Irmgard Paul

Irmgard Paul was born in Berchtesgaden, Germany on 28th May, 1934. Her parents, Max Paul and Albine Pöhlmann, had married in January 1933. Max was a porcelain painter, whose work was popular with tourists who visited the town in the Bavarian Alps. (1)

Adolf Hitler had his holiday home, Berghof, in the neighbouring hamlet of Obersalzberg. Both parents were supporters of the Nazi Party: "After years of being made to feel like beggars and scum, they lent an eager ear to the man who told them that Germany was not only a worthy nation but a superior one. Anyone who promised economic stability would capture the nation's mind and soul as well. Of all the Weimar politicians, only Hitler understood fully that playing up patriotism and making false promises to every interest group would garner a following. And most important, perhaps, he realized that instilling fear of a vaguely defined enemy - the conspirators of world Jewry - would bring a suspicious and traumatized people, including my own mother and father, to his side." (2)

Irmgard Paul later recalled in her autobiography, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005): "Hitler's portrait hung above the dark sofa in the family room and his presence influenced our domestic lives, our thoughts, and the stories and memories I gathered". However, Irmgard insists she never heard about events such as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). "I heard no tales of Kristallnacht that so infamously and unashamedly revealed the intent to dehumanize Jews. These ominous portents on the seemingly bright horizon were smoothed over by the Nazi leaderships' frenzied moral outrage and denunciation of whole segments of the population. Silently my father and mother held on to their delusion that indeed a happy future lay ahead in our cheery home with Hitler's red wax portrait watching over us." (3)

Irmgard Paul and her Nazi Family

Irmgard's name reflected her parents commitment to the idea of the Master Race: "The Nazi propaganda machine stressed the superiority and importance of things Germanic... and names were among the most important badges of this identity. From now on girls would be called... Irmgard, Helga, Gundrun, Gertrude, Hildegard, Brunhilde, Sigrid, Ingrid, Edeltraud, or the more exotic Gotelinde, Gerlinde, Ortrun, or Heidrun." (4)

Joseph Goebbels made it clear that under the new government married German women would be expected to stay at home and have children: "A fundamental change is necessary. At the risk of sounding reactionary and outdated, let me say this clearly: The first, best, and most suitable place for the women is in the family, and her most glorious duty is to give children to her people and nation, children who can continue the line of generations and who guarantee the immortality of the nation. The woman is the teacher of the youth, and therefore the builder of the foundation of the future. If the family is the nation’s source of strength, the woman is its core and centre. The best place for the woman to serve her people is in her marriage, in the family, in motherhood." (5)

Adolf Hitler argued that the Nazi government was protecting the best interests of women by encouraging them to get married and have children: "The so-called granting of equal rights to women, which Marxism demands, in reality does not grant equal rights but constitutes a deprivation of rights, since it draws the woman into an area in which she will necessarily be inferior. The woman has her own battlefield. With every child that she brings into the world, she fights her battle for the nation." (6)

Irmgard Paul's mother agreed with this viewpoint and loved being a full-time housemaker and mother. "Unfortunately, father's long work hours did not translate into an ample income. Mother's weekly household money was just enough to meet our modest, basic needs, making her thrift a necessary virtue... Mother rented out my bedroom to summer guests who flocked in increasing numbers to Berchtesgaden to breathe the same air as Hitler and perhaps even get a glimpse of him." (7)

The Nazi government brought in measures to encourage women to get married and have large families. Young couples intending to get married could apply in advance for the interest-free loan of up to 1,000 Reichsmarks provided that the prospective wife had been in employment for at least six months in the two years up to the passing of the law. Importantly, she had to give up her job by the time of the wedding and undertake not to enter the labour market again until the loan was paid off, unless her husband lost his job in the meantime. To stimulate production the loans were issued not in cash but in the form of vouchers for furniture and household equipment. By the end of 1934, around 360,000 women had given up work in order to get married. (8)

As Richard Evans, the author of The Third Reich in Power (2005), has pointed out: "That this was not a short-term measure was indicated the terms of repayment, which amounted to 1 per cent of the capital per month, so that the maximum period of the loan could be as much as eight and a half years... However, the loans were made more attractive, and given an additional slant, by a supplementary decree issued on 20 June 1933 reducing the amount to be repaid by a quarter for each child born to the couple in question. With four children, therefore, couples would not have to repay anything." (9)

Albine Paul gave birth to a second daughter, Ingrid, on 12th July, 1937. This was a difficult time for Irmgard: "I was not happy that Ingrid was now being wheeled up and down the road in my baby carriage. Besides, father would come home these days and check out the baby before he told me about his day and what flowers he had painted. I resented the huge amount of time mother seemed to be spending with the baby. All day long she was either nursing it, cooking the mushy food it could eventually eat, and endlessly washing and hanging diapers, baby clothes, and bibs." (10)

As a child, one of Irmgard's best friends was Ruth Ungerer, the daughter of a barber. She was shocked to be told by her mother one day that in future Ruth would be known as Ingrid: "Ruth is a Jewish name and with her father joining the border police it is better for her not to have a Jewish name." Irmgard later commented: "I had no idea what Jewish was, but it could not be good if you had to give up your name because of it." (11)

Meeting Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler spent a lot of time at the Berghof. During her childhood Irmgard Paul often saw Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Albert Speer, and other Nazi leaders in official black cars driving up the mountain on their way to Obersalzberg.

One day she was with Tante Emilie, who used to look after her when her mother was busy, when she saw Hitler's car: "We ran toward the main road. Hitler's trip up the mountain that day must have been widely announced because we joined an enthusiastic horde of onlookers lining the road, waving and cheering. As always when a large crowd was at attention, Hitler stood up in his open, black Mercedes with the red leather upholstery. His arm was stretched out straight."

Tante Emilie disapproved of Hitler and "had made up her mind that she would not raise her army to greet either the Führer or the swastika flag fluttering next to the Mercedes emblem, an encircled star, on his car." Irmgard Paul happily raised her arm and called out "Heil Hitler" with the rest of the crowd. "As the big, black limousine passed by, even I could see the Führer's face. Tante Emilie kept her arm close by her side at first, but then, probably realizing that she risked imprisonment or worse, she raised it slowly, without shouting."

On the way home, Irmgard heard Tante Emilie grumbling to herself: "How could I have been so weak as to let myself do that?" Years later she told Irmgard: "As the car moved by at its unhurried pace, Hitler's black eyes fastened on her and kept staring at her until, as if hypnotized, she raised her arm in the salute she hated. Tante Emile could never forget this victory of Hitler's will over hers." Irmgard's mother was furious when she heard this story and told Tante Emilie that "you are in the wrong camp". (12)

Albine Paul's father was a strong opponent of Hitler. He had been an active trade unionist and was furious when Hitler ordered the Sturm Abteilung (SA) to destroy the labour movement. Their headquarters throughout the country were occupied, union funds confiscated, the unions dissolved and the leaders arrested. Large numbers were sent to concentration camps. Within a few days 169 different trade unions were under Nazi control. (13)

Hitler gave Robert Ley the task of forming the German Labour Front (DAF). Ley, in his first proclamation, stated: "Workers! Your institutions are sacred to us National Socialists. I myself am a poor peasant's son and understand poverty... I know the exploitation of anonymous capitalism. Workers! I swear to you, we will not only keep everything that exists, we will build up the protection and the rights of the workers still further." (14)

Three weeks later Hitler decreed a law bringing an end to collective bargaining and providing that henceforth "labour trustees", appointed by him, would "regulate labour contracts" and maintain "labour peace". Since the decisions of the trustees were to be legally binding, the law, in effect, outlawed strikes. Ley promised "to restore absolute leadership to the natural leader of a factory - that is, the employer... Only the employer can decide." (15)

In 1937, Irmgard's Pöhlmann grandparents had a holiday in Berchtesgaden. "The degree to which my parents and my grandparents diverged in their views on Hitler and his politics had reached a new high. Most of their discussions, encouraged perhaps by Hitler's presence on the mountain, ended in verbal clashes followed by hostile silences. Grandfather called Hitler a fly-by-night, no-good maniac who had seduced the German people and addled their collective minds and would ultimately betray them." (16)

One day the family decided to pay a visit to the Berghof. "As we made our way uphill the conversations between the grown-ups led to the same clashes they had at home. Mother and father praised Hitler for saving Germany, and grandfather maligned everything the Führer had done. I didn't understand the debates, and their vehemence made me feel anxious and helpless. I wondered who was right and who was wrong, since both sides carried the weight of authority." (17)

When they reached Hitler's house they joined a crowd of people milling around and waiting outside a fence. Hitler eventually came out to talk to the crowd. He liked to have his photograph taken with young children and when he saw blond-haired Irmgard he picked her up: "I remember being ill at ease perched on his knee suspiciously studying his mustache, his slicked-back, oily hair, and the amazingly straight side part, while at the same time acutely sensing the importance of the moment and of the man. The applauding crowd disconcerted me as well, but I smiled bravely, checking every few seconds to make sure my family was close by. An official photographer snapped a photo. At one moment I saw my grandfather turning away brusquely, striking the air angrily with his cane, trying to find an escape through the people. He had obviously had enough of the spectacle, feeling most likely that his granddaughter was being misused by the man for whom he had nothing but contempt."

After being held by Hitler she felt herself to be an important person: "I basked in the admiration that this short, unintended moment on Hitler's lap brought me and felt lucky to live so near the Führer. I was developing, quite according to Nazi plans, into a true little Nazi child in spite of my grandfather's ire.... I saw the Führer drive up or down the Obersalzbergstrasse quite a few times over the next few years but never came that close to him again." (18)

Irmgard's grandfather feared that Hitler's policies would lead to war. During the First World War he had fought on the Western Front: "My grandfather had told me about the war in France, and I had seen tears well up in his eyes when he talked of friends and comrades who had died there next to him in the mud. He had instilled in me a very deep fear of war. War was worse than any story; it was real, it killed, it was horrible." (19)

Second World War

On 23rd August, 1939, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin signed the Nazi-Soviet Pact. A week later, on 1st September, the two countries invaded Poland. Within 48 hours the Polish Air Force was destroyed, most of its 500 first-line planes having been blown up by German bombing on their home airfields before they could take off. Most of the ground crews were killed or wounded. In the first week of fighting the Polish Army had been destroyed. On 6th September the Polish government fled from Warsaw. (20)

"Eight months after the invasion, I saw mother's face fall as she read the official letter that called my father, now thirty-four, to join the army. The reality of war and the inevitability of our personal involvement suddenly became clear to her in a way it had not before... I did not want him to leave at all, but I understood already that he had to do what the Führer wanted. Mother had a measure of certainty in her voice when she promised us that he would not be gone long and life would be just the same when he came back." (21)

Max Paul joined the Nachrichten Ersatz Korps and after a few months training he was sent to join the occupying forces in Normandy and took part in the fighting in Dunkirk. After six months in France he returned in October 1940 for a week's leave. "I felt my face turn red as a beet when he opened the door, while Ingrid cried big tears of joy. I thought my little sister a cry baby and was slightly annoyed that she did not want to let go let go of him and give me my turn in his strong arms. For the entire week the two of us vied for his attention, and I resented visits from friends who came by to discuss the war situation with him and wish him well. He seemed more serious and preoccupied than I remembered." (22)

The people of Berchtesgaden became disillusioned when Adolf Hitler declared war on the Soviet Union on 22nd June, 1941. "Regardless of the propaganda Hitler dished out to the gullible Germans, the mood among the women of Berchtesgaden grew more somber at the news that the was was expanding to the east. It was beginning to dawn on everyone that the war was expanding to the east. It was beginning to dawn on everyone that this war could take longer than they had originally thought." (23)

Max Paul was killed in France on 5th July, 1941. "People in Berchtesgaden reacted in two different ways to his death - our friends, relatives, and neighbours, with sadness and compassion; the Nazi officials in our lives with pompous, irrelevant condolences. My father's boss, Herr Adler, who for unknown reasons was not drafted, came by - in his S.A. uniform, no less - a few days after the news arrived and said in an oily voice to my stricken mother, Chin up, Frau Paul, chin up. He died for the Führer." (24)

"The morning after we got the death notice, my teacher, Fräulein Stöhr, a fanatical Nazi, ordered me to stand up in front of the class and tell everyone how proud I was that my father had given his life for the Führer. I stood before those hundred children, my face burning, my hurt heart thumping. I clenched my fists and swallowed hard, determined not to cry or otherwise show anyone how I felt. I forced myself to drain all emotion from my voice, even forcing my mouth into a grin, and said, Yes, we heard yesterday that my father died in France for the Führer. Heil Hitler. My face was flushed, but I made sure to walk calmly back to my seat." (25)

A Nazi Education

It has been estimated that by 1936 over 32 per cent of teachers were members of the Nazi Party. This was a much higher figure than for other professions. Teachers who were members, wore their uniforms in the classroom. The teacher would enter the classroom and welcome the group with a ‘Hitler salute’, shouting "Heil Hitler!" Students would have to respond in the same manner. (26) By 1938 two-thirds of all elementary school teachers were indoctrinated at special camps in a compulsory one-month training course of lectures. What they learned at camp they were expected to pass on to their students. (27)

Irmgard Paul first went to her Berchtesgaden school in April 1940. "From the day mother delivered me into Fräulein Stöhr's clutches it was obvious that this woman was a fanatical Nazi. A true believer. Surely she had become a teacher not because she had an affinity for children but because she wanted to tyrannize them. The Nazi doctrines designed to raise citizens wholly obedient to the Führer's bidding captivated and excited her... The war had already eaten into resources and materials, as well as the supply of male teachers, most of whom were drafted. As a result, Fräulein Stöhr got to sink her fangs into one hundred children belonging to three different grades. We were huddled together in her stark, whitewashed classroom learning the basics by rote plus a bit of local history, needlework for the girls, and geography."

The curriculum did not include anything like "political education", but "Fräulein Stöhr knew how to use occasions like my father's death, Hitler's birthday, good or bad news from the front, or the visit of a prominent local Nazi to indoctrinate us.... Hitler found the brown eyes and dark hair dominant among the valley's people not to his liking, suspecting undesirable Italian or even Slavic influences, and accordingly, Fräulein Stöhr seemed to prefer the Nordic-looking children."

Irmgard Paul had a strong dislike for her teacher: "Prussian obedience, order, and discipline as well as blind submission to Nazi ideology were Fräulein Stöhr's undisputed forte. In these efforts she was aided by two canes cut from a filbert bush, one thin and one thick. She used them for slight infractions.... Over the course of two years she used her filbert canes on my hands at least four times, three times for whispering answers to kids she had called on. Each time I had to leave my crowded bench and walk, embarrassed and infuriated, to the front of the classroom and onto the podium to receive a couple of stinging lashes on my outstretched hand." (28)

One of Irmgard's classmates was Albert Speer, the son of Albert Speer, a senior figure in the Nazi government. "We were quite in awe of Albert, knowing that he came from the inner circle of Nazi leadership, and we hoped, of course, that he would divulge some real secrets of life up there behind the fence and the big gate." The children of Arthur Bormann, Martin Bormann and Fritz Saukel, also sent their children to the school. "It seemed very egalitarian, except that these particular children to the local schools. It seemed very egalitarian, except that these particular children arrived at school in black, sparkling clean Mercedes-Benzes driven by S.S. chauffeurs, just as Hitler himself would have, and whenever sirens announced an air raid they were picked up and whisked away to safety in luxurious bunkers on the mountain." (29)

At school Irmgard was brainwashed into accepting Nazi views on the Jewish race. "We used a book with page after page showing the physical differences between Jews and Germans in grotesque drawings of Jewish noses, lips, and eyes. The book encouraged every child to note these differences and to bring anyone who bore Jewish features on the attention of our parents or teachers. I was horrified by the crimes Jewish people were being accused of - killing babies, loan-sharking, basic dishonesty, and conspiring to destroy Germany and rule the world. The description of the Jewish people would convince any child that these were monsters, not people with sorrows and joys like ours." (30)

In 1943 Irmgard got a new teacher. "Fräulein Hoffmann, a slender, short woman of indeterminate age, welcomed me and assigned me a seat. After the first morning I knew that she was not the ogre that Fräulein Stöhr had been but that she too was a Nazi fanatic, more dangerous, it turned out, than Stöhr... Monday mornings each pupil had to weigh in with at least two pounds of used paper and a ball of smoothed-out silver aluminum foil to help with the war effort."

One day Irmgard asked her grandfather asked if she could take some of his old journals to school to help Germany win the war. "He looked at me as if he had not quite understood my question and then said in a calm, icy tone that not a sliver bf any of his magazines would go to support the war of that scoundrel Hitler... How dare he not support the war that we were told every day was a life-and-death struggle for the German people? I left the workshop without the journals but what I felt would be a permanent resentment against my grandfather."

Soon afterwards Fräulein Hoffmann invited Irmgard Paul to her home "to have a special treat of hot chocolate and cookies at her house". It was not long before Irmgard discovered why she had been asked to visit her teacher: "After a few polite words she asked point-blank what my grandfather thought about Adolf Hitler and what he said about the war. I was still angry with my grandfather but stalled, sitting uncomfortably on the moss green, upholstered chair in Fräulein Hoffmann's living room, weighing my feelings against my answer. On the one hand, grandfather was withholding paper for the war effort... On the other hand, he was my grandfather. I knew the twinkle in his eyes when he was amused and had seen tears running down his face when one after another the messages arrived that both his apprentices had been killed on the eastern front... After much too long a pause I came to the decision that I liked this nosy teacher less than my grandfather."

Irmgard Paul commented in her autobiography, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005): "Although I did not know it that day, Fräulein Hoffmann was a Nazi informer, and my telling the truth would have sent grandfather to a concentration camp. Something had made me protect my grandfather, but it took a long time before I realized how lucky I (and he) had been in making that decision. On that particular day, though, I felt thoroughly sick of these conflicts forced on me by adults." (31)

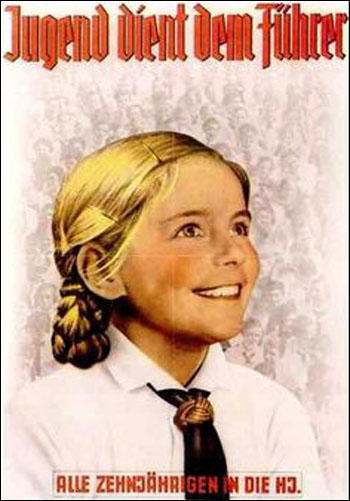

German Girls' League

All young girls in Nazi Germany had to join the German Girls' League (Bund Deutscher Mädel), the female branch of the Hitler Youth movement. There were two general age groups: the Jungmädel, from ten to fourteen years of age, and older girls from fifteen to twenty-one years of age. All girls in the BDM were constantly reminded that the great task of their schooling was to prepare them to be "carriers of the... Nazi world view". (32)

In April, 1944, just before she reached the age of ten, Irmgard Paul joined the Jungmädel. "On a rainy afternoon in April the new H.J. members were verpflichtet (inducted, or sworn in), and mother and Ingrid came to watch in the drizzle... The slim dark blue skirt, the white blouse with white buttons already impressed with BDM, and the black kerchief fastened at the neck by a brown leather knot were hand-me-downs from Trudi."

"At our first Appell (drill and meeting) we were lined up by size four rows deep and called to order for learning how to march in place. The group leader, Heidi Seiberl, daughter of one of the local clothing-and-fabric merchants, called out as loud as she could, left, right, left, right... The boys were already marching past us, their steps sounding firm and the commands loud, better perhaps than our walking shoes and girls' voices ever would. Their red-haired leader... marched alongside the troop giving commands, while a couple of boys beat drums ahead of the marchers. Finally we too marched through the town from one end to the other, under the old arches along the castle square... I was completely seduced by a feeling of belonging, of being united with all young Germans wearing the uniform." (33)

"In addition to marching drills we Jungmädel trained for sports competitions, hiked, sang a great deal, and listened to many lectures and speeches by senior leaders. They always said that every boy and girl had to do his or her share to win the war and that we must believe that the Führer was invincible and Germany's only salvation. No one asked a question; it was not called for and we were much too well indoctrinated to do so." (34)

Members of the BDM were encouraged to communicate with members of the German armed forces. "The Jungmädel sent packages filled with mittens and wrist warmers that we had knitted in rainbow colours from unraveled wool, some food, and tobacco to soldiers in the field. The packages were small, since we hadn't much to give, but we were told that what made them special were our personal notes to the soldiers. I found it difficult to think of something cheery, let alone meaningful, to write to a soldier I did not know and who might die soon... We sent the packages to randomly assigned military addresses at one or another of our far-flung but increasingly closer fronts." (35)

Death of Adolf Hitler

On 21st July, 1944, Irmgard Paul heard about the attempt on the life of Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg and his group (July Plot): "The Führer himself goes on the radio, assuring the German people that he is alive and well, that he has not sustained more than a few cuts and bruises. Providence has intervened in his behalf, he says. The revolt, hatched by German generals, has been completely suppressed. All the conspirators have been killed or have committed suicide." (36)

The following day, Albine Paul, was talking to the artist, Hans Jörg Schuster, about the attempt to kill Hitler. Schuster argued that there need to be a purge against those who were not completely loyal to the Führer. Suddenly she interrupted him and said, "You know what I wish? I wish they had killed Hitler and then there would be a chance to end the war." Schuster responded with the words: "You are a traitor too! I am going to the Gestapo right now and tell them about you!" The expected visit from the Gestapo never came and so Schuster must have changed his mind. (37)

Adolf Hitler committed suicide on 30th April 1945. The following day a young Schutzstaffel soldier visited Albine and asked if she had any civilian men's clothing. "He wanted to shed his uniform and get away. Mother hushed me back to bed and gave the man a pair of my father's tweed knickers, a shirt, and a jacket. There were more knocks that night and the next, and more jackets and pants disappeared. I heard the transactions with increasing resentment over my mother's largesse with my dead father's clothes. I wondered if she knew that even now helping soldiers desert was treason." (38)

On 3rd May, 1945, a messenger from the mayor's office in Berchtesgaden walked from house to house. He told them to "hang a white sheet over your balconies or out of the windows... and to open the door without resistance to any foreign soldier who wants to enter". Albine carried out these instructions. She also took down Hitler's portrait from the wall and destroyed it. The following day the 3rd Division of the United States Army arrived in town.

Irmgard Paul later commented: "I had sometimes tried to imagine what the U.S. soldiers would be like. My knowledge of Americans came from... Nazi propaganda, which held that the United States was an instrument of the Jews who wanted to destroy Germany, and that the country's white inhabitants were uncultured barbarians who ate from tin cans." Irmgard was surprised when she first saw the soldiers: "They looked fierce but to my surprise just as young and handsome as our soldiers had been. Fleeting as my impressions were, I found the Americans to look more human than I thought possible."

Her views about the occupation troops changed a few days later: "A contingent of French and Moroccan soldiers had arrived in Berchtesgaden almost simultaneously with the U.S. troops, we became alarmed and less optimistic about our personal safety... The soldiers of both armies were given free rein to plunder the town for several days after the surrender - permission that resulted in many vivid accounts of theft and rape." (39)

On 17th October, 1946, Irmgard Paul, new teacher, Imma Krumm, told the children: "You probably all know that, thanks to God, justice was done in Nuremberg yesterday and the Nazi criminals met with their deserved death." Bernhard Sauckel, the son of Fritz Saukel one of the men executed after the Nuremberg War Trials was in her class: "I suddenly saw that Bernhard Sauckel, who sat a few benches ahead of mine, had fainted... Most of us liked Bernhard Sauckel, a funny little guy with very small eyes and a heavy Saxonian accent. An awful silence followed the incident, and in utter confusion we tried in our minds to separate the Bernhard we knew from what his father had done." (40)

Life in America

In 1958 Irmgard Paul spent time in London learning English before moving to the United States. She married a psychoanalyst and lived in Manhattan. The couple had two children, Peter and Karen. In the 1960s she was an opponent of the Vietnam War: "I think the war in Vietnam was a watershed the way people viewed this topic. Before Vietnam there was a conviction of America’s righteousness and the total evil of Germany. Then Americans saw that even democratically elected leaders could lead a country into a war with which not everyone agreed. This humbling experience caused people to reflect on the courage it takes to stand up against one’s government and how long - even in an open society - it can take to change foreign policies." (41)

In the 1980s she studied for degrees at Columbia University and Harvard University. (42) She also began work on an autobiography, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005). "I began writing about my father’s death just a few years after the war when I attended the Gymnasium (high school). In class, one day, I read my essay out loud and was stunned to realize that it had moved my classmates to tears. I rewrote that story many times. The decision to put the memories of those mean years into a book was prompted by my grown-up children’s questions, and my conviction that the lessons of my Nazi childhood must not be lost, especially in this time of fear and of peril for the American Democracy." (43)

Primary Sources

(1) Irmgard Paul, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005)

After years of being made to feel like beggars and scum, they lent an eager ear to the man who told them that Germany was not only a worthy nation but a superior one. Anyone who promised economic stability would capture the nation's mind and soul as well. Of all the Weimar politicians, only Hitler understood fully that playing up patriotism and making false promises to every interest group would garner a following. And most important, perhaps, he realized that instilling fear of a vaguely defined enemy - the conspirators of world Jewry - would bring a suspicious and traumatized people, including my own mother and father, to his side...

I heard no tales of Kristallnacht that so infamously and unashamedly revealed the intent to dehumanize Jews. These ominous portents on the seemingly bright horizon were smoothed over by the Nazi leaderships' frenzied moral outrage and denunciation of whole segments of the population. Silently my father and mother held on to their delusion that indeed a happy future lay ahead in our cheery home with Hitler's red wax portrait watching over us.

(2) Irmgard Paul, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005)

The morning after we got the death notice, my teacher, Fräulein Stöhr, a fanatical Nazi, ordered me to stand up in front of the class and tell everyone how proud I was that my father had given his life for the Führer. I stood before those hundred children, my face burning, my hurt heart thumping. I clenched my fists and swallowed hard, determined not to cry or otherwise show anyone how I felt. I forced myself to drain all emotion from my voice, even forcing my mouth into a grin, and said, Yes, we heard yesterday that my father died in France for the Führer. Heil Hitler. My face was flushed, but I made sure to walk calmly back to my seat.

(3) Irmgard Paul, On Hitler's Mountain: My Nazi Childhood (2005)

School was the serious side of life, never meant to make a child happy. From the day mother delivered me into Fräulein Stöhr's clutches it was obvious that this woman was a fanatical Nazi. A true believer. Surely she had become a teacher not because she had an affinity for children but because she wanted to tyrannize them. The Nazi doctrines designed to raise citizens wholly obedient to the Führer's bidding captivated and excited her. I began first grade at Easter 1940, but since Hitler changed the beginning of the school year to the fall shortly afterward, I am not quite sure whether my first year was very short or very long. At any rate, the war had already eaten into resources and materials, as well as the supply of male teachers, most of whom were drafted. As a result, Fräulein Stöhr got to sink her fangs into one hundred children belonging to three different grades. We were huddled together in her stark, whitewashed classroom learning the basics by rote plus a bit of local history, needlework for the girls, and geography.The curriculum did not include anything like "political education", but Fräulein Stöhr knew how to use occasions like my father's death, Hitler's birthday, good or bad news from the front, or the visit of a prominent local Nazi to indoctrinate us.... Hitler found the brown eyes and dark hair dominant among the valley's people not to his liking, suspecting undesirable Italian or even Slavic influences, and accordingly, Fräulein Stöhr seemed to prefer the Nordic-looking children...

Prussian obedience, order, and discipline as well as blind submission to Nazi ideology were Fräulein Stöhr's undisputed forte. In these efforts she was aided by two canes cut from a filbert bush, one thin and one thick. She used them for slight infractions.... Over the course of two years she used her filbert canes on my hands at least four times, three times for whispering answers to kids she had called on. Each time I had to leave my crowded bench and walk, embarrassed and infuriated, to the front of the classroom and onto the podium to receive a couple of stinging lashes on my outstretched hand.

(4) Irmgard Paul, interview with Harper Collins (2005)

Question: The words: "I felt thoroughly sick of these conflicts forced upon me by adults" leapt off the page. How do you think adults use children to enhance their own sense of power? Should adults take more care to expose children to conflicting ideas and points of view to help them form sound, personal opinions?

Answer: Politicians, including Hitler, thrive on being portrayed with smiling, happy children providing evidence that the future of the country is in caring, fatherly hands. I think that the worst misuse of children is to turn them into spies, informers, and even soldiers. In free societies, teachers and especially parents have the obligation to prevent politicians from establishing policies that endanger their children’s future freedoms and well-being. Most of all, they have the responsibility to expose children to diverging views, to expect tolerance, and to encourage them to question things and to stand up for their views. Parents should never cede this responsibility to ideologues who may use propaganda machines as good as those of Goebbels.

Question: Do you see similarities between present day societies that indoctrinate children with hatred and intolerance and those in your childhood in the Third Reich?

Answer: Most political regimes look to the nation’s youth to assure their own future and the next generation of devoted followers. Putting children in uniforms and making them feel part of a larger cause are well-tested tricks of authoritarian regimes. One-sided pressure and the teaching of superiority and intolerance often paired with intimidation are almost impossible for a child to fight off. Poverty and hopelessness provide particularly fertile ground for hatred to take root as we have seen in Germany in the twenties. But even in democratic countries improving children’s lives should be a priority on a nation’s agenda.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)