Field Punishment Number One

Flogging was finally abolished in the British Army in 1881. The usual sentences for the offences of desertion and sleeping on guard duty varied between four months' imprisonment with hard labour and ten years' penal servitude. During wartime, soldiers could be executed for these offences.

When flogging came to an end in 1881 a new way of dealing with soldiers found guilty of minor offences such as drunkenness was also introduced. This was called Field Punishment Number One and involved the offender being attached to a fixed object for up to two hours a day and for a period up to three months. During the First World War, these men were sometimes put in a place within range of enemy shell-fire.

Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier justified this treatment in his book, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930): "My duty was to teach them the Regulations and the Army Act where they could see the penalties, and to help them to overcome the difficulties which impel to desertion, cowardice and such - like offences which, in their case, if indulged in, lead to trouble and even death by shooting at the hands of comrades... Fear is no more a crime in war than in peace. Inability to control or smother fear is an unpardonable and dangerous crime in war and, as it is contagious, must be treated like any other disease in peace time - abolished I would remind the advocates of the abolition of the death sentence in war that to catch ann infectious disease in peace time is no crime; but to foster its spread, by non-notification is an offence against society which is rightly punished."

Private Frank Bastable was one of those who experienced it on the Western Front: "When on parade for rifle inspection, after opening the bolts and closing them again the second time as it did not suit the officer the first time, I accidentally let off a round. I had to go before the CO and got No. 1 Field Punishment. I was tied up against a wagon by ankles and wrists for two hours a day, 1 hour in the morning and 1 in the afternoon in the middle of winter and under shellfire."

George Coppard was totally opposed to this form of punishment: "One fine evening two military policemen appeared with a handcuffed prisoner, and, in full view of the crowd and villagers, tied him to the wheel of a limber, cruciform fashion. The poor devil, a British Tommy, was undergoing Field Punishment Number One, and this public exposure was part of the punishment. There was a dramatic silence as every eye watched the man being fastened to the wheel, and some jeering started. Lashing men to a wheel in public was one of the most disgraceful things in the war."

Junior officers such as Robert Graves also objected to treating soldiers in this way. In his autobiography, Goodbye to All That (1929) he wrote about how his servant, Private Fahy (Tottie) suffered Field Punishment Number One: "The next morning I was surprised and annoyed to find my buttons unpolished and only cold water for shaving; it made me late for breakfast. I could get no news of Tottie, but on my way to rifle inspection at nine o'clock at the company billet, noticed Field Punishment No. 1 being carried out in a comer of the farmyard. Tottie had just been awarded twenty-eight days of it for 'drunkenness in the field', and stood spread-eagled to the wheel of a company limber, tied by the ankles and wrists in the form of an X. He was obliged to stay in this position - Crucifixion they called it - for several hours every day so long as the battalion remained in billets, and then again after the next spell of trenches. I shall never forget the look that my quiet, respectful, devoted Tottie gave me. He wanted to tell me that he regretted having let me down, and his immediate reaction was an attempt to salute. I could see him vainly trying to lift his hand to his forehead, and bring his heels together."

On 29th October, 1916, the Illustrated Sunday Herald carried an article on punishment in the British Army written by social reformer, Robert Blachford. He began his article by quoting a letter that he had received describing the punishment of half-a-dozen soldiers from Liverpool who had lost their gas helmets on a march: "They were tied by the neck, waist, hands and feet to wheels for one hour." The correspondent claimed that one of the men had died during the punishment. Blachford described this as a "Hun-like torture" and should be brought to an end straight away.

As a result of the article questions about Field Punishment Number One were asked in the House of Commons. Government officials asked Sir Douglas Haig about this form of punishment. As Clive Emsley has pointed out: "Senior generals were consulted and most insisted that the punishment was necessary. Sir Douglas Haig, for example, thought that removing men from the Western Front to prison would provide a wrong signal and allow men to shirk their dangerous duties. He reiterated the belief that the stigma provided by the punishment was good both for the offender and as a deterrent to others." Haig went onto argue that he feared that abolition would have disastrous consequences and would mean that "a far larger percentage of those men whose moral fibre requires bracing by the daily fear of adequate punishment would give way at moments of supreme stress, and that recourse to the death penalty would have to become more frequent."

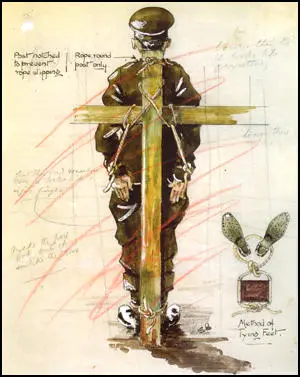

In January 1917 the War Office produced a watercolour sketch of what Field Punishment Number One should look like. Instructions were given that the ropes should not be too tight. The rope at the top of the post was to be lowered otherwise "it looks like garrotting". Officers were also told "make the post look entirely unlike the Cross". The instructions stated specifically that a man's feet were not to be tied more than 12 inches apart and that he must be able to move them three inches and if a man's arms and wrists were tied; there was to be at least six inches' play between them. It was also stated that the punishment should only be awarded for offences of "a disgraceful or insubordinate nature or for drunkenness".

George Coppard, the author of With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969), explained that the punishment was less severe after the War Office sent out instructions to their officers: "I believe that an important modification of the death sentence also took place in 1917. It appeared that the military authorities were compelled to take heed of the clamour against the death sentences imposed by courts martial. There had been too many of them. As a result, a man who would otherwise have been executed was instead compelled to take part in the fore-front of the first available raid or assault on the enemy. He was purposely placed in the first wave to cross No Man's Land and it was left to the Almighty to decide his fate. This was the situation as we Tommies understood it, but nothing official reached our ears. Let the War Office dig out its musty files and tell us how many men were treated in this way, and how many survived the cruel sentences. Shylock, in demanding his pound of flesh, had got nothing on the military bigwigs in 1917."

Primary Sources

(1) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

One fine evening two military policemen appeared with a handcuffed prisoner, and, in full view of the crowd and villagers, tied him to the wheel of a limber, cruciform fashion. The poor devil, a British Tommy, was undergoing Field Punishment Number One, and this public exposure was part of the punishment. There was a dramatic silence as every eye watched the man being fastened to the wheel, and some jeering started. Lashing men to a wheel in public was one of the most disgraceful things in the war. Troops resented these exhibitions, but they continued until 1917, when the War Minister put a stop to them, following protests in Parliament.

I believe that an important modification of the death sentence also took place in 1917. It appeared that the military authorities were compelled to take heed of the clamour against the death sentences imposed by courts martial. There had been too many of them. As a result, a man who would otherwise have been executed was instead compelled to take part in the fore-front of the first available raid or assault on the enemy. He was purposely placed in the first wave to cross No Man's Land and it was left to the Almighty to decide his fate. This was the situation as we Tommies understood it, but nothing official reached our ears. Let the War Office dig out its musty files and tell us how many men were treated in this way, and how many survived the cruel sentences. Shylock, in demanding his pound of flesh, had got nothing on the military bigwigs in 1917.

(2) Private Frank Bastable, Royal West Kent Regiment, interviewed in 1978.

When on parade for rifle inspection, after opening the bolts and closing them again the second time as it did not suit the officer the first time, I accidentally let off a round. I had to go before the CO and got No. 1 Field Punishment. I was tied up against a wagon by ankles and wrists for two hours a day, 1 hour in the morning and 1 in the afternoon in the middle of winter and under shellfire.

(3) Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That (1929)

When I left the Second Battalion, the adjutant let me take my admirable servant. Private Fahy (known as 'Tottie Fay', after the actress), with me. Tottie, a reservist from Birmingham, had been called up when war broke out, and fought with the Second Battalion ever since. By trade a silversmith, he had recently gone on leave, and brought me back a gift cigarette-case, all his own work, engraved with my name. On arrival at the First Battalion, however, he met one Sergeant Dickens. They had been boozing chums in India seven or eight years ago, and joyfully celebrated the reunion.

The next morning I was surprised and annoyed to find my buttons unpolished and only cold water for shaving; it made me late for breakfast. I could get no news of Tottie, but on my way to rifle inspection at nine o'clock at the company billet, noticed Field Punishment No. 1 being carried out in a comer of the farmyard. Tottie had just been awarded twenty-eight days of it for 'drunkenness in the field', and stood spread-eagled to the wheel of a company limber, tied by the ankles and wrists in the form of an X. He was obliged to stay in this position - 'Crucifixion' they called it - for several hours every day so long as the battalion remained in billets, and then again after the next spell of trenches. I shall never forget the look that my quiet, respectful, devoted Tottie gave me. He wanted to tell me that he regretted having let me down, and his immediate reaction was an attempt to salute. I could see him vainly trying to lift his hand to his forehead, and bring his heels together.

(4) John Hughes-Wilson, Blindfold and Alone: British Military Executions (2001)

If a man was sentenced while on active service (for example, if he found himself willingly or unwillingly at the Front in France) he became liable to a range of punishments, including Field Punishment Number One, popularly known as "crucifixion". Briefly, the offender was kept in irons and attached to a "fixed object" for up to two hours a day and for a period up to three months and the fixed object was not specified. The procedure was not standardised, and allegations arose that men were being attached to the wheels of guns in emplacements that were within range of enemy shell-fire.

(5) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

The question of the temperamental fitness of soldiers to be ordered into the line and shot if they fail to stay there was one which, of course, I could not discuss with my own officers in the training stage. My duty was to teach them the Regulations and the Army Act where they could see the penalties, and to help them to overcome the difficulties which impel to desertion, cowardice and such - like offences which, in their case, if indulged in, lead to trouble and even death by shooting at the hands of comrades. The question of ability to "stick it" or to do the right thing in the right way, in action, is largely one of morale; but the fact cannot be overlooked that fear of the consequences undoubtedly plays an important part in the reasoning powers of men distracted by fear, cold, hunger, thirst or complete loss of morale and staying power. I should be very sorry to command the finest army in the world on active service without the power behind me which the fear of execution brings. Those who wish to abolish the death sentence for cowardice and desertion in war should aim at a higher mark and strive to abolish war itself. The one is the product of the other. Some people, particularly Labour Cabinet ministers and leaders seem to think that "fear" itself is a crime in war. Fear is no more a crime in war than in peace. Inability to control or smother fear is an unpardonable and dangerous crime in war and, as it is contagious, must be treated like any other disease in peace time - abolished I would remind the advocates of the abolition of the death sentence in war that to catch ann infectious disease in peace time is no crime; but to foster its spread, by non-notification is an offence against society which is rightly punished.