succeeded. We have thrown off the rule of the Tsar, of landlords, and of capitalists. But we have still tremendous difficulties to overcome. We cannot build a new society in a day. We deserve to be left alone. We ask you, are you going to crash us? To help give Russia back to the landlords, the capitalists and Tsar?

(5) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971)

Treason had nests among the staff and the commanding officers; in fact, everywhere. The enemy knew where to strike and almost always did so with certainty. It was discouraging. Soon after my arrival, I visited the front-line batteries. The disposition of the artillery was being explained to me by an experienced officer, a man with a face roughened by wind and with impenetrable eyes. He asked for permission to leave me for a moment, to give some orders over the field-telephone. A few minutes later two shells dropped, fork-wise, fifty steps away from where we were standing; a third dropped quite close to us. I had barely time to lie down, and was covered with earth. The officer stood motionless some distance away, his face showing pale through his tan. Strangely enough, I suspected nothing at the moment; I thought it was simply an accident. Two years later I suddenly remembered the whole affair, and, as I recalled it in its smallest detail, it dawned on me that the officer was an enemy, and that through some intermediate point he had communicated with the enemy battery by telephone, and had told them where to fire. He ran a double risk – of getting killed along with me by a White shell, or of being shot by the Reds. I have no idea what happened to him later.

I had no sooner returned to my carriage than I heard rifle-shots all about me. I rushed to the door. A White airplane was circling above us, obviously trying to hit the train. Three bombs dropped on a wide curve, one after another, but did no damage. From the roofs of our train rifles and machine-guns were shooting at the enemy. The airplane rose out of reach, but the fusillade went on – it seemed as if every one were drunk. With considerable difficulty I managed to stop the shooting. Possibly the same artillery officer had sent word as to the time of my return to the train. But there may have been other sources as well.

The more hopeless the military situation of the revolution, the more active the treason. It was necessary, no matter what the cost, to overcome as quickly as possible the automatic inertia of retreat, in which men no longer believe that they can stop, face about, and strike the enemy in the chest. I brought about fifty young party men from Moscow with me on the train. They simply outdid themselves, stepping into the breach and fairly melting away before my very eyes through the recklessness of their heroism and sheer inexperience. The posts next to theirs were held by the fourth Latvian regiment. Of all the regiments of the Latvian division that had been so badly pulled to pieces, this was the worst. The men lay in the mud under the rain and demanded relief, but there was no relief available. The commander of the regiment and the regimental committee sent me a statement to the effect that unless the regiment was relieved at once “consequences dangerous for the revolution” would follow. It was a threat. I summoned the commander of the regiment and the chairman of the committee to my car. They sullenly held to their statement. I declared them under arrest. The communications officer of the train, who is now the commander of the Kremlin, disarmed them in my compartment. There were only two of us on the train staff; the rest were fighting at the front. If the men arrested had showed any resistance, or if their regiment had decided to defend them and had left the front line, the situation might have been desperate. We should have had to surrender Sviyazhsk and the bridge across the Volga. The capture of my train by the enemy would undoubtedly have had its effect on the army. The road to Moscow would have been left open. But the arrest came off safely. In an order to the army, I announced the commitment of the commander of the regiment to trial before the revolutionary tribunal. The regiment remained at its post. The commander was merely sentenced to prison.

The communists were explaining, exhorting, and offering example, but agitation alone could not radically change the attitude of the troops, and the situation did not allow sufficient time for that. We had to decide on sterner measures. I issued an order which was printed on the press in my train and distributed throughout the army: “I give warning that if any unit retreats without orders, the first to be shot down will be the commissary of the unit, and next the commander. Brave and gallant soldiers will be appointed in their places. Cowards, bastards and traitors will not escape the bullet. This I solemnly promise in the presence of the entire Red Army.”

Of course the change did not come all at once. Individual detachments continued to retreat without cause, or else would break under the first strong onset. Sviyazhsk was open to attack. On the Volga, a steamboat was held ready for the staff. Ten men of my train crew, mounted on bicycles, were on guard over the pathway between the staff headquarters and the steamship landing. The military Soviet of the Fifth army proposed that I move to the river. It was a wise suggestion, but I was afraid of the bad effect on an army already nervous and lacking in assurance. Just at that time, the situation at the front suddenly grew worse. The fresh regiment on which we had been banking left its post, with its commissary and commander at its head, and seized the steamer by threat of arms, intending to steam to Nijni-Novgorod.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject