George May

George Ernest May, the younger son of William C. May, grocer and wine merchant, and his wife, Julia Ann Mole May, was born in Cheshunt on 20th June 1871. At the age of sixteen he left Cranleigh School and joined the Prudential Assurance Company. Established in 1848 the Prudential had pioneered the development of industrial life assurance based on the collection of small premiums from those of modest means. (1)

Initially he entered the cashier's department of the Prudential as a junior clerk but was later transferred to the investment department in 1902. The following year he married Lily Julia Strauss. They had two sons and a daughter. At the Prudential, May rose to become controller in 1910 and company secretary in 1915. At this time the Prudential's assets amounted to some £95 million. (2)

During the First World War George May was recruited by Reginald McKenna to deal with the Treasury American dollar securities committee. May proposed informally to his directors that the Prudential should offer to sell its American securities (subsequently valued at £8,407,650) to the government to provide dollars. According to William Maxwell Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) this enabled McKenna the assert his power over Walter Cunliffe, the Governor of the Bank of England. (3)

May made similar arrangements with other British investment institutions. Alongside this, his administrative talents were deployed as deputy quartermaster-general of the Navy and Army canteens board. He was responsible for the entire forces' catering arrangements. His success in these activities built good relations across the City and in government. He was awarded a KBE for war service in 1918. The following year he lost the use of one eye and suffered periods of blindness. (4)

The Great Depression

In June 1930, unemployment in Britain was 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. Ramsay MacDonald, the Prime Minister, responded to the crisis by asking John Maynard Keynes to become a chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to "advise His Majesty's Government in economic matters". Members of the committee included J. A. Hobson, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Hugh Macmillan, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. However, Keynes was disappointed by MacDonald's reaction to his advice: "Politicians rarely look to economists to tell them what to do: mainly to give them arguments for doing things they want to do, or for not doing things they don't want to do." (5)

George Douglas Cole later recalled: "Philip Snowden held a strong position in the Party as its one recognised financial expert... MacDonald nor most of the other members of the Cabinet had any understanding of finance, or even thought they had... The Economic Advisory Council, of which I was a member, discussed the situation again and again; and some of us, including Keynes, tried to get MacDonald to understand the sheer necessity of adopting some definite policy for stopping the rot. Snowden was inflexible; and MacDonald could not make up his mind, with the consequence that Great Britain drifted steadily towards a disaster." (6)

Philip Snowden, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, wrote in his notebook on 14th August that "the trade of the world has come near to collapse and nothing we can do will stop the increase in unemployment." He was growing increasingly concerned about the impact of the increase in public-spending. At a cabinet meeting in January 1931, he estimated that the budget deficit for 1930-31 would be £40 million. Snowden argued that it might be necessary to cut unemployment benefit. Margaret Bondfield looked into this suggestion and claimed that the government could save £6 million a year if they cut benefit rates by 2s. a week and to restrict the benefit rights of married women, seasonal workers and short-time workers. (7)

The George May Committee

Unemployment continued to rise and the national benefit fund was now in deficit. Austen Morgan, has argued that when Ramsay MacDonald refused to become master of events, they began to take control of the Labour government: "With the unemployed the principal sufferers of the world recession, he allowed middle-class opinion to target unemployment benefit as a problem... With Snowden at the Treasury, it was only a matter of time before the economic issue was being defined as an unbalanced budget." (8)

In February 1931, on the advice of Philip Snowden, MacDonald asked George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. Other members of the committee included Arthur Pugh (trade unionist), Charles Latham (trade unionist), Patrick Ashley Cooper (Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company), Mark Webster Jenkinson (Vickers Armstrong Shipbuilders), William Plender (President of the Institute of Chartered Accountants) and Thomas Royden (Thomas Royden & Sons Shipping Company). (9)

A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out that four of the May Committee were leading capitalists, whereas only two represented the labour movement: "Snowden calculated that a fearsome report from this committee would terrify Labour into accepting economy, and the Conservatives into accepting increased taxation. Meanwhile he produced a stop-gap budget in April, intending to produce a second, more severe budget in the autumn." Snowden made speeches in favour of "national unity" hoping that he would get help from the other political parties to push through harsh measures. (10)

Snowden came increasing under attack from England's leading economists. John Maynard Keynes criticised Snowden's belief in free-trade and urged the introduction of an import tax in order that Britain might resume the vacant financial leadership of the world, which no one else had the experience or the public spirit to occupy. Keynes believed this measure would create a budget surplus. (11) Others questioned the wisdom of devoting £60m to paying off the national debt. (12)

On 14th July, the Economic Advisory Council published its report on the state of the economy. Chaired by Hugh Macmillan, committee members included John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole, Walter Citrine, Hubert Henderson, Walter Layton, William Weir and Andrew Rae Duncan. The report drew attention to Britain's balance of payments. "The export of manufactured goods had not paid for the import of food and raw materials for over a hundred years but this had been made up by so-called 'invisible' earnings, such as banking, shipping and the interest on foreign income. These had declined with the recession. Crude estimates a new economic indicator - suggested that Britain was about enter into a balance of payments deficit... By way of solution, they proposed a revenue tariff." (13)

In July, 1931, the George May Committee produced (the two trade unionists refused to sign the document) its report that presented a picture of Great Britain on the verge of financial disaster. It proposed cutting £96,000,000 off the national expenditure. Of this total £66,500,000 was to be saved by cutting unemployment benefits by 20 per cent and imposing a means test on applicants for transitional benefit. Another £13,000,000 was to be saved by cutting teachers' salaries and grants in aid of them, another £3,500,000 by cutting service and police pay, another £8,000,000 by reducing public works expenditure for the maintenance of employment. "Apart from the direct effects of these proposed cuts, they would of course have given the signal for a general campaign to reduce wages; and this was doubtless a part of the Committee's intention." (14)

The five rich men on the committee recommended, not surprisingly, that only £24 million of this deficit should be met by increased taxation. As David W. Howell has pointed out: "A committee majority of actuaries, accountants, and bankers produced a report urging drastic economies; Latham and Pugh wrote a minority report that largely reflected the thinking of the TUC and its research department. Although they accepted the majority's contentious estimate of the budget deficit as £120 million and endorsed some economies, they considered the underlying economic difficulties not to be the result of excessive public expenditure, but of post-war deflation, the return to the gold standard, and the fall in world prices. An equitable solution should include taxation of holders of fixed-interest securities who had benefited from the fall in prices." (15)

William Ashworth, the author of An Economic History of England 1870-1939 (1960) has argued: "The report presented an overdrawn picture of the existing financial position; its diagnosis of the causes underlying it was inaccurate; and many of its proposals (including the biggest of them) were not only harsh but were likely to make the economic situation worse, not better." (16) Keynes reacted with great anger as it was the complete opposite of what he had been telling the government to do and called the May Report "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read". (17)

The May Report had been intended to be used as a weapon to use against those Labour MPs calling for increased public expenditure. What it did in fact was to create abroad a belief in the insolvency of Britain and in the insecurity of the British currency, and thus to start a run on sterling, vast amounts of which were held by foreigners who had exchanged their own currencies for it in the belief that it was "as good as gold". This foreign-owned sterling was now exchanged into gold or dollars and soon began to threaten the stability of the pound. (18)

The Labour government officially rejected the report because MacDonald and Snowden could not persuade their Cabinet colleagues to accept May's recommendations. MacDonald and Snowden now formed a small committee, made up of themselves and Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham, three people they thought they could persuade to accept public spending cuts. Their report was published on 31st July, the last day of parliament sitting. It was a bland document that made no statement on May's recommendations. (19)

On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, arguing that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the gold standard and devalue sterling. (20)

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the Cabinet on 20th August. It included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Most members of the Cabinet rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made. Clement Attlee, who was a supporter of Keynes, condemned Snowden for his "misplaced fidelity to laissez-faire economics". (21)

Arthur Henderson argued that rather do what the bankers wanted, Labour should had over responsibility to the Conservatives and Liberals and leave office as a united party. The following day MacDonald and Snowden had a private meeting with Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare, Herbert Samuel and Donald MacLean to discuss the plans to cut government expenditure. Chamberlain argued against the increase in taxation and called for further cuts in unemployment benefit. MacDonald also had meetings with trade union leaders, including Walter Citrine and Ernest Bevin. They made it clear they would resist any attempts to put "new burdens on the unemployed". Sidney Webb later told his wife Beatrice Webb that the trade union leaders were "pigs" as they "won't agree to any cuts of unemployment insurance benefits or salaries or wages". (22)

At another meeting on 23rd August, 1931, nine members (Arthur Henderson, George Lansbury, John R. Clynes, William Graham, Albert Alexander, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Johnson, William Adamson and Christopher Addison) of the Cabinet stated that they would resign rather than accept the unemployment cuts. A. J. P. Taylor has argued: "The other eleven were presumably ready to go along with MacDonald. Six of these had a middle-class or upper-class background; of the minority only one (Addison)... Clearly the government could not go on. Nine members were too many to lose." (23)

That night MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. His son, Malcolm MacDonald, wrote in his diary: "The King has implored the J.R.M. to form a National Government. Baldwin and Samuel are both willing to serve under him. This Government would last about five weeks, to tide over the crisis. It would be the end, in his own opinion, of J.R.M.'s political career. (Though personally I think he would come back after two or three years, though never again to the Premiership. This is an awful decision for the P.M. to make. To break so with the Labour Party would be painful in the extreme. Yet J.R.M. knows what the country needs and wants in this crisis, and it is a question whether it is not his duty to form a Government representative of all three parties to tide over a few weeks, till the danger of financial crash is past - and damn the consequences to himself after that." (24)

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel, MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself." (25)

The National Government

On 24th August 1931 King George V had a meeting with the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal parties. Herbert Samuel later recorded that he told the king that MacDonald should be maintained in office "in view of the fact that the necessary economies would prove most unpalatable to the working class". He added that MacDonald was "the ruling class's ideal candidate for imposing a balanced budget at the expense of the working class." (26)

Later that day MacDonald returned to the palace and had another meeting with the King. MacDonald told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to continue to serve as Prime Minister. George V congratulated all three men "for ensuring that the country would not be left governless." (27)

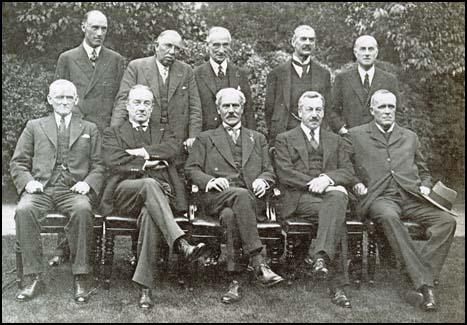

Lord Reading, Neville Chamberlain, Samuel Hoare. Seated, left to right: Philip Snowden,

Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, Herbert Samuel and John Sankey.

Ramsay MacDonald was only able to persuade three other members of the Labour Party to serve in the National Government: Philip Snowden (Chancellor of the Exchequer) Jimmy Thomas (Colonial Secretary) and John Sankey (Lord Chancellor). The Conservatives had four places and the Liberals two: Stanley Baldwin (Lord President), Samuel Hoare (Secretary for India), Neville Chamberlain (Minister of Health), Herbert Samuel (Home Secretary), Lord Reading (Foreign Secretary) and Philip Cunliffe-Lister (President of the Board of Trade).

George May now took an active role in politics and helped draft a manifesto calling for import tariffs. The Import Duties Act (1932) provided for an import duties advisory committee to advise the Treasury on additional duties for particular goods when in the national interest. May was appointed as its chairman. May also advised MacDonald and the National Government on industrial policy. (28)

House of Lords

in June 1935, George May was granted the title Baron May and became active in the House of Lords. During this time Sir George Barstow, a close friend, described May as being "tall, slim, and erect, with an air of aloof distinction, emphasized in later life by his poor eyesight and the wearing of a monocle. He was a great believer in personal contact rather than the written word, and his charm, his remarkable memory, his ability to concentrate on essentials and to pursue his objectives with single minded purpose - these qualities, coupled with his swift and shrewd judgement of men and situations, admirably fitted him for this method of conducting affairs." (29)

Herbert Hutchinson added: "George May was a dapper, white haired man of cool and easy approach… He did not involve himself unduly in detail, but he had a great shrewdness, sound judgement, and readiness to take a risk. His ability to express himself at logical length either in speech or writing was limited, but his mind was one of those that leap to a sound conclusion more quickly than logic carries others." (30)

George May, first Baron May, died in London on 10th April, 1946.

Secondary Sources

(1) Herbert Hutchinson, Tariff-making and Industrial Reconstruction (1965)

George May was a dapper, white haired man of cool and easy approach … He did not involve himself unduly in detail, but he had a great shrewdness, sound judgement, and readiness to take a risk. His ability to express himself at logical length either in speech or writing was limited, but his mind was one of those that leap to a sound conclusion more quickly than logic carries others.

(2) Austen Morgan, J. Ramsay MacDonald (1987)

On 14 July, the Macmillan Committee on finance and industry reported the results of its deliberations. It did not argue for the abandonment of the gold standard. Keynes believed that confidence in the albeit overvalued pound would be shaken in present circumstances if it was not redeemable at par in gold. The committee, however, did come out in favour of a managed currency. It saw a rise in the price level halting the spiral of deflation but this was very much a recommendation for the future.

The Macmillan Report did, however, draw attention to Britain's balance of payments. The export of manufactured goods had not paid for the import of food and raw materials for over a hundred years but this had been made up by so-called "invisible" earnings, such as banking, shipping and the interest on foreign income. These had declined with the recession. Crude estimates a new economic indicator - suggested that Britain was about enter into a balance of payments deficit. It was this which alarmed Keynes and Bevin in 1931. By way of solution, they proposed a revenue tariff.

This was eclipsed on 30 July, when the report of the May committee went to cabinet as MPs were preparing to adjourn for the summer. It predicted an immediate deficit on the budget of 120 million pounds. The committee had comprised five rich men and two trade unionists. Their report was a thoroughly ideological document, from which the supposed representatives of Labour gently dissented. It proposed that the budget should be balanced with tax increases of twenty-four million and cuts in expenditure of ninety-six million.

The May Report reaffirmed the idea that an unbalanced budget was a problem. It went on to make a number of unwarranted assumptions. Firstly, the annual payment to the sinking fund of fifty million was considered untouchable. Secondly, reductions in national debt payments - which were to be implemented in 1932 - were not even considered. Thirdly, the increasing number of old-age pensioners was not offset against the declining number of school children. Fourthly, the figure for increased taxation was, of course, arbitrary, as was the proposed level of expenditure. Fifthly, the deficit on the insurance fund had become notorious and May charged this and the cost of "transitional" benefits to the Exchequer. National insurance was made to bear most of the cuts. The proposed reduction of twenty per cent in benefits was larger than the fall in prices but less than that recommended by the royal commission. In either case, the unemployed were to carry the burden of whatever financial crisis, in spite of the fact that they were already the victims of a Capitalist breakdown.

The Treasury wanted the May proposals for an autumn budget. A cabinet committee, comprising MacDonald, Snowden, Henderson, Thomas and Graham, was established to consider the May report. It was published on 31 July, the last day of parliament's sitting. The government made no statement on May's recommendations and the cabinet committee was not due to meet until 25 August.

(3) G. D. H. Cole, A History of the Labour Party from 1914 (1948)

The mounting cost of unemployment benefits in face of falling revenue due to the depression of industry and trade was, however, only one factor in the situation. At any rate by the beginning of 1931 Philip Snowden had made up his own mind that the " state of the nation " called for a policy of drastic retrenchment in public expenditure, which could in practice be brought about only by cuts in the social services. Snowden was determined to balance his Budget for 1931-2, and was also determined not to impose any additional taxes on trade or industry, wishing rather to reduce taxes which he regarded as falling on the cost of production, and therefore as hindering overseas trade and tending to reduce employment. If the Budget was to be balanced without additional taxation, the only course was to reduce expenditure heavily-or rather, this was the only course on the assumption that the Sinking Fund for the repayment of the National Debt must be left intact. Snowden insisted that the Sinking Fund must be kept up, partly because he was looking for a chance to convert a large mass of maturing debt to a lower rate of interest, but also partly because he regarded it as almost inviolable on grounds of financial integrity, and believed that any suspension of it would shake international confidence in Great Britain's economic position. The problem, as Snowden saw it, was to persuade the Labour Party to accept a policy of retrenchment at the expense of the social services and, above all, of the unemployed, and at the same time to keep up debt repayments and to refrain from further taxes falling on profits.

Snowden was, of course, well aware that to present any such set of proposals to the Labour Party would be to invite overwhelming defeat. He therefore took a devious course towards what he had in mind to do. In February, 1931, he took advantage of a Tory motion and a Liberal amendment both calling for reductions in national expenditure to make a vaguely alarmist speech, without going into details or putting forward any positive proposals. The Liberal amendment proposed the appointment of "a small and independent Committee to make representations to Mr. Chancellor of the Exchequer for effecting forthwith all practical and legitimate reductions in the national expenditure consistent with the efficiency of the services." To this amendment Snowden persuaded the Government to give its support; and when it was carried he proceeded to appoint the notorious " May Committee," under the chairmanship of Sir George May, the retiring Chairman of the Prudential Insurance Company. There were only two Labour representatives on the Committee, to which Snowden evidently looked for a swingeing Report that would compel his own Party to yield.

Having done this, Snowden proceeded to introduce a very mild Budget, which, he was well aware, would leave the deficit uncovered and would make no contribution towards a solution of the financial crisis. He as good as admits this in his Autobiography, and as good as says that his idea was to get the May Committee's Report first, and then introduce a second " Economy " Budget in the autumn. In fact, he was planning to force his colleagues' hands, with the aid of the reactionaries whom he had appointed to sound the alarm.

Snowden got what he wanted. In July, 1931, the May Committee produced (with the two Labour representatives dissenting) its intentionally sensational Report. By adding the deficit on the Unemployment Insurance Fund to the deficit on the Budget proper, by making the gloomiest possible forecasts of future deficits, and by treating the sums to be applied to repayment of debt as necessary parts of the national expenditure, the May Committee managed to present a picture of Great Britain as on the verge of sheer financial disaster. On this basis it went on to propose cutting £96,000,000 off the national expenditure. Of this total £66,500,000 was to be "saved" by cutting unemployment benefits by 20 per cent, by raising contributions to the Fund, and by imposing a means test on applicants for transitional benefit. Another £13,000,000 was to be "saved" by cutting teachers' salaries and grants in aid of them, another £3,500,000 by cutting service and police pay, another £8,000,000 by reducing public works expenditure for the maintenance of employment. Apart from the direct effects of these proposed cuts, they would of course have given the signal for a general campaign to reduce wages; and this was doubtless a part of the Committee's intention.

Immediately upon the receipt of the May Report, the Labour Cabinet set up an "Economy Committee," consisting of MacDonald, Snowden, Henderson, Thomas and William Graham; and Snowden began through this body to press his policy hard. The Labour Government had already involved itself in constant consultation with the leading members of the Liberal and Tory Parties; and from this time on there was also constant consultation between Snowden and MacDonald and the bankers - not only the Bank of England but also the representatives of the "City" and of the joint stock banks. The May Report had been intended for home consumption, as a weapon against the main body of the Labour M.P.s and against Labour opinion in the country. What it did in fact was to create abroad a belief in the insolvency of Great Britain and in the insecurity of the British currency, and thus to start a run on sterling, vast amounts of which were held by foreigners who had exchanged their own currencies for it in the belief that it was "as good as gold." This foreign-owned sterling now began to be withdrawn at an increasing pace, and exchanged into gold or dollars; and the withdrawals involved a drain on the exchanges, and soon began to threaten the stability of the pound. The simple immediate counter to this danger would have been to stop the export of gold, and to go off the gold standard. But this Snowden was not prepared even to consider; and the bankers agreed with him in regarding the gold standard as the ark of the financial covenant. I, for one, took a different view, and urged the Government, both in private and in public, to control the exchanges at once, instead of waiting to be driven off gold by forces too strong to be resisted. No such solution was considered at all : instead the Bank of England took the futile step of borrowing £50,000,000 from the Bank of France and the New York Federal Reserve Bank in the hope of checking the drain. The May Report, however, had done its work all too well. The drain continued; and the £50,000,000 was soon drawn away.